The 1973 October War and the Soviet Union

The Soviets tried to work out viable policies to deal with the fallout of the October War and Egypt’s pivot to the West

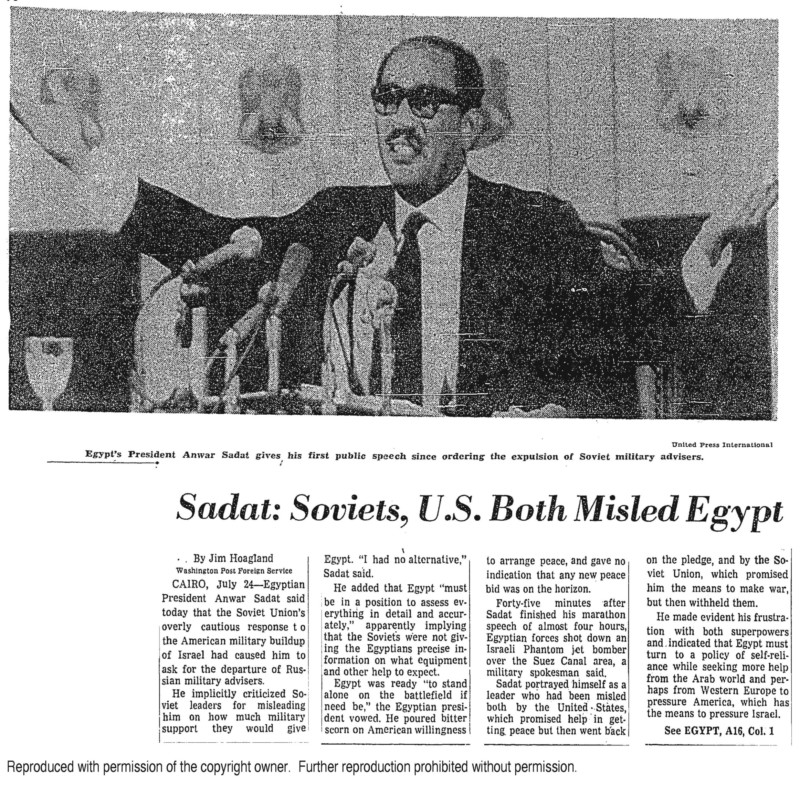

Sadat: Soviets, U.S. Both Misled Egypt: Sadat Scores Soviet ‘Caution,’ Says U.S. Works for Israel. By Jim Hoagland; Washington Post Foreign Service. The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C.

The fourth consecutive Arab-Israeli conflict in 1973, called the Day of Atonement War or the October War, shook the Middle East in the second half of the last century.

It was an exceedingly unusual war in many ways. First, the key role in the Arab coalition was played by Egypt. Second, unprecedented success was achieved by the Arabs—although temporarily and on a limited scale—which had a noticeable impact on the situation in the Middle East conflict zone. Third, Arab attacks against Israeli troops were mounted for the first time with no involvement of external actors. Lastly, the conflict came to a halt unexpectedly, leaving observers with the impression of a well-orchestrated performance.

This conflict was also discordant with the “zero-sum game” paradigm that had underlain all previous Arab-Israeli wars. This time, the conflict occurred against the backdrop of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s U-turn toward the United States shortly before the war and followed a decision made by Soviet leaders to withdraw their military specialists from Egypt. Another unusual aspect of this conflict was that Moscow formally learned about the war only after it began. Even more puzzling was that Moscow nevertheless continued to provide military assistance to the Egyptians.

Fifty years later, not all of the trials and tribulations inherent to the historic developments of that time are fully known or have been adequately interpreted. There remain many unanswered questions. As the authors of this essay, we decided to search for answers by focusing on memoirs and interviews of Russian diplomats, politicians, and journalists who were directly engaged in the events which unfolded. We place special emphasis on on an interview conducted by one of the essay authors Vitaly V. Naumkin with Ambassador Emeritus Andrey Glebovich Baklanov.

Vitaly was a student at Cairo University during the June 1967 War and worked as an interpreter for top Soviet delegations visiting Egypt and other Arab states. He later served in the Soviet Army for some time as a military interpreter and teacher at the Military Institute of Foreign Languages in Moscow. The two of us have remained friends for over half a century, which explains the very candid and heart-to-heart nature of these conversations.

