After the Fall of Saigon

The Vietnam War lasted twenty years and cost the lives of more than two million Vietnamese and 58,000 U.S. troops. In the forty years since the Communist victory and American defeat, a surprising friendship has followed.

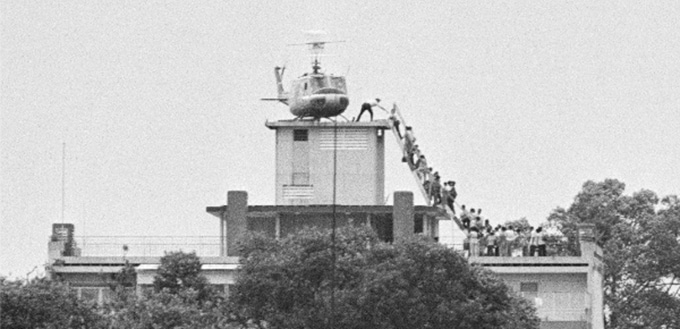

Evacuation from a U.S. embassy building, Saigon, April 29, 1975. Hubert Van Es/Bettman/Corbis.

The Vietnam War or Second Indochina War—known in Vietnam as the American War—was one of the most destructive conflicts in history, and ended with a triumphant victory for Ho Chi Minh’s Communist forces and the most humiliating military defeat the United States has ever experienced. If a single image represents the historical drama, perhaps it is the one of the Huey helicopter evacuating American personnel and Vietnamese associates from a U.S. embassy building rooftop. Ho’s Communist forces and their southern allies in the National Liberation Front had succeeded in toppling the U.S.-backed southern government of the Republic of Vietnam, and driving American troops, numbering a half million at the peak of the war, out of the country. The conflict between 1955 and 1975 left more than two million Vietnamese dead, and some 58,000 American troops perished.

Outside Vietnam, it is sometimes forgotten that the United States had also been deeply involved in the First Indochina War from 1946 to 1954, and would also become involved in the Third Indochina War from 1979 to 1989. These three wars brought enormous physical, economic, social, and moral dislocation to Vietnam, and caused deep antagonism between the governments of Vietnam and the United States as well as polarization among the Vietnamese themselves.

Forty years after the Fall of Saigon it may seem surprising that the United States and Vietnam have not only reconciled but their bilateral relations are thriving in many respects. And the Vietnam-United States rapprochement has helped foster a growing reconciliation among bitter Vietnamese adversaries, too.

On September 2, 1945, before a half million people in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh declared independence from France four days after announcing the establishment of the Provisional Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV). Most of the country was behind Ho and his revolutionary government. Emperor Bao Dai had abdicated in favor of Ho and moved from Hue to Hanoi to serve as supreme advisor to Ho and his government for almost a year.

Vietnam had struggled for centuries against Chinese domination and, later, French colonialism. By the 1880s, France controlled Vietnam and created industries for the export of rubber, tobacco, coffee, tea, and other products. Ho Chi Minh, a Communist who had developed his political thinking in Paris and Moscow, led the Viet Minh, or League for the Independence of Vietnam. Its aim was to fight against French colonialism and, after France’s capitulation to Nazi Germany, against the Japanese occupation of Vietnam.

Vive La France!

Despite Ho’s declaration of independence (which seemed conspicuously modeled after the American Declaration of Independence), and the Viet Minh’s cooperation with U.S. forces against Japan during World War II, the United States (along with Great Britain) ferried French troops to Vietnam in late 1945 to re-establish French colonialism. A key factor was Washington’s desire after the liberation of France to shore up the government of Charles de Gaulle with the resources from the richest former French colony—and head off any chance of Communists coming to power in Paris.

Armed with American weapons and supported by British troops, the French re-conquest of Vietnam began with an attack on Saigon on September 22, 1945. Within a few years, the United States and France were framing the escalating conflict as a war against Communism. In 1949, Bao Dai became chief of state of the newly formed French-controlled State of Vietnam centered in Saigon. In March 1954, however, the Viet Minh guerrilla army mounted a spectacular offensive against the French fortification at Dien Bien Phu, handing France one of the worst defeats in military history. “Vive la France!” were the last words of the final radio transmission from the French headquarters as it was being overrun. The humiliation led to the collapse of the French colonial administration in Vietnam, the end of the French Indochinese Federation of which Vietnam was a part, and the rise of other anti-colonial movements against France elsewhere. Some 2,200 French troops were killed in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and another 6,500 were taken prisoner; some of those Prisoners of War (POWs) died in captivity. The First Indochina War resulted in the deaths of a half million Vietnamese—and about 35,000 French troops—and severe economic destruction and social dislocation.

