Syria Podcast, Part 2

A poster showing Syrian president Bashar al-Assad hangs on a wall in a damaged room inside National Hospital after explosions hit the Syrian city of Jableh, May 23, 2016. Omar Sanadiki/Reuters

Nader Hashemi is an associate professor of Middle East and Islamic politics and director of the Center for Middle East Studies in the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. On Twitter: @naderalihashemi.

Saved by Europe or Killed by Trump?

Shoot first, ask questions later. That was the decision made by Donald Trump last week when he chose to violate and withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal. To hear U.S. and European officials tell it, the Trump administration does not have a Plan B in place, and its attempts to construct one on the fly have been a mess. Moreover, not a single treaty ally supports Trump’s decision. At face value, this amounts to an extraordinary isolation of the United States. The reality, however, is more complicated. Precisely because these dynamics remain fluid, two key uncertainties remain in the global quest to keep the Iran deal alive: Europe’s ability to have an Iran policy independent of Washington; and the degree to which U.S.-EU policy divergence on Iran will damage transatlantic relations.

While Trump, Israel and Saudi Arabia have escalated their shared hostility toward Iran, Europe has consistently pushed for cooler heads to prevail. EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini said that the United States has no right to unilaterally terminate the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and British Prime Minister Theresa May issued a joint statement reaffirming their support for the agreement, describing it as “in our shared national security interest.” Macron went a step further, stating publicly what many European officials have told me privately: “The official line pursued by the United States, Israel and Saudi Arabia… is almost one that would lead us to war,” and this attempt to trigger military confrontation was “a deliberate strategy for some.” And this was all before Trump violated and withdrew from the JCPOA on May 8.

Since then, Trump has faced a barrage of verbal condemnation from America’s allies in Europe who remain verbally committed to the deal. Mogherini did not mince her words, saying “it seems that screaming, shouting, insulting, and bullying, systematically destroying and dismantling everything that is already in place, is the mood of our times…This impulse to destroy is not leading us anywhere good. It is not solving any or our problems.” Merkel said Trump’s decision “undermines trust in the international order,” and demonstrates that “it is no longer such that the United States simply protects us, but Europe must take destiny in its own hands.” Macron followed suit, emphasizing that it was a “pity” and a “mistake.” Merkel, Macron, and Theresa May issued a joint statement expressing “regret and concern” and urging the U.S. “to avoid taking action which obstructs its full implementation by all other parties to the deal.”

All of this begs the question: Can Europe go it alone? The short answer is: Yes, but it’s going to be a herculean task. After 15 months of Trump’s presidency, a variety of factors—from abandoning the Paris climate accords, to hedging on America’s NATO obligations, to violating and withdrawing from the JCPOA—have demonstrated to Europe a heightened degree of unreliability emanating from Washington. As a result, Europeans will likely be forced to continuously confront a set of decisions on previously shared policy approaches, including on Iran: Try to buffer and modestly move U.S. policy, or strike out on its own. European officials have privately acknowledged to me that this is a decision they may have to make ad infinitum, leading some to call for Europe to be more assertive in setting foreign policy according to its own interests rather than those of the United States. “Germany cannot afford to wait for decisions from Washington, or to merely react to them,” former German foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel stated matter-of-factly this past December before leaving his post. “We must lay out our own position and make clear to our allies where the limits of our solidarity are reached.”

One does not have to look far into Europe’s past to find an Iran policy independent of the U.S. From 1992 to 1997, the EU established a “Critical Dialogue” with Iran to address a variety of issues. From 1998 to 2002, the two parties established a “Comprehensive Dialogue” to deepen cooperation and work towards signing a trade and cooperation agreement. During Mohammad Khatami’s presidency (1997-2005), the European Union became Iran’s largest trading partner. In an interview with Iranian media, Federica Mogherini said: “We are the ones that used to be Iran’s first partner on the economic fields, on trade, investment, and we want to be back to that.”

The 1990s and early 2000s were a time when Europe not only had a different Iran policy, but also faced Dick Cheney-esque excoriations for doing so. “I can remember a conversation with Cheney when I was in Washington. I bumped into him at an embassy function, and he said to me, ‘the Iranians know what they have to do.’ That was America’s policy,” a former European ambassador to Iran explained to me. “In other words, surrender on all fronts. Change their policy on all fronts. That was the line then, and that is the line now, and Europe took a distinct stance then, and will continue to do so. I’m absolutely sure that [my] government will stay resolute behind an engagement policy.”

In all of my recent conversations with European officials, they felt their respective countries were pursuing their own policy, trying to maximize their leverage through the European Union, and use the EU as well as their own bilateral relationships in pursuit of objectives that differed from the U.S.—and they believe Europe should continue to do so during Trump’s presidency. To hear some European Union officials tell it, the future can be bright. “I definitely think as far as Europeans are concerned, we have our autonomous policy when it comes to Iran,” a senior EU official told me. “One of the great things that happened since the JCPOA was concluded is that the context of EU-Iran relations has been institutionalized. Iran is not seen as enemy anymore in the EU. It’s seen as sometimes adversarial. It’s definitely seen as a country with problems, but it also is seen as an opportunity.”

Moreover, the political changes that have taken place in Washington since Trump entered the White House have no parallel across the pond. Most European officials who helped negotiate and implement the JCPOA are still serving in their same professional capacities. Thus, it is beyond belief that they would be willing to kill an agreement which they: 1) Signed off on three years ago; and 2) Continue to assert is both working and in their shared interest. “Europe has a vested political and institutional interest in getting positive things done on Iran,” a senior EU official explained to me. “This is why we have such a lively traffic of officials traveling to Tehran, commissioners, working groups, task force, and Iranian officials coming to Brussels.” Indeed, the obstacles to more positive EU-Iran relations that existed a few years ago—both in Tehran and Brussels—have been significantly reduced precisely because securing and implementing the JCPOA has further incentivized breaking previous hostility.

To that end, the EU and Iran have exchanged numerous visits at the foreign minister level; President Rouhani made the first visit to Europe by an Iranian president in 16 years; and Mogherini has traveled to Iran with her colleagues on multiple occasions to solidify political and economic ties. The Europeans also established an Iran Task Force to boost cooperation, and EU-Iran trade increased by 94% in the first year of nuclear deal implementation.

“After the JCPOA,” a senior EU official told me, “the structure of incentives has changed completely. Therefore, I don’t think that Trump’s hostility will completely reverse EU policy.” Mogherini has been steadfast in this regard, repeatedly conveying this sentiment to her American interlocutors: “Europe feels a responsibility to engage with Iran [politically and economically]. I know this is not the U.S. policy, but it is the European policy and it will continue.”

Europeans, however, are not the only ones who believe the EU can and should keep the Iran deal alive regardless of Trump’s prerogatives. Many Americans share this view, emphasizing that Europe can have an Iran policy of its own. “Europe should be persuaded to keep the JCPOA with Iran, and we pay the price unfortunately,” a former senior U.S. official and ambassador to multiple countries told me. “I don’t like the price, but that price is less susceptible to producing conflict, but not susceptible at all to improving the deal.”

It has been clear from the outset of the Trump administration that America and Europe are not on the same wavelength. Trump abandoning the JCPOA is only the latest example—and it almost certainly will not be the last. Before Trump undercut Europeans on the JCPOA, the divide over Iran policy was painfully obvious. For example, on the same January 2018 day that the European Parliament hosted Alaeddin Boroujerdi—the chairman of the Iranian Parliament’s Foreign Affairs and National Security Committee—to discuss counter-terrorism, climate change, migration and trade, Vice President Mike Pence was in Israel telling Europeans they have to “decide whether they want to go forward with the United States or whether they want to stay in this deeply flawed deal with Iran.”

After Trump announced his withdrawal from the JCPOA, my iPhone was inundated with emails and text messages from current and former European officials expressing identical disbelief and displeasure: America is thus presenting the EU with another “you’re with us or against us” ultimatum, eerily reminiscent of George W. Bush in 2001. “Europeans are not at all allies in relation to Iran,” a former senior State Department official and U.S. ambassador explained to me. “They’re not at all on the same page, and they’re basically more annoyed by us, and our obsessions and fixations, than they are sympathetic to them.”

