Syria: The Illusive Settlement

The best way to describe the current Syrian quandary is to borrow from Winston Churchill’s assessment of what he considered the complex nature of the former Soviet Union: popular grievances wrapped in regional rivalries inside big power competition.

A bus blocks a road amid damage on the Salah Al-Din neighbourhood frontline in Aleppo December 6, 2014. REUTERS/Mahmoud Hebbo

Ten years of war has brought about untold suffering to the Syrian people; more than 500,000 have died and, according to the World Bank, more than half the country’s population has either immigrated or is internally displaced. 60 percent of its pre-2011 gross domestic product (GDP) has been lost, and today, more than 80 percent of the population is living below the poverty line compared to only 10 percent in 2011. The World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that 14.2 million out of the 16 million that remain in the country are considered food deficient. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reports that 2.4 million children have no formal education compared to 2011, when primary school enrollment was at 97 percent. Since 2011, 40 percent of the education infrastructure has been destroyed. To summarize the extent of the calamity in a single figure, it is estimated that the economic cost of the Syrian civil war exceeds $1 trillion.

The conflict in Syria did not just happen—it was waiting to happen. Underlying factors were brewing for some time. Both internal problems as well as regional dynamics converged to bring about this tragic fate to the Syrian people, and the Arab Spring was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

To end this tragic conflict, first we need to clearly identify the internal and external factors that caused, and later exacerbated the Syrian conflict, and second, we need to find a means to generate mutually reinforcing internal and external dynamics that allow for positive movement on a political settlement.

While internal factors, or grievances, were the principal causes of the uprising of the Syrian people in 2011, it was the external factors, manifested in foreign interventions, which transformed it into a full-fledged conflict and proxy war. Therefore, a political settlement is now possible only if all forms of foreign interventions are squarely addressed. Only then will it be feasible to reach a political settlement among Syrians.

In this first part of two installments, I will tackle both the domestic and external factors that have exacerbated the situation. The second part will explore how to generate an internal dynamic that produces a domestic critical mass in support of orderly change in Syria as well as an external dynamic that best deals with foreign interventions. The interaction of both dynamics should accelerate a political settlement.

Domestic Disturbances

Foremost among the domestic factors that caused the conflict to erupt is the nature of the political system that has been ruling Syria for decades. It is a system caught in a time warp, which refuses to exhibit the flexibility and imagination required to deal with the grievances and aspirations of its people and is unable to navigate the treacherous, and sometimes conflicting, currents and forces shaping the unfolding international order which has been in transition since the abrupt fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. In the past three decades, the world has witnessed globalization and insular nationalism; liberal economic policies and increased state intervention; open, and free trade and increased protectionism; increased movement of peoples across borders and erection of barriers, both physical and institutional, to stop the flow; free flow of information and the malicious manipulation of such information; unprecedented wealth coupled with what could be possibly be the most skewed income distribution in history; uncertainty from the wanton use of force, whether through endless conflicts or and terrorism; economic and political marginalization, environmental degradation, and now, pandemics.

A single political party, the Baath party, has dominated the scene for over fifty years, thus stifling any opportunity to channel the mounting grievances. Without these channels, the population found solace in communities—ethnic, religious, or tribal—thereby undermining the very fabric of the cohesive yet multi-dimensional character that has characterized Syria over centuries. When the conflict broke out, this dangerous trend accelerated.

The failures of the system were compounded by adverse economic factors. Prior to 2011, Syria was a case of uneven development, where the government pursued policies designed to achieve high rates of growth without undertaking complementary political reforms required to sustain such policies. Without the necessary transparency and adequate distributive measures, corruption and the creation of crony capitalists—who exploit the economic reforms to further their narrow interests—become the dominant features of the system. As a result, popular grievances multiply. Moreover, a prolonged drought from 2007-2010 accelerated migration into already crowded cities, inflaming the resentment of the rural poor toward wealthier urbanites. A widening gap between the rich and poor, triggered by the liberal economic policies pursued by the government, created social tensions that the sclerotic political system could not address.

To avoid making the necessary political reforms, the government also brandished its revolutionary credentials by emphasizing resistance to Israel and espousing anti-Western policies to divert the attention of its domestic base away from demands for reforms.

Taking its cue from a policy adopted by Nasserist Egypt, Damascus divided the population into Ahl Al Thiqa (the Trustworthy) and Ahl Al Khibra (the Experienced, i.e. professionals) thereby emphasizing loyalty over competence in an environment of an oversized public sector and lack of sufficient numbers of subject matter experts among the loyalists. This was probably the beginning of the regime’s reliance on the Alawites—a historically under-privileged off-shoot sect of Shiism to which President Hafez Assad belongs and which constitutes around 12 percent of the Syrian population. Gradually, the Alawites took control of the levers of political power—army, security services, and government bureaucracy—and to a lesser extent economic power, leaving the rest of the population playing an increasingly marginal role.