This war formally ended in July 1954 with the Geneva Conference, which resulted in the Geneva Agreements and a Final Declaration. The agreements established a ceasefire demarcation line at the 17th parallel to separate Ho’s Viet Minh forces (the coalition of many anti-colonial groups) in the North from French and Vietnamese allied forces in the South. Article 14 detailed the provisions for political and administrative control in the two regrouping zones pending the general elections to reunify the country. The Final Declaration provided for a general election in July 1956 to reunify Vietnam.

To the Viet Minh, the Geneva Agreements represented an opportunity to win over the whole country through an election and finally secure Vietnam’s independence. The Viet Minh’s hopes were raised because a definite date for the election had been set forth in both a bilateral armistice agreement with France as well as in the Final Declaration, and also because of the publicly positive stance taken by the United States at the time.

The Geneva Agreements were signed by the DRV, France, Britain, the Soviet Union, Cambodia, Laos, and the People’s Republic of China, although not by the State of Vietnam or the United States. Yet the American chief representative at the negotiations, Under Secretary of State Walter Bedell Smith, a senior U.S. army general in World War II and former head of the Central Intelligence Agency, issued a Unilateral Declaration indicating that the United States would abide by the accords. “In the case of nations now divided against their will,” Smith said, “we shall continue to seek to achieve unity through free elections, supervised by the United Nations to ensure that they are conducted fairly.”

However, because the Geneva Agreements met the essential political objectives of the DRV it became a bitter pill for the United States to swallow. According to “United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense,” better known as the Pentagon Papers, “When, in August, papers were drawn up for the National Security Council, the Geneva Conference was evaluated as a major defeat for U.S. diplomacy and a potential disaster for American security interests in the Far East.” Various plans for direct American intervention in Vietnam to remedy the situation were proposed. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles was quoted as saying that U.S. intervention had become possible because “we have a clean base there [in Indochina] now without the taint of colonialism. Dien Bien Phu was a blessing in disguise.”

Dulles was intent on preventing the advance of Communism, and feared the 1956 election would hand Ho’s Communists a decisive victory. Commentator Leo Cherne wrote in Look magazine at the time: “If elections were held today, the overwhelming majority of Vietnamese would vote Communist. No more than eighteen months remain for us to complete the job of winning over the Vietnamese before they vote. What can we do?” President Dwight D. Eisenhower rejected various proposals for direct U.S. military intervention in Vietnam at that time; for example, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Admiral Arthur W. Radford advocated an expeditionary force for the Hanoi-Haiphong region. Earlier, during the siege of Dien Bien Phu, Radford, a determined anti-Communist and interventionist, had even suggested threating the Viet Minh with a tactical nuclear attack. But administration policymakers reached a “compromise” that involved setting up a “stable, independent government” in South Vietnam. This came to be known as the “Diem Solution”—the consolidation of Ngo Dinh Diem in power in Saigon, a decision that would precipitate the Second Indochina War.

A Quasi-Police State

Diem, previously Bao Dai’s prime minister, was a Roman Catholic politician known for being a fierce anti-Communist. With American backing in 1955 he deposed Bao Dai, declared himself president, and announced the formation of the Republic of Vietnam south of the 17th parallel. After the Geneva Conference, the United States took a number of steps in direct violation of the Geneva Agreements to strengthen Diem as a bulwark in the Cold War against Communism. Major General Edward Lansdale led a propaganda fear campaign encouraging Roman Catholics to flee from the North into Diem’s republic; as many as one million northerners arrived, many ferried by sea in what the U.S. Navy called Operation Passage to Freedom, bolstering Diem’s shaky base of support in a largely Buddhist country. The United States launched efforts to build up Diem’s army, which was stepping up repression as well as pacification in the rural areas.

As early as October 1954, the United States authorized a crash program to aid Diem costing several hundred million dollars annually, beginning with the consolidation of all Vietnamese troops in the French Union forces under Vietnamese command. In November of that year, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered a prompt reassignment of selected personnel and units to maintain “the security of the legal government in Saigon and other major population centers,” to execute “regional security operations in each province,” and to perform “territorial pacification missions,” according to the Pentagon Papers.

