Scrolling Social Media Sentiments on the Gaza War

Despite efforts of platforms like Meta to curb political content generally, frustration and sympathy for both sides of Israel’s War on Gaza continues to run deep among users

14-year-old Ahmad Salaymeh, a Palestinian teenager who was released on November 28 as part of a hostages-prisoners swap deal between Hamas and Israel, and his father Nawaf Salaymeh talk through social media after Ahmad was prevented from returning to school, in Jerusalem, December 7, 2023. REUTERS/Ammar Awad.

It is virtually impossible to not come across the images of bodies of dismembered children and limbs sticking out from beneath the rubble of destroyed infrastructure in Gaza as the post-October 7 conflict shows no signs of ending.

Social media users scroll past such images juxtaposed with their friends’ birthdays and weekend getaways. Even though the world goes about business as usual, they have found themselves inadvertently engaged in Israel’s war on Gaza, making social media platforms the commonplace like a public square of the global village.

The escorted or denied access of foreign journalists to Gaza also nudges people toward social media for real time updates and firsthand accounts of Palestinians. Often in conflict zones, such as Syria, Sudan and Ukraine, citizens journalists or content creators are ensnared to become war reporters.

As content creators take up such roles, their followers or social media users have also become active bystanders of the war bound to see, think, like, repost, internalize, respond and comment on social media about the unprecedented violence since October 7.

The exchange of sentiments in social media platforms, particularly Instagram in the context of this text—and their user-facing architectures that enable social interaction and content sharing online, such as the like button, comment section, repost feature and so on— represents the collective consciousness of the world where users are confronted with the visceral accounts of Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank.

Left to their own devices, Palestinians are documenting life and creating a public repository of their lived realities through their Instagram profiles where the world watches them eating a moldy citrus for breakfast, offering Friday prayers next to what was once a residential building and children hosting a press conference pleading to the world to end bombardment of their homes.

Instagram followers can go as far as empathizing, imagining, dreading in disbelief and in instances expressing contempt for the suffering of Gazans. One way people have exhibited solidarity or outrage, has been by identifying internet figures and engaging with them through the architectures of their Instagram profiles (such as the like, comments, comment reply, follow, unfollow etc) or beyond, in spaces outside of the creator profile (eg: your instagram story, someone else’s comment section etc).

For instance, one such face is that of photojournalist Motaz Azaiza who has over 18.3 million followers and over 2,300 posts on his Instagram profile. However, the hashtag with his name #motazazaiza has over 14,500 posts on Instagram. Although all of the posts under the hashtag are not directly linked to the war, they are an indication of the buzz his name has created on Instagram. This is an example of how users have taken a face/persona they recognize beyond the realms of the creator’s profile to other spaces within the platform. The hashtag can be taken as a vague representation of the collective amount of times Motaz Azaiza has been referenced across the echo chambers of the platform.

Personal and Political

Instagram spaces have been transformed into a mosaic of personal and political forums by users who develop a parasocial relationship with content-creators-cum-war-correspondents, as they witness the conflict in much the same fashion as they watch their favorite influencer document ‘a day in the life’.

The creators are known by their first names, and spoken of as common friends. Their stories are embedded in people’s feeds alongside the normalcy of others they follow during their work break, when they scroll on Instagram, or randomly at any other time of the day. Unlike a TV or a radio, users are not able to turn off their Instagram feeds and go to bed. Instead, they bear witness to real time news from the war-torn enclave and express concerns for the safety and well being of the personas they have developed attachments for.

The interactions of people with profiles through following, commenting, liking, liking other’s comments or replying to comments, are exhibited within the architectures of the profile. When people go beyond the profile—when they mention the person, their name, or anecdotes coming from the profile—they are identifying a narrative conduit for their own social media or instagram spaces, furthering their presence beyond the architectures of his/her profile. Perhaps, in the context of the war in Gaza, citizen journalism seeps into the lives of people surfing through the horrors of war on Instagram and manifests within the same spaces where individuals engage in journalistic practices to disseminate narratives or information coming from profiles and figures they perceive as credible. They do so by echoing the voices coming from the side they support, and embellishing their engagement with the relevant hashtag, depending on the message being shared.

When people ascribe to narratives and speak about issues offline in the physical world, it is impossible to always document their interactions. However, as we like, comment, share, and respond to issues online, these can be mostly documented in hashtags, counts of likes, comment replies, etc. These interactions make it relatively easier to measure public engagement.

