Time to Stop Talking of the Shiite-Sunni Divide

When Western media frames the Middle East in terms of sectarianism, not only does it do a grave disservice to its audience, but also to the people of this region, with far-reaching consequences

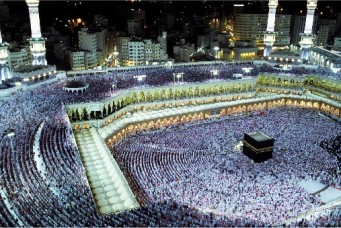

Iraqi Muslim worshippers shake hands during a joint Sunni-Shiite Friday prayer at the Martyrs Monument in Baghdad, May 24, 2013. Thaier al-Sudani/Reuters

Sensationalism, short attention spans, commercialism, and fake news are familiar tropes raised when discussing the problems of mass media. Yet another and more profound issue with mass media, articulated by scholars such as Niklas Luhmann, Ulrich Beck, and others, is its role in constructing the realities of its consumers, creating prisms through which people understand and relate to the facts around them. Mass media is no monolith; it presents competing, even contradictory, realities and prisms, but at times and for specific topics, it taps into the same reservoir of cultural, intellectual, and historical references. Through this, it constructs parallel realities and can privilege a single lens above all others. This is quite true of mainstream Western media and the “truths” it creates about Arab countries, Muslim societies, and Islam. The examples are many, and the case is well-established. One such reality that Western media imposes and presents to its consumers is to view conflicts in contemporary Arab and Muslim societies through the Sunni-Shiite divide, that is, they are mostly or mainly about sectarianism.

Most media outlets seek to present their audience with a simple, easy-to-understand reality, void of too much nuance or complexity. Thus, the insistence on the Sunni-Shiite prism should neither be surprising nor assumed to be intentionally biased. Reductionism is the inevitable collateral of the medium. Nevertheless, this reductionism obscures understanding of the region’s politics, leads to bad policy, and relieves Western powers from responsibility for the bloodbath in the region. The fallacies and danger inherent in this supposed reality and its associated prism must be raised and dealt with.

Sectarianism: A Straightforward Explanation

By and large, Western media offers a straightforward explanation of the complex and multi-layered factors shaping the region’s politics: that the Middle East is divided into Sunni and Shiite Muslims and that they had a dispute 1,400 years ago that continues to this day. Understanding the old dispute is required to understand contemporary disputes. Thus, the wars, conflicts, terrorism, and proliferation of militarized non-state actors in the Middle East, the Saudi-Iranian confrontation, the regional alliances, disputes, and security challenges in Bahrain, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen are all reduced to a 1,400-year-old schism.

To explain the post-war conflict in Iraq in 2014, the Washington Post presented a two-minute video tracing it back to the division of Muslims into Sunnis and Shiites centuries ago, as though little time had passed. The New York Times echoed this in 2016, presenting a map of the conflicts of the Middle East titled “Behind Stark Political Divisions, a More Complex Map of Sunnis and Shiites.” Thomas Friedman, a journalist with decades of coverage of the Middle East, reduces the complicated and multi-layered issues in the Yemeni conflict to “the 7th century struggle over who is the rightful heir to the Prophet Muhammad—Shiites or Sunnis.” Likewise, The Wall Street Journal points its readers to the theological differences between Sunnis and Shiites to help them understand regional politics, asserting in 2016 that, “While the dispute appears politically grounded, it also derives from Islam’s central ideological division.”

After the resignation of Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Al-Harriri in November 2017, media outlets quickly framed the crisis as one between the Sunni Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Shiite Republic of Iran. Political analysis of Middle Eastern affairs almost always starts by highlighting the existence of Sunni states whose natural position is to be against Shiite states and proceeds from thereon.

It is not just the media. The Council on Foreign Relations once came to a similar conclusion: “An ancient religious divide is helping fuel a resurgence of conflicts in the Middle East and Muslim countries. Struggles between Sunni and Shiite forces have fed a Syrian civil war that threatens to transform the map of the Middle East, spurred violence that is fracturing Iraq, and widened fissures in a number of tense Gulf countries. Growing sectarian clashes have also sparked a revival of transnational jihadi networks that poses a threat beyond the region.” And it seems that there is a continuous feedback loop between Western media and Western think tanks, leading to the persistence of this oversimplified version of reality and method of analysis. There are critics of the Sunni-Shiite prism who have described it as “cringe-worthy”, simplistic, misleading, and lazy, and have presented more realistic approaches to understanding regional conflicts, analyzing them as one would analyze disputes elsewhere, that is, by considering political and economic factors such as oppression, injustice, discrimination, unequal access to opportunities and resources, incompatible territorial claims, among others. But such critique is mainly found among scholars and researchers, and while some are reaching mainstream media, it is not enough to break the iron grip of the sectarian narrative.

