The Long Revolution?

The closing sentence of Eliza Griswold’s “Talk of the Town” vignette in the May 16 edition of the New Yorker poignantly connects Abbottabad to the surge of protests sweeping North Africa and the Middle East: “I’m afraid of our economy,” an Abbottabad realtor insists, “not of Osama bin Laden.” This simple, yet powerful, statement transcends ideological warfare—be it against terrorism or for democracy—and reminds us that dire economic conditions are the most basic driving force behind the protests.

The closing sentence of Eliza Griswold’s “Talk of the Town” vignette in the May 16 edition of the New Yorker poignantly connects Abbottabad to the surge of protests sweeping North Africa and the Middle East: “I’m afraid of our economy,” an Abbottabad realtor insists, “not of Osama bin Laden.” This simple, yet powerful, statement transcends ideological warfare—be it against terrorism or for democracy—and reminds us that dire economic conditions are the most basic driving force behind the protests. Oddly enough, this realtor’s observation is in danger of losing its resonance in recent analysts’ attempts to explain just what exactly is happening in the region. With the common touchstones of authoritarianism, rabid Islam, and a passive population no longer credible, what has come to replace them?

One tactic has been to talk about “The Long Revolution,” which has been a headliner in the analysis of cultural and political change since the 1960s. This phrase represents the gradual acceptance and then popularization of a French school of historical thought (the Annalle) that focused attention on the longue durée and argued that change can only be assessed over extended periods of time—often necessitating the “century” as a unit of analysis. It was the title of Raymond William’s nearly 500 page reflection on how the evolution of new media played a key role in creating the modern world, as well as an attempt by leftist intellectuals to come to terms with the apparent lack of a world-wide revolutionary moment. What occurred instead, they argued, was a gradual—and total—transformation. But the specific political valence of this term was soon forgotten and it became a popular catchphrase for books on political revolutions in France, China, and Eastern Europe. The “Long Revolution” now serves as a title for subjects as diverse as the IT industry in India; the end of Apartheid in South Africa; the Easter Rebellion of 1916 in Ireland; and an exaugural address to Kingston University by Peter Scott on “The Long Revolution” in Higher Education.

In the past few weeks the phrase appeared in multiple attempts to address the uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa: Steve Coll’s New Yorker blog “Bahrain’s Long Revolution”; Vijay Prashad’s “The Long Arab Revolution”; and Paul Sedra’s “the Long Shadow of the 1952 Revolution” all follow a similar mantra, one that they shared with Chairman Mao. When asked to reflect on the relative success of the French Revolution, Mao reputedly answered, “It’s too soon to tell.” The significance of the term here is to give pause to media spokespersons who tend to use ahistorical explanations such as “an outpouring of humanity” or “a universal expression of a human need for freedom” and rely on generic labels such as the “Arab street” and an “Arab Spring.”

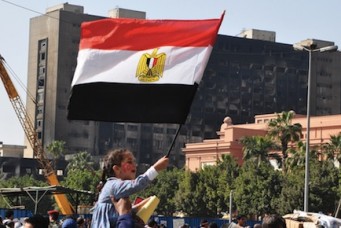

Such explanations and labels remove these movements from history and homogenize otherwise distinct regional experiences into one ethnic monolith. The “Long Revolution” is thus an attempt by scholars to counter shortsighted popular interpretations of recent events in the region. As Vijay Prashad argues, “For the Arab lands, these events of 2011 are not the inauguration of a new history, but the continuation of an unfinished struggle that is a hundred years old.” This “unfinished struggle” has roots in the nineteenth century, although Prashad’s analysis (like most current coverage of Egypt) addresses only the 1952-3 coup that led to Nasser’s wresting of power from a puppet monarchy. And yet, how “long” is long enough? Should we mention the so-called ‘Urabi revolt of 1881 (originally an effort by soldiers to contest an ethnic glass-ceiling imposed by British colonial officers) as the percipient struggle for this contemporary uprising? And how, once again, does this specific history then become part of a story for the “Arab lands” and an “Arab revolution”?

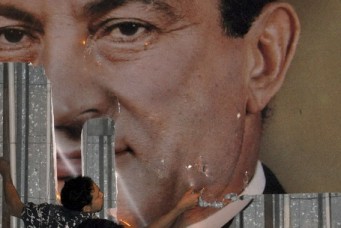

Further, this “long view” tends to portray a century of struggle as one, unending effort to achieve “democracy” in the region. This word has become so overburdened with meanings and so misused by all parties, that it seems more like a measuring rod for the IMF than a clear assessment of individuals’ economic, political and social well-being. Hillary Clinton in the early months of her tenure as Secretary of State called both Mubarak and Ben Ali “democratic” friends, and out of desperation Obama even conferred with Saudi Arabia on Egypt’s “democratic” transition.

But perhaps the gravest problem of this “long view” is the implication that not only you and I as readers, but also the very people participating in the protests do not fully comprehend the fact that they are part of a historical process. If the analyst’s best response is to throw history in people’s faces, are we not failing to give legitimacy to actions adopted in the present?

History matters, certainly. And certainly in our world of simultaneity and media over-drive a pause button is needed if a coherent picture of events is to be drawn. But this coherence shouldn’t remove agency from the people in the picture. A Tunisian street vendor’s woes and an Abbottabad realtor’s fears may be less about the centuries past, and more a call to a different future.