A Palestinian Outlet to the World, A Path toward Peace? Considerations and Options for a Gaza Seaport

Between economic considerations, intra-Palestinian divisions, and Israeli security concerns, there are a number of challenges facing the building of a seaport in Gaza, or in its alternatives. Nevertheless, it may be an opportunity to establish a tri-state free trade zone, and, ultimately, peace.

A Palestinian fishermen disembarks from a boat after returning from fishing at the seaport of Gaza City September 26, 2016. Picture taken September 26, 2016. REUTERS/Mohammed Salem – S1BEUDSINIAB

On September 12, 2021, at Israel’s Reichman University, then-Foreign Minister and current Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid presented his vision for a long-term settlement between Israel and the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip. Lapid’s plan— dubbed “Economy for Security”—outlined two stages: the first addressing the immediate humanitarian crisis in Gaza, and the second outlining a comprehensive development plan for Gaza, at the center of which was constructing a new Gazan seaport and providing a transportation link between Gaza and the West Bank.

Movement and access of people and goods into and out of Gaza has been an important topic in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations for decades. Establishing and providing access to a maritime trade hub would represent a major step toward expanding the Gazan and the overall Palestinian economy. However, to date, security, political, and economic barriers have prevented the development of such a port. A variety of models for this idea have been proposed, but none have been realized.

Any future effort to develop a Palestinian port will need to consider several factors: Palestinian national aspirations, Israeli security, institutional cooperation, costs, and location, among others. A port for Gaza has significant potential for good—expanding opportunities and building trust—but it is in all parties’ long-term interest for policymakers to be rigorous and methodical in evaluating options. This article examines the historical background of the Gaza seaport idea, the port’s treatment in the Oslo Accords and subsequent Israeli-Palestinian understandings, and reviews the main alternatives for developing a Palestinian seaport. It also identifies an optimal solution that maximizes the main actors’ preferences and that is worth consideration as policymakers seek fresh ideas to improve lives and rebuild confidence between Palestinians and Israelis.

Gaza has never had its own commercial cargo seaport, historically only accessing the sea through a small fishing port in Gaza City. Fishing has long been a central part of the Gazan economy, and Gaza City’s port is primarily used for fishing boats. Gaza’s port is shallow (about 5 meters, or 16 feet, deep) and lacks the docks, cranes, and warehouses necessary for handling modern cargo ships. With these limitations, virtually all goods that enter Gaza arrive over land from Israel and Egypt.

Prior to the Israeli occupation in the 1967 Six Day War, Gaza was administered by Egypt and all its foreign trade moved through Egyptian ports. After 1967, Gazan foreign trade shifted to Israeli ports, primarily Ashdod. Since 1994—following the Oslo Accords and establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA)—Gazan exports and imports have relied on Israeli ports, usually moving through the Karni border crossing in north Gaza. The Egyptian seaports of El-Arish and Port Said have also been used to import and export a smaller volume of goods through the Rafah crossing on Gaza’s southern border.

A Palestinian Seaport in the Oslo Accords and Subsequent Negotiations

A seaport for Gaza was low on the agenda during the 1993 Israeli-Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) negotiations in Oslo, which ultimately resulted in the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements (DOP). The DOP did not address the construction of a seaport in Gaza during the envisioned five-year transitional period of Palestinian autonomy. Instead, it simply stated that, along with several other organizations, “upon its inauguration, the [Palestinian] Council will establish…a Gaza Sea Port Authority” (DOP, Art. VII.4), and that a joint Israeli-Palestinian Continuing Committee for Economic Cooperation would “define guidelines for the establishment of a Gaza Sea Port Area” (DOP, Annex III, Art. 5). The parties recognized that building a seaport for Gaza would require significant investment and a construction timeline far beyond the five-year transitional period.

In negotiating the first Oslo implementation agreement—the 1994 Gaza-Jericho Agreement—the parties again pushed the issue to a later date, stating that until the construction of a Gaza seaport, “entry and exit of vessels, passengers and goods by sea would be through Israeli ports” (Art. XI.4.c.). The 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and Gaza, also known as “Oslo II” (the “Interim Agreement”) repeated verbatim the provisions of the Gaza-Jericho Agreement regarding a Gaza seaport (Interim Agreement, Annex II, Art. XIV.4). In sum, while the Oslo Accords reflected a Palestinian aspiration for developing a seaport in Gaza, they recognized that until it is constructed, Gaza would need to continue using Israeli (or Egyptian) seaports.

