Congo Stories

Conflict and population displacement in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is portrayed as impossibly complex. There are four competing accounts, depending on which side is telling the story. Interpretation of history will always be contested. A more inclusive narrative can clear the way to constructive solutions.

Congolese escaping fighting between government troops and rebels, Sake, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nov. 22, 2012. Dai Kurokawa/EPA/Corbis

Anyone paying attention to the Democratic Republic of the Congo must have a high tolerance for paradox. At times the conflict is portrayed as impossibly complex, with deep moral ambiguity; alternately, one reads simple explanations of good guys versus bad guys—innocent civilians and aid workers suffering at the hands of blood-thirsty fighters, corporate exploiters, and sexual predators. The root causes of the crises are alternately given as European colonialism, international intervention, bad governance, abundant natural resources, or tribal hatreds. Suggested policy responses also vary widely. Is it possible for an observer to untangle these stories and develop a more coherent narrative of the violence and forced population displacement?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), known as Zaire during the thirty-two-year reign Mobutu Sese Seko, has been the setting for one of the most violent conflicts in African history. In 1994, the Rwandan genocide erupted, during which ethnic Hutu extremists masterminded the massacre of up to 800,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutu. The conflict spilled over into Zaire when tens of thousands of Rwandan Hutu militants and former soldiers—génocidaires—infiltrated the massive refugee exodus. The Hutu militants proceeded to engage in cross-border violence against the new Tutsi-led Rwandan government. They also stoked ethnic conflict with local Congolese Tutsis as enmities from Rwanda spread across the border. Then, in 1996, Rwandan troops allied with anti-Mobutu rebels invaded Zaire and toppled the Mobutu dictatorship. Over the last decade and a half, the country has been convulsed by cycles of conflict involving DRC government forces, various rebel groups and foreign armies.

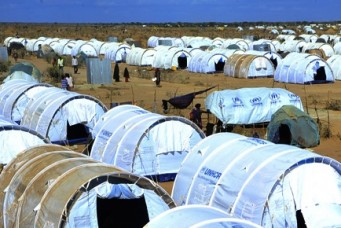

Forced displacement in the DRC has thus become one of the world’s most severe refugee crises. Related serious problems have multiplied, such as child soldier recruitment, sexual violence, and forced labor. As people leave their homes, they lose the protection of their families and their means of making a living. Violence and instability not only cause displacement but impede counting and assisting the refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Figures from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provide a snapshot of the crisis. As of September 30, 2012, there were more than 2.2 million IDPs in the DRC, mostly in South Kivu and North Kivu in Eastern Congo. (Fighting in late 2012 led to the displacement of an additional 589,000 people in these regions.) More than 450,000 Congolese live as refugees outside the country, primarily in the Republic of Congo, Uganda, Tanzania, and Rwanda. The DRC, meanwhile, hosts about 140,000 refugees largely from Rwanda and Angola.

The most significant refugee influx occurred when more than 1.2 million Rwandan Hutu refugees fled to Zaire amid the genocide. The subsequent related military conflicts resulted in additional displacement. The United Nations as well as human rights groups have alleged that Rwandan troops pursued and murdered unknown thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of Rwandan Hutu refugees following the 1996 invasion. However, most of the Hutu refugees in the DRC returned to Rwanda after this period.

Underlying the debate about the conflict and forced displacement in the DRC are storylines that describe the progression of events leading to the present. These storylines interpret history, assign blame for previous violence, identify the “deserving” displaced people, and diagnose various ills affecting political culture. Such stories are not merely propaganda, political rhetoric, or media inventions. Narratives matter because they simplify the situation in terms of positing causes and in recommending solutions. As political scientists Molly Patterson and Kristen Renwick Monroe have explained, “insofar as narratives affect our perceptions of political reality, which in turn affect our actions in response to or in anticipation of political events, narrative plays a critical role in the construction of political behavior.” In particular, narrative simplification affects international publics and even governments who lack deep context about the situation, yet who feel the desire, or pressure, to act.

There are four different narratives relevant to forced displacement issues in the DRC, most of which offer competing storylines which, in turn, prompt differing policy responses: the Rwandan security narrative; the western atrocity victim narrative; the displaced population’s agency narrative; and the DRC government regional security narrative.

It is important to note that the dominant narratives—those most readily heard and accepted by the international community—are the ones presented by outsiders: the Rwandan and Western narratives. By contrast, the DRC government has been effectively silenced, as have the actual victims of the violence. Power and narrative are closely related, which explains why the groups holding political, economic, and military advantages—Western states and neighboring Rwanda—have been able to shape the story of the conflict. For the United States, this continues a pattern established during the Cold War, when the U.S. imposed the narrative of the global struggle against Communism on domestic Zairian politics (with disastrous consequences for Zairians).