Baklanov holds the rank of Ambassador Extraordinaire and Plenipotentiary and is one of the most prominent Russian diplomats. He has spent many years in Arab countries, including as head of the Russian diplomatic mission in Saudi Arabia. He is adviser to the Federation Council Deputy Chairman, candidate of Historical Sciences, and professor at the Faculty of World Economy and World Politics with the Higher School of Economics, a National Research University in Russia. He is an active participant in many international conferences and symposia; he and Naumkin are both associate fellows of the Geneva Center for Security Policy. Throughout 1969–1972, he worked as a staff member of the USSR Embassy in Egypt, initially as an interpreter and later as an attaché.

When first asked whether the Soviets expected that a new war would break out in the Middle East, Baklanov said that Moscow accurately predicted the timeframe within which the war could occur. Indeed, back in 1971, 1972, and the “decisive year” 1973, Sadat spoke about the inevitability of a new military confrontation between Egypt and Israel. Sadat’s comments were reminiscent of his late predecessor Gamal Abdel Nasser’s statements that if negotiations failed, then the territories Israel seized by force would have to be returned by force. This approach was most energetically promoted by Sadat after May 1971, when he arrested left-of-center elements in the country’s government and became the full-fledged president with all the powers that this post entailed.

Additionally, Sadat resolved to immortalize himself as the Arab leader who would return Sinai to Egypt after being lost by Nasser in 1967. Thus, Baklanov became witness to a tacit reputational competition between the late Nasser and the new president. Baklanov also pointed to operational data and intelligence sources which Moscow had access to through its long-established network of contacts, all of which were retained even after the withdrawal of Soviet military personnel from Egypt in July-August 1972.

Although there was an element of suspense around the definitive commencement of military action, it is most likely that Moscow, as well as Washington and a few other capitals, were well-informed of the date. Baklanov is quite sure that this war, quoting another Soviet Arabist, was a sort of “masrahiya” (performance), and that a number of privileged persons in the top political echelons of power in the United States, Egypt, and Israel were perfectly knowledgeable about it, as they had been evidently engaged in its preparation.

Why did Sadat Need a War?

Baklanov believed that in order to get peace talks started, Sadat needed to approach the Israelis from a much stronger position than the one held by the country after suffering a crushing defeat in the 1967 War. Sadat wanted to look everyone in the eyes, if not as a hero, then something very close to it. He urgently needed at least a limited or partial success, even at the risk of losing the favor of the USSR and certain Arab neighbors.

Meanwhile, Soviets had been losing influence. Their military departure from Egypt had not been ideal, even though commanding officers of the Soviet Armed Forces had insisted on the unavoidable reduction of their military presence well before 1972. However, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU CC) did not approve of this opinion, and, in April 1971, ruled that the Soviet Armed Forces should stay there for the time being, Baklanov explained.

“Basically, we were ready to leave. The war became an objective reality for us, but Moscow could not define a format for its interaction with the Egyptians until the very last moment. The ambiguity of our status lay in the fact that, formally, the Kremlin adhered to the policy of supporting Egypt as a state, but our relationship with Sadat had been growing more and more strained, especially since he had shoved out our military specialists before the war.”

It was clear that Sadat was steering a radical reversal of Egypt’s foreign policy strategies prior to the commencement of the war. He was preparing a document that would be subsequently referred to as the “October Paper.”

“Over that period of time, we had already formed a fairly adequate idea of the entire scenario that Sadat had in mind. We realized that it was a matter of drifting away from us and switching allegiance to the Americans. Most likely, with U.S. assistance after achieving limited military success, he would reach a compromise that would help to achieve his primary objective—to return, without any preconditions, all Egyptian territories seized by Israel in 1967.

Meanwhile, there was no mention whatsoever of the losses that would be sustained by other affected nations. We realized that this new line of policy meant an end to a lengthy period of a friendly, or almost friendly, relationship between the Soviet Union and Egypt, and Egypt’s transition to a different, probably pro-American orbit.”

The question was whether this transition to a pro-American orbit would be perceived as a hostile act in Moscow and to what extent the Kremlin was prepared to switch the Soviet-American relationship to a confrontational mode. We wanted to know whether the USSR had any illusions of sharing any common interests with the Americans at that time and whether it might be possible to reach an agreement with them.

