Struggle of the Middle East Refugees

The displacement of millions of Syrians is merely the latest such crisis in the region. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees argues that the world must provide political solutions, not only humanitarian aid.

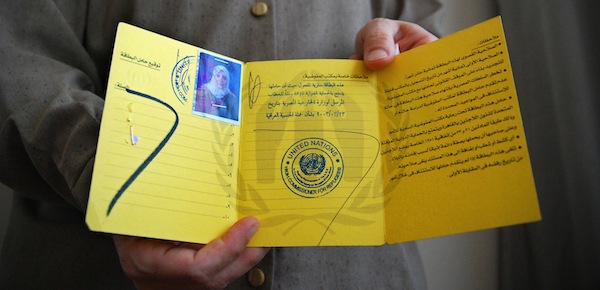

An Iraqi woman holds a United Nations refugee identity document, Cairo, Aug. 23, 2008. Adam Reynolds/Corbis

Throughout history, the Middle East has been one of the major crossroads of humanity, where continents, cultures, and ideas intersect. People have always been on the move in this corner of the world, though not always voluntarily so. Like other troubled regions, the Middle East has produced, and hosted, millions of refugees over the past decades. Two years since the beginning of the Arab Spring, a long and difficult transition period now lies ahead for the region. Its old and new refugee crises form part of the various challenges it must grapple with during this process. The Middle East’s strong tradition of hospitality and generosity towards neighbors in need will continue to be one of its most powerful assets in this effort. In order to uphold this tradition in the face of fundamental and delicate political and social change, the region will require robust support from the international community.

Exodus from Syria

Ravaged by the most complex and devastating of the world’s current crises, Syria has itself a long and generous history of providing refuge to people in need of sanctuary, including Palestinian and Iraqi refugees. This makes the current suffering the Syrians have to endure all the more heartbreaking. The horrendous bloodshed that is now entering its third year has displaced over four million Syrians internally, many of them uprooted again and again as the fighting spreads and the entire country is engulfed in violence and chaos. Their situation is extremely precarious, and without unrestricted humanitarian access to those in need, it is getting worse every day. For more and more people, becoming refugees is the only way to survive; over 1.3 million people have already fled across borders to seek safety abroad. Since the beginning of 2013, nearly 50,000 people have been fleeing Syria every week to Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Iraq. Growing numbers go even farther, to North Africa and Europe. But too many do not make it to safety, and end up trapped in war zones or dying during the perilous journey to the border.

Most refugees who do manage to cross the borders do so during the dead of night, often with nothing but the clothes on their backs, and tell gruesome stories of the hell they left behind. Once they cross into safety, they find shelter with relatives and friends, in public buildings, or rapidly growing camps. In one of the worst winters in the region in many years, humanitarian agencies race against the clock to register new arrivals and provide them with shelter, blankets and mattresses, heaters and cooking sets, food, medicines, and clean water.

Children suffer the most, and more than half of Syria’s refugees are under age eighteen. Many of them have lost parents, siblings, or friends, seen their houses and communities bombarded, and their schools destroyed. The level of trauma and psychological distress, especially among the youngest, is appalling, and despite their best efforts, humanitarian agencies do not have the capacity to respond adequately to these needs and help heal the wounds the war has left on these children’s psyches. Hundreds of thousands of young lives have already been shattered by this conflict, leaving the future generation of an entire country marked by violence and trauma for many years to come.

This conflict must stop, and a political solution must be found so as to bring peace back to Syria and its people, although in the current scenario there is little reason to hope that day is near. In the meantime, all we can do as humanitarians is to continue our appeals for civilians to be spared, and for the help we can provide to be allowed to reach those in need. Humanitarian access to the displaced, regardless of their location, continues to be the biggest challenge in the response inside Syria, along with that of finding adequate financial resources. Delivering assistance in some areas of the country is highly challenging, and the majority of humanitarian agencies were for a long time unable to access people displaced in northern Syria and other contested regions. Only in late January, was the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) able to start delivering emergency winter relief to areas north of Aleppo. Getting there requires constant close consultations with all parties to the conflict and strict adherence to humanitarian principles. The risks involved are high, but the price of not trying is even higher.