These competing narratives alternately obfuscate and clarify. Some contain outright lies; some are rife with significant omissions. They all hold some truth. Each narrative draws on different aspects and interpretations of historical memory, which often exclude or contradict the memories of other groups. Untangling those storylines in the context of forced displacement in Congo and the region is a challenging task considering the many interactions and overlaps in narratives.

Rwandan Security Narrative

Propagated by the administration of Rwandan President Paul Kagame, this narrative stresses the threat posed by the anti-Tutsi Rwandan rebels based across the border in the DRC. The 1994 genocide and resulting refugee crisis underpins Kagame’s discourse: “Our problem in Congo for eighteen years has been a security problem,” Kagame said in a TIME magazine interview published in September 2012. Kagame elaborated on his version of historical memory: “Our story starts with 1990 when our struggle started, and then in 1994, when we had the genocide and refugees running to Congo… And then you have the history of the international community and how they messed up and meddled and did all kinds of things. They were feeding génocidaires, giving them help and food in camps that were militarized. They were calling them refugee camps and you would find anti-aircraft guns and APCs and all kinds of weaponry in the refugee camps. And the world wants to tell you these are refugees.” In Kagame’s recitation, the fomenting of ethnic Hutu and Tutsi divisions by Belgian colonizers forms the historical backdrop for the 1990s genocide.

Kagame categorically rejects the DRC government narrative, which includes accusations that the Rwandan government provided support for an attack on the Congolese city of Goma last November by the Congolese rebel group known as the March 23 Movement (M23). The attack forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee the fighting, further exacerbating Congo’s refugee crisis. In a speech at the Rwanda Defence Force Command and Staff College in July 2012, Kagame declared: “Actually the problem of Congo came from outside… It was created by the international community—our partners—because they don’t listen, they are so arrogant.” The Rwandan daily New Times quoted Kagame denying any support to the M23, although he has called the group’s political grievances legitimate. “We are not supplying even one bullet, we have not and we will not,” he said.

Kagame realizes the strategic advantage gained by establishing a dominant narrative. He assured his audience at the military academy: “I am not dramatizing anything here, I am telling the real story.” In the TIME interview, Kagame used the terms “story” and “narrative” six times. Responding again to allegations of M23 support, he erupted, “I’ve never seen such a stupid story.”

Kagame’s representation of the historical memory of the 1990s is not so much inaccurate as incomplete. The Rwandan narrative does not mention (and in fact criminalizes any discussion of) violence perpetrated by forces of Rwanda’s ruling party, the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), against Hutu civilians, or the mass displacement that preceded the Hutu genocide of the Tutsis. The Rwandan narrative also omits the mass killing by RPF forces and Congolese rebels of Rwandan Hutu refugees in the DRC following the 1996 mass repatriation. The Rwandan foreign minister castigated a United Nations report detailing more than six hundred specific instances of war crimes as a “moral and intellectual failure as well as an insult to history.” The Rwandan narrative avoids discussing the history of Rwandan plundering of Congolese mineral resources.

The Rwandan version clashes with many aspects of all three competing narratives. It rejects the Western narrative that discusses the humanitarian disaster and human rights abuses of displaced people (as well as other residents) as that narrative includes criticism of Rwanda’s role in Congo. The RPF government accuses aid workers of bias and ignorance, particularly in connection with Western humanitarian aid to the militarized Rwandan Hutu refugee population in the DRC. As Kagame toldTIME: “And the problem of Rwanda, which for many years has been one of security, these murderers who live in Congo, this problem never features.” The Rwandan narrative stresses the role of other actors, such as Congolese forces and various rebel groups, in causing displacement and mistreating civilians.

Western Atrocity Victim Narrative

Western aid and advocacy groups, politicians, the media, and researchers often tell the story of a long, unbroken history of violence, poverty, poor-governance, and civilian suffering. It is a story that draws on a global atrocity narrative that homogenizes distant suffering and disasters. The plotline strings together the rapacious King Leopold and the Belgian colonizers, Mobutu’s kleptocracy, and state collapse since the 1990s. (The story tends to skip over the role of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in the assassination of independence leader and popularly elected Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961.) This narrative highlights monstrous abuses, inflicted primarily on women and children. Refugees and IDPs figure prominently as victims due to the vulnerability inherent in displacement. They are uprooted from their homes, support networks, and livelihoods, and depend on others to meet their basic needs.

Typically the story contains accounts of unadulterated evil preying on helpless, defiled innocence. Reporting from the war zone in eastern DRC in 2010, for example, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof challenged readers with excruciating tales of human suffering, such as this woman’s experience: “‘First, they tied up my uncle’ Jeanne said. ‘They cut off his hands, gouged out his eyes, cut off his feet, cut off his sex organs, and left him like that. He was still alive.’” The woman then chokes out her story of repeated sexual assaults, which “tore apart her insides and left her dribbling wastes constantly…delirious and almost dead.”

