Climate Change, Conflict, and Gender Inequality in the MENA Region

Climate change—in the absence of legal and social protections—works as a threat multiplier that perpetuates gender inequalities and worsens socio-economic injustices in the MENA region

The Middle East and North Africa is one of the world’s most gender unequal regions; it will take an estimated 140 years for MENA countries to establish parity between men and women. The existing gender gap has had serious ramifications for women, limiting their access to the labor market and economic empowerment. These women are not only hindered by challenging economic conditions and political instability, but also by restrictive gender norms.

In addition to rampant gender disparities, the MENA region is also identified as a climate change hot spot; it is home to 13 of the world’s 20 most water-stressed countries. It is expected that about 90 million of the region’s inhabitants will be at risk of water stress by 2025. Additionally, the region is warming faster than the global average. Researchers predict that summer temperatures will rise by 4°C by the end of the century. The combination of heat and drought is set to accelerate desertification, which is extremely concerning for a region whose terrain is already over 82 percent desert. Existing social problems, like gender inequality, exacerbate these growing environmental hazards. Understanding how climate change intersects with gender in the realm of agriculture, migration, and conflict is key to designing effective and lasting policies that support women’s safety and empowerment.

Land Workers, Not Landowners

It is estimated that of the approximately 1.3 billion people living in poverty in the region, roughly 70 percent are women. Women are also the primary users of natural resources because of the gendered productive and reproductive responsibilities which are dependent on these resources. Women in developing countries are responsible for growing vegetables, rearing livestock, food storage and transport from the villages, food processing and production, and fetching water and fuel wood for households. Yet women are always underrepresented in natural resource decision-making and are often denied land ownership.

Agricultural production, for example, depends largely on rural women, with women representing over 50 percent of the agricultural workforce in the region; women make up 45 percent of this workforce in Egypt and over 60 percent in Jordan, Libya, and Syria. Despite the prevalence of women in agriculture, discriminatory laws and social norms impede women’s access to necessary resources, such as land, water, and credit.

A report from the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas indicates that women own less than 5 percent of the agricultural land in the MENA region. Women’s land rights are restricted not only by a lack of implementation of existing laws but also by prevailing patriarchal gender norms that often discriminate against women, resulting in obstacles for women to acquire and retain land. Although Sharia-based inheritance laws do not prevent women from owning land in the MENA region, there are a number of factors that curtail women’s ability to exercise control over land.

These include the complexity of land registration systems, lack of access to information and knowledge about land laws and national land policies, and customary laws that in some cases force widowed or divorced women to cede their share of family land to their brothers in exchange for economic support.

In the light of the aforementioned issues, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN indicates that out of eight world regions, the MENA region has the lowest rates of female agricultural land owners. In Jordan, for instance, women’s land rights are secured through comprehensive legal frameworks but women still own only 17 percent of land, while men own 48 percent. Similarly, while Sudan’s national land laws do not discriminate based on gender, women are still more likely to be landless. Even when women own land, male-biased inheritance practices and regressive social norms obstruct women from land management and impede their access to the necessary credit, capital, and technology. For example, male members of the household may coerce women into relinquishing their rights, ejecting them from their land in case of the death of a husband, and excluding them from decisions about the sale, lease, or management of their land.

The impacts of these legal and cultural restrictions are exacerbated by climate change, which poses a growing threat to the natural resources required for agricultural production. For instance, due to traditional gender norms, women are often employed on farms as casual workers, giving them very little social security in the event of a climate crisis. Thus, they are often the first to be laid off in times of disasters like droughts and crop failures. When these climate disasters take place, women farmers (who are often heads of households or the primary breadwinners) are likely to lose their livelihoods.

Climate hazards can also worsen pre-existing gender divides and emphasize social vulnerabilities. For example, it is estimated that 50 percent of Syrian refugee women working in Lebanon are employed in agriculture because it is one of the few sectors open to refugees. Many of these women are also the heads of their households. However, many have lost their jobs in recent years due to significant crop failures (triggered by heat waves) that dried up many of Lebanon’s rivers and springs. These women, who are refugees with limited job opportunities and employed only in a casual capacity, have no way to mitigate these economic losses or obtain more stable work. In the MENA region, mobility at times of climate disasters is not gender neutral. Climate-induced women migrants are faced with multidimensional vulnerability and insecurity throughout the migration process and even after they settle in their new host communities.