The aim of these operations was to destroy the revolutionary infrastructures in the countryside and to terrorize the population into submitting to the Saigon administration. In mid-1955, soon after the last Viet Minh units had regrouped to the North under the Geneva Agreements, the Diem regime launched a nationwide “Communist Denunciation Campaign” in which the population was forced to inform on revolutionaries and their sympathizers. In May 1956, the Saigon regime officially announced that more than 100,000 former Viet Minh cadres had “rallied to the government” or surrendered. Tens of thousands of others had been jailed, executed, or sent to “re-education camps.” Many of these people had been innocent civilians who had simply voiced their dissatisfaction with Diem’s “land reform” program that in effect sent landlords back into the countryside to reclaim lands the revolution had parceled out to the peasants during the resistance against the French. As American foreign policy analyst William Henderson wrote in the January 1957 issue of Foreign Affairs: “South Vietnam is today a quasi-police state characterized by arbitrary arrests and imprisonment, strict censorship of the press, and the absence of an effective political opposition. All techniques of political and psychological warfare, as well as pacification campaigns involving extensive military operations, have been brought to bear against the underground.”

For their part, DRV leaders in Hanoi sought to restrain their cadres in the South, hoping that the general election and other stipulations of the Geneva Agreements could still be carried out. But Diem blocked the election, arguing that his government was not a signatory to the Geneva Agreements and thus was not bound by them. In an overall assessment of the war issued in 1995, the Vietnamese Communist Party said that the lack of a resistance strategy led to steep setbacks in the South during this time. To avoid losing influence over the southern revolutionary movement, in 1960 Hanoi sanctioned the establishment of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam—usually referred to as the National Liberation Front (NLF)—representing twenty political, social, religious, and ethnic groups, all modeled on the Viet Minh movement that had fought French colonialism. The front’s program called for the overthrow of the Diem administration, liquidation of all foreign interference, human rights and democratic freedoms, a “land to the tiller” policy, an independent economy, the establishment of a national coalition government, a foreign policy of peace and neutrality, and peaceful reunification of the country. In 1961, the NLF formed the People’s Liberation Armed Forces, which proceeded to deliver significant military blows to Diem’s forces.

Confronted with mounting pressures and on the advice of his brother and chief political advisor Ngo Dinh Nhu, Diem established contact with both the NLF and the DRV to seek a negotiated settlement. The French government helped set up a channel for negotiations in August 1963. De Gaulle announced that France was ready to help in creating a Vietnam that would be “independent of outside influences, in internal peace and unity and in concord with its neighbors.” There are still debates about Diem’s real intentions. But Washington’s doubts about Diem reached a point that it supported a military coup on November 1, 1963, that resulted in the murder of Diem and his brother. The move turned out to be a grave mistake, foreclosing the chances for reconciliation and leading to further deterioration of the Saigon regime. Faced with instability in the South Vietnamese government and near catastrophic defeats of Saigon’s Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), the President Lyndon B. Johnson administration acted on General William Westmoreland’s recommendation for a greatly expanded U.S. ground combat role in the war.

The U.S. military build-up was quick and massive: more than 181,000 men by the end of 1965, around 376,000 by the end of 1966, and some 480,000 by December 1967. According to the Pentagon Papers, Westmoreland’s forces found themselves “fighting a war of attrition.” The aim was to kill larger and larger numbers of the enemy through “search-and-destroy operations” and to force more and more villagers to move into areas controlled by the South Vietnamese government to deprive the NLF of popular support. This was known as the pacification program, or “The Other War: The War to Win Hearts and Minds.” In reality, it created enormous resentment, and consequently resistance, from the Vietnamese. By mid-1967, the U.S. Operation Mission reported that the Saigon government controlled only 168 hamlets of a total of 12,537 in South Vietnam. On the other hand, the NLF controlled 3,978. The rest were listed as “contested” or partially controlled by both sides. The U.S. Hamlet Evaluation System admitted that to a large extent the NLF dominated the countryside.

Peace with Honor

In January 1968, North Vietnamese troops and southern NLF guerrillas mounted a massive surprise offensive known as the Tet Offensive—a reference to the timing of the attack at the start of the Vietnamese New Year. Some 80,000 troops and guerrillas carried out hundreds of strikes throughout South Vietnam, even managing to briefly penetrate the American embassy in Saigon. The Communist forces suffered huge losses and failed to ignite a popular uprising in the South against the U.S.-backed regime. But they scored a major political victory by discrediting the Johnson administration’s optimistic assessments of its war effort. Two months later, his presidency in tatters due to the political fallout from Tet and the growing anti-war movement in the United States, Johnson proposed peace talks to end the conflict and announced he would not seek re-election. The Paris Peace Talks began in May but failed to achieve any results for the remainder of Johnson’s term in office.