The former ambassador clearly recalled that there was no such thing as general consensus among Soviet leaders or within the organizations that were entrusted with overseeing Egypt. On the one hand, many believed that—in the grand scheme of things, considering how the USSR had traditionally supported Egypt—the situation would settle one way or another. Perhaps the Egyptian line of policy would change, they conceded, but it would only involve a mere change in its foreign policy priorities. This belief was very strong.

On the other hand, there was a vision that the entire foreign policy mechanism had already been wound up for Egypt to accommodate unilateral collaboration with the United States and that this signaled the commencement of a completely new phase.

Egypt’s Pivot Begins

Baklanov spoke about his relations with someone he considered to be one of the most valuable assets: Egyptian Minister for Planning Ismail Sabri Abdallah.

“How did it happen that I, a young embassy attaché, had gained access to trust-based contacts with the Minister for Planning of a large state? In this respect, I should be thankful to Pogos Semenovich Akopov, the then Counsellor for Economic Relations and my immediate boss, who organized all these multi-layer contacts. Akopov wanted someone less visible than himself—the third person in the embassy hierarchy after the Ambassador and Minister-Counsellor—to maintain a communication channel with Minister Ismail Sabri, who was also the Director of the Egyptian Institute of National Planning. As a man of foresight, Akopov found Sabri—a former Egyptian Marxist, who treated the Soviet representatives in a truly remarkable way, both amicably and trustingly—to provide information to the Soviet mission.

Acting in advance, tentatively in November 1970, he acquainted me with the Egyptian more closely. Akopov arrived at the Institute of National Planning and said, ‘This is my attaché, my assistant, and also a postgraduate student of the Institute of International Affairs, he is writing a thesis on the Egyptian economy.’

Ismail Sabri handed me two huge volumes comprising 1,100 pages, which I read within two weeks. When I arrived to see him for the second time, I was citing those volumes, and he was astonished: ‘You are one of the very few people who have actually read these two volumes.’

This was the start of our trust-based relationship.”

Baklanov was able to gather significant insights from Abdallah about Egypt’s trajectory.

“He was saying that he and other key economic ministers had been instructed by President Sadat to draft a new concept that would rely on investment schemes from Arab oil-producing nations as well as Western states.

I asked a clarifying question: ‘Oil-producing nations in the first place?’

He replied: ‘Verbally, yes. This is a very shrewd concept, it seeks to distract attention, we want to get investment resources from everywhere and, certainly, these nations will be involved, but only together with Western states.’

As a matter of fact, the essence was reorientation toward the West. Abdallah de facto outlined the idea of a radical financial and economic reorganization of the country, targeting a totally different vector of development.

I reported this information to Akopov and the Ambassador, after which it was transmitted to Moscow. There was similar data confirming this conclusion apart from what I had reported. We tried to get Moscow to finally understand what was going on in Cairo. Information testifying to the same effect as that communicated by Ismail Sabri had been received along various lines—there were quite a lot of other sources that were known to me. That is why, overall, we tended to uphold the view that Egypt would most likely be moving away from the USSR systematically and transitioning to absolutely other rails.”

Reporting this information, which may run contrary to the ideals held in Moscow, was an act of courage, the former ambassador said. As is the case with all diplomats, relaying information that has a negative effect on the line of policy pursued by your state, or any data with a critical connotation for your superiors, is a sensitive, dangerous, and unpleasant task.

As an experienced ambassador to Egypt from 1970 to 1974, Vladimir Mikhailovich Vinogradov criticized the draft reports prepared by his subordinate embassy diplomats as lacking an extremely important element—something that would make the superiors “happy.”

Baklanov told us about a meeting that took place at the Soviet embassy in Cairo in April 1971, shortly before Sadat managed to solidify his position by lulling the vigilance of left-of-center political leaders in Egypt and contriving to neutralize them quite unexpectedly. At the meeting, the assignment to deliver a keynote report was given to the Counsellor for Political Affairs, Valery Yakovlevich Sukhin.

Baklanov remembers that Sukhin optimistically represented the first of two schools of thought about Egypt’s future foreign policy vis-à-vis the USSR, that Cairo was most likely going to abide by the earlier developed status quo of relations with Moscow. However, he pointed out that the new President Sadat appeared to be under pressure from forces hostile to the USSR, who were gathering momentum.