For instance, hashtags loaded with political implication, such as #freepalestine, have over 9,442,504 posts while #freepalestinefromhamas has over 41,424 posts. Similarly, #freeisrael has over 33,031 posts, #fromtherivertothesea over 134,452 posts, #israel with 20,837,901, and #palestine with 11,358,954 posts. The volume of content representative of the above key words depicts the presence of participation of people and contestation of narratives surrounding the conflict. On Instagram, something as simple as liking a post with a specific hashtag enables people to ascribe to a narrative and possibly amplify it.*

The Metaverse of Censorship

Meta has several platform mechanisms to regulate posts before the audience can view and process them. For graphic content, for example, they blur the imagery, provide a disclosure on the screen and let audiences ‘’see why’’, and allow them to decide whether they want to ‘’see photo’’ or ‘‘see video’’.

These mechanisms have been used extensively in posts on the war in recent months.

The ubiquity of the content from Gaza on Instagram can be attributed to the sheer volume of posts dedicated to the war on the platform; hashtags like #gaza hosted 6,194,387 posts as of the first week of April 2024.

Creators posting about Palestine have reported to being shadowbanned, flagged for violating community guidelines, or their accounts permanently suspended. Human Rights Watch in November 2023, identified six key patterns of systemic censorship of Palestinian content by Meta namely, removal of posts, stories, and comments; suspension or permanent disabling of accounts; restrictions on the ability to engage with content; restrictions on the ability to follow or tag other accounts; restrictions on the use of certain features; and shadow banning.

Similarly, digital rights group Access Now, has flagged other ways which reveal Meta’s ‘‘systematic censorship, algorithmic bias, and discriminatory content moderation’’. They say that Meta employed flawed and discriminatory content moderation policies, inconsistent and discriminatory rule enforcement and arbitrary and erroneous rule enforcement while ‘’cherry picking human rights’’. HRW also stated in its report that the margin of error in such content moderation policies is likely to increase, failing to comply with the Human rights standards maintained by the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Meta, like any other business is expected to comply with the United Nations General Assembly’s founding principle wherein ‘‘Business enterprises should respect human rights. This means that they should avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved.’’

After October 7, Meta published a blog post about its efforts in the ongoing war (last updated on December 7, 2023). In their first post on October 13, they said: “We apply these policies equally around the world and there is no truth to the suggestion that we are deliberately suppressing voice.” Highlighting their efforts in regulating social media posts about the ongoing war, they mentioned that the Meta’s Oversight Board has taken ‘‘two cases from user appeals related to the Israel-Hamas War for expedited review”, a process by which the board issues “accelerated content decisions within 30 days in exceptional circumstances’’.

Recently, Meta also rolled out an update on February 9 for Instagram and Threads, stating that they will not “proactively recommend political content from content you don’t follow … but people will have control to see them if they want to”. How that is going to play out in Gen-Z coded internet lingo versus Meta’s automated content ranking systems is a story for later. Similarly, professional accounts can also check their Account Status to know their ‘eligibility for recommendation based on whether they recently posted political content”.

In another post about their approach to political content in their Transparency Center, Meta cited that “people have told us they want to see less political content”, that they are now “using AI systems to determine what is worthy of people’s time” and have “shifted away from ranking political feed on Facebook on the basis of how likely people are going to engage with the post”. The Internet Watch Foundation has called this move an attempt to throttle politics.

Measuring Public Opinion on Instagram

Sentiment analysis is a process of gathering and analyzing people’s perceptions of opinions via identification and extraction of subjective information through text. A comprehensive sentiment analysis of the Instagram comment section of journalists reporting directly from Gaza at some point in the war paints a picture of what people are expressing and what type of response they are enticing.

This includes a systemic analysis of sentiments exhibited by the viewers toward the journalists and the war at large. The sentiment analysis includes the first twenty comments (as they appeared during the time of writing) in eight videos, picked at random, of four prominent journalists. The analysis features prominent Palestinian figures on Instagram, Plestia Alaqad, Motaz Azaiza, Bisan Owda, and Hind Khoudary. It scores each comment based on the number of likes and the number of comments it gained in response. The scores however, are not equivalent. The number of likes in a comment is deemed as an affirmative response towards the expressed sentiment. For instance, if someone likes a comment that praises the creator, it is considered that the person liking it agrees with the praise given i.e. if there are 31 likes in a comment praising someone, it means 31 people agree with this praise given.