A growing resentment toward the Alawites resulted. This was seized upon by the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), which had been waiting to take its revenge since the brutal suppression of the Islamist campaign of violence which culminated in the 1982 uprising in the northern Syrian city of Hama in which up to forty thousand are estimated to have been killed.

A profound schism in society, borne of the role of religion in the Syrian state, is a further complicating factor. The overwhelming majority of Syrians appreciate that the role of religion is to manage the relationship between the individual and God, but not the individual and the state. However, a small vocal and activist minority are intent on establishing an Islamic state.

The lack of a coherent and credible opposition further complicated matters. Except for the short- lived Damascus spring in the period 2000-2001, no effective internal opposition was allowed to emerge. In these circumstances, once the uprising erupted, an opposition emerged abroad. However, the majority of this external opposition quickly became subject to the influence of its regional and international backers. Thus, it was unable to articulate a clear and realistic national agenda that could find domestic resonance. Regrettably, the more realistic segments of such opposition failed to gain adequate regional and international support.

Regional and International Dynamics

If domestic drivers led to the 2011 uprising, it was foreign interventions which exacerbated the situation, transforming it into a full-fledged conflict and proxy war among regional and global rivals. There is a need, therefore, to analyze the factors that have caused these foreign interventions.

Syria is at the center of a region already replete with conflicts fueled by external interventions. It is also part of an Arab World which, regrettably, possesses no coherent vision of its common interests and, at the same time, lacks an effective regional mechanism for conflict resolution. This is primarily the result of a lack of leadership, largely arising from the dispersal of the sources of power—economic, political, military and ideological—among different countries.

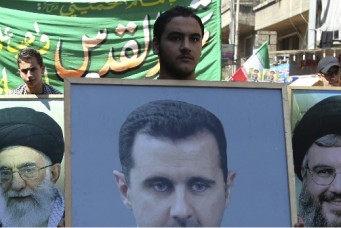

Under these conditions, the Gulf states were persuaded that the primary threat to their security was Iran and that regime change in Syria—Iran’s main ally in the region—was the best means to address this threat.

Meanwhile, the one Arab country that could have taken the initiative in finding a political solution—Egypt—was distracted by putting its house in order after the tumultuous events of the period 2011-2013.

Additionally, at this time, Turkey believed that dominating Syria was key to expanding its regional influence. This became all the more important when the Muslim Brotherhood, one of Turkey’s its main instruments used to spread influence in the region, was removed from power in Egypt in 2013. It therefore became imperative for Ankara to expand its influence to another key Arab country: Syria—chosen because Iraq was in chaos and Saudi Arabia was beyond reach because of its special relationship with Washington. Ankara initially reached out to Assad in an effort to convince him to cooperate in bringing about the change that would have propelled the Turkish client, the Muslim Brotherhood, into the circles of power in Damascus. However, Turkey quickly reversed course when it became obvious that Muslim Brotherhood rule in Egypt was coming to an end. A friendly regime in Damascus became all the more essential to furthering Turkey’s interests in the region as a means to enhance its international standing within the unfolding international order.

On the other hand, Israel, while facing no real direct threat from Syria since the 1974 Disengagement Agreement which stabilized the military situation on the Syrian Golan Heights after the 1973 War, was wary of the mounting influence of Tehran on its northern neighbor. Israel did not, however, view this as enough of a threat to warrant military action on its part. Once the conflict erupted, Israel was content that a Syria distracted by a protracted but contained internal conflict would further reduce a potentially critical threat to its security. No doubt the resulting increased Iranian military presence was a source of concern. But as the past few years have demonstrated, it was a threat that could be managed through selective aerial targeting of Iranian and Hezbollah military assets in Syria together with providing support to opposition armed groups across the border in the Golan Heights.

Iran also believed that threats to its security were more effectively addressed by confronting them outside its borders. This forward defense policy explains its expansionist and destabilizing regional policies. These policies were reflected in Iran’s work to ensure a friendly regime would rule in Damascus to protect its lifeline to Hezbollah, a key deterrent against its main adversary—Israel. In fact, Iran exploited vacuums resulting from mistakes committed by others, be that in Iraq, Syria, or Yemen, to further its regional agenda.