Sectarian Narratives: A Dangerous Self-fulfilling Prophecy

Niklas Luhmann, German sociologist and philosopher, stated, “Whatever we know about our society, or indeed about the world in which we live, we know through the mass media.” This is as true of politicians and policymakers as it is for average citizens. In his 2016 State of the Union Address, President Barack Obama—after pointing to the intelligence briefings as his source of information—said: “The Middle East is going through a transformation that will play out for a generation, rooted in conflicts that date back millennia.” A fundamental problem with the Sunni-Shiite prism is that key Western policymakers of the Middle East adopted it, overlooking all the complexities of current social and political affairs, the dynamics of alliance building and power balancing, relying instead on the simple Sunni-Shiites dichotomy. In Iraq, such a view came to play with destructive consequences in 2003. The U.S.-led invading coalition saw Iraq through a Sunni-Shiite prism and subsequently created the conditions for the devolution of existing religious differences into hard-set sectarian identities. The U.S.-led coalition decided to divide the Iraqi Governing Council seats based on Iraq’s religious differences, leading to a formalization of sectarianism. One story from journalist Dahr Jamail encapsulates this process, where a foreign power imposed its views on local actors with a devastating consequence:

“Back in December 2003 Sheikh Adnan, a Friday speaker at his mosque, had recounted a recent experience to me. During the first weeks of the occupation, a U.S. military commander had showed up in Baquba, the capital of Diyala province located roughly twenty-five miles northeast of Baghdad with a mixed Sunni-Shiite population. He had asked to meet with all the tribal and religious leaders. On the appointed day the assembled leaders were perplexed when the commander instructed them to divide themselves, Shiite on one side of the room, Sunni on the other.”

This action, which stemmed from an American-enforced “sectarian apportionment system”, was based on a skewed understanding of the social reality of the communities. It, and others like it, led to a formalization and institutionalization of sectarian identities, linked access to resources and power to one’s sectarian affiliation, developed sect-based polarization and discrimination, consolidated a dysfunctional political system, and challenged the sense of Iraqi nationalism, leading to violence and fragmentation of the state and society.

What the American-led coalition did in Iraq was done by other colonial powers in the past. In Rwanda, Hutu and Tutsi differences devolved into hardened ethnic identities due to Belgium empowering one over the other. This foreign-made category became fundamental to the Rwandans and shaped their distribution of power and wealth, ultimately leading to the civil war and the ensuing genocide. In other places, such as Lebanon, it was the Ottoman Empire and European colonialism, as scholar and author Ussama Makdisi has elaborately demonstrated. This issue is not merely about media inaccuracy, but about the media nourishing and sustaining a narrative with material consequences on the region.

Why the Shiite-Sunni Prism Is Wrong

To begin with, there has never been a Sunni-Shiite war in Islam’s 1,400-year history, and certainly not in recent memory. Of the two cases usually conjured in this context— the Salahuddin-Fatimid wars in the 12th century and the Ottoman-Safavid wars in the 16th/17th century, (where the former were “Sunnis” and the latter “Shiites”)—the Sunni-Shiite prism has been imposed on them by contemporary political and cultural actors. They can more accurately be read as a competition between strongmen, Christians, and Muslims, over control of Egypt’s riches in the case of the former conflict (which ended the Fatimid empire), and great power competition between the expanding Ottoman and Safavid empires in the case of the latter. Even if we were to find a war driven by a Sunni-Shiite divide in some corner of history, it would be wrong to claim that it has any contemporary relevance. There is no such thing as a collective Sunni-Shiite memory of conflict. There are no significant historical memories of hatred or fear between Sunnis and Shiites. Moreover, Sunnism and Shiism have never been considered national identities, and Sunnis and Shiites never considered themselves or each other in terms of nations.

There is no doubt that some version of this narrative exists in that some individuals consider themselves Sunni/Shiite, some speak ill of the other, and hate or exhibit animosity based on that difference. But there is no homogeneity among Sunnis nor among Shiites. Sunnism or Shiism does not entail any sense of group identity, nor does it lead to group loyalty, nor define roles and expectations between Shiites or between Sunnis—all of which are necessities for sectarian conflicts. There are simply none of the critical components and pre-conditions of sectarianism in the Middle East. Sunnism/Shiism are, of course, important to individuals who subscribe to them. But they are one value among others, such as class, ethnic, cultural, historical, regional, and ideological identities.