Meanwhile, if there are 42 comments responding in the same comment, it does not necessarily mean that all of them are in agreement with the praise. In many cases, comment replies might be in disagreement with the sentiment expressed. However, the number of comment responses being high translates into what sentiments people contest the most or support the most.

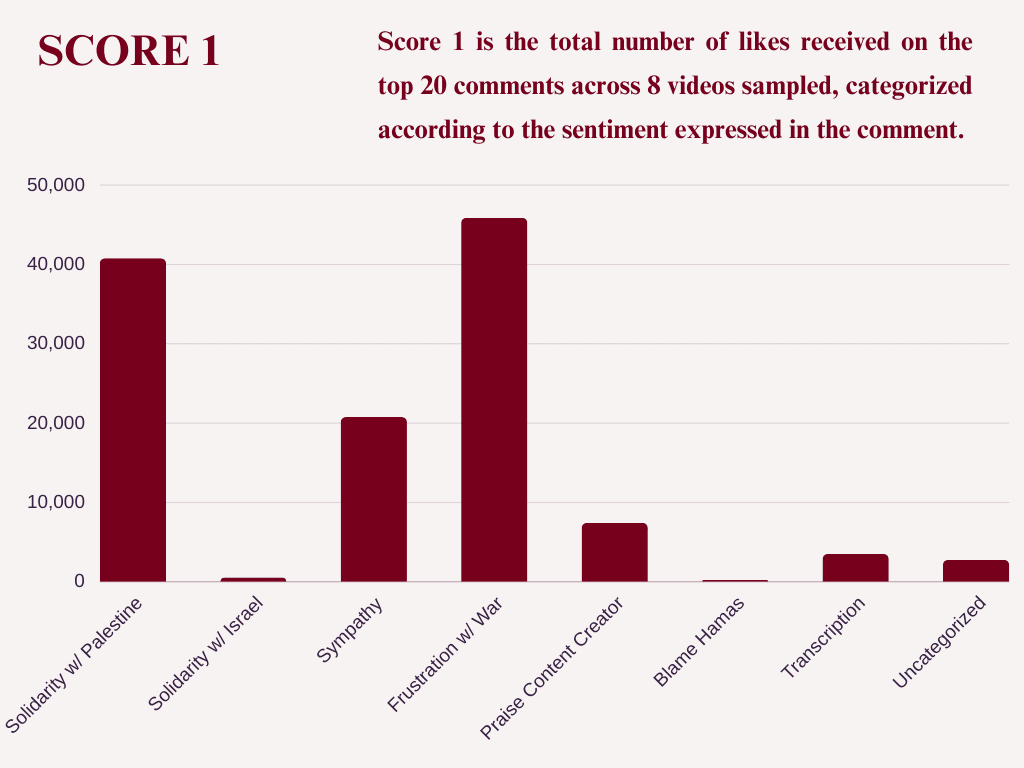

The number of likes amassed by each comment will be represented by Score 1. The number of comment responses is represented by Score 2. Whether these responses are affirmative or contrary to the sentiment expressed in the comment is not explored in this study.

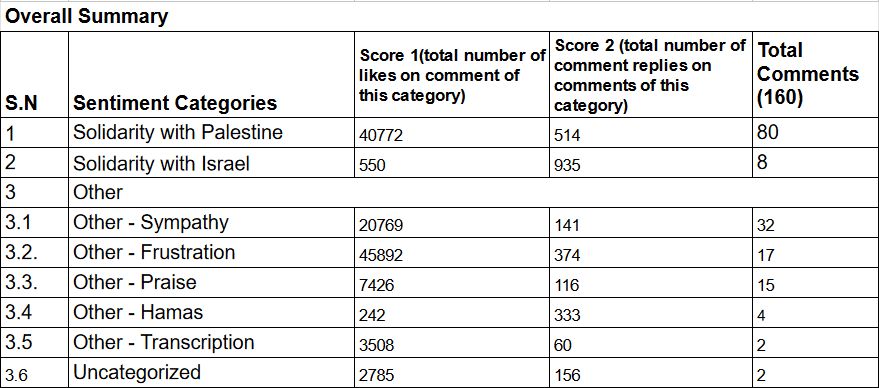

A total of 160 comments was retrieved from the profiles of the four journalists, and categorized into three broad themes:

- Solidarity for Palestine;

- Solidarity for Israel; and

- Other.