At the international level, the United States, having never considered Syria a priority, viewed the country from the dual perspectives of Israel’s security and the need to confront Iran. It was therefore satisfied to let its regional allies and friends—namely Israel, Turkey, and the Arab countries in the Gulf—to do its bidding. Initially, the U.S. military’s role was limited to providing arms and training to some groups of the Syrian armed opposition—a venture that proved to be only marginally effective, if not counterproductive, in some cases. Later on, U.S. involvement escalated to the occasional missile strike and rare air attack, paired with an extremely limited presence on the ground to protect the oil fields, and some patrols undertaken in loose coordination with the Russians to prevent confrontation between the Syrian and Turkish armies and the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). However, the overwhelming majority of U.S. military activities concentrated on providing intelligence, military operational planning, and logistical support to the SDF east of the Euphrates and maintaining a presence in the remote area of Tanf in southeastern Syria to block one of the supply lines used by Iran which runs from Iraq to western Syria. With this “at-an-arm’s length policy”, Washington forfeited any possibility to exercise serious influence over the evolution of the conflict.

It is also clear that, in 2011, both the European Union and the United States were convinced that Syria was the place to check and diminish Iranian influence in the Middle East. They reasoned that if one could find a way to peel Damascus away from Tehran then Iran’s influence in the Middle East would be largely reversed, or at least contained. Both the Europeans and the Americans concluded that this was only possible through regime change in Damascus, which they were convinced would take place in short order.

Meanwhile, Russia—which successfully utilized the conflict to further its global stature and regional interests—did not have the necessary instruments or regional and international influence to bring about a settlement. Initially aware of the nature of the Syrian regime and skeptical of the Arab Spring, Moscow was confident that Damascus would be able to handle the uprising, always reserving the option of military intervention to prevent the regime’s collapse. It was content to provide Damascus with the necessary military assistance and diplomatic cover in the UN Security Council. However, once the military situation appeared to turn against the government, Russia found the military intervention of Hezbollah and Iran a convenient arrangement that would spare it direct military action. Yet, in September 2015, when it appeared the Syrian regime was under serious threat, Moscow decided to intervene militarily. It was an intervention designed to minimize Russian fatalities and was therefore confined to air support, military operational planning, logistics, special operations, and intelligence. Actual combat was left to the Syrian army and its local militias with the support of Hezbollah and Iran and its militias.

To better understand Russia’s underlying motivations, one needs to take a few steps back to gain perspective. With the departure of Russian military advisors from Egypt in 1973, Moscow had lost its most important ally in the region. Since then, it has been trying to regain at least part of its influence. Additionally, with the demise of the Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq in 1993, losing Syria to an unfriendly government would have dealt Moscow a major strategic setback. The conflict in Syria, therefore, provided an opportunity that could not be missed. Syria was Moscow’s last ally in the region. Unlike the United States, it would not abandon its friends, thereby enhancing its credibility as a reliable friend and ally.

There was a need to prove that the Russian military had overcome its “Afghanistan Syndrome.” Moscow had not had direct military experience beyond its borders since its woeful experience in Afghanistan some thirty years earlier. The only other serious military experiences it had was the internal conflict in Chechnya from 1999-2009 and Transnistria (1992) and Georgia (2008), both of which took place just across the border. Syria also offered a rare opportunity to test new weapons as well as military techniques.

Additionally, Russia could not accept another Islamist regime close to its southern border in the Caucuses—Moscow’s soft underbelly with a Muslim majority susceptible to extremist influences from Damascus if it were to fall to Islamists. The presence of war hardened veterans from the Chechnya conflict, and other regions of Russia, and the former Soviet Union in Central Asia made the problem more urgent. Moscow’s strategy was to defeat them outside its border.

Moreover, the history of Russia’s relationship with both Turkey and Iran has been extremely complicated, and Syria acted as an arena to manage its complex relationships with both countries. Given the nature of these relationships, Syria offered Moscow additional leverage.

Neither Moscow nor Washington nor, for that matter, the EU, were prepared to “dirty their hands”. The United States and the EU allowed their friends and allies in the region to manage the situation on the ground. They then carefully escalated their intervention to meet the evolving situation, but always minimized direct military presence in the areas of operations. This was also true, to some extent, for the Russians who were content to leave Iran and its militias to do the actual combat.

In short, there were a host of regional and international players who seized the opportunity to enter the Syrian theatre to further their national interests. The uprising in 2011 and the brutal reaction of the government provided external actors an excuse to arm and fund armed groups opposed to the government (many of which turned out to be extremists or even terrorists) for “regime change”. It also provided the opportunity for the supporters of Damascus in Moscow and Tehran to increase their military presence and political influence in Syria.

Diplomatic Intervention and Progress

In such circumstances and with no agreement among local, regional, and international players on how to end the conflict, it was not surprising that the UN was unable to make progress toward a political settlement.

Member states, in particular members of the UN Security Council, already at odds with each other over the outcome of the Council’s decisions in Libya, were disappointing in their support of UN efforts. While they supported the UN-LAS joint envoy Kofi Anna’s proposals for de-escalation, after years of impasse over the interpretation of the 2012 Geneva Communiqué—which introduced transitional governance, review of the constitutional order, elections, and accountability—and the adoption of the 2015 Security Council Resolution 2254—which contains a road map for a political settlement—they have done little else in terms of pushing the Syrian protagonists to reach a settlement.