The administration of Richard M. Nixon, the winner of the 1968 presidential election, showed little interest in the Paris Peace Talks. His national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, conducted secret negotiations starting in 1969 but they failed to yield results. Meanwhile, Nixon put into effect the “Vietnamization” program. This involved the massive build-up of Saigon forces—in effect, to encourage Vietnamese to kill other Vietnamese with the aim of preventing a total Communist takeover. It cost the United States $38,000 to send an American to Vietnam to fight for one year. But it cost an average of only $400 to support an Asian—including Korean and Thai mercenaries. Saving American lives and dollars was aimed at persuading the American public that the war was winding down. W. Averell Harriman, who Johnson sent to head the American delegation to the Paris Peace Talks, denounced Vietnamization as “a program for the continuation of the war… Vietnamization of the war is dependent on an unpopular and repressive government.”

The Nixon administration was able not only to prolong the war for five more years but also to escalate it through aerial bombing, which averaged about 100,000 tons of explosives a month on South Vietnam in 1969 and 1970—the administration halted U.S. bombing of the North as part of its peace talks diplomacy. An equal amount of high explosives was also delivered by artillery strikes monthly, which in many cases caused more systematic damage than the aerial bombardments. In April 1971,Look magazine reported on the destruction of dams, dikes, and canals, and mile upon mile of “rice fields pockmarked with millions of large craters filled with water in which malarial mosquitoes have been breeding in epidemic numbers.” These high explosives, combined with chemical spraying (which the Pentagon admitted in 1969 was limited only by the ability of the United States to produce it), had by the end of 1970 destroyed about half of the crop land in South Vietnam. This caused serious shortages of food and forced the Saigon regime to import huge amounts of staples.

The devastation and widespread hunger in the countryside drove millions of the rural population into urban areas and camps for displaced persons. The plight of these refugees was among the reasons behind the hundreds of demonstrations staged every month by scores of civic groups, which in 1970 formed the People’s Front in Struggle for Peace. The front issued a ten-point platform headed by the demand “that the Americans and their allies withdraw completely from Vietnam as the most important precondition for an end to the war.” The urban movement of groups from the right to the left became known as the third segment, or Third Force.

Mounting political pressure from the Third Force, the unraveling of the Vietnamization program, and related U.S. military setbacks in Cambodia and Laos in 1970 and 1971, respectively led the United States to sign the Paris Peace Accords of 1973. The agreements recognized the territorial integrity and unity of Vietnam, stipulated the withdrawal of U.S. forces and release of POWs, and clearly called for negotiations between the Saigon regime and its southern opponents in the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) toward a political settlement in the South and an eventual reunification of Vietnam “through peaceful means.”

Nixon described the deal as “peace with honor.” Nonetheless, the Nixon administration and the South Vietnam government of President Nguyen Van Thieu believed that carrying out the accords would lead to an eventual political takeover by Vietnamese revolutionaries. Not long after the agreement was signed on January 27, 1973, Thieu reiterated—with American acquiescence if not outright support—his “Four Nos” policy: no recognition of the enemy, no coalition government, no neutralization of the southern region of Vietnam, and no concession of territory. In a July 1973 interview in Vietnam Report, the English-language publication of the Saigon Council on Foreign Relations, Thieu stated: “In the first place, we have to do our best so that the NLF cannot build itself into a state, a second state within the South.” In the second place, he continued, his government should use all means at its disposal to prevent the development of the Third Force, branding all Third Force personalities as pro-Communist.

Arrests of Third Force activists soared and attacks on PRG-controlled areas by the Saigon regime increased partly because of increased military aid to Saigon after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords. The United States supplied the Thieu government with so many arms that, as Major General Peter Olenchuk testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee in May 1973, “We shortchanged ourselves within our overall inventories. We also shortchanged the reserve units in terms of prime assets. In certain instances, we also diverted equipment that would have gone to Europe.”

In fiscal year 1974, Congress gave the Saigon regime $1 billion more in military aid. Saigon expended as much ammunition as it could—$700 million worth. This left a stockpile of at least $300 million. For fiscal year 1975, Congress again authorized $1 billion in military aid, but appropriated $700 million—about what was actually spent in 1974. The Paris Peace Accords stipulated that equipment could only be replaced on a one-to-one basis. The February 16, 1974, edition of the Washington Postquoted Pentagon officials as saying that Thieu’s armed forces were “firing blindly into free zones [PRG-controlled areas] because they knew full well they would get all the replacement supplies they needed from the United States.” But it was the beginning of the end. Thieu’s aggression helped drive a counteroffensive by the Communist forces that brought about the fall of one southern province after another in early 1975 without too much resistance from Thieu’s forces.