The M23 attack on Goma prompted another flurry of media accounts that reinforced the Western atrocity victim narrative. A New York Times article by reporter Jeffrey Gettleman described “a group of Tutsi-led rebels, widely believed to be backed by Rwanda, eviscerating a feckless, alcoholic government army that didn’t even bother to scoop up its dead.” The article was peppered with language such as: “Never-ending nightmare,” “a doomed sense of déjà vu,” “ambient chaos,” “blood-soaked.” It described the cannibalism, witchcraft, and primitive superstitions practiced by the various combatants. That story of the Congo is so discouraging as to leave the reader horrified and paralyzed.

An earlier story by the same journalist presented a more nuanced view of the conflict by including local perspectives. He interviewed residents who had experienced multiple displacements and did not just relate stomach-churning incidences of sexual assaults. The article also quoted a Congolese researcher on the complexity of the conflict, including the importance of local land disputes.

Perhaps portraying graphic horror is the only way to capture the increasingly fickle and short-lived attention span of international audiences. Donors and activists seem prompted to act against unambiguously wicked atrocities. Thus, humanitarian campaigns gain steam amid accounts of amputation, rape, honor killing, and forced induction of child soldiers.

Such depictions by Western journalists, humanitarian organizations and human rights groups are hardly unique to Congo. Stories of other African crises, such as Somalia and Darfur, also present a picture of misery and hopelessness. This emphasis captures part of the situation—the human suffering—but fails to explain the fuller reality as experienced by local people.

The problem is that ignoring local voices can distort Western advocacy efforts, even if the story is told with the laudable intention of rallying support for suffering victims. Political scientist Séverine Autesserre critiques the standard narratives of Congolese politics in her book The Trouble with the Congo: Local Violence and the Failure of International Peacebuilding. She finds that local explanations for and responses to conflict are more accurate than what she terms “top-down” narratives. Her recommendation to pay attention to local knowledge and bottom-up solutions will be useful for resolving the displacement crisis. If people are actually being forced off their land due to local disputes, rather than by wider conflicts between governments and rebel groups, solely the defeat of the rebels will not provide the necessary conditions for their return. A similar case can be made in addressing the problem of rape. The American Journal of Public Health has reported that rape is much more widespread in the population than has been implied in stories about “systematic rape” perpetrated by combatants. That information indicates that preventing rape will require a much broader effort than simply targeting armed groups.

Historical memory affects how humanitarian organizations approach displacement. The fact that aid workers did indeed feed and care for genocidal killers among the displaced civilians during the Rwandan refugee crisis between 1994-96 has led to much conspicuous soul-searching among humanitarians. Perhaps this helps explain a new emphasis on identifying recipients as innocent and pure. Highlighting women, children, the sick, and the elderly in publicity material will reassure wary donors who want to make sure they are not once again providing succor to genocidal killers. The risk is that the victim advocacy narrative is so successful that it convinces sympathetic, but despairing, outsiders that their efforts could achieve better results in another, less hopeless, crisis.

Displaced Population Agency Narrative

This narrative emerges from first-person accounts of displacement. Here, displaced individuals are agents who have widely varying experiences and perceptions of the crisis. Common themes in the narrative are repeated displacement, exploitation, government corruption, and abuse from nearly all parties to the conflict. In light of the condemnation of the government by locals, their concerns are largely absent from the story told by the DRC government. In other words, their voices are often drowned when they contradict more powerful actors. Alternately, the displaced may find their stories co-opted for publicity or propaganda purposes. Some organizations search for these local stories to enhance the dominant narrative.

Most Congolese IDPs are “situational refugees,” to use a term developed in my research on refugees and the spread of conflict published in Dangerous Sanctuaries: Refugee Crises, Civil War, and the Dilemmas of Humanitarian Aid. Situational refugees fled from generalized violence and threats; they have little political organization or allegiance to any of the combatant groups. The primary goal of situational refugees (as with IDPs generally) is to return home in peace and regain their means of livelihood.

The other categories of refugees based on the cause of flight are “state-in-exile refugees” and “persecuted refugees.” State-in-exile refugees are highly militarized and usually left their country as a strategy of war. The Rwandan Hutu refugees from the 1990s constituted a state-in-exile in Zaire (although many of the civilians did not participate in violence and later returned home). Persecuted refugees flee due to targeted violence or threats based on a group characteristic such as ethnicity or religion. They tend to have greater group cohesiveness than situational refugees, but have less chance of military organization than state-in-exile groups. This typology applies to internally displaced populations as well as refugees, although state-in-exile groups are more likely to cross an international border as a way to regroup for continued fighting.