Successive UN Special Envoys could only depend on vague verbal support from the Security Council devoid of without specific guidance or concrete ideas. The Security Council, particularly after adopting Resolution 2254, was paralyzed by the lack of agreement among its members. However, the UN Special Envoys were able to produce ideas and initiatives as well as documents that have kept the political process alive—particularly 2017’s “Twelve Living Principles”. First introduced in 2016 and evolved until adopted by the Congress of the Syrian National Dialogue, in Sochi in January 2018, these principles define the principles upon which a future Syria could be based.

To set the record straight, Russia produced a number of initiatives, including a non-paper in the fall of 2015 on preliminary elements for a political settlement to coincide with the inception of the International Syria Support Group (ISSG). In 2017, through the Astana process, Iran, Russia and Turkey, together with the Syrian government and representatives of some of the Syrian opposition armed groups, created De-escalation Zones thereby helping to reduce the intensity of fighting. The Congress of the Syrian National Dialogue, held in Sochi in January 2018, ultimately produced the Syrian Constitutional Committee (SCC) in 2019 and adopted the “Twelve Living Principles”. Iran, on the other hand, proposed in October 2012 the “Six Point Plan” containing interesting ideas such as a transitional government to oversee presidential and parliamentary elections. Whether or not the purpose of these initiatives was merely to buy time in order to save the regime in Damascus and consolidate Moscow’s and Tehran’s military presence and political influence is a matter of debate.

China also made a number of proposals: two in 2012 and one, it appears, during its foreign minister’s July 2021 visit to Damascus. All three proposals, however, generally only contain uncontroversial principles for a settlement.

On the other hand, the United States did not independently initiate any ideas to advance the political settlement. It supported the initiatives proposed by both the Arab League, which ended with the withdrawal of Arab observers in January 2012, and the UN, which remain ongoing. U.S. cooperation with Russian produced the 2012 Geneva Communiqué and UN Security Council Resolutions 2254 (2015) and 2118 (2013)—on the removal of chemical weapons from Syria—all major landmarks in the political process. Likewise, the UK and France were content to in supporting Arab League and UN initiatives. Had these three countries generated new ideas, the prospects for a political settlement may have been greatly enhanced.

A standstill in the political process resulted. The only aspect of Resolution 2254 that gained traction was the creation of the Syrian Constitutional Committee in the fall of 2019. The SCC could have been created at least nine months earlier, at the end of 2018, however, due to disagreements between the United States, U.S. allies, and Russia, this was not the case. Interestingly, the United States fiercely resisted the creation of the SCC until December 2018, but reversed its position by the end of January 2019, likely to provide cover for President Trump’s December 2018 announcement which to withdrew U.S. troops from Syria. U.S. military disengagement needed to be justified by increased activity in the political process. At the time, the aspect of a this process that held the most promise was the Syrian Constitutional Committee.

Turkey’s position requires separate treatment. Caught between cooperating with Russia in the Astana process and its desire to influence the outcome of the political settlement separately, Ankara supported the creation of the SCC and, at the same time, undermined it. It supported the principle to appease Moscow, but at the same time, as the main sponsor of the opposition, interfered with its composition to ensure its allies in the opposition dominated the opposition delegation, and that the third delegation of neutrals, who represented civil society, did not harbor positions inimical to Turkish interests. To be fair, Damascus did the same. A composition far from ideal resulted, with an emphasis on political orientation rather than competence. It also delayed the inauguration of the SCC by at least nine months, resulting in a meeting held under less favorable conditions.

The situation persists to this day. The political process remains confined to the Syrian Constitutional Committee, which has made little headway since September 2019. On the one hand, the issues discussed are extremely complicated, and the SCC is being asked to resolve political issues which could not be resolved at negotiation held in the past eight years. On the other hand, half-hearted support, at best, from the United States and its allies for the UN’s facilitation of the SCC translated to lukewarm UN engagement in the process, appearing to some, at times, that every smallest disagreement or challenge is used to stall the work of the Committee.

In the meantime, the government in Damascus continues to operate according to the present constitution. Presidential elections were held in May, and in July, President Assad was sworn in for a fourth term. The external opposition remains beholden to the illusion that the regime in Damascus will be removed. Regional and international players are still unable to agree on how to bring about a settlement. Thus, the Syrian people continue to pay an increasingly heavy price.

Ambassador Ramzy Ezzeldin Ramzy served as the United Nations Assistant Secretary General and Deputy Special Envoy for Syria ( 2014-2019). Before that he served as Senior Under Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Egypt, Ambassador to Germany, Austria and Brazil. He also served as Permanent Representative to the United Nations and other international organizations in Vienna.

Read More