In October 1998, in the Wye River Memorandum, the parties again acknowledged the importance to the Palestinians of building a seaport in Gaza and committed themselves to quickly concluding an agreement regarding the construction of this port (Id. Art. III.4.). And finally, on September 4, 1999—four months after the contemplated end of the five-year transitional period and target date for concluding a permanent status agreement—the parties signed the Sharm El-Sheikh Memorandum, with detailed provisions regarding establishing a Gaza seaport. According to these provisions, construction of the Gaza seaport would begin on October 1, 1999, and once completed, the port would operate pursuant to the Interim Agreement, including its provisions related to customs, subject to the conclusion of a detailed, joint protocol regarding port operations, including security arrangements (Id., Section 6).

Following the unsuccessful Camp David summit in July 2000, Yasser Arafat’s PA— without coordination with Israel—began constructing a new seaport, using funds provided by the international community. The selected port site was near Nuseirat, about 5 km (3 miles) south of the existing fishing port in Gaza City. Subsequently, the PA agreed to negotiate with Israel, and on September 20, 2000, reached a detailed agreement called “Gaza Seaport Construction Understanding,” enabling construction to move forward with the aim of completing the port within eighteen months. A few days later, however, the second Intifada (also known as the “al Aqsa Intifada”) began, an outbreak of violence which lasted more than four years and led to the deaths of thousands of Israelis and Palestinians. During the fighting, Israel bombed the Gaza port construction site, destroying it.

In September 2005, after four years of violence and seeing no prospect for a comprehensive Israeli-Palestinian peace settlement, Israel unilaterally withdrew its military forces and civilian settlements from Gaza. Weeks later, on November 15, 2005, Israel and the PA entered into an “Agreement on Movement and Access,” which stated that the construction of a Gaza seaport may commence, and that Israel would not interfere with its operations. The agreement also stated that the two parties and the United States would establish a tripartite committee to develop security and other arrangements for the port prior to its opening (Id., Section 5).

However, in June 2007, before the construction of a Gaza seaport resumed, Hamas wrested control of Gaza from the PA. Because Hamas recognized neither Israel nor the Oslo Accords, all agreements and plans regarding the Gaza seaport were suspended. Because of Hamas’ hostility to Israel and its attempts to smuggle arms into Gaza, Israel and Egypt have since 2007 monitored and controlled the movement of goods and people across Gaza’s borders.

Considerations for a Future Gaza Seaport

The future of a seaport for Gaza remains unclear, but proposals like Prime Minister Lapid’s may be back on the table. In considering the location and operations of a future Gazan seaport, four factors must be evaluated: Israeli security; Palestinian national aspirations; safe passage between Gaza and the West Bank; and the current status of the divide between the PA-controlled West Bank and the Hamas-controlled Gaza.

Israeli Security

Israel’s primary security concern regarding a Gaza seaport is preventing the movement through it of terrorists, weapons, and explosives. The Oslo Accords included provisions for Israeli security personnel to participate, alongside PA officials, in inspecting passengers and goods crossing through all Palestinian land and sea borders. Pursuant to these provisions, Israeli security personnel operated at crossings between the Palestinian Territories and Israel, as well as all land crossings between the West Bank and Jordan and the crossing point between Gaza and Egypt.

The 2005 “Agreement on Movement and Access,” which was signed between Israel and the PA and followed the Israeli disengagement from Gaza, included principles for operating the land border crossings between Egypt and Gaza. After Hamas took over Gaza from the PA, important components of this agreement fell apart—notably the PA-Israel-Egypt partnership at the Kerem Shalom border crossing and European Union assistance in inspecting goods at the Rafah crossing. For many years after Hamas’ takeover of Gaza, Egypt imposed severe restrictions on the transit of goods and people at the Rafah border crossing, some of which have been lifted in recent years. In 2009, following an intense round of fighting between Israel and Hamas (Operation Cast Lead), Israel imposed a naval blockade on Gaza, extending twenty nautical miles into the sea. Since that time, all vessels carrying goods or passengers to Gaza are required to offload them for inspection in Egyptian or Israeli seaports, from where they are transported to Gaza by land.

As long as Hamas controls Gaza, it is hard to imagine an Israeli sign-off on a seaport inside Gaza, which would prevent inspections by Israeli, PA, or acceptable third-party security personnel. Thus, Israeli security considerations mandate that the inspection of incoming cargo and passengers be conducted outside Gaza.