Only three of the diplomatic corps staff openly voiced their disagreement with the Counsellor. The first was Baklanov, who relied on certain data, reflecting the financial and economic performance of Egypt’s private sector playing a domineering role in its merger with the state-controlled sector, to arrive at the conclusion that Egypt was going to pursue a new direction. Key components of the new Egyptian model were liberalization and democratization. This new direction would not align with the Soviet model of socialist orientation.

Moreover, the change in direction was not because Sadat was forced to yield to the pressure exerted by some forces hostile to Moscow, but because he himself was the one who advocated for such a reversal of policy.

Baklanov’s point of view was articulated by two more diplomats, Georgy Ivanovich Martirosov and Robert Shakirovich Turdiev.

Turdiev made an interesting prediction:

“There is a Lebanese journal that has never been wrong. This journal wrote that in 1972 the new Egyptian President would completely break free from USSR custody in the military sector and would remove all Soviet military personnel.

We waited all through the year to check in on Robert’s words and much to our surprise, he proved to be right.”

Despite Egypt’s changed policy toward the Soviet Union, Baklanov said they were hopeful that things would turn out alright in the end.

“I was then summoned by Ambassador Vinogradov who told me ‘You were right. But, it is good for you to be smart, you are only responsible for your own area of work, and we are here to make sure that the scenario [Cairo’s pivot to Washington] you talked about does not materialize. So, my task and yours is to make things happen in such a way that your scenario turns out to be a flop and that the one mentioned by Sukhin prevails’.

I raised an objection: ‘Objectively, it will not work out the way Sukhin said.’ In any event, Vinogradov thought it appropriate to show that he had paid attention to the views articulated by us, young diplomats for the most part, at the meeting.

Incidentally, many of those who would later write that they knew everything beforehand, were keeping silent at the meeting in a cowardly fashion and did not utter a word in support of the “sadly negative” assessment. Perhaps they spoke later, but at this meeting, when an important final document was to be issued, they were reduced to silence. For this reason, the overall situation was complicated, there was a clash of opinions, but gradually, the view seeking to recognize the fact that Egypt had been drifting away from us, and moving in the direction toward the United States, began to gain ground.”

The Saudi Quotient

While the impressions of retired Soviet diplomats about their work at the embassy in Cairo half a century ago gives one insight about relations between the two countries, an overview of regional developments as well as Egypt-U.S. ties is critical to understanding the changes that gripped the Middle East in the 1970s.

“I haven’t altered my assessments about Cairo’s shift away from Moscow in the least, these were part of my thesis later, which I defended. But at that time, they seemed too bold to be broadly accepted. So, my thesis was labeled ‘For Official Use Only.’”

But on the question of contacts between Egypt and the United States, Baklanov was evasive, saying that he knew little at that time, only that very serious systematic talks were underway. Soviet diplomats were also unaware of the role Saudi Arabia played in bridging Egypt-U.S. ties. Baklanov says that he learned about the Kingdom’s role in earnest during a conversation with Defense Minister Prince Sultan Bin Abdul Aziz, with whom he was on good terms, many years later. He remembers asking the prince about the Saudi role.

“I am not only a diplomat; I am also a historian. I am puzzled by one question. Is it true that, within the period, when Sadat reversed Egypt’s policy orientation towards the United States, the chief of Saudi Arabia’s intelligence agency was actively engaged in this reorientation effort when he came to Cairo and to the United States to conduct negotiations? Did you truly play a key role? I remember your visit, you also spoke in favor of halting the Soviet military presence, etc.”

Baklanov recalled Prince Sultan saying:

“Such were the times. I wouldn’t like to speculate on the details, perhaps we could discuss it in greater detail one day. Yes, we did contribute to a radical reversal of Egypt’s policy aimed at forging friendship with the United States because we were on friendly terms with them ourselves. There were different circumstances then.”

In other words, the Saudis admitted to having assisted in that process, but did it mean that they offered material support to Egypt for such a reorientation effort?

Baklanov believed that they were “just beginning” to do so in the buildup to the war. The investment law mentioned by Ismail Sabri Abdallah in a conversation with Baklanov had already been drafted in 1971. At the time, conversations with the Saudis were well underway and they promised that if Cairo adopted a more reasonable policy—rejecting its socialist experiments, which had stirred up commotion among the Arab people, including on the Arabian Peninsula—they would support Egypt. In 1971, the first social bank An-Nasr (Victory) was set up, based almost entirely on Saudi capital. Yes, monetary injections had already been made.