This sentiment becomes harder to deny with each passing day. While the Trump administration attempts to kill nuclear deals, clings to trade embargoes, and obsesses over adding new Iran sanctions to its books, Europe is seeking ways to capitalize on its long-standing interest in a more robust political and economic relationship with Tehran. The Iranians are keenly aware of this, and have doubled down on their efforts to build a successful relationship with Europe. Sustained progress on this front likely means that Trump’s effort to escalate hostilities—in scenarios not clearly provoked by Iran—will cause damage to transatlantic relations.

Even before Trump abandoned the JCPOA, Europe was already taking initial steps to assert its independence from the U.S. in unprecedented ways. 25 EU governments signed a defense pact—separate from NATO—to integrate their armed forces and lower their reliance on the United States. Giving the EU a military capability that it did not previously have reflects deep disillusionment with the United States, and to hear Western diplomats tell it, the Iran element in this decision-making should not be disregarded. After Trump slapped Europe in the face by violating and pulling out the JCPOA, European officials are openly discussing efforts to go their own way on Iran policy. French finance minister Bruno Le Marie has been the most outspoken thus far, stating that Europe must introduce a variety of countermeasures to U.S. sanctions on non-American firms doing business with Iran. It is ironic that Trump is getting a degree of the European self-reliance he claimed to want—because he has made Washington out to be unreliable and unpredictable.

Rebalancing in the U.S.-EU alliance does not change the relationship overnight, but it is a sign that a different context is emerging. This creates an opening—however small—for Iran to pursue. “If I were Zarif, trying to figure out where Iran should go, the last thing on Earth I’d worry about is trying anything with Washington or Riyadh at this time,” a former senior State Department official and U.S. ambassador told me. “I’d try to flank them by working with the Europeans.”

Europe has made clear that it will go to great lengths to save the Iran deal and avoid a cycle of escalation that could lead to war. European efforts to cooperate with Trump’s team on issues outside of the deal—ranging from Iran’s regional policies to its missile program—in return for full American compliance with its JCPOA commitments failed because Trump never wanted them to succeed. Europe now must conduct a delicate degree of balancing as Tehran continues to verifiably fulfill its end of the nuclear deal: To keep the agreement alive, Iran must receive concrete guarantees that it will receive the economic benefits that it was promised—which in turn requires Europe to enact measures of economic protection for its businesses from U.S. sanctions. And therein lies the rub. There are important caveats to any independent European policy on Iran.

For starters, the predominant school of thought in the Trump administration is wildly aggressive, seeking to strong-arm Europe into adopting Trump’s hardline position due to a belief that when forced to choose, the EU will side with Washington. This presents European governments with a significant dilemma: Any continued efforts to build a common approach with the U.S. will almost certainly fail, and a re-imposition of U.S. sanctions that were lifted as part of the JCPOA is around the corner. Indeed, European business efforts in Iran have already encountered a litany of problems. European subsidiaries to American firms are only capable of doing business with Tehran when it does not involve American citizens. There is no capacity in the international system to use U.S. dollars as a method of exchange in doing business with the Iranians. Major EU banks are refusing to work with Iran for fear of steep U.S. sanctions and corresponding fines. All of these problems stand to worsen while adding an unprecedented layer of complexity to the equation.

Thus, any independent EU policy on Iran will come down in large part to how much European governments can and will do to shield their businesses and financial institutions from the extraterritorial reach of the U.S. Congress and Treasury Department. In other words, Europe will have to, through its own legislative means, take additional steps to provide an unprecedented degree of shielding—literally creating political and economic infrastructure that does not currently exist. Anything short of that likely will result in European private sector institutions either avoiding Iran like the plague, or running afoul of unilateral American sanctions and losing business ties in the U.S. as well as billions of dollars in potential fines.

A key question, then, is whether EU governments can construct the necessary incentive structure to make their companies and banks comfortable with doing business in Iran. In my conversations with European companies, they are not happy with the conflict of law situations they are being thrown into by the United States. Thus, they are more comfortable with a separate EU policy that provides remedial support from their governments to make companies feel more secure. That is the crux of the matter: Europe is more than capable of having an independent Iran policy, but if they cannot keep their companies invested, either through giving them back-stopping or by threatening to punish the United States, that is where everything falls apart.

Even before Trump abandoned the JCPOA, Europe took some initial steps to that end. European governments have actively encouraged businesses to work with Tehran, and explained that doing so is legal and legitimate with the proper due diligence. While it is up to the companies to make the final decision on whether to pursue business in Iran, some have been willing to engage and governments have taken steps to facilitate the process. Austria’s Oberbank established a credit line worth up to 1 billion Euros with Iranian banks for Austrian companies to invest in Iran. France’s state investment bank has earmarked up to 500 million Euros a year into French businesses in Iran. It also agreed to offer Euro-denominated export guarantees to Iranian buyers of French goods and services. There is reportedly a pipeline of approximately 1.5 billion Euros in potential contracts from interested French exporters. Denmark’s Danske Bank established a 500 million Euro line of credit for deals involving some of Iran’s largest banks. And Denmark’s export credit rating agency guaranteed 100 percent of the financing of export deals—including against U.S. sanctions. The fact that medium-sized companies are pursuing business despite geopolitical instability and risk speaks to Europe’s clear interest in the Iranian market regardless of American preferences. Thus, there is a limit to how much damage Trump can do to European-Iranian relations without also doing serious damage to U.S.-European relations.

This is particularly true as the Trump administration prepares to unilaterally re-impose sanctions that were removed as part of the JCPOA, thereby trying to force Europe to choose: Cower to Trump or engage in a degree of brinkmanship with the United States. In the 1990s, Europe passed blocking legislation on U.S. secondary sanctions that were aimed at punishing companies that made energy investments in Iran. Rather than obey American diktats, European governments told their companies that they should not comply with U.S. sanctions, and the EU would protect them accordingly. Europe also told the Clinton administration that if it pulled the trigger on such sanctions, they would take America to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and engage in retaliatory sanctions. With the EU saying that it intends to press ahead in terms of making investments and engaging in trade with the Iranians, it is also clearly stating that it views the re-imposition of U.S. secondary sanctions as a capriciously hostile move—hence the aforementioned threats of its own regarding counter-measures.

Looking ahead, the key question is whether the Trump administration is willing to start a full-fledged trade war with Europe. And let’s be clear: It would be economically suicidal to do so. However, Trump does fancy himself an economic nationalist, so it is difficult to know for sure whether he might take the bait being served up by John Bolton and other ideologues on his national security team. If you assume a rational actor model, then America will blink. But with Trump, we may not be dealing with a rational actor. The degree to which Trump is actually prepared to punish a litany of European companies remains unknown. On the one hand, a self-described dealmaker who delivered a $1.5 trillion dollar tax cut for American businesses would seem among the least likely to damage U.S. business interests in Europe. On the other hand, this would not be the first instance in which Trump’s “America First” stance damaged both U.S. and EU interests.

U.S.-EU divergence on Iran policy is already clear, but the depth and scope of damage caused by this divergence going forward will depend entirely on Washington’s actions. In other words, it has become a sliding scale: The more hostile that Trump’s actions become, the more damage that will ensue—and the more likely Europe is to retaliate. The path ahead looks increasingly treacherous. Historically, since 1945, there have been significant occasions where Europe and the United States have diverged. The Vietnam War and 2003 Iraq War are prime examples. Politically, transatlantic relations suffered for a few years, and French fries were temporarily renamed “Freedom fries” in a rebuke to France, but no lasting damage was done and considerable overlap on policy matters remained.

This time, however, may be different. With Trump following through on his threat to leave the JCPOA and re-impose secondary sanctions, he is now trying to bully Europe into ignoring a UN Security Council resolution enshrining the nuclear deal—and instead surrendering to his bad faith desecration of international law. It is hard to see how such U.S.-EU policy divergence would avoid deeply damaging transatlantic ties. The concept of a rules-based world and effective multilateralism defines the foreign policy identity of the European Union. Trump’s deviation from that makes Europe less likely to count on the United States as much as it has in the past. As these things continue to happen, the transatlantic link is going to weaken. If Washington does not recognize that and take immediate steps to accommodate it, the United States is going to be in trouble.