Palestinian National Aspirations

National aspirations drive a Palestinian desire to have a seaport inside Gaza managed and operated exclusively by Palestinians, free of any Israeli control. The Palestinians consider a free Palestinian seaport a critical symbol of sovereignty and independence. However, Hamas’ control of Gaza complicates matters. Unlike the PLO, Hamas does not accept the Oslo Accords, including their security provisions, and its hostility to Israel would certainly preclude any role inside Gaza for Israeli supervision on the movement of goods and people to and from the Strip. Hamas’ control of Gaza would likely also make impossible the operation inside the Strip of third-party inspectors that are acceptable to Israel. This likely outcome was demonstrated when, following the unilateral redeployment of Israel from Gaza, arrangements were made between Israel and the PA where the Rafah land crossing, located on the border between Egypt and Gaza, would be operated by the PA under the supervision of a third-party—the European Union Border Assistance Mission Rafah (EUBAMR). After the Hamas takeover, however, the PA could not guarantee the safety of the EUBAMR observers, and they left.

West Bank-Gaza Safe Passage

The seaport envisioned for Gaza in the Oslo Accords was intended to serve the Palestinian Territories as a whole—the Gaza Strip (365 square km or 141 square miles) and the much larger, but landlocked, West Bank (5,655 square km or 2,183 square miles). The Oslo Accords expected arrangements to be made for safe passage between the West Bank and Gaza through Israel, subject only to Israel’s security considerations. Thus far, however, the parties have failed to negotiate a safe-passage arrangement. Going forward, planning for a Gaza seaport, especially its location and capacities, must take into consideration a safe passage regime between Gaza and the West Bank which would facilitate direct movement of goods.

Intra-Palestinian Divisions

The Gaza-West Bank divide makes most components of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict more challenging, not least of all efforts at economic development. More specifically, Hamas’ control of Gaza since 2007, its non-recognition of Israel and the PA, and its rejection of all Israeli-Palestinian agreements have been barriers to development. In the case of a Gaza seaport, without reunification of the West Bank and Gaza under a single government which abides by past agreements, numerous questions emerge around the operations of the port, the population it will serve, and the governmental authority that will be responsible for running it.

One possibility is to delay any further planning of a Gaza seaport until the fundamental issues around the Israel-PA-Hamas triangle have been resolved. Another, perhaps better, option is to begin the planning process, using it as a catalyst for incrementally resolving the more fundamental issues, while also alleviating the dire humanitarian conditions faced by the two million residents of Gaza.

Alternatives for a Gaza Seaport

In 2016, a group of American and Israeli experts in ports, shipping, economics, security, and Middle East affairs conducted a comprehensive study of options for providing the Palestinians with a seaport. (See Figure 1 for the main alternative locations proposed for the port.) The study identified several options for a Palestinian seaport, which can be grouped along two sets of criteria—location and size:

1) An autonomous Palestinian pier (that is, a dedicated Palestinian section within

an existing or a future port) vs. a new, separate Palestinian port.

2) A major port designed to handle large ships and volumes of cargo vs. a small port, designed to handle small ships and cargo volumes.

There are a number of options for the parties to consider in seeking to build a Palestinian seaport, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Among the primary options are: 1) continuance of the status quo where Palestinian foreign trade is accomplished through Israel’s and Egypt’s seaports; 2) establishing a Palestinian pier in Israel’s Ashdod Port; 3) building a seaport in Gaza; 4) constructing an island off Gaza’s coast that will serve as a port; 5) establishing a Palestinian pier in Cyprus’s Larnaca Port; 6) establishing a Palestinian pier in Egypt’s El-Arish Port. But it is the final option, Option 7—proposing the construction of a port for Gaza on Egyptian territory adjacent to the Strip’s border—which may hold the most promise.

Figure 1: Alternative Port Options

Option 1: Continue the Status Quo, Using Israeli Seaports for Palestinian Cargoes

Today, most foreign cargo destined for Gaza is shipped to Ashdod and trucked 90 km (56 miles) to the Kerem Shalom Border Crossing, located on the border junction between Egypt, Gaza, and Israel at the southern tip of Gaza. At Kerem Shalom, Israel has constructed a vast and sophisticated terminal on about 50 hectares (123.5 acres), with high-wall inspection cells, steel gates, and surveillance towers. The imported cargo is unloaded from Israeli trucks and inspected by Israeli inspectors. The cleared cargo is then loaded onto secured Gazan trucks and moved through steel gates across the border into a Hamas-controlled Palestinian inspection terminal. Gazan exports follow a similar process, but in the opposite direction.