Good Relations with the United States

Communist forces rolled into Saigon on April 30, 1975, and General Duong Van Minh, who had become South Vietnam’s leader following Thieu’s resignation on April 21 and subsequent escape to Taiwan, surrendered to a North Vietnamese officer at the presidential Independence Palace. This decision should have saved a great deal of unnecessary bloodshed. But, by pushing for a military solution until the very end, the United States and the Thieu regime had foreclosed the possibility for a coalition government of “reconciliation and concord” that might have prevented or eased the tumultuous political transition that ensued. Worse still, the military victory eventually justified a “winner-takes-all” mentality by opportunists, many of them carpetbaggers from the North, which made the process of internal Vietnamese reconciliation more complicated and difficult.

Even at this stage, there were still some reasons to hope that a foundation could be laid for reconciliation and political accommodation. In repeated statements, Vietnamese officials in the North and in the South said that they desired diplomatic cooperation and good relations with the United States. A few days after the liberation of South Vietnam, for example, Premier Pham Van Dong of the DRV sent a message to Washington through Sweden in which he stated that a chapter had been closed and that Hanoi was looking forward to enjoying “good relations with the United States.” In this letter Dong never touched on the subject of America’s “contribution to healing the wounds of war” as stipulated in the Paris accords—the idea of paying war reparations would have been political suicide in Washington. On May 14, 1975, on the very day that Henry Kissinger (now secretary of state) punitively extended a trade embargo against Vietnam under the Trading with the Enemy Act, the Washington Star reported that Hanoi wanted good relations with the United States and was willing to welcome, without any precondition, an American diplomatic mission in Saigon under a new South Vietnamese government.

Before the collapse of the Saigon regime in 1975, both the government in Hanoi and the PRG in the South had often stated that they envisioned the reunification of Vietnam to proceed step by step over a period from twelve to fourteen years. Hence, the Vietnamese sent two official observer delegations to the United Nations, one representing North Vietnam and the other representing the South. In mid-July, when the Vietnamese sought full membership in the United Nations, North and South Vietnam respectively submitted separate applications for membership as two independent states. The United States strongly opposed these applications.

The negative posture of the United States had the affect of strengthening the hands of the hardliners in North Vietnam who favored early reunification with the South. A longer period of reunification would have allowed the people in the South to run things their own way and to have time to establish some kind of coalition of forces in the South that would help the process of reconciliation and political accommodation there. If and when the North and the South finally reunified, the two separate political entities would have to negotiate on more or less equal terms. In fact, the South, under a neutralist and more democratic regime might have become a dynamic leader in the process. As it turned out, northerners took over and ran roughshod over the South.

Hence, nearly two months after the U.S. vetoed the applications of the two Vietnams as independent members of the United Nations, the Central Committee of the Communist Party declared at its Twenty-Fourth Plenum in September 1975 that Vietnam had entered a “new revolutionary phase” and that the tasks at hand included: “To complete the reunification of the country and take it rapidly, vigorously, and steadily to socialism. To speed up socialist construction and perfect socialist relations of production in the North. And to carry out at the same time socialist transformation and construction in the South… in every field: political, economic, technical, cultural, and ideological.” Reunification took place on July 2, 1976, with the formation of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Despite the withdrawal of all American forces from Vietnam, Washington would come to be indirectly involved in the Third Indochina War. By mid-1975, Chinese troops and the military forces of Cambodia’s Pol Pot regime, wary of Vietnam’s ambitions in Indochina, had already massed along Vietnam’s northern and western borders and carried out almost daily attacks. The new threat to the country led the Vietnamese government to add 300,000 to 400,000 men and women to the various armed forces, and implement programs for the “socialist transformation and reconstruction in the South.” This was done with an eye to maximizing the procurement of resources, taking economic and human resources (foodstuffs, able bodies, etc.) for fighting the war, especially from the rural areas to defend the country. The southern population and even some southern revolutionary leaders resisted these programs; many such leaders were purged and their supporters marginalized, creating North-South polarization among revolutionaries that had not been present before the end of the war.