Plight of Iraqi Refugees

But Syria is far from being the only refugee situation needing attention in the Middle East. There are still hundreds of thousands of Iraqi refugees hosted in the region after a massive displacement wave was sparked by sectarian violence that started after the first Al-Askari mosque bombing in February 2006. At the height of the crisis, an estimated 2 million people had become internally displaced, and nearly as many had fled abroad, most notably to Jordan and Syria, but also to Egypt, Lebanon, Turkey, and the Gulf states. Most refugees were of an urban background and chose the region’s large cities as their place of exile.

Syria and Jordan still host the largest Iraqi refugee populations in the region. Nearly 64,000 Iraqi refugees are registered with UNHCR in Syria, and some 30,000 in Jordan. The governments of both countries estimate that there are hundreds of thousands more living in Syria and Jordan. Over the years, this added urban population has increased the pressure on the resources of both countries, with prices for oil, electricity, and water having risen by as much as 20 percent, and rents skyrocketing. Iraqi refugees cannot work legally in either country, and after having lived on their savings for as long as they could, more and more of them have grown impoverished over the years. Requesting assistance is seen by many as dishonorable and demeaning to their family’s name, and many only register with UNHCR when they become so vulnerable that they are no longer able to fend for themselves. Host countries continue to shoulder much of the burden of assisting Iraqi refugees, to provide them with access to national health and education infrastructures.

Iraqis were, and still remain, one of the largest urban refugee populations in the world. Urbanization is a dynamic process, and when Middle Eastern capitals began receiving large numbers of Iraqi refugees, the humanitarian community had not yet adjusted to this new reality, having worked mainly on the basis of traditional, camp-based responses to mass displacement. Operating in cities is challenging, as refugees are intermingled with other urban residents and the activities of humanitarian agencies must be supportive of—rather than separate from—those of national authorities.

As a result of this, humanitarians have had to review and adapt their response mechanisms. In the case of UNHCR, the Iraqi refugee operation triggered a number of innovative changes in the way the agency assists urban refugees. More efficient registration and reception systems helped reduce waiting times; community outreach mechanisms became more proactive, for example through the use of SMS messages; and cash assistance using ATM cards replaced earlier in-kind schemes. Many of these new approaches are now being employed to address the needs of Syrian refugees, especially in Jordan and Lebanon where the overwhelming majority of the refugees is once again being accommodated in urban areas.

Although there has been some improvement in the security situation inside Iraq over the past years, the country remains deeply fractured and struggles to gain stability. Returns have been taking place—UNHCR has recorded some 215,000 returned refugees since 2009—but over one million Iraqis remain internally displaced. UNHCR has been running a large resettlement operation from the Middle East to help Iraqi refugees restart their lives in third countries, with more than 80,000 having been accepted by countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia since the operation began in 2007. However, this solution is only open to a small fraction of the refugee population due to a limited number of places in receiving countries. There are no real prospects of local integration for Iraqi refugees within the region, leaving thousands who may never be able to return facing an uncertain future.

The Case of Yemen

Despite the fact that it is the poorest country in the Middle East, and deeply riddled with instability itself, Yemen has for many years had the region’s most generous refugee policy and provides prima facie refugee status to all Somalis arriving on its territory. The country currently hosts some 230,000 refugees, almost all of them Somalis, and almost all of them facing a bleak prospect of achieving any durable solutions in the near future. In addition, more than 100,000 people arrive every year on Yemen’s shores from the Horn of Africa, having crossed the Gulf of Aden in crowded and often unseaworthy boats, with the hope of finding safety in Yemen or economic opportunity in countries further to the north.