As Europe seeks to diversify its geopolitical and economic relationships, the JCPOA provides unique opportunities to forge closer ties to Iran that can help prevent both military confrontation and the nuclear deal’s demise. The question is not whether the EU should pursue these objectives, but rather the best way to do so. Thus, Europeans should consider the following:

1) Open a EU Office in Tehran

To the credit of European diplomats, efforts to do so have commenced under the leadership of foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini, as well as with public support from the European Parliament—but have not yet yielded concrete results. While the EU has demonstrated its political will to achieve this objective, the best it has been able to do thus far is send diplomats to Tehran for weeks at a time every month. To that end, the merits of establishing a EU office are relatively straightforward. The symbolism is a clear sign of Europe’s commitment to deepening bilateral relations, and having people on the ground provides irreplaceable insight into what is going on inside Iran.

As the U.S. government’s 39-year absence of an embassy in Tehran repeatedly demonstrates, the quality of information gathering and country assessments cannot be replicated through intelligence or open-source information. Analyzing local developments requires a deep understanding and appreciation of the issues, culture, and pulse of Iran’s government and people. The personal contacts and interactions that a EU office will facilitate provide a more accurate assessment of local opportunities, risks and developments—all of which gives Europe a huge competitive advantage vis-à-vis Washington.

To hear senior Iranian officials tell it, the key obstacle to opening an EU office are hardliners who believe it will be used as an outpost to pressure Iran on human rights issues in ways that Europe does not when it comes to Saudi Arabia and other chronic human rights abusers in the region. This is not an insurmountable obstacle. Empowering like-minded Iranian counterparts to win this domestic debate can likely be achieved by applying standard human rights metrics and enforcement to all countries, and putting this in writing as official EU policy. Doing so will demonstrate to Iran that it is not treated any differently than Saudi Arabia, Israel, or the UAE.

2) Appoint a EU Senior Advisor for U.S.-Iran Conflict Prevention

The EU is already well positioned to assess Iran-related matters from a position of strength vis-à-vis a U.S. government that has no eyes and ears on the ground. Opening a EU office in Tehran will solidify its comparative advantage. In order to institutionalize and capitalize on this momentum, Europe should appoint a Senior Advisor for U.S.-Iran Conflict Prevention that reports to Mogherini—preferably selected from a country with a reputation for peace building, such as Sweden. Based out of the EU’s Tehran office, the Senior Advisor should regularly travel to Washington for consultations, and publish quarterly reports that document provocative actions taken by both sides and the necessary steps to reduce tensions.

By creating a senior European official whose mandate is preventing U.S.-Iran conflict, Europe will send a powerful message to both capitals. The former will see an EU that seeks to create stronger ties to Iran by playing the role of balancer rather than taking sides—thereby creating goodwill and loyalty amongst Iran’s government and people. The latter will see an EU that refuses to be strong-armed into adopting hostile U.S. policies that contradict European political, economic, and security interests—thereby signaling to Washington that it risks going it alone if diplomacy continues to be abandoned and a march to war commences.

3) Establish a EU-Iran Strategic Partnership

With a Tehran office and conflict prevention envoy locked in, Europe will have the building blocks in place to fast-track negotiations with Iran on a strategic partnership, using similar agreements with India, Brazil, China, and seven other nations as a model. Negotiations over a comprehensive political, trade, and security agreement will confirm the EU’s willingness to deepen and create a stronger framework for cooperation with Iran. Formalizing its acknowledgement of Tehran’s role as a regional power pivotal for resolving security challenges will help safeguard core EU interests and objectives.

While Europe’s strategic partnerships are underpinned by different political and legal frameworks, the metric applied to Iran should be as similar as possible to those already on the books. Creating such harmonization will demonstrate to Iran that its goodwill will be reciprocated, which in turn rewards Europe’s devotion of negotiating resources and energy by giving it a greater global sway as Washington’s interests vis-à-vis Tehran diverge. The economic aspect of a strategic partnership with Iran will boost EU competitiveness in a globalized economy as well as spread its established norms and standards. The political and security aspects will enhance cooperation on a number of key issues, including but not limited to: counter-terrorism, cybersecurity, non-proliferation, maritime security, climate change, development, and avoiding war—all of which empowers Europe as a global security guarantor at a time when Trump’s America retrenches.

4) Update and Reinstate Blocking Regulations

As Congress continues to consider new sanctions targeting Iran that violate America’s JCPOA obligations, the EU should take immediate steps to amend Council Regulation (EC) No. 2271/96 to add those U.S. sanctions whose application was ended pursuant to the nuclear deal. This regulation was instituted following Congress’s passage of the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA), which imposed sanctions on foreign parties investing in Iran’s energy sector and inaugurated European frustration with U.S. attempts to impose sanctions on an extraterritorial basis.

Formal amendment of Council Regulation (EC) No. 2271-96 would have the express purpose of guarding against efforts of the Trump administration to impose sanctions on Iran inconsistent with America’s JCPOA obligations. Because such U.S. sanctions would have extraterritorial application and would run interference on EU attempts to develop and strengthen commercial relations with Iran, this amendment would be for the express purpose of: A) Insulating the JCPOA from U.S. attempts to torpedo on the agreement; and B) Protecting European interests in developing a multi-faceted relationship with Iran. The institution of new U.S. sanctions provides a ready basis for the EU to assert its prerogatives vis-à-vis the JCPOA.

5) Help Facilitate Iran’s FATF Compliance

The European Union should encourage member states to provide the technical expertise required for Iran to amend its anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regime to ensure it has the opportunity to come into full compliance with the global standards promulgated by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). So long as Iran remains on FATF’s “blacklist,” the willingness of first-tier EU financial institutions to engage their Iranian counterparts will be exceptionally limited, thereby continuing to frustrate European efforts to develop and strengthen normal, sustained commercial relations between the EU and Iran.

Such measures should include EU-wide encouragement of private parties to lend their technical expertise over AML/CFT compliance matters to Iranian banks seeking to put into practice amended Iranian laws and FATF recommendations. To the extent necessary to ensure the provision of such technical expertise, the EU should encourage the United States to provide legal authorization for American citizens to engage in the provision of such technical expertise, particularly insofar as the willingness of European firms to engage Iranian parties in these matters may be dependent on limiting the costs of U.S. sanctions compliance.

6) Instruct European Central Banks to Process Iran-related Payments

Perhaps the biggest roadblock to full implementation of the JCPOA is the ability of Iran to attract foreign investment by way of access to capital. In a world of global banking infrastructure interconnectivity, access to financing for major industrial projects requires prime banks to provide capital at competitive interest rates. Iran is currently viewed by many as having too much “political risk” associated with investment, but this is not often the reason why European banks decide to turn down Iranian business. They do so under the pretense that major European financial institutions are so intertwined with American financial system, be it as counterparty to transactions with American banks or holdings of U.S. dollar reserves. This exposure and the legal compliance that accompanies it has limited the appetite for prime European banks to jump into the Iranian market, despite Iranians longing to embrace European companies for their technological expertise and global reach.

For Europe to regain its footing in Iran, the European Central Bank (ECB) must look to support small to midsize banks under its regulatory authority that have no (or very little exposure) to the U.S. financial system. The ECB along with the CBI (Iranian Central Bank) should designate a few Iranian and European banks as certified to carry out trade and investment for EU companies in Iran. These banks can then have as their counterparty Iranian banks that meet EU regulatory and standards for best practices (as well FATF) and have the backing of the CBI in Tehran. This “safe banking zone” can expand over time as both Brussels and Tehran become comfortable and see that it is working to their satisfaction. The EU needs to expand from banks that only operate as clearinghouses for Iran related transactions and also encourage these banks to underwrite trade and investment with Iranian counterparties. If these banks feel comfortable in the backing they receive from Brussels and the correct financial incentives are in place, it would be a victory for the EU’s commercial aspirations in Iran, help Iran derive the economic benefits promised in the JCPOA, and aid Europe’s efforts to mitigate continued U.S.-Iran conflict escalation.