Another question arises then about how accurate were Soviet in their evaluations of the interests and ambitions of the region’s key players, chiefly Egypt, Israel, Syria, and Jordan?

Baklanov emphasized that the Egypt file was given particular attention within Soviet diplomatic circles as an inalienable part of Soviet foreign policy.

“We had no contact whatsoever with the Saudis and we were not engaged in monitoring their situation. Neither did we have any close relationships with the Jordanians. Later, after the 1970 events, [known as Black September] we tried to grasp what was going on there in connection with our relationships with the Palestinians.

As for Syria, we proceeded from the premise that Damascus was the organizer of the ‘rejectionist bloc.’ Broadly speaking, we were prepared to face a split within the Arab world, a situation where Egypt, while drifting away from collaboration with us, would be transitioning to confrontation with countries that might form an alternative center of power in the Arab world, led by Syria.

Israel, meanwhile, was the focus of our attention. We had a staff member at our Cairo embassy, Komissarov, who had earlier worked in Tel-Aviv, so he continued to monitor developments in Israel. There was a common perception, and I adhered to it, that we needed to restore our relationships with Israel at an accelerated pace. However, Moscow was not supportive of that idea, and neither was Akopov.

We, the younger diplomats, certainly speculated about it. We didn’t proceed from the assumption that it was appropriate to forge relationships with Israel on a positive note, but because we found ourselves in a pretty silly situation. We had ruptured contacts with Israel to please the Arabs. However, in 1970, Sadat expressly stated: ‘Dear Soviet comrades, unfortunately, it so happened that your mediation effort was not enough.’

So, Sadat made his message clear: ‘The key to resolving the problem lies in the hands of the Americans,’ as they had been in contact with both sides. We felt like idiots; it turned out that we had severed our relationships with Israel for the Arabs to benefit, and now they were accusing us, as mediators, of being inadequate.”

Baklanov said he advocated openly for the necessity to resume ties with Israel, but he did not insist on it, “as it was not his field of competence.” While allegiances were shifting in the Middle East, the Kremlin appeared to be holding steadfast that its policies and interests in the region regarding the Arab-Israeli conflict would remain the same.

“Moscow distinctively formulated its goals in the Arab-Israeli conflict in early 1971 and these goals remained almost the same until after the 1973 War. However, that approach turned out to be a noticeable failure. Effectively, another concept came into action. Thus, the incomplete process of revising our concepts about the Middle East had been in evidence for a long time.”

As the Soviets were trying to adjust to the new realities and identify the track that post-1973 developments would take, their biggest challenge was how to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict Moscow had to decide whether to recommit to the peace process on a fresh basis, with no linkage to UN Resolutions 242 and 338, or to stay within the confines of something that sounded very good in the Kremlin, but failed to work properly.

Baklanov said that there was a lack of clear-cut vision and a noticeable inadequacy in how the Soviets pursued their goals in the Middle East. Ultimately, and until new concepts on Middle East policy could be clearly stated, substantiated, and widely supported, the Soviets would adhere to their status quo policies in the region.

This left open the question of how integrated the discussions on the Middle East had been among the various departments of senior government in the Kremlin. There were miscalculations on the Soviet side, which makes it all the more important to highlight the difference in perceptions then and now when considering how that pivotal conflict influenced the regional balance of forces.

Baklanov noted that retrospective evaluations today are dramatically different from the official assessments of the early 1970s.

“I don’t mean the assessments made by experts, which were also very different. You can come to the Russian libraries and look through the book titles, which speak for themselves – the Camp David Collapse, the Camp David Conspiracy, etc. The war had already paved the way for the Camp David process, but Moscow was inclined to perceive it, along the official line, in an exclusively negative light, that it was allegedly founded on an anti-Soviet platform. However, afterwards, a peace process arose out of it. And, at that time, some striking ambiguity was in evidence: on the one hand, a peace process was looming ahead, and on the other, we condemned the phenomena that formed its basis. That was exactly the way as matters stood then. Politics was not really streamlined for a long time to come.”

Baklanov conceded that after the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference co-sponsored by the United States and Soviet Union, previous negative assessments were revised post factum.

For example, the peace treaty with Israel that had been signed by Sadat—for which he had been branded as a traitor—now appeared to be quite acceptable.