The Hanoi leadership hoped that it could improve relations with the United States by offering to drop its precondition for economic aid and agreeing to resolve the issue of U.S. Missing in Action (MIA) forces. On July 31, 1978, Premier Pham told an American delegation to Hanoi led by Senator Edward Kennedy that Vietnam put aside its preconditions because Vietnam truly wanted to be a good friend of the United States. Kennedy called on the President Jimmy Carter administration to establish diplomatic relations with Vietnam, lift the trade embargo, and give Vietnam aid “according to the humanitarian traditions of our country.” Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke met the Vietnamese foreign minister at the United Nations in September 1978 and agreed on normalization without any preconditions. President Carter’s national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, wrote in his memoirs how he scuttled the move toward normalization due to the war between Vietnam and Cambodia, the close ties between Vietnam and the Soviet Union, and the continued flood of refugees from Vietnam.

In early November 1978, fearing that Washington’s tough stand would encourage China and Cambodia to stage a pincer attack on its territory, Vietnam signed a treaty of friendship and mutual assistance with the Soviet Union. On December 15, the United States announced a historic normalization of relations with China—ending a hostility that dated back to Mao Zedong’s revolution in 1949. On December 25, Vietnam launched a preemptive invasion of Cambodia and overthrew the Khmer Rouge government—its official explanation was to save the Cambodian people from the genocidal Pol Pot regime. During a visit to the United States in January 1979, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping announced that China would “teach Vietnam a lesson” and asked President Carter for “moral support” for the forthcoming Chinese punitive war against Vietnam.

In February 1979, China launched an invasion that nearly destroyed six northern Vietnamese provinces and, by China’s estimate, killed 75,000 Vietnamese defenders. For the next ten years, China and the United States supplied military equipment to the remnants of Pol Pot’s forces and applied the maximum economic and diplomatic pressure on Vietnam. By 1989, Vietnam had withdrawn all its forces from Cambodia, and in 1991 signed the UN-sponsored settlement for Cambodia. In 1992, China established full diplomatic relations with Vietnam after extracting many concessions from Vietnam’s top leaders. It is worth noting that American support for China during this period had the effect of sending Vietnam deeply into China’s sphere of influence, especially following the collapse of the Soviet Union. In playing the “China card,” the United States pushed Vietnam increasingly into China’s arms and gave China the opportunity to penetrate deeply into every aspect of Vietnam’s political, economic, and social life.

There Is Nothing Impossible

After decades of enmity between Washington and Hanoi, normalizing relations was a daunting challenge. But for Vietnam, the time was ripe because of its need to rebuild its economy after the destruction left by a half century of conflict, and the need to balance its strategic relations following the demise of the Soviet Union and the hostility of its other erstwhile Communist ally, China.

In 1994, the United States finally lifted its trade embargo on Vietnam. The official sticking point had been U.S. insistence that Vietnam account for the 1,677 American servicemen still listed as MIA in Indochina. This was an issue that the anti-Vietnam and anti-Communist lobbies in the United States had concocted to prevent improved relations. To symbolize this hot-button domestic political issue, Clinton named as America’s first ambassador to Vietnam Douglas (Pete) Peterson, a former Air Force fighter pilot who had spent six and a half years as a prisoner of war in Hanoi.

But Washington clearly saw the geopolitical benefits of improved relations with Vietnam in light of China’s emergence as an economic and military power in Asia. One of America’s concerns had been China’s hegemony in the South China Sea—Vietnam’s coastline covers almost the entire length of a body of water through which about 60 percent of the world’s seaborne trade passes annually.

The first items on the agenda of these new bilateral relations involved various issues left over from the Second Indochina War. These included accounting for the American MIAs, reuniting the families of Vietnamese refugees, and humanitarian programs such as the clearing of unexploded mines and cluster munitions and the cleanup of land areas contaminated by toxic chemicals such as Agent Orange that continued to cause birth defects, cancer, and other health problems.

Senator John McCain, another former POW in Hanoi, and many American veterans such as John Kerry, the current secretary of state, Peterson, and subsequent U.S. ambassadors to Vietnam have patiently and courageously worked to defuse the very emotional and difficult MIA issue. Joint American-Vietnamese search teams have combed the country for possible remains. At times they dug in the middle of Vietnamese villages and graveyards just because of some rumors. Hanoi has also actually opened its secret records of those captured to American researchers.

American veterans and volunteers have worked with Vietnamese counterparts to build friendship and trust on the issues of unexploded ordnance and remediation of residual effects of herbicides, particularly Agent Orange. Until very recently, various U.S. administrations have looked at these problems as “humanitarian” issues and have been content to let American and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) take the lead.