7) Establish a Joint EU-Iran Bank

Perhaps the boldest step Europe and Iran should take is to create a EU-Iran bank with no ties to the U.S. banking system. Such a bank could be a 50-50 joint venture with multiple Iranian institutions that meet stringent compliance requirements (shareholders are Iranian nationals or companies that are not on UN, U.S. or EU sanctions lists) along with European stakeholders who wish to participate. The bank would be capitalized with Euros, receiving license to operate both in the EU and Iran by the respective central banks of each. Its board would maintain a rotating chairmanship between the two sides every two to three years, which would cast deciding votes on issues. However, the better route for the EU to take is to have a majority stake in the bank to always maintain the chairmanship so as to insist on the highest level of compliance and make sure it directionally can control the bank and safeguard it from allegations that it is being run by nefarious Iranian interest—as is so often the case from U.S. institutions against Iranian banks.

The purpose of such a bank would be like the banking channel: to make sure EU companies have a mechanism where they can invest in Iran, access financing, and repatriate proceeds of income they generate from Iranian business back to Europe. Iran could also start processing transactions and accessing trade finance more easily than is the case today. All letters of credit issued by Iranian counterparties would be in Euros or Swiss Francs. The European shareholders would be smaller financial institutions with little or no exposure to the U.S. banking system.

8) Right-size Expectations on Ballistic Missiles

The EU should submit a request to Tehran for dialogue without preconditions on Iran’s ballistic missile program as a component within the aforementioned Strategic Partnership. Europeans honed in on this issue while trying to prevent Trump from abandoning the JCPOA, but they should proceed carefully and avoid cutting off their nose to spite their face. An Iran that fully implements its JCPOA commitments is clearly not working to deploy ballistic missiles designed to carry nuclear weapons—because it has rejected the motive of deploying such weapons. Moreover, Iran has unilaterally announced the limitation of its ballistic missile range to 2,000 kilometers. While this gives Tehran regional reach, Saudi Arabia’s missiles have a range of approximately 4,000 kilometers, and Israel’s missiles are equipped with nuclear weapons.

Therefore, Western arms exports to Riyadh, Tel Aviv, and Abu Dhabi should be re-evaluated because the context for security and conflict in the region has clearly changed since Trump entered office. For example, missile sales to Saudi Arabia are typically seen as a normal aspect of partner reassurance. In the current climate, however, it is far more destabilizing and escalatory. Arming these countries to the teeth makes the EU’s ballistic missile efforts vis-à-vis Tehran less likely to succeed—particularly when each of their defense budgets dwarfs Iran’s. The Iranians now view such sales as the EU undermining their security, given the increased threats they face from Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the UAE. A wiser course of action for Europe would be to follow Germany’s lead and halt weapons exports to Saudi Arabia until their hostile regional policies cease.

Can Europe save the Iran deal? Yes. Will doing so require a demonstration of political and economic independence from United States not seen this the end of World War II? Yes. Facing this daunting reality, skepticism is understandable and dissent within the EU is likely. Few would envy the dilemma facing Europe. However, the decisions it makes today will cement the realities of tomorrow. Europeans must learn the right lesson from their failed negotiations with Trump’s team over the past year: Trump is a bully, and if you give him an inch, he will take a mile. Europe can push back in pursuit and protection of global interests, or it can continue to get pushed around to its detriment. Europeans did not ask to be put in this position by Trump, but here we are. In the days and weeks ahead, as Europeans deliberate over whether or not to take a stand, they should keep one question in the front of their minds at all times: If not now, when?

Reza Marashi is research director at the National Iranian-American Council. He previously served in the Office of Iranian Affairs at the U.S. Department of State. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Foreign Policy, Atlantic, and National Interest. On Twitter: @rezamarashi.

The Lam-Alif Artist

When the Egyptian uprising broke out in 2011, Bahia Shehab, associate professor of design at the American University in Cairo, had just finished working on a book and art installation. No, A Thousand Times No collected a thousand variations of the word “no” on items of Islamic history dating back more than a thousand years in locations as far-flung as Spain and China. Nine months later, she found herself spray-painting the different letterings on the streets and walls of Cairo. “No to beating women,” “No to a new Pharaoh,” “No to burning books.” Her work has not only earned her many honors, including a place on the BBC’s “Women 100” list in 2013 and 2014, but also led to her becoming the first Arab woman to ever win the UNESCO-Sharjah Prize for Arab Culture.

Shehab, 40, is a recognized Egyptian-Lebanese artist, designer, and art historian whose art has been displayed in street graffiti, exhibitions, and galleries all over the world. Shehab’s work focuses on issues of identity and injustice, particularly in relation to socioeconomic, political, and gender discrimination. “Everything is a manifestation of that singular idea of human rights. I am concerned with women’s rights because they are part of human rights,” she said in an interview with the Cairo Review.

Shehab believes her award-winning art installation resonated so deeply because of its relevance to humanity. “When you feel all the oppression and bad things that are going on around you, you feel like you just want to say no.” The title of the work highlights a common Arab expression: “No, a thousand times no.”

Shehab is best known as a “calligraffiti” artist, who blends Arabic calligraphy and typography with graffiti. As a scholar of the Arabic script, she believes it opens a window into learning about Arab identity. In her research on the Lam-Alif (the two Arabic letters that make up the word “no”), she thought: “Imagine all the culture that produced this one letter. If you can create a thousand shapes for one letter, imagine the kind of knowledge that this civilization had.” Very often, her passion to document art history has brought her to the streets. While she can no longer do street art in Cairo because of the city’s “inaccessibility,” she has been painting graffitied quotes from Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish on walls in cities from China, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, and Italy to Japan, Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States.

Shehab is also the founder of a groundbreaking graphic design program at AUC featuring a curriculum centered on the visual culture and heritage of the Arab World. She believes that this approach will help students design the solutions of the future. She also developed a graphic design online course in Arabic for the Queen Rania Foundation’s Edraak Platform, which 50,000 students registered for. She is working on another to be released later this year.

Speaking about her UNESCO-Sharjah Prize, Shehab tells the Cairo Review, “It’s a shame that I am the first Arab woman.” She adds that more important than fame and recognition is that laws change in favor of women and that women’s movements earn more rights. Shehab intends to use the spotlight to continue to showcase issues of gender inequality and human rights violations. She underscores the commonality all women face in experiencing oppression but stresses that progress still needs to be made in the Middle East. “We [Arab women] face double the challenge but women’s movements in the West have been working for almost a hundred years and just now they are reaping their rewards. So, we still have a long way to go.”

Most recently, Shehab worked on a video-photo project to raise awareness on the need for greater government attention to preventing blindness in Africa. The project showcases the individual members of an all-women blind orchestra troupe in Egypt. She chose to feature the women playing their instruments alone in a hallway before and after a concert in order for the viewer to “relate to the loneliness of being a woman, veiled, and blind in Cairo. It is a poetic reflection of who they are.”

Shehab is currently co-authoring a book on the history of Arab graphic design. She leaves little doubt that she is prepared to continue her quest for greater representation of Arab women in art and design circles. In every way, she models the advice she gives to rising female artists: “Work hard, love what you do, and you can get anything you want.”