The problem is not that the media claims that Sunnism and Shiism matter. They do. The problem is when the media overlooks and obscures the multiple identities, affiliations, class differences, and the inherent diversity of the individuals subsumed in this religious affiliation. It is when the media assumes the existence of monolithic groups whose members are somewhat equal in their commitment to the group and its founding theology. All Shiites/Sunnis, according to the media narrative, adhere to and equally understand their respective theology and prioritize theological commitment in determining their social and political interests. This is false. Sunnism and Shiism matter but not in the ways the Sunni-Shiite prism assumes.

When Western media considers relations between a Sunni and Shiite majority country, it discounts the nationalities, the different cultures, historical memories, and the economic and security interests within the different countries, as well as their regional and international alliances, thereby reducing the whole relationship to Sunnism and Shiism. This reductionism simplifies, distorts, and obscures our understanding.

This is surprising considering the historical relations between so-called Sunni states and Shiite states. During the Iran–Iraq war, Iraqi Shiites were ardently opposed to Iran. Iran supported Christian Armenia in its war against the predominantly Shiite Azerbaijan. Saudi Arabia supported the “Shiite” Royalists in Yemen’s 1962-1970 civil war against the “Sunni” Egyptian intervention. The crisis in the Gulf Cooperation Council between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt on the one hand, and Qatar on the other was a telling example. Four “Sunni” states turn against another Sunni state, which then turns toward a Sunni state— Turkey—and a Shiite state—Iran—and finds support. The relationship between Iran, Turkey, and Iraq challenges Sunni-Shiite prisms. Such examples, of which more exist, demonstrate that material strategic interests define states’ positions, not religion or sect. The very notion of a Sunni/Shiite state is, therefore, useless.

The Sunni-Shiite Divide Is Always Local

This is not to claim that a Sunni-Shiite divide is non-existent in the region. There are Sunni-Shiite tensions, even conflicts, within some Arab countries, but they have little to no regional consequence. Sunni-Shiite tensions and conflicts in the communities of Bahrain, Iraq, Lebanon, or Syria do not imply nor mean Sunni-Shiite conflicts between the countries of the region. Sectarianism may be an internal problem for some countries, but it is not a regional problem. And if one must use Sunni/Shiite as terms of analysis, one should consistently localize them. A Lebanese Shiite or Sunni is Lebanese first and foremost. Their interests are primarily constructed by the structure of Lebanese socio-politics and economy; thus, their social/political/economic decisions primarily stem from that local Lebanese structure.

This also applies to the relationships between parties such as the Lebanese Hezbollah and Iraq’s Hashd Al-Shaabi with Iran. The foundation of those relationships is not a common theology of Shiism, but rather the opportunism, pragmatism, and realpolitik of local actors that leverage external support to further their own agenda, be it ideological—such as anti-American hegemony, anti-Israel, Islamism—or political or economic. Being Shiite is secondary in the foundations of those relationships, which explains why other Shiite movements and parties have had different relationships with Iran due to a different calculus, why relationships exist between Iran and “Sunni” Palestinian resistance movements, and why contention exists between many Arab “Shiite” political actors and Iran. Sectarianism must always be localized and rarely used in regional analysis, and even then, should be problematized and used only very carefully. To speak of a Sunni bloc that stretches from the western coasts of North Africa to the Eastern coasts of Indonesia, or a regional Shiite alliance, is baseless.

Time to Stop Talking of the Sunni-Shiite Divide

The Sunni-Shiite prism is a confused concept without a precise definition and is thus unqualified to be a helpful tool. It creates more obscurity than clarity and has led to mistakes with tragic human consequences, as in Iraq after 2003. Yet it is still used over and over again. Some scholars, such as Fanar Haddad in his excellent analysis of the Iraqi Sunni-Shiite context, suggest that we not drop the sectarian prism despite its lack of definition, but rather use it between quotation marks “followed by the appropriate suffix: sectarian hate, sectarian unity, sectarian discrimination….” His suggestion is helpful in an academic context, where there is room for nuance and high-level abstraction. But in media analysis of politics, interests, identity, distribution of power, competition, and conflict in the Middle East, such a term is an unneeded distraction and distortion. We are better off dropping it and disregarding any coverage that uses sectarianism, Shiism, and Sunnism. We should reject all narratives that present contemporary regional conflicts as rooted in ancient hatreds, historical grievances, or collective Sunni-Shiite memories.

Abdullah Hamidaddin is a senior research fellow and director of the Yemen Program at King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies. He is the author of Tweeted Heresies: Saudi Islam in Transformation, and editor of The Huthi Movement in Yemen: Ideology, Ambition and Security in the Arab Gulf. He has written articles and papers on Yemen and the geopolitics of the Arab Gulf region.