In spite of studies documenting the harmful lingering effects of Agent Orange, the U.S. government officially refused to recognize the problems created in Vietnam fearing that the Vietnamese would link the issue to war reparations. But in 2005, military-to-military cooperation began tackling dioxin remediation. In 2006, as Vietnam prepared to enter the World Trade Organization and as the United States and Vietnam were recognizing certain shared interests with respect to China and terrorism, then-U.S. Ambassador Michael Marine publicly called for progress on the issue of Agent Orange. In November, when President George W. Bush visited Hanoi to participate in an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting, a joint statement issued by the two governments said that their respective presidents “agreed that further joint efforts to address the environmental contamination near former dioxin storage sites would make a valuable contribution to the continued development of their bilateral relationship.” A Congressional allocation of $3 million for remediation in 2007 was followed by similar allocations for fiscal years 2009 and 2010, for a total of $9 million. Then came a Ford Foundation initiative, the U.S.-Vietnam Dialogue Group on Agent Orange/Dioxin. In June 2010, the group released a ten-year, $300 million plan of action to clean dioxin-contaminated soil and restore damaged ecosystems and expand services to people with disabilities and their families.

Meanwhile, according to various U.S. estimates, the end of the war left about 25 million pounds of unexploded ordnance in the southern part of Vietnam alone; since 1975, buried bombs have killed 40,000 people nationwide and injured 60,000, nearly half of them children below the age of 16.Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Rose Gottemoeller visited Vietnam in 2015 and announced that the U.S. government would spend $10 million on programs to survey and clear unexploded ordnance this year. American non-governmental organizations have spent $80 million on such programs in Vietnam over the last twenty years.

The results of improved ties are impressive. Trade between the United States and Vietnam grew from less than $500 million in 1995 to $35 billion in 2014. Charlene Barshefsky, the former United States Trade Representative, stated in prepared remarks delivered to the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam in Hanoi in March 2015 that since the signing of the Bilateral Trade Agreement between the two countries in 2000, Vietnam has been the fastest growing of America’s fifty largest trade relationships. She said that most of this has been import growth, up from $800 million worth of coffee and shrimp in 2000 to $30 billion in clothing, furniture, consumer electronics, shoes, fish, rice, and processed foods in 2014. Americans bought more from Vietnam in 2014 than from some much larger countries including Russia and Brazil, for example. As of 2014, Vietnam had surpassed Malaysia and Thailand to become the top merchandise exporter to the United States among the countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Barshefsky hailed Vietnam’s progress and underlined America’s interest in supporting future economic development. Since Vietnam signed the Bilateral Trade Agreement and subsequently entered the World Trade Organization, its economy has tripled in size and its per capita income has doubled. Since 2000, she noted, the national rate of deep poverty has dropped from about 45 percent to 2.4 percent—“a remarkable achievement, lacking many parallels elsewhere in the world.” She said that 17,000 Vietnamese college students were studying in the United States, as many as from Canada and more than from Mexico or the United Kingdom. “There is every reason to believe that they will help Vietnam change as rapidly, and advance as quickly, as their elders did in the last fifteen years,” she said. “And that as their lives and careers advance, they will continue to build a closer and more interrelated relationship between our two countries.”

Ted Osius, the current U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, is equally bullish in remarks that would have been almost unimaginable twenty-five years ago. In January, at a conference called “Vietnam-United States Relationship: For 20 More Successful Years,” Osius reviewed significant achievements and promised further collaboration. He said that after the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is signed—possibly in 2015—he expects the United States to become the top investor in Vietnam. The TPP is a complex project for rebalancing the United States toward Asia that includes not just trade but also security and development in the decades to come. Osius told the audience at the National University in Hanoi that the relationship between the United States and Vietnam is regional and global and not just bilateral. He listed areas of cooperation such as security, science, technology, health, private enterprises, human rights, culture, sports, and especially education. He punctuated his remarks with the refrain: “There is nothing impossible in the relationship between the two countries.” This was met with huge applause every time it was repeated, perhaps because it seemed to echo the famous slogan by Ho Chi Minh during his independence speech in 1945: “There is nothing as precious as independence and freedom.”

Return of the Viet Kieu

The improved relationship between the United States and Vietnam has had another beneficial result: mitigating the antagonism within the Vietnamese refugee communities in the United States toward the Vietnamese government and thereby aiding the process of reconciliation between bitter adversaries. Both governments made efforts to reunite families through the Orderly Departure Program and enabling visits to Vietnam by the Viet Kieu, or “Overseas Vietnamese.” There are about four million ethnic Vietnamese residents in 101 countries, with nearly 1.3 million living in the United States.