Despite tense Israeli-Hamas relations, over the years a close operational cooperation between the Kerem Shalom terminals has developed. Special “sterilized” trucks— which do not leave the compound, thus limiting any threat from the outside—move the goods back and forth between terminals. While Hamas controls the Palestinian terminal, PA representatives are also present in the terminal and observe the process. The PA—in coordination with Israel—also issues all export and import licenses related to Gaza (as it does for West Bank licenses), and—in accordance with the 1994 Israel-PLO Paris Protocol—it informs Israel of each import request. From the standpoint of Israel’s security interest, the status quo is perhaps the optimal option. Existing Israeli ports can easily continue to accommodate the Gazan foreign trade, which accounts for only 5 percent of Israel’s overall trade. Israel has recently inaugurated two new, modern ports which double the overall capacity of Israel’s port system, allowing it to handle all Israeli and Palestinian foreign trade for many years to come. The current Israel-PA-Hamas operation at Kerem Shalom is quite efficient, processing about 1,000 trucks daily. The present system satisfies Israel’s security concerns and is not dependent on developing West Bank-Gaza safe passage arrangements since West Bank goods are trucked directly to and from Israeli ports. However, the overall Ashdod/Kerem-Shalom/Gaza process is long and costly due to the relatively high labor cost in Israel and the 90 km (56 miles) of trucking required between Ashdod and Kerem Shalom. Importantly, this option also does not meet Palestinian national aspirations for a Palestinian-controlled port.

Option 2: Designate an Autonomous Palestinian Section Inside the Ashdod Port

If the parties were to seek to build on the current system while providing for more Palestinian responsibility in handling port operations, they could negotiate a “Palestinian Pier” at the Ashdod Port. In such an arrangement, a dedicated section of the Ashdod Port would be leased to the PA for a long term (e.g., 99 years). The Palestinian section could include 2-3 berths, storage sheds, and a gate (collectively, a “pier”). The PA would be responsible for the operations of the pier and would collect port dues. The PA would employ Palestinian labor, which, like many other West Bank and Gaza Palestinians already employed inside Israel, would be bussed daily (or weekly) from the West Bank and Gaza. Israel would remain responsible for overall security, including inspection of imported goods. The transfer of cargo between Ashdod and Kerem Shalom would be carried out by Israeli-approved Palestinian drivers and trucks. Limited, additional inspection would be conducted at the Kerem Shalom Border Crossing.

To the Palestinians, this option partially satisfies their national aspirations, creates more Palestinian-held jobs, and provides for savings in costs of port handling, trucking, and inspection, as all such services would be provided by lower-cost Palestinian labor. Further, the need for investments is also minimal. For Israel, this option poses some security risks, as Israel would be ceding a degree of control over the import-export process and—by granting Palestinian access to Israel—may be raising risks in Israeli civilian spaces and security areas, such as at the Israeli Naval Base in Ashdod.

Option 3: Develop a New Palestinian Seaport in Gaza

A third option is the construction of a new seaport in Gaza, operated by Palestinians. The port would presumably be located at the Gaza City/Nuseirat location. A rough cost estimate for constructing such a port is $300–400 million.

A new port in Gaza would meet all Palestinian requirements, serving as a symbol of Palestinian sovereignty and self-reliance. However, this option is also one of the most expensive and politically complex. As of this writing, there seems little chance for the parties to achieve the degree of progress in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict necessary to make a Palestinian port in Gaza feasible. Israel’s position remains that it must retain the ability to inspect—directly or through an acceptable third party—all imports to Gaza, which cannot be done if the port is located inside Gaza. Furthermore, the current proposed site at the Gaza City/Nuseirat location is cordoned by densely populated refugee camps, making land access difficult and limiting the availability of nearby areas for necessary port-related development, rendering this option impractical.

Option 4: Build a Palestinian Port on an Artificial Island Off the Coast of Gaza

In 2011, former Israeli Minister of Transportation Israel Katz proposed that a large, 8 sq km (3 sq mile) artificial island be constructed off the coast of Gaza, with a port for the Palestinian Territories. This island would be connected to the shore by a 4.5 km

(2.8 mile) fixed bridge with a drawbridge section able to cut-off the port in case of a security emergency. Under this proposal, the inspection of trucks and cargoes would be conducted on the bridge by international inspectors. Additionally, Katz proposed that the island would also accommodate a Palestinian airport, a power generation plant, a desalination plant, and a marina. As indicated earlier, Prime Minister Lapid recently adopted this plan.