Vulnerability in Migration

As the climate crisis intensifies, more people have been driven to leave their homes, displaced either within their countries or across borders. It is estimated that 223,000 internal displacements occurred as the result of severe droughts, flash floods, storms, or other climate catastrophes throughout 2021. In the face of climate shocks, men are more mobile; they are more likely to migrate to urban centers in search of alternative employment opportunities. Conversely, patriarchal structures and gendered social obligations limit the mobility of women, both inside and outside the household, particularly at times of climate shocks. A report issued by the UN Women Regional Office for Arab States shows that women in the MENA region carry the biggest share of care work, performing 4.7 times more unpaid care work than men—the highest female–to–male ratio anywhere in the world. This means that women are often left behind to handle the family care responsibilities. Furthermore, with a higher level of illiteracy among women in rural communities, they have more difficulties than men in understanding early warning messages. Women’s mobility is also restricted by the fear of sexual and gender-based violence outside the home.

For example, in Syria, the record drought from 2006 to 2010 drove dispossessed farmers—most of them men—from the country’s breadbasket to urban peripheries, leaving the women behind. This forced women to become heads of household, taking on the men’s farming work in addition to their regular (unpaid) household responsibilities. This made them susceptible to various forms of exploitation and violence.

Climate-induced migrants of all genders face complex and significant risks during the moving process. However, women migrants in particular are faced with multidimensional vulnerabilities and insecurity throughout the migration process. These vulnerabilities continue even after they settle in their new host communities. For instance, female migrants may be separated from their families and subjected to exploitation and human rights violations. These include a heightened threat of arbitrary detention, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking. Female refugees are particularly susceptible to trafficking when they are moving through unsafe migratory routes without concrete protection measures (women account for 71 percent of human trafficking victims).

Sexual violence against women migrating via the Mediterranean routes, particularly through illegal channels, is endemic. A recent study showed that Syrian refugee women who lacked the funds to pay smugglers and border guards were particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse and exploitation. This has been seen in refugee camps in both the MENA region and Europe.

In addition to a greater likelihood of being subjected to human rights violations, women are 14 times more likely to die than men; this is due to the difficulties women face in accessing adequate health care, food, water, and sanitation.For example, it was found that women migrants suffer from inadequate health services due to poor health literacy (particularly across sexual and reproductive topics), challenges in navigating complex healthcare systems of the host countries, and fear of prosecution especially among undocumented migrants.

Even after reaching their destinations, women refugees are more likely to experience intersectional forms of discrimination. This discrimination is based on a compounded set of factors, including place of origin, religion, race, and socioeconomic status. These factors can restrict women’s access to employment, housing, education, and health services and make them vulnerable to social exclusion.

Traveling between countries is particularly difficult due to a lack of consistent legal protection for refugees across borders. The Geneva Convention, which handles international regulations, outlines protections for those who are persecuted for their political orientation, race, nationality, religion, or because they belong to a specific social group. The Geneva Convention does not provide protection for people who are displaced because of existential climate risks. However, there are a number of other policy frameworks that address the intersection of climate-induced migration and gender, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Platform for Disaster and Displacement, Global Compact on Refugees, Kampala Convention, and Sendai Framework on Disaster Risk Reduction.

These international instruments offer important visibility to climate refugees and to the extensive risks associated with climate change, particularly gender-based violence. However, they are not legally binding; states are not required to provide legal protection for climate-induced migrants, whether within or between borders. Furthermore, there is no regional agreement that addresses cross-border migration in the context of climate change. Instead, most countries prefer to develop individual legal frameworks that mainly address internal, rather than cross-border, displacement. Only two countries have enacted relevant policies to protect internally displaced people, Iraq in 2008 and Yemen in 2013.

Climate change worsens the severity of conflicts particularly for women. In the MENA region, the deteriorating securitarian conditions, coupled with the dire climate hazards, are exacerbating the challenges of water scarcity, food insecurity, and forced displacement.

A Warming and War-torn Region

Climate change, in combination with poor governance and structural inequalities, can worsen the severity of existing conflicts and increase the likelihood of future ones. In 2020, six fragile and conflict-affected countries in the MENA region were hit with severe climate hazards. Droughts, floods, and other climate disasters exacerbate the depletion of natural resources; this scarcity is often found at the center of regional conflicts.

For example, conflicts among agro-pastoralist communities often erupt over inadequate pasture space and water points; it is estimated that the number of such conflicts is likely to increase by 54 percent with every one degree increase in temperature. This is particularly relevant in the MENA region, where agriculture, fisheries, and livestock account for about 15 percent of the total population’s livelihood; additionally, 70 percent of the region’s crops are rain fed, which is more susceptible to weather changes than other forms of irrigation. Therefore, changes in precipitation and extreme weather events present a major threat to food security and economic stability, escalating the risk of violent conflicts.