There have been three waves of Vietnamese immigration to the United States. The first wave began in 1975 when the Fall of Saigon led to the American-sponsored evacuation of Vietnamese military personnel, bureaucrats, and urban professionals, and their family members. By the end of 1975, the number of these evacuees reached about 125,000. A second wave entered the United States in the late 1970s as so-called “Boat People”—Vietnamese fleeing in rickety vessels on dangerous seas to escape political or ethnic persecution as well as the terrible consequences of the wars with Cambodia and China. According to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), the population of Vietnamese refugees in the United States increased from almost 231,000 in 1980 to nearly 1.3 million in 2012, making it the largest foreign-born population in the country. Migration since has mostly consisted of immigrants reuniting with their relatives in the United States.

Whatever the reasons for their migration, there is no doubt that the normalization of relations between the United States and Vietnam has encouraged more Vietnamese immigrants in the United States to visit their families in Vietnam. In 1993, close to 153,000 of these people returned to Vietnam for visits. In 2003 there were 380,000, and in 2005 nearly half a million. In 2007, to encourage even more returns, the government began granting Viet Kieu visa exemptions for up to ninety days per visit. The number of visits has remained around 500,000 a year in the past five years. Assuming that the visitors spend an average of only about $1,000 each during their stays, this would have brought in about half a billion dollars annually to the local economy.

More contact has also induced more investments and remittances. Statistics given by the Committee on Overseas Vietnamese and printed in many daily newspapers in February 2015 said Viet Kieu had been involved in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in 3,600 projects in fifty-one out of sixty-three provinces and cities in Vietnam. The combined amount of investment in these projects was $8.6 billion by the end of 2014, or equal to half of the entire FDI investment for the year. Presumably, many more investment projects have been indirectly funded by the Viet Kieu through remittances and run by family members living in Vietnam.

Remittances increased from $1 billion in 2000 to $9 billion in 2013, according to information from the Asian Development Bank and the National Bank of Vietnam. There was a significant jump from under $4 billion in 2005 to $6 billion in 2006 and $7 billion in 2007. Perhaps because of the global financial crisis in 2008 there was a retreat to $6 billion. According to MPI, total remittances sent to Vietnam via formal channels equaled $11 billion in 2013, representing about 6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), according to data from the World Bank. The report says that immigrants in the United States transferred about $5.7 billion in remittances to Vietnam in 2012.

It may take another generation before the wounds can fully heal, however. Due to political pressures that remain in the Vietnamese diaspora, it has been difficult for individuals to talk publicly about the reasons for their willingness to return to Vietnam and the extent of their success there. Some of the pressure comes from within the extended family, and there is also outright intimidation by hardline anti-Communists within the overseas communities.

Political Symbolism

American interventions in Vietnam between 1945 and 1995 saw many twists and turns, but Washington’s motivations had little to do with Vietnam or the Vietnamese. U.S. involvement in the First Indochina War stemmed from its desire to help France re-establish its colonial rule, rationalized in terms of preventing the French Communists coming to power in Paris and preventing the spread of Communism to Vietnam and other parts of East Asia. The Second Indochina War became a regional hot war justified by the Cold War, pushing the Vietnamese people willy-nilly into either the “Communist camp” or the “Free World camp” without regard for the universal Vietnamese demand for independence. The Third Indochina War was a “proxy war” against the Soviet Union.

With the promising turnaround in relations, the United States must now be careful not to appear heavy-handed and self-centered in its approach lest many years of hard work would be compromised. Two sensitive and linked issues will be arms sales and human rights. In 2015, Ambassador Osius and Pham Quang Vinh, Vietnam’s ambassador to the United States, appeared on a platform in Washington to discuss bilateral relations. The Vietnamese envoy argued that the United States should lift the arms embargo on Vietnam; Osius tied the issue to progress on human rights, which he said remains the most difficult aspect of the relationship.

Human rights should be a very important concern for everyone and every nation, and abuses remain a problem in Vietnam. But the United States should not overplay its hand on human rights as it once did on the POW/MIA issue. American arms would help Vietnam share the security burdens of East Asia with the United States while appearing as a self-reliant partner and not an American puppet. As Ambassador Pham emphasized, lifting the arms embargo would achieve great “political symbolism.”

Ngo Vinh Long is a professor of history at the University of Maine, where he has taught for more than twenty-five years. He is also a research associate at Duy Tan University, Da Nang. He has contributed to the Journal of Contemporary Asia, The American Historical Review, and other publications.