The means they use to travel, often through human smuggling rings, are highly dangerous, and hundreds have died during the perilous journey. Many others are beaten and abused by smugglers during the trip and arrive traumatized and ill on the Yemeni coast. UNHCR supports several NGOs who run reception centers along the 2,000-kilometer coastline, rescuing people from the sea and providing emergency care—or burial assistance—after passengers are pushed off boats by smugglers eager to return to international waters. This mixed flow of refugee, asylum-seeker, and migrant arrivals is an added challenge for Yemen, compounding its own fragile economy, very limited public health and education services, and highly volatile security environment.

Nearly 400,000 Yemenis themselves remain internally displaced as a result of fighting between government forces and Houthi rebels in the North, and a separate conflict in the southern Abyan governorate which started in May 2011. Some 100,000 have returned to Abyan since mid-2012, with UNHCR providing transport, basic relief, and shelter items as well as legal assistance. However, the displacement situation in the North remains unresolved. This year sees the country entering a crucial transition phase, with the government expected to introduce reforms that will facilitate more inclusive political processes and help stabilize the country. The future of Yemen’s displaced populations will depend on the government’s ability to ensure lasting success for this process.

With its own transition in a critical phase, and the added pressure of displacement challenges, Yemen needs strong support from regional and global actors to allow the country to move forward toward increased stability. Media attention is focused elsewhere, and support for economic development is scarce as long as the country continues to be as fragile as it is. This is a dangerous cycle that must be broken in order to ensure Yemen can overcome its internal crisis—and enable it to maintain the enormous contribution to regional stability it has been making, quietly, for many years by taking in so many refugees.

Libya, Two Years Later

The Libyan displacement crisis has long disappeared from the media spotlight, although not all of its components have yet been resolved. The Libya case was one of the largest mixed migration crises in the history of the region. More than 800,000 people crossed Libya’s borders, mainly to Tunisia and Egypt, in the space of a few months in early 2011. At the height of the conflict, daily arrival rates peaked at around 14,000 at the Tunisian border. Those fleeing included migrant workers, refugees from other countries, and Libyans themselves—all in all, more than 120 nationalities were represented. This tremendous diversity of national origin, profile, and protection needs made the Libya operation extremely challenging.

The substantial population outflows from Libya occurred at a time when the two main receiving countries—Tunisia and Egypt—were themselves experiencing fundamental political change and fragility. Nonetheless, both of these countries kept their borders open to the massive number of arrivals, and thousands found shelter with local communities. Together with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), UNHCR started a humanitarian evacuation by air and sea that eventually helped some 300,000 people to return to their home countries. Those who remained were mainly refugees and asylum-seekers from other countries who had been living in Libya, and who now had nowhere to go. UNHCR appealed to the international community for additional resettlement spaces for this group, to help them find a durable solution to their situation while at the same time easing the pressure on host countries. Some 3,700 have been accepted for resettlement, but several hundred still remain with no prospect for durable solutions.

Libya’s delicate post-conflict transition now offers both opportunities and challenges. Confrontations between armed militias, increasing instability in the east of the country, and the escalation of inter-ethnic and tribal conflicts pose significant challenges for the new government. In addition, of the more than half a million Libyans who were estimated to be internally displaced during the most intense period of fighting, nearly 60,000 remain displaced or have been uprooted again by fresh fighting. Many of the displaced belong to minority groups who are either unable or unwilling to return—thousands remain barred from going back by militias who control many of Libya’s rural areas.

The country’s location on one of the major mixed-migration routes towards Europe poses another serious challenge. Refugees and asylum-seekers from countries such as Somalia, Sudan, or Eritrea, are often comprised in these mixed movements. Travelling by the same means as economic migrants—often using smugglers—they risk being treated as illegal migrants without regard to their specific need for protection as people fleeing violence and persecution. Like most countries in the Middle East, Libya has no functioning national asylum system, and much of UNHCR’s work in the country is focused on helping the new Libyan authorities develop protection-sensitive migration policies. This is just one among many challenges facing the country in the tough period ahead, and while Libya may not need the same economic support as many of its neighbors, international political support for its efforts to build a modern and democratic institutional system are vital.