For Palestinians, this option provides the advantage of a seaport in Gaza, but with more operational difficulties due to limited access through a single bridge. The Palestinians would forgo some sovereignty in the process due to international inspections, but Israel would likely find this option more acceptable than a port in the Strip. However attractive, this option carries a huge cost, estimated at $5-10 billion with a construction time of five to ten years. The island is also likely to adversely impact Gaza’s and Israel’s coastline, creating considerable resistance from environmentalists.

Option 5: Dedicate a Section for Palestinian Use in Cyprus’s Larnaca Seaport

In 2018, former Israeli Minister of Defense (currently Israel’s Minister of Finance) Avigdor Lieberman proposed his own solution: that Gaza-destined cargo be discharged from foreign ships at a dedicated section in the Port of Larnaca, Cyprus. Once there, cargo would be inspected by Israeli officials and reloaded onto small Gazan cargo ships sailing to the existing Gaza fishing port (or a new Palestinian port to be built in Gaza), with Israeli Navy escort. The Cypriot Government expressed interest in this idea, in part because of the jobs it would create for Cypriots.

This option allows for Israeli security inspection of Gaza-destined goods, and for Palestinians it allows for the development of the existing fishing port of Gaza, turning it into a cargo port. The disadvantage, however, would be the additional costs of double-handling and additional shipment distance between Cyprus and Gaza. Further, the potential expansion of the fishing pier located in front of Gaza City is quite limited.

Option 6: Use the Egyptian El-Arish Seaport for Palestinian Foreign Trade

The Palestinians could also seek to use a section of an Egyptian seaport—El-Arish— under a long-term (e.g., 99 years) land lease. This follows a common worldwide practice in which coastal countries provide landlocked neighbors with autonomous ports (e.g.,

Tanzania/Zambia, Peru/Bolivia, and Uruguay/Paraguay).

This option is similar to the proposal for a Palestinian section in Israel’s Ashdod Port—mirroring Option 2 above—but would be accomplished through Egypt rather than Israel. It could be developed as part of a forthcoming expansion of the El-Arish Port planned by the Egyptian government. From El-Arish, Gaza-destined imports would be trucked to the Kerem Shalom Crossing Point, with exports moving in the opposite direction. As in Option 2, the PA would be responsible for the operations of the Palestinian pier in El-Arish and would collect port dues. The PA would employ Palestinian workers, who would be bussed in daily from Gaza. Egypt would be responsible for security, including inspection of imports and exports.

The primary difference between this option and Option 2 is capacity: Egypt’s El-Arish Port is much smaller than Israel’s Ashdod Port and currently cannot accommodate an autonomous Palestinian section. This alternative, therefore, can be applied only when the new El-Arish Port, still in early planning, is built. The new port, estimated by Egypt to cost $1.3 billion, will probably take five years to construct. Further, trucking Gazan cargoes 45 km (28 miles) on Egyptian roads may require special arrangements in terms of licensing trucks and drivers and providing Egyptian security along the route.

Option 7: Build an Autonomous Palestinian Seaport on the South Gazan Border

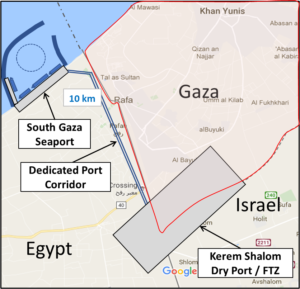

Finally, access to a seaport for the Palestinians can be achieved through the construction of a new, autonomous “South Gaza Port” on Egyptian territory adjacent to the Gazan border, consisting only of ship-handling facilities. The cargo would be transported from ships directly to the Kerem Shalom Crossing, which would be expanded to become a “dry” port, providing all the services of a seaport except for loading/unloading ships. A 10-km (6.2 mile) road connecting the seaport to the dry port would be constructed in the half-kilometer-wide (one-third of a mile) Egyptian security zone that runs along Gaza’s southern border. Figure 2 illustrates the seaport/ dry-port concept proposed for the South Gaza Port plan.