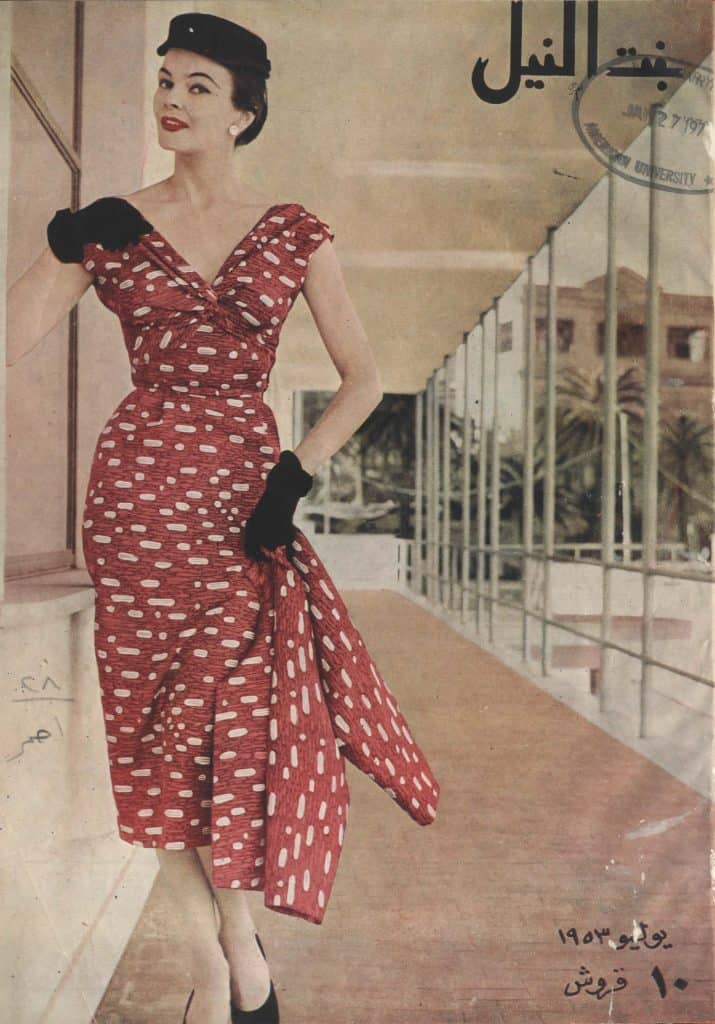

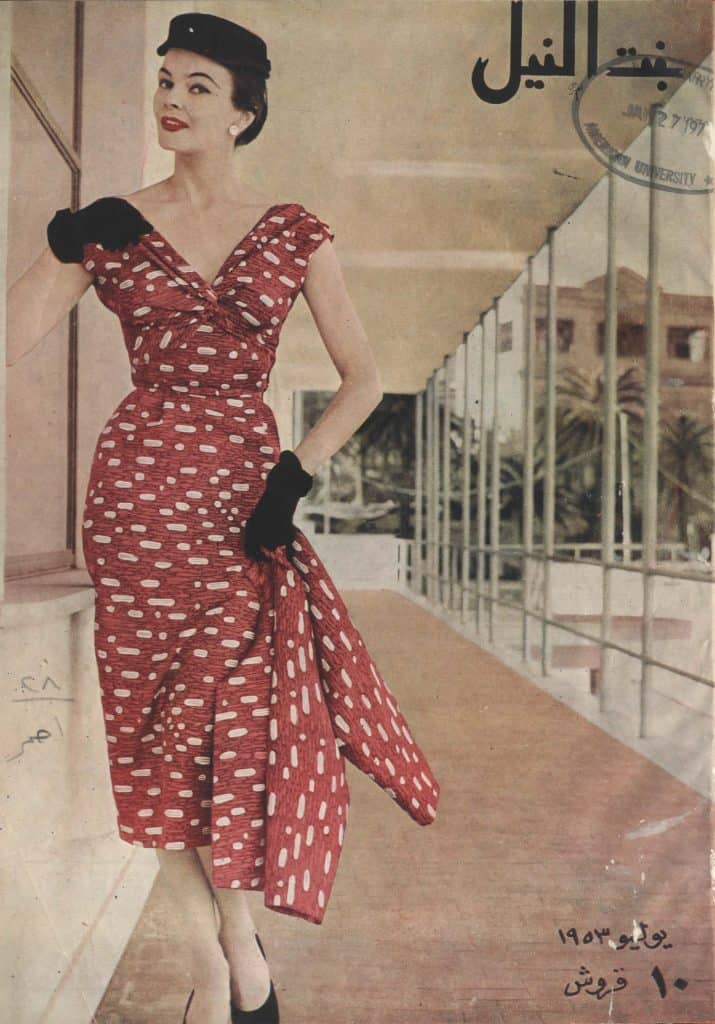

Daughter of the Nile

Doria Shafik, Egypt’s best-known feminist and suffragette, started the women’s journal Bint Al-Nil at a low point in her life. She wanted to counter the public’s image of her as being “too French.” As editor-in-chief of La Femme Nouvelle, a Francophone culture magazine, Shafik was often associated with its publisher Princess Chevikar, the vengeful and publicly hated divorcee of King Fouad of Egypt. This association caused Shafik to be excluded from the Egyptian Feminist Union and regarded as one of Chevikar’s opulent “ladies of the salon de thé”—a tea-sipping detached elite, removed from the suffering of common Egyptians. Moreover, Shafik was bored with her job as a French-language inspector in the Education Ministry, and was frustrated with the limited progress made on women’s rights in her country. Her burning desire was to enter public life. To her, journalism was the gateway into that world.

The glossy Arabic-language Bint Al-Nil journal appeared on newsstands in November 1, 1945. It sold out within the first two hours, and did not stop circulating until 1957, when the government forced its closure. With a name derived from Shafik’s own self-identification as the “daughter of the Nile,” the purpose of the journal was to awaken Egyptian and Arab women to the women’s rights movement.

July 1953 cover for Bint Al-Nil Journal. Courtesy of the Rare Books and Special Collections Library.

Looking through the select articles of the journal made available by the American University in Cairo, one encounters an archetypical lifestyle magazine, featuring motherhood tips, philanthropic news and profiles of celebrated women in history, but the occasional dip into activism is hard to miss. Shafik used Bint Al-Nil as a platform to broadcast her radical feminist voice and promote better conditions for women.

The magazine successfully turned heads at a time when the women’s movement was buried in the heightened nationalism that marked the run-up to the Gamal Abdel Nasser-led revolt against the British and the ruling monarchy in 1952. Close reading reveals the evolution of Shafik’s own intellectual thought and entrance into public life, which led her to some of the most profound feminist undertakings in her lifetime and in the Egyptian suffrage movement.

The journal also raises questions about the difficulties of generating a feminist discourse within a culturally impenetrable and patriarchal society in a country that gave women the right to vote only in 1956. As the editor, publisher, and owner of Bint Al-Nil, Shafik faced such challenges head-on. The first such challenge came from within the publication. In the first two years of Bint Al-Nil, Shafik’s editorial partner, Ibrahim Abdu, toned down her language in her editorials after they had been translated from French in order to avoid the “Al-Azharites’ immediate wrath and violent opposition to Bint Al-Nil.” At the time, Abdu claimed that Al-Azhar—Egypt’s top religious body—was strongly against women entering the same workforce as men. Aware of the mounting opposition to her project, Shafik fought hard to maintain editorial and financial independence.

By 1949, four years after the journal’s launch, Shafik was fighting criticism from the public and the press that she was inciting women to ignore their domestic responsibilities and engage in politics. Three times during the span of a year, she churned out editorials defending her publication’s mission and identity, arguing that it was neither a political organization nor did it aim to embolden women against religion. In the May issue of 1949, Shafik maintained that the magazine only hoped to encourage women to fight for their political rights. That women’s lack of political emancipation was at the core of their oppression pervaded Shafik’s feminist thinking.

In another editorial, she scoffed: “What will our men in Paris say when they are asked about the status of women in political life? Do they say they are at its bottom? […] Or do they say that they are at its zenith but are not equal to an illiterate carpenter or shoemaker who can fingerprint the ballot.” She signs off the piece with a call to parliament to grant women suffrage.

An editorial written by Doria Shafik in the February 1956 issue of Bint Al-Nil journal. Courtesy of the Rare Books and Special Collections Library.

Understandably, Shafik was locked in a fight with the public, whose antagonism toward her was deepening. As she intensified her efforts to bring women political and social rights such as curbing one-sided divorce and polygamy, her foes multiplied. In 1948, when she created a union named after the journal, she came under attack from the clergy, conservatives, and progressives alike, and even the older generation of feminists, who were students of famed feminist Huda Al-Shaarawi. Although Shafik’s feminism reconciled Islam with equality and modernity and aimed to reconceive public life for women through political participation, her beliefs were hardly tolerated.

Against this backdrop, Shafik’s political consciousness radically shifted from a bourgeois understanding of women’s rights to a more class-conscious, and later militant, kind of feminism. By the early fifties, Shafik began to enter the political fight, Marxist lawyer Loutfi Al-Kholi, who was involved in the work of the magazine, noted. “She transformed Bint Al-Nil into a movement that related the liberation of women to the larger political struggle,” he is quoted in Cynthia Nelson’s biography of Shafik as saying.