Furthermore, the draft Palestinian resolution was much more acceptable in the Camp David agreements than any other toward resolving the Arab-Israeli conflict. “If we had agreed to that plan earlier, although it would not have led to the formation of a state, and a degree of self-management,” Baklanov said. “It would have been the most feasible, even more than in the best document related to this issue, which was the plan proposed by U.S. President Bill Clinton in 1998.”

Relations with Egypt

While the war in 1973 did not change the Soviet approach to Sadat-ruled Egypt at first, over time, and in the wake of the Camp David Accords, Moscow did harden its position.

“Only in the wake of the Camp David Accords did we start to criticize them most severely. After the 1973 War, there was an attempt at launching Arab-Israeli negotiations [the 1974 Geneva process], in which one of the participants was V.M. Vinogradov. Aside from this, even during the war, there was a very odd situation in place. The war was waged without us. Sadat informed us about it for the first time only when Egyptian forces were already crossing to the other bank of the Suez Canal. Sadat called Vinogradov, but instead reached his secretary Vafu Guluzade (The then Second Secretary of the USSR Embassy), talked to him and said enthusiastically that the Egyptian Army had already reached the East bank. That is to say, Sadat did not think it necessary to give an official notice of it beforehand.

Nevertheless, during the war, we provided a lot of assistance to the Egyptians, there was a corridor designated for the deployment of our military equipment, and we also got something, as far as I know, in return, in an amicable way, for example, specimens of Western weapons. We started with a very old British Centurion tank, that was made available to us very easily, and then we received a more modern U.S. M48 tank. From that time on, our Egyptian counterparts began to pass over electronic devices, various improvements under the bonnet etc., less enthusiastically.

Yet, notwithstanding, during the war, we had a channel allowing us to study the specimens of weapons and technology, including combat drones. For instance, one of the first combat drones of Western [American] manufacture at our disposal for the purpose of studying was delivered to us precisely during the 1973 War. They were very interesting, and in any event, according to our evaluation, they were pretty good at furnishing reconnaissance data.”

While historians today might debate whether Moscow should have withheld its military support for Egypt after 1972 and at the height of the October War, Baklanov believed it was a fait accomplis for the Soviets. In terms of the geopolitical realities and in accordance with the integration patterns at the time, he believes Moscow’s assistance was inevitable.

“We supplied a lot of weapons to the Egyptians across that bridge. Suddenly, over a few days, our military support was resumed, given the events that took place. For us, it seemed somewhat odd, as we had already broken up with them. This ability of ours to forget everything suddenly and to embrace each other again, quite unexpectedly for all, is a purely Russian trait, and we could not get rid of it for decades. In that episode, it was there for all to see. We couldn’t have behaved otherwise.”

Baklanov recalled a conversation with the military attaché at the Cairo embassy at the time of the war.

“Half a loaf is better than no bread. They had been already slipping away from our control, but still I, as a military attaché, was obliged to get something to hold in my hands,” he told Baklanov. “And I did it. I sent to Moscow a whole range of very interesting pieces of weapons. For this reason, I feel gratified with the outcome of the 1973 War,” the military attaché added.

The Sadat Conspiracy Theories

There have been numerous theories in circulation since the end of the 1973 October War claiming that Sadat had an agreement with the Americans that he would halt military action when he reached a certain point in the Sinai Peninsula and that the Syrians were trying to prevent this from happening.

It was exactly that way, Baklanov revealed.

“I have such a suspicion, because when Vinogradov asked Sadat: “Why did you stop?”

Sadat could not answer him. I also asked Vinogradov about it, and he said that Sadat’s answer was: “Am I supposed to run together with my troops?”

A very strange answer. Yes, they stopped and decided it was enough. Basically, they amassed a minimum of psychological effect for positive energy.”

The Syrians expected that there would be a general offensive launched from both battlefronts.

The ex-ambassador replied that it was hard for him to say anything about the Syrians. As a matter of fact, Baklanov said, the Syrians had a very good intelligence service and they knew exactly what was going on in all countries, including Israel and Egypt. However, and despite having this intelligence, the way they reacted publicly was different. Ultimately, the Syrians had to abide by their own plans coordinated with the top command, at the top of which was the late Hafez Al-Assad.

“I believe,” concluded Baklanov, “that the 1973 War remains a breakthrough moment in Middle East history which requires continued study as we gain more data, we will gradually approach the stage when we comprehend the essence of all the events occurring at that time,” he said.