The displaced population’s agency narrative spends little time on statistics and categories, however. Humanitarians, researchers, and policy makers create, and fill, categories of IDPs; newly displaced, secondary displacement, vulnerable groups, unaccompanied minors, returnees, locally integrated. They count, and dispute, the numbers overall and the numbers in each category. These statistics (100,000 newly displaced, 200,000 returned, etc.) do not capture the many multiple displacements, insecurities, and adjustments made by the war-affected civilians. A widowed Congolese mother displaced from her farm is not fixated on determining the appropriate category for her situation; her concerns are more fundamental.

Indeed, the situation fluctuates so rapidly, and people shift in and out of categories so regularly, that the international and governmental statistical focus is constantly inaccurate or outdated. In many cases, there is not a clear divide between the displaced and the non-displaced. There are many alternatives to living in camps such as crowding in with family or finding shelter without external assistance. Attackers also do not recognize a clear divide when abusing civilians. Nonetheless, the categories have an impact when aid distribution is contingent on the category to which one is assigned.

DRC Government Regional Stability Narrative

The DRC government cites two major causes of the violence: malfeasance of the former Zairean governments, and interference from external states and groups. The “bad guys” include Rwanda, international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the M23 rebels, Rwandan Hutu rebels, and the past Zairean leaders. In the Congolese government narrative, these factors, most of which exculpate the current government, account for the country’s failures and the state’s fragility. The government narrative downplays the need for democratization in the DRC, instead emphasizing the government’s responsibility in providing stability. Certainly, Congo has suffered from rapacious interveners and rebel groups. Yet, considering the almost universal reports of government corruption, cruelty, and incompetence, this narrative fails to convince most observers.

The narrative was on display when the DRC ambassador to the United Kingdom blasted the recent decision of the International Monetary Fund to suspend loans to the DRC. The ambassador explained that the debt dated back to the “corrupt Mobutu regime” and the “years of decay and civil wars.” He praised President Joseph Kabila, “who has restored democracy to DRC after years of misrule.” In common with the Rwandan narrative, the DRC government view of NGOs borders on paranoia; it blames them for spreading innuendo about corruption and other misdeeds. The ambassador accused “individuals and groups with political agendas against the government of President Kabila” of influencing the IMF’s decision.

Who is listening?

Clearly, the Congo narratives are told with the intention of engaging and persuading listeners. The implied audience is the ‘international community.’ The urgency with which the various narrators communicate indicates the perceived significance of narratives in shaping policy outcomes.

Acceptance of the Rwandan narrative would encourage negotiations with M23 and tolerance of Rwanda’s military involvement in eastern DRC. It would also validate suspicion toward returning Rwandan refugees, suggesting that they have ties to the Hutu rebel groups based in the DRC. The Western atrocity victim narrative emphasizes aid to Congo and the vast human needs in the country. Proponents of this narrative risk exaggerating hopelessness in a way that leaves the intended audience in despair. However, integration of the victim narrative with the agency narrative can enrich the humanitarian account and help improve the lives of the Congolese people. Acceptance of the DRC government narrative would endorse its accusations of Rwandan interference and downplay the need for democracy and good governance. Such acceptance would likely ignore the bottom-up suggestions of the local displaced population. In practical terms, the choice of dominant narrative will affect the policies of external actors on whether to promote negotiations with the M23 rebels, the level and type of outside aid, and whether approaches to resolving the crisis will focus solely on high politics or will take into account local disputes and problems as well.

Sole reliance on only one of these narratives will skew policy responses in ways that will likely impede resolution of the many forced migration crises in the DRC. For policy makers and journalists alike, the general tendency is to pick one narrative and stick with it. The media may go with the most dramatic plot and policy makers may opt for the narrative with least political risk.

As Séverine Autesserre points out in a 2012 essay in African Affairs, international actors prefer an “uncomplicated story line, which builds on elements already familiar to the general public, and a straightforward solution.” But the more challenging task is to assemble an inclusive narrative. Interpretation of history is contested, and always will be. Yet it is possible to appreciate multiple views. This requires listening carefully and critically to the narratives of security, victimhood, agency, and stability. And questioning dominant narratives when they silence less powerful ones. Listening can untangle the paradoxes and clear the way to constructive solutions.

Sarah Kenyon Lischer is associate professor of political science at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. She is the author of Dangerous Sanctuaries: Refugee Camps, Civil War, and the Dilemmas of Humanitarian Aid. She has published in International Security, Global Governance, Conflict, Security, and Development, the American Scholar, and the Los Angeles Times. She is currently writing a book on atrocity narratives and reconciliation after genocide.