In February 1950, an intensity emerged in Shafik’s writing. In an editorial addressed to the Egyptian prime minister, she writes with incisive irony: “Why are we doubting the prime minister’s words? Didn’t His Excellency, Mustafa Al-Nahas, announce last summer that the Wafd [Party’s] primary goal was to grant Egyptian women the right to vote?” It was time to change tactics, she added—“to assail men, surprise them right in the middle of injustice, that is to say, under the cupola of parliament.” Her bold words hinted at a major protest that she was planning.

In the afternoon of February 19, 1951, Shafik, along with 1,500 women, stormed parliament. They held a four-hour demonstration before being received in a parliamentary office and extracting a promise from the president of the senate to take up their demands for suffrage, amendments to the personal status law, and equal pay with men. Although a draft bill was in the pipeline, the prime minister blocked shepherding it through parliament.

Shafik stood trial for staging the sit-in, and her case was postponed indefinitely. Then, after a group of army officers calling themselves the “Free Officers” took over the country in July 23, 1952, things slightly looked up: Shafik praised the new rulers and wrote that they would herald “the beginning of a renaissance” for women. But the officers’ authoritarian bent soon became apparent, and in response to the lack of female representation on the constitution-writing committee, Shafik held a hunger strike.

Lasting for ten days, the strike turned Shafik into an international figure and earned Egyptian women a written promise by the government for full political rights. However, the 1956 constitution granted women only vaguely-worded political rights on the condition of literacy. Unassuaged, Shafik headed an all-out confrontation against Nasser, protesting in the Indian embassy and holding a “hunger unto death” strike against what she viewed as his dictatorial rule. Nasser himself ordered Shafik’s house arrest and banned her publication. Shafik withdrew into an eighteen-year period of seclusion before allegedly throwing herself off the balcony of her apartment.

Shafik’s solitary demise was shocking for a woman who had pioneered feminist consciousness-raising and championed women’s suffrage and advancement for many years. Her publication and organizing are key to Egyptian women’s emancipation even today. Finding solace in poetry during her final days, Shafik reflects on her broken legacy and the lone march ahead: “My name begins with a D/and I am a woman…Daughter of the Nile/I have demanded women’s rights/My fight was enlarged to human freedom/And what was the result?/I have no more friends/So what?/Until the end of the road/I will proceed alone.” But it is only after her death that Egypt began to mourn the loss of Shafik and understand the sacrifices she has made for feminism.

Oriental Hall, etc.

The Saudi-born Lubna S. Olayan, CEO and deputy chairman of Olayan Financing Company, delivered some hard truths about the Arab World. Eighty-five million people in the region are illiterate. Poverty affects almost a quarter of an Arab population of 150 million, and 50 percent of the world’s refugees are Arab. And yet, young people can be agents of change, argues Olayan, delivering AUC’s Nadia Younes Memorial Lecture, established in honor of the Egyptian UN official killed in the bombing of UN headquarters in Baghdad in 2003. “How can we be surprised by the wakeup call young people are giving us?” she rhetorically asks, referring to the 2010–11 Arab uprisings, adding that “our young people are looking for the opportunity to contribute.” Education reform is the vital first step. As a child, Olayan remembers her father moving her and her sisters from Saudi Arabia to Beirut because there weren’t any schools available for girls in Saudi Arabia. Today, Olayan is paying back this opportunity by chairing Alfanar, the first venture philanthropy organization in the Middle East. Arab governments, she says, should match individual and company donations to encourage philanthropy. “What better way to start than by focusing on social impact?”

Is a Nuclearized Middle East Inevitable?

The recent statement by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman that his country would acquire nuclear weapons if Iran had them has understandably raised serious concern, albeit for the wrong reasons. The statement raised red flags because the crown prince openly said that Saudi Arabia would enhance its military capacity to counterbalance those of its neighbors, particularly Iran.

The Middle East is in a state of turmoil from North Africa through the Levant and southwards to the Arabian Gulf. A natural consequence of ongoing conflicts is militarization, be that at the level of conventional armaments or weapons of mass destruction. Arms expenditures—whether by acquisition from abroad, or as part of domestic industrial production—are at an historic high.

The Saudi crown prince was actually only projecting policies that neighbors, as well as the major powers globally, have pursued since the beginning of the Cold War. In fact, both Israel and Iran have greatly enhanced their domestic military industrial capacity, including nuclear technology. Israel is reported to have over 200 nuclear warheads, and has not signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Both countries have acquired sophisticated delivery systems.

Despite Iran being a full member of the NPT, concerns emerged over whether its civilian nuclear program could serve as a cover for the development of a military nuclear capability. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between Iran and the P5+1 was meant to address these concerns, but seems to have fallen short because of worries over the relatively short “breakout time” for Iran to achieve a military nuclear capability once the restrictions imposed by the agreement expire. There are also concerns regarding Iran’s ballistic missile capacity, which is not part of the agreement. And of course, Iran’s aggressive policies and hegemonic regional ambitions only add to the prevailing concerns over its nuclear program.

The real concern should be that the Saudi crown prince’s statement could be read as a warning that a nuclearized Middle East is no longer a distant prospect. If left unchecked, these developments will severely destabilize an already turbulent regional security situation. Ignoring the threat of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East is simply no longer tenable.

Time is of the essence. Middle Eastern states will seek to augment their military capabilities, and enhance their domestic military capacities if these concerns are not met. This will include amassing more weapons, at a higher level of sophistication. Acquiring more weapons capacity in the nuclear domain will be one of the options.

A preferable alternative would be to forthrightly address the emerging nuclear threats in the region by rectifying the asymmetries in nonproliferation commitments, and encouraging regional adherence to the various treaty frameworks that make up the global nonproliferation regime with regards to nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, as well as their means of delivery.

Rather than abrogating the P5 + 1 nuclear deal with Iran, a better approach would be to augment it with a comprehensive region-wide approach to the proliferation challenge in the Middle East. Egypt has long called for the establishment of a zone free of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East. All states in the region—including both Israel and Iran have—expressed support for the establishment of such a zone. Egypt itself has already made its adherence to international agreements that prohibit chemical and biological weapons contingent upon Israel joining the NPT.

The concerns about breakout time in JCPOA enters into play after approximately fifteen years. In moving forward, the best option would be to create a negotiating, working group from Middle Eastern states, under the auspices of the permanent members of the UN Security Council, with the participation of the International Atomic Energy Organization, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization as the relevant technical bodies of the major nonproliferation treaty regimes. This format would accommodate Israel’s and the United States’s preference for regional negotiations.

At the same time, through the participation of the P5, there is a wider international cover that addresses Iranian and Arab concerns.

The task of the working group would be to negotiate an agreement to create a Middle East Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone (MEWMDFZ) and have it enter into force before the provisions enshrined in the JCPOA expire. Arrangements would also be made to expand the scope of the original proposal to include measures to contain the means of delivery of these weapons.

As a preliminary indication of seriousness, the negotiating parties would be asked to deposit letters with the UN Security Council committing themselves to this objective and to abstain from further developing their weapons of mass destruction capacities while negotiations are ongoing.

Such a zone can be achieved under a single wide-ranging regional framework that addresses all weapons of mass destruction in the region, as well as complementary regional verification arrangements to ensure compliance. It can, however, also be also be achieved initially through universal adherence to existing international agreements prohibiting these weapons coupled with, if necessary, additional verification measures. The optimum approach would be a hybrid of both.

Each of the three international technical agencies should be invited to suggest confidence-building measures in their areas of expertise to create a better environment for negotiations. They can also be called upon to assist in developing verification measures commensurate with such agreements. And, the P5 could constructively suggest a series of other measures regarding good neighborly relations to decrease bilateral tensions in the region.

The international community, with the Middle East at its core, can either engage in bold, although difficult negotiations, or face the inevitable dangerous ramifications of further weaponization and nuclearization of the Middle East.

Nabil Fahmy, a former foreign minister of Egypt, is the dean of the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the American University in Cairo. He served as Egypt’s ambassador to the United States from 1999–2008, and as envoy to Japan between 1997 and 1999. On Twitter: @DeanNabilFahmy.