The Palestinian Tragedy

One must not forget that by far the largest and most protracted of all refugee problems today, not only in the Middle East region but in the world, is that of the Palestinian refugees, whose ordeal dates back nearly 65 years. Today, more than five million Palestinian refugees are dispersed across the Middle East, with hundreds of thousands more scattered throughout the world. The vast majority of them—those residing in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, as well as the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—fall under the mandate of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNWRA). With a broad humanitarian mandate focusing mainly on education, health, social services, and microfinance, the overwhelming majority of UNRWA’s more than 30,000 employees are refugees themselves. UNRWA has been faced with serious funding shortages in recent years, rendering one of the world’s most vulnerable refugee populations even more at risk. While the humanitarian aid and assistance UNRWA provides to the Palestinians can never be enough, it will be required as long as the issues of statelessness, prolonged military occupation, economic marginalization, and vulnerability characteristic of the Palestinian refugee crisis are not addressed.

The Palestinians’ continued refugee status leaves them fundamentally at risk, and each of the crises afflicting their host countries in recent years has further aggravated the difficult situation of Palestinian refugees in the region. After the fall of Saddam Hussein, many Palestinians in Iraq were subjected to harassment, torture, and targeted attacks. Thousands who tried to escape were trapped, many of them in the no-man’s land near the borders with Syria and Jordan where they lived for years in extremely harsh desert conditions. UNHCR tried to identify alternative solutions to bring them to safety, and some 3,000 particularly vulnerable persons were eventually resettled to more than a dozen different countries. However, the situation of many of Iraq’s Palestinians continues to be fragile.

In Syria, the more than half a million Palestinians registered with UNRWA had been well integrated into society; they were allowed to work and were given access to social services. The Syrian internal conflict has given a new dimension to their plight, with nearly 80 percent of refugees registered with UNRWA in Syria now requiring special assistance due to the conflict, and thousands having been further displaced by the violence. Some 30,000 have fled to Lebanon, where they have found shelter in existing and overcrowded camps, often in very difficult conditions. Humanitarians continue to appeal to all parties involved in the conflict to respect and protect the Palestinians, but these calls far too often go unheeded and they find themselves trapped again and again in violent incidents, such as the attacks on Yarmouk Camp outside Damascus. The international community needs to provide stronger support to UNRWA’s efforts inside Syria and to help prevent another massive displacement of Palestinian refugees which would have devastating consequences on regional stability and efforts to preserve asylum space.

Helping the Hosts

The story of refugees cannot be told without also telling the story of those who shelter them, often at enormous cost to themselves. The Middle East is home to both the world’s oldest and its most recent refugee crisis, and although few states in the region have signed the 1951 Refugee Convention, providing shelter and protection to those seeking safety at their borders is a deeply engrained commitment in most Middle Eastern countries. In fact, Islam’s 1,400-year-old tradition of generosity toward people fleeing persecution has had more influence on modern-day international refugee law than any other historical source.

As a study published in 2009 by UNHCR in cooperation with Naif Arab University and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation sets out, hospitality towards the needy stranger is deeply rooted in one of the key tenets of Islam. The Holy Qur’an calls for the protection of the asylum-seeker (al-mustamin), whose safety is irrevocably guaranteed under the institution of aman. This generous treatment is the same for Muslims and non-Muslims, as set out in the Surat Al-Tawbah: “And if anyone of the disbelievers seeks your protection then grant him protection so that he may hear the word of Allah, and then escort him to where he will be secure. That is because they are a people who do not know.” (Surah 9:6) One measure of a community’s moral duty and ethical behavior is how it responds to calls for asylum. The extradition of al-mustamin is explicitly prohibited. This same principle, known as non-refoulement, is one of the cornerstones of modern refugee law, banning the forceful return of refugees to a place where their lives and freedom may be in danger.