This trend is evident in Syria where multiple studies emphasize the importance of the 2007 and 2008 multi-year drought, which caused widespread crop failure, worsening conditions for the rural population, and increased migration from drought-affected regions. The issues of water scarcity, food insecurity, and economic distress, combined with pre-existing soci-economic inequalities and political discontent, intertwined to play an important role in the eruption of Syria’s violent insurrection in spring 2011.

Syria’s prolonged crisis has had a profound impact on its population, with 6.8 million refugees displaced internally and more than 5 million displaced to neighboring countries; roughly half of these refugees are women. These women were extremely susceptible to sexual and gender-based violence; girls were obligated to drop out of school and the majority of displaced women were (and continue to be) deprived of their most basic needs, like food and healthcare.

Similarly, in Yemen, climate change plays an important role in the protracted armed conflict ongoing since 2015. Water scarcity has historically been a pressing issue in Yemen. In 2012, the water availability per capita was assessed to be as low as 86 cubic meters per year, one of the lowest in the region. This chronic water scarcity has had profound impacts on agriculture, as one third of the population works in small-scale subsistence farming. Agriculture yields for essential crops like wheat, maize, and vegetables have been significantly reduced; this has decreased household incomes and caused alarming food insecurity.

Some 19 million people in Yemen are grappling with food insecurity and lack access to safe and drinkable water; nearly 60 percent of these people are women and girls. In addition, about 2.5 million children under the age of five and 1.5 million pregnant and lactating women suffered from acute malnutrition over the course of 2022.

Through almost one decade of consistent armed conflict, water has become both a weapon and casualty of war. Due to its scarcity, water has been used as a military target; attacks on water infrastructure and supply chains have taken a devastating toll on local communities, particularly women and girls because they are usually responsible for collecting water for their families. As water sources decrease, women have to walk longer distances, with a high likelihood that they may step on landmines or encounter gender-based violence. In addition, girls are forced to drop out of school to take care of increased household responsibilities and unpaid domestic activities.

Additionally, about 4.5 million Yemenis have been internally displaced; roughly 70 percent are women and children. Fifty percent of them have ended up in makeshift sites that not only lack basic services but are also located within 5 kilometers of active conflict zones, disproportionately exposing them to the dangers of armed conflict.

Environmental problems are also destabilizing southern Iraq—especially Basra; in 2018, water scarcity, coupled with the government mismanagement of water quotas, instigated confrontations between southern tribes which then escalated into armed conflicts. In 2021, an acute drought resulted in the reduction of water flows in the Tigris River by 29 percent and the Euphrates River by 73 percent. A subsequent survey examining 7 Iraqi governorates revealed that 37 percent of wheat farmers and 30 percent of barley farmers suffered crop failure, which resulted in shrinking incomes (particularly for women) and alarming food insecurity among farmers’ families. As climate change continues to exhaust resources and aggravate socio-economic and political tensions, an estimated 3,000 families—including women-headed households—have been displaced across central and southern Iraq.

Water scarcity has also been a chronic challenge for Gaza and its 2.3 million inhabitants since October 7. The World Health Organization indicates that the share of water for each individual is less than a gallon per day; 20 gallons is the minimum needed for proper hygiene.

About 90 percent of Gaza’s water is pulled from groundwater wells, primarily the Coastal Aquifer Basin. In 2018, the World Bank reported that this coastal aquifer had come under increasing pressure from rising sea levels and infiltration of salt water. This problem is currently exacerbated by the war on Gaza; reports from UNICEF indicate that Israeli airstrikes have been targeting water infrastructure and desalination plants, cutting off access to aquifers in the Strip. This has caused Gaza’s water production capacity to drop to 5 percent of typical levels. In addition, it is reported that Israeli forces have razed 22 percent of farms and agricultural land in northern Gaza, leading to a significant decrease in local agricultural production and worsening malnutrition among the 300,000 people still living there, particularly pregnant and lactating women.

The deteriorating securitarian conditions, coupled with the dire climate conditions, are exacerbating the challenges of water scarcity, food insecurity, and forced displacement. Of all the people facing catastrophic hunger or famine worldwide, Gazans alone account for 80 percent percent; the majority of them are women and children.

Recognition of Female Farmers: Women as Landowners and Not Casual Workers

Since climate change is not a gender-neutral experience, governments in the MENA region must ensure that women are playing an active role in discussions on environmental policy and are receiving adequate support at the institutional, legal, and financial levels.