“My principle is to unveil the mind”

Physician by profession and radical feminist by vocation, Nawal El Saadawi, 86, has been dubbed the “Simone de Beauvoir of the Arab World.” El Saadawi is most known for her fierce advocacy against the issues of female genital mutilation, Islam, and the veil. Her controversial views have led to her imprisonment, the issuing of death threats against her, and ultimately, her having to flee Egypt with her family. El Saadawi returned to her homeland and took part in the 2011 uprising, championing women’s rights through calls for constitutional amendments and for the establishment of a union for Egyptian women. El Saadawi’s most recent public efforts include her plans to launch an institute that promotes thought and creativity. The Cairo Review conducted this interview with El Saadawi on April 8, 2018.

CAIRO REVIEW: What got you into writing literature? How did working in the medical profession influence that, if at all?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: I started writing when I was a child in primary school. I kept a memoir—a diary—in which I wrote letters to God, to my parents, to my teachers, and to King Farouk, but all these letters were kept secret or burned.

And I never wanted to be a medical doctor but I became a doctor just to please my parents. However, studying medical sciences and examining sick men and women gave me a lot of material for my fiction and nonfiction.

CAIRO REVIEW: Why was female genital mutilation the most recurring and sensational topic in your early writing?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: Female genital mutilation and male genital mutilation are very serious problems. To cut healthy children is a grave crime, but medical doctors, nurses, and midwives were ignorant, locally and globally, and religious men and women of all religions supported these crimes.

The global commercial media made it sensational but I challenged all that by writing scientifically and truthfully in my fiction. However, female genital mutilation is only one of the topics I write about, and I wrote about many more, which were ignored by literary critics and the global media.

CAIRO REVIEW: Do you still feel it is an important issue today?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: In Egypt today, 90 percent of females and 100 percent of males are cut. The law forbids female genital mutilation but not male genital mutilation. Even the United Nations did not prevent male genital mutilation. All these operations have serious complications, physically and socially, and are crimes against children who cannot fight back.

CAIRO REVIEW: What is your opinion about the state of feminism in Egypt today?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: We have fragmented women’s organizations called NGOs; they are semi-governmental organizations. They receive a lot of money globally, but their effect is very little. The governmental women’s organizations are obedient to the government and cannot struggle against class, and patriarchal and religious powers.

CAIRO REVIEW: Immediately following the 2011 uprising, there was the idea of establishing an Egyptian union for women. Do you still think this is necessary?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: The Egyptian Women Union was aborted (like the January 2011 revolution) by the Muslim Brotherhood and the government at that time. Women in Egypt need a women’s political party not only an organization, to be liberated from the political, religious, colonial, and capitalist powers.

CAIRO REVIEW: Many of your novels such as Memoirs from the Women’s Prison, Woman at Point Zero, and Love in the Kingdom of Oil deal with imprisonment, literal or figurative. What does it take for your heroines to escape their imprisonment?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: All creative works help to open the minds and illuminate oppressed women and men, as well as, assist in raising their consciousness, and therefore they organize and struggle together to liberate themselves from all types of prisons. Most of my heroines are fighters in different ways.

CAIRO REVIEW: How can Memoirs from the Women’s Prison be relevant today, especially with so many political prisoners languishing in jails?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: I think prisons are a global-local (glocal) problem, not only in our country. Democracy is false in the classist, patriarchal, and racist system that it exists in. Anybody can go to prison if he or she challenges the status quo in any country, and so I cannot compare between prisons today because they are all forms of postmodern slavery.

CAIRO REVIEW: There is emerging literature mapping a new geography of sexual politics in the Middle East. Does resistance have to be transgressive as your novels show?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: Resistance can take different forms in different situations, but women cannot be liberated by covering or uncovering their bodies. Veiling and nakedness are two faces of the same coin, encouraged by capitalist imperialism and religious patriarchal fanaticism. My principle is to unveil the mind.

CAIRO REVIEW: To what extent are your works autobiographical?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: Yes, the writer is inside his or her novel. I do not separate the self from the other. In all my novels, there are parts autobiographical, parts fiction, and parts reality. There is no separation between fact and fiction.

CAIRO REVIEW: Your last play God Resigns in the Summit Meeting, which explores religious paradoxes and the final resignation of God from his role, led to a publisher recall and accusations of heresy and insulting Islam. Why did you feel the need to write this work? Do you accept criticism of the play?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: I accept any criticism of my work, if it is objective and based on critical thought, but I refuse threats or insults of fanatic religious political people.

I wrote this play because the characters and ideas in it have haunted me all my life, since childhood, since I wrote my first letter to God in primary school. The urge to write a novel or a play is not voluntary, and has many reasons and no reason at all.

CAIRO REVIEW: Can you share your experience of exile both in Egypt and in the United States?

NAWAL EL SAADAWI: Exile can be very useful if we continue to work and produce creatively. Exile in Egypt or outside Egypt was very useful to me, but exile in the United States or Europe or other places was more productive and inspiring to me than in Egypt. The threats against my life were greater at home than far away. In fact, I learned a lot from living in different places with different people and different cultures.

“We want to see real results”

Since 2008 Rothna Begum has been advocating for women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa region, first with Amnesty International then with Human Rights Watch (HRW). Having studied Islamic as well as human rights and international law, her interest in the topic drew her to work in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries where sharia is either the law or the source of the law. Given the huge population of female domestic workers coming from Asian countries to the Gulf and their vulnerability to different types of abuse, this soon became Begum’s main area of focus. On April 16, Begum spoke to the Cairo Review about the state of migrant domestic workers in the region and efforts to protect their rights.

CAIRO REVIEW: Have you seen progress since you first came into this field ten years ago?

ROTHNA BEGUM: When I started there was a serious deficit in protection for workers. Migrant domestic workers face the triple forms of discrimination: one, they are women; two, they are migrants; three, they are specifically domestic workers. In the Gulf countries, domestic workers were long excluded from labor laws. As women, they’re more vulnerable to sexual abuse, and also trapped in the homes as domestic workers so they are really liable to both physical and very intimate forms of abuse unlike other migrant workers. And, of course, specific racial discrimination comes into that.

In the Gulf, we have seen a series of reforms recognizing the rights of domestic workers, starting with Jordan in 2008, Bahrain in 2012, Saudi Arabia in 2013, Kuwait, which had the most progressive law in the Gulf region in 2015, and Qatar and the UAE in 2017. The last Gulf Cooperation Council country is Oman, which has a 2004 regulation of domestic workers but has no penalties so it’s not effectively any form of labor law.

But the other big problem is the kafala system. The idea that your entire legal status is based on your employer’s permission gives a huge amount of control to the employers to become as abusive or exploitative as they like. However, HRW has helped play a part in developing the global treaty on domestic workers’ rights, the Convention on Domestic Workers adopted at the International Labour Organization, which was passed in 2011. And because of the work of HRW and other organizations we have seen some changes. The UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have amended some aspects of the kafala system.

The biggest potential change is Qatar, which has committed with the ILO to other reforms, including reforming the kafala system by moving toward a government issued visa for migrant workers. If Qatar actually does reform the kafala system, potentially this could lead the rest of the Gulf region into a different situation entirely.

CAIRO REVIEW: How much are recruitment agencies involved with legal, semi-legal, and illegal recruitment of workers? To what degree are authorities involved?

ROTHNA BEGUM: To start off, in the last two to three years we’ve seen a huge surge in recruitment from African countries, including domestic workers, because Asian countries have stepped up protection for their workers, and also placed bans on their workers coming into the Gulf region due to abuses. The problem is that the Asian countries have had to build up laws and recruitment policies, and figure out protection mechanisms at their embassies to help manage this recruitment and protect their workers. Now, it’s not perfect, but they are decades ahead of countries in Africa.

In terms of illegal versus legal recruitment, for Middle Eastern countries, if you have a visa to come into the country, and then an employer secures you a work permit, it’s perfectly legal. That doesn’t mean you didn’t come in as a trafficked victim. You could have been promised by an agent from your country of origin a certain wage or certain conditions, turn up at the country, and find yourself basically trafficked into forced labor conditions. The system recognizes you as a legal worker, but you’re still a trafficking victim.

On the country of origin side there are recruitment agencies, some of which are registered with the government, but there’s no proper oversight to check whether a worker is going with a registered or unregistered agent. I spoke to registered recruitment agents from agencies that are credited with the government who were committing what you would consider to be classic trafficking or forced labor violations, which they sent to me themselves, because they didn’t see it as bad practice. One agent, for instance, was forcing women to sign a document saying that they would not return early from their contract including under circumstances where they would have fallen pregnant, or had a relationship with their employer, or they could be fined $2,000.