Comments that did not explicitly meet the first two categories are sub-grouped into five ‘Other’ categories: Sympathy; Praise for the creator; Frustration about the war; blame on Hamas for the war; and Transcription of the videos.

Two comments are Uncategorized as they are not similar enough to be placed within a category of their own and do not fit into Other, or the first two categories.

Of the 160 comments, the highest numbers fall under the sentiment of Solidarity with Palestine (80); with Sympathy (32), Frustration (17) as second and third most commented sentiments, respectively.

The fourth most recurring sentiment was Praise (15) for the content creators followed by Solidarity with Israel (8), Blaming Hamas (4) and finally Transcriptions (2).

Figure 1: Table 1 – Overall Summary

The two comments were Uncategorized because one of them suggested that Palestinians move to other Arab countries and the second one said the word ‘English’ in Arabic. The second comment was made by Motaz Azaiza on Hind Khoudary’s post so it has amassed quite a few likes and comment responses.

In terms of Score 1, Frustration was the most resonated sentiment with 45,892 likes for 17 out of 160 comments, followed by Solidarity for Palestine with 40,772 likes in 80 comments. Similarly, Sympathy is the third largest category of sentiment expressed through 20,769 likes in 32 comments.

Score 1 in this context is the total score of likes received across the profiles, in all 8 videos.

Next is Praise for the creator with 7,426 likes in 15 comments and Transcription of the video with 3,508 likes on two comments. There were also two Uncategorized comments with 2,785 likes on them while eight comments expressing Solidarity with Israel amassed 550 likes and finally three comments Blaming Hamas for the war accumulated 242 likes.

On the other hand, measurement of Score 2 gives us a different insight. The comments encapsulating sentiments expressing Solidarity with Israel gained the most comment replies of 935, followed by comments in Solidarity with Palestine with 514 responses, and Frustration with 374 responses in third place.

Blame on Hamas is the fourth most popular comment, accumulating 333 replies; Uncategorized is the fifth with 156 replies. Sentiments expressing Sympathy received 141 comment responses followed by 116 comments with Praise for the creator and 60 for Transcription.

Looking at the numbers, the public sentiment does not necessarily oscillate between Solidarity with Palestine or Solidarity with Israel only—the public is frustrated and sympathetic toward the people suffering in the ongoing war who they also praise for sharing their lives online. The numbers indicate that people are most likely to engage with comments that express solidarity with one or the other side of the war.

There are interesting discrepancies which emerge upon analysis. For example, the volume of the number of comments expressed in Solidarity with Palestine is eighty but the volume for expression of Solidarity with Israel is eight, the first being ten times larger in number.

However, the second is much larger in terms of textual expression from users: Solidarity with Israel amassed 935 comment responses while Solidarity with Palestine amassed 514.

The discrepancy between the likes and comment scores indicates that the public seem to be engaged in the war through their fingertips even though emotions run deeper.

Analysis of the data also indicates that Sympathy and Frustration are the most expressed emotions as these categories score high in both number of likes and comment responses.

Perhaps, witnessing the war on social media also made it easy for people to engage in a distant reality that has sprawled across their feeds, merging with the simultaneous normalcy of some outfit of the day or get ready with me Instagram posts.

How the war unfolds in upcoming days, how it manifests in our most used social media platforms, and how these platforms will respond to it will most likely continue shaping the public response as well.

Data used can be found on this sheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1sChlU6EFYM6bU9_T1U2gnOND1F83f_UpKlIE-uIj6TA/edit?usp=sharing

*The figures for the number of posts under each hashtags were collected on April 13, 2024. The figures are not representative of posts only after October 7, but all posts made under the hashtags.

Ayusha Chalise is an Erasmus Mundus Scholar pursuing a joint MSc in Digital Communication Leadership and an MSc in International Development from the University of Salzburg and Wageningen University and Research. She comes from Nepal, where she worked as a TV journalist across Nepali national television for a little over 4 years. She also worked two years at the International Foundation for Electoral Systems Nepal as a Social Media Consultant to run voter education campaigns in the elections of 2022. Ayusha also worked as a freelance journalist for online publications. She graduated from the Asian College of Journalism in India with a PostGrad Diploma in New Media Journalism and from Kathmandu University with a Bachelor in Community Development. Currently, she is doing her MSc. thesis research on the online political discourse of Nepal over Facebook.

Read More