This conceptual port would be relatively small—requiring only the capacity to meet Palestinian import/export needs—including a breakwater, three berths, and a 650-meter (2,132 foot) dock with 12 meters (39 feet) of water depth alongside. Such a port would cost an estimated $200-250 million and take two to three years to complete, including planning. The autonomous South Gaza Port would be managed and operated by Palestinians, including the trucking to Kerem Shalom. If found more desirable by Egypt, the actual port concession could be granted to a Global Port Operator, which, in turn, would contract with the PA, Hamas, or both. Granting a concession to such an operator is a common worldwide practice, currently in use by both Egypt and Israel.

For Palestinians, the primary advantage of this port is location: for all practical purposes the port would function as if it is in Gaza, despite being just outside the Gaza Strip. To facilitate operations, this port could have a special nearby border crossing to allow easy access to Gazan employees. The port location, 10 km (6.2 miles) away from Kerem Shalom, would also provide significant savings in land transportation costs compared to the 45 km (28 miles) distance of the El-Arish Palestinian Pier and the 90 km distance to Ashdod. This option also satisfies Israeli and Egyptian security concerns, as the proven Kerem Shalom Crossing Point operations would be maintained. Egypt would also benefit from the payments by the port operator for leasing the port site and using the intra-port road, and from fees charged for ship services (such as pilotage, towage, and channel fees) and peripheral security services.

Figure 2: The South Gaza Seaport Plan

An Opportunity to Think Bigger: The Case for a Tri-State Free Trade Zone

None of the options reviewed above can satisfy all the opposing requirements and concerns of the Palestinians (sovereignty) and Israelis/Egyptians (security). Israel and Egypt are not likely to agree to a Palestinian port inside Gaza, and the Palestinians will not be satisfied with a port outside Gaza. However, it seems that the South Gaza Port option could be the compromise most acceptable for all sides. For the Palestinians, its location outside of Israel and as close as possible to Gaza makes it the best option outside of the Strip. For Israel, retaining the current system of inspections at Kerem Shalom should satisfy Israeli security concerns. For Egypt, constructing a port on its sovereign territory would generate substantial economic benefits and pose almost no risk. Another advantage of the South Gaza option is its practicality in terms of investment and construction time, especially when contrasted with the artificial island and El-Arish port options.

The development of a port for Gaza along the South Gaza Port plan has potential far exceeding the logistical savings in moving goods. The port project could be an important “confidence building measure,” expanding trust and cooperation among the PA, Hamas, Israel, and Egypt, while also relieving some of Gaza’s economic stress. It may also be a powerful incentive for Hamas to maintain calm—or perhaps a disincentive to launch attacks which might disrupt the Gazan economy. Such a step may fit into the Bennett-Lapid government’s commitment to “shrinking the conflict”.

Further, taking advantage of the nearby seaport, the expanded Kerem Shalom could become the logistical and industrial hub of Gaza (indeed all the Palestinian Territories), which could attract export/import-related activities. Kerem Shalom is located at Gaza’s widest and least populated point, where land for industrial development is still available and where Israel could consider land-swaps as a part of future Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. Moreover, due to Kerem Shalom’s strategic location at the meeting point of Gaza, Egypt, and Israel, it could be declared a tri-state Free Trade Zone (FTZ). A future Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement is likely to diffuse many of the parties’ security concerns and facilitate an uninterrupted flow of trade among these countries.

Kerem Shalom could also be connected to the Israeli rail system which, in turn, could be extended to the West Bank, providing safe passage between the South Gaza Port, Kerem Shalom dry port/FTZ complex (and Gaza, more generally) and the West Bank. Eventually, should Kerem Shalom be integrated into the Egyptian rail system, it could become the hub of a regional transportation system. Additionally, the Kerem Shalom FTZ could be expanded into Egypt, generating employment opportunities for Egyptian residents of North Sinai. Moreover, qualifying Egyptian products manufactured in the FTZ (in addition to qualifying Palestinian products) could be imported free of customs duties to the United States under the American Qualifying Industrial Zone (QIZ) Initiative adopted in 1996 to support the peace process in the Middle East. However distant a comprehensive negotiated peace may seem, the ripple effects of peace could be momentous. Developing the infrastructure and institutions to prepare for that day can be a step toward making that potential a reality.

While plenty of obstacles remain, the years ahead may be an opportune time to revisit options for developing a Gazan port. Policymakers on all sides should not delay discussion around a Gaza seaport until the conflict’s fundamental issues have been resolved. Rather, weighing all political, economic, and security dimensions, this idea can be seen as a vehicle with the potential to generate momentum around some of the more fundamental issues, thus creating incremental progress that improves the political landscape and helps reset the stage to negotiate a long-term peace.