CAIRO REVIEW: Do you really think that these agents don’t realize their actions border on slavery, or at least, forced labor?

ROTHNA BEGUM: Well this agent told me how he prevents workers from leaving their contracts early as a normal protection measure for himself. And he knows that I’m speaking to the government. I think if he knew it was bad practice he wouldn’t be admitting that to me.

The issue is not with this agent particularly, but with the policies and laws and the government. These policies are so bad and have so little to do with the recruitment agencies, that the agent is not actually committing anything illegal. I think there’s a deficit in the understanding of some of these governments about how to protect these workers. Some of these governments are too busy focusing on how they can send their workers over to other neighboring countries. Some government officials and members of parliament may be benefitting from the recruitment, so there’s a whole other issue of public officials who are invested in these recruitment agencies, who realize this is a business venture, and are part of these ventures now. One way to resolve that is to have laws that say that government officials cannot be investing or partnering with these agencies.

CAIRO REVIEW: You mentioned Kuwait as one of the best countries for some kind of legal representation. Why do you think that is?

ROTHNA BEGUM: Kuwait in 2015 was the most progressive in the Gulf region, but that doesn’t mean that’s the case anymore, because the UAE and Qatar have established laws since 2015 which are similar and have their own standards so they vary in their quality. So Kuwait provides overtime compensation which the other two don’t. The UAE provides workplace inspections, which Kuwait has not established when it comes to the homes themselves. So on different points they’re stronger, and weaker on others. The problem is that the abuses have continued in Kuwait because of an inability to properly recognize their rights under the kafala system. So as a worker, even though you now have some rights under the law, how do you claim those rights if you are still tied to your employer?

CAIRO REVIEW: Do you think such a patriarchal, dominant system as the kafala system could ever realistically be reformed?

ROTHNA BEGUM: I think we’re seeing the beginning of it. I think that because of their commitment to the ILO, Qatar will be the first example of seeing whether or not they will actually amend the system.

CAIRO REVIEW: But still maintain the idea that you’re tied to your employer?

ROTHNA BEGUM: Well, Qatar has committed to reforming the kafala system and their commitments have to come through in a way that means they can’t be still trafficking workers into false labor situations. And currently the kafala system is an exploitative environment that allows forced labor situations because of the way it is designed. It traps you with that sponsor. They have to do away with this.

CAIRO REVIEW: How do you feel about the future of migrants in the Gulf?

ROTHNA BEGUM: I have mixed feelings. We have seen some changes in the Gulf region that wouldn’t have happened if there wasn’t a level of commitment and passion and hard work by many organizations and advocates. But the abuses still continue. We want to make sure that those changes are strong, that they come much faster. Gulf countries are succeeding largely on the backs of these workers that have come in the millions; they should not be allowed to get away with the kinds of abuses they have been.

So I don’t want to accept the small achievements as a consolation prize, for the work that has been done. We want to see real results; we want to really see such a cultural change because there’s been a serious commitment by these governments.

But that won’t happen unless there is a serious commitment from countries of origin to their citizen populations and from the international community to say they won’t tolerate this situation where the entire system is designed to have an an easily exploited labor force.

“Our niche is to focus on the most vulnerable and marginalized”

Blerta Aliko heads UN Women Egypt whose main objective is to empower women and reduce gender inequality. Appointed as the country representative in January 2018, Aliko brings over twenty-two years of experience to her position along with new perspectives on how to transform intersecting gender-related issues in Egypt. Most recently, Aliko held the position of deputy regional director for the UN Women Regional Office for Arab States in Cairo, and prior to that has worked with other UN development and humanitarian programs, including UNDP and UNICEF. On April 11, Aliko spoke to the Cairo Review about UN Women Egypt, and how it works closely with the government, civil society organizations, private sector, multilateral partners, and the wider public to empower women socially, economically, and politically.

CAIRO REVIEW: How has your background impacted your approach to UN Women Egypt?

BLERTA ALIKO: What I bring to this position is an in-depth understanding of the context and the unique added-value of UN Women. In order to assist the enhancement of policy and programs supporting women’s rights in Egypt, it is crucial to understand the potential to influence that UN Women has as an organization. UN Women Egypt has a technical niche, a strong national team of experts and a position in the multilateral partner arena, but we also recognize that there is more that we can do to maximize the organization’s potential.

CAIRO REVIEW: What are some of the development projects you are working on?

BLERTA ALIKO: We are currently working on three focus areas. The first area focuses on increasing women’s participation and leadership, particularly through increasing women’s citizenship rights by providing women with ID cards. The possession of ID cards is crucial to exercising citizenship rights, such as the right to vote, work, access services and participate in society. As a result, we have supported the issuance of approximately 450,000 ID cards to women across Egypt.

The second focus is on women’s economic empowerment, which begins with giving marginalized women financial literacy training. UN Women Egypt works with the private sector to engage women who usually work in the informal sector, and employ them in the agriculture labor force through fixed-term contracts, ensuring social security and providing training. And through a project called “One Village One Product,” UN Women Egypt supports communities where women are known to produce a particular product by giving them a comparative advantage that would increase the product’s access to market and, in turn, the profit margin of the women’s enterprises.

The third focus area is ending violence against women. As part of the global “Safe Cities” program, UN Women Egypt is renovating spaces, including creating areas that women can access freely and safely to create commercial enterprises.

CAIRO REVIEW: Female genital mutilation is an issue women face across this region. How has this issue been understood and dealt with from the policy perspective in Egypt?

BLERTA ALIKO: Egypt has managed to decrease female genital mutilation in the younger generations from 74 percent to 61 percent. The penalty for female genital mutilation has now increased to a sentence of up to seven years in prison. Combatting female genital mutilation is also part of a social movement led by a variety of influencers such as women’s rights advocates, doctors, and religious scholars, among others influencing Egyptian families to stop the practice. The movement on combating female genital mutilation in Egypt drove decision makers in Egypt to place it on the national agenda of the Egyptian government, launching the “National Strategy and Program Against Female Genital Mutilation.”

It is widely recognized that women themselves play a critical role in perpetuating the female genital mutilation practice against their own young daughters. Therefore, I believe their further empowerment, education, and access to employment would have a strong impact on preventing and reducing the practice of female genital mutilation. Role models too are critical as they have a positive and pivotal influence on the mass population.

CAIRO REVIEW: You worked in Liberia, Myanmar, Haiti and Yemen, can you elaborate on how the challenges in Egypt differ from these areas you have dealt with in your career?

BLERTA ALIKO: Every context is different and as a professional it is your responsibility to learn and understand your own professional and personal environment. With regards to women’s empowerment, what is important is to understand the root causes of the marginalization of women and why patriarchal repressive norms continue, and to be able to find effective strategies for reducing gender inequality. Our niche is to focus on the most vulnerable and marginalized. That is where we need to support this segment of women, in order to have inclusive communities, more developed communities, and more progressive households.

In Egypt’s context, for example, we have one of the most progressive constitutions promoting women’s rights, as well as a very solid National Strategy on women’s empowerment demonstrating the political will from the government to advance women’s rights as the accelerator for Egypt’s sustainable development.

CAIRO REVIEW: What initiatives do you hope to accomplish?

BLERTA ALIKO: One of our objectives is to increase efforts to tackle violence against women, be it domestic violence or sexual harassment in public spaces—considering how crucial the prevalence of violence against women is as a fundamental development indicator. Secondly, we aim to champion and create opportunities for inclusive development. By “inclusive” I mean a significant increase of women in the job market and their financial inclusion. We need to make sure that the employability of women does not come at the expense of women being discriminated against in the job market.

Furthermore, we also have upcoming local council elections. The constitution grants women 25 percent of seats in the local councils. This means that more than 25,000 seats can be occupied by women. Egyptian women need to take hold of those seats, but we need to work very hard to support them and support their capacities when exercising their functions. Women will be judged on how they will be performing, which is why performing in positions effectively—by not only filling seats with women—will be important. We are convinced that if we have very strong, capable candidates and we support them appropriately, our local development plans will prioritize gender equality, and will be more gender responsive.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Educated, But Will She Work?