As previously explained, the agricultural sector is the largest employer of women in the MENA region. Women have developed significant knowledge and skills related to the collection and storage of water, the preservation and rationing of food, and the prediction and mitigation of natural disasters. However, women also suffer from dangerous working conditions, crop failures, unstable incomes, lack of health insurance and social protection, discriminatory laws, and regressive cultural norms that obstruct their land ownership.

Government authorities need to advance the legal and social recognition of women’s contributions to the agriculture sector through the gathering and analysis of gender-disaggregated data on the opportunities and constraints faced by female farmers. This will help to design policy frameworks that eliminate women’s marginalization, make their voices equally represented, and protect their legal right to land titling and management. This goal is achievable: in Morocco, female farmers formed women-led cooperatives to mobilize for better wages and working conditions. These organizations pool resources and help increase their members’ access to credit and non-land assets such as livestock, equipment, and technology. Such promising initiatives need to be integrated in other countries throughout the region.

Protecting and Empowering Women Migrants: Legal Mechanisms and Economic Opportunities

Women who are displaced by climate crises are facing a gap in protection. While the guidelines suggested by international organizations have the potential to help internally-displaced climate migrants, they remain non-binding. Thus far, these guidelines have not been effectively integrated into local legislation and where this legislation is present, it rarely addresses the issue of gender.

Some countries in the MENA region have already made commitments through their National Action Plans to secure the human rights of women and girls, particularly in conflict settings. For example, countries such as Iraq, Tunisia, Sudan, Palestine, Yemen, and Lebanon have adopted 1325 National Action Plan that entails taking special measures to protect women and girls from all forms of gender-based violence that is particularly widespread during times of violent conflict. However, there is still no unified and comprehensive regional framework for cross-border migration that provides adequate protection to vulnerable groups—particularly women—during the migration journeys and in the post-migration phase.

MENA governments should aim to provide regular and safe pathways for women that have been displaced by climate disasters, informing migrants in advance about the living conditions in destination areas, such as the availability of assistance, legal protections, and work opportunities. This will enable migrants to proactively decide if, when, and where they migrate. Equally important, governments need to create comprehensive and effective mechanisms that criminalize gender-based violence against refugees, particularly at entry points and refugee camps.

Women and Peace-Making: Women are Not Mere War Victims

While addressing the immediate impacts of climate change on women is key, it is important to remember that environmental hazards are also a political problem. As explored above, the MENA region is conflict-plagued; an alarming number of people migrate as a result of a pernicious confluence of violence, deteriorating socio-economic conditions, and escalating climate hazards. These problems are worsened by a global disinterest in advancing peace in the region.

If women are to be protected, the international community must stop these armed conflicts; if the international community wishes to stop these armed conflicts, it must challenge the global structure of militarism. In 2023, the world military expenditure reached an all-time high of $2443 billion, marking nine years of consecutive rise. The MENA region bore the biggest military burden that year; 4.2 percent of the region’s GDP was put toward military spending, double the global average. The soaring value of military expenditures—amid a global economic downturn and accelerating environmental disasters—indicate that we have built our societies to fight wars, not promote peace.

Furthermore, we need to speak differently about women in this war-torn region. Rather than being presented as peace builders, women are often portrayed only as war victims. This is understandable, given that women are still significantly underrepresented in peace processes. In the UN, only 13 percent of negotiators, 4 percent of signatories, and 3 percent of mediators between 1992 and 2018 were women. However, in order to change these realities, we must begin to recognize the contributions that women have made to peace, enable them to join negotiations, and support their ability to bring change.

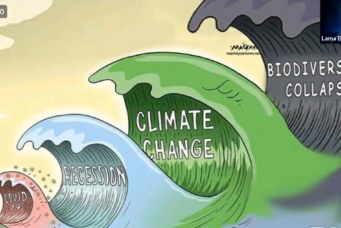

We need to amplify a narrative that treats climate change as an emergency which is quickly approaching its damaging tipping point sooner than expected. This sense of emergency is crucial in mobilizing collective efforts to stop the climate breakdown. It is equally important to stress that war is not just a tremendous waste of resources that could be used to accelerate climate action, but is itself a significant reason behind the environmental harm that falls disproportionately on marginalized groups, notably women. Therefore, women and other marginalized groups need to voice their grievances, share their lived experiences, actively lead climate action, and shape the peace-making processes in their communities. Only then we can speak about achieving climate justice for all and building sustainable peace.