But the traditional generosity of Middle Eastern countries towards refugees from the region comes at a high cost. The capacities of host countries today are dangerously overstretched. The acute pressure on water resources in Jordan is but one example. In Lebanon, the influx of Syrian refugees has increased the population of this tiny country by nearly 10 percent. At a time when nearly all of the countries hosting large numbers of refugees in the region are themselves subject to varying degrees of political instability, social tensions, economic challenges, and security concerns, they need all the support they can get to help maintain the delicate balance of attending to their own societies’ needs while sheltering hundreds of thousands of refugees.

International donor support to refugees in the Middle East has been stronger than in many other regions of the world, but direct support to the victims is not enough. The world’s solidarity must translate into real burden-sharing and responsibility-sharing, supporting governments and communities in refugee-hosting countries. Countries that have borne the brunt of the refugee crisis must be given the means to manage this additional pressure. This is true both in the emergency response phase and during the collective pursuit of durable solutions which—as many of the situations described above illustrate only all too well—can take years. Solidarity can take many forms: during exile, it means providing development assistance to refugee-hosting areas, or making additional resettlement opportunities for refugees available. Once conditions are ready for voluntary return, solidarity programs must focus on the provision of essential services and job opportunities in the countries of origin to ensure reintegration is sustainable.

In this context, the donor support which countries from the region are providing through their own channels to refugees and their hosts, both in the Middle East and beyond, is encouraging. Take the example of Syria: a month after the United Nations launched one of the biggest humanitarian aid appeals in its history, asking for $1.5 billion over six months to assist those affected by the conflict in Syria as well as refugees in the surrounding countries, an international donor conference hosted by Emir Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jabir Al-Sabah of Kuwait in January brought in promises of $1.5 billion to support humanitarian assistance. Some two-thirds of the forthcoming funds were announced by Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. While these pledges are yet to be realized, the amount indicates strong international financial support for the people of Syria.

Gulf donors are also becoming increasingly active in international humanitarian fora, with the UAE quickly evolving into the industry’s most important emergency logistics hub. In addition, governments and charities are contributing actively to current humanitarian debates and to innovation, via initiatives such as the Dubai International Humanitarian Aid and Development. As they further expand their role as international donors, the Gulf countries’ efforts could stand to gain in traction and effectiveness if they were better integrated with multilateral frameworks in the future. Better coordination on the ground would help improve the efficiency, flexibility, and sustainability that are needed when trying to stretch generous but on the whole insufficient funding to meet ever-growing humanitarian needs.

Beyond Humanitarianism

The Middle East today is not the world’s only trouble spot, but it is by far its most visible one. While this visibility may to some extent facilitate the humanitarian response to its crises—thanks to the additional funding and space for advocacy that often accompanies media attention—it has done nothing so far to help bring about actual solutions to the region’s current conflicts. These solutions cannot be humanitarian. They will not be military. They must be political.

The world we live in has become more dangerous than it was two decades ago. Unpredictability has become the name of the game. Crises are multiplying. Conflicts are becoming more complex and intractable, and are exacerbated by rapid demographic change, urbanization, and dwindling natural resources including food, water, and energy. At the same time, the world lacks the governance capacity to deal with these challenges. There is no effective multilateral approach to any of them.

Large refugee populations are the visible result of many of these crises, but they often stay on long after the conflict in question has ceased to be in the spotlight of media attention. In the Middle East, this is the case for almost all of the large displacement situations, which keep millions of people languishing in exile and with uncertain prospects for the future. At the moment, all eyes are focused on the plight of Syria, its people, and its refugees. Given the current gloomy outlook for Syria’s future, there is a real risk that this newest refugee crisis could be added to the list of protracted situations of exile that plague the region. The international community must do whatever it can on the political level to prevent this from happening.

The Middle East’s refugee crises are symptomatic of many of the region’s political and security challenges. Large-scale displacement is also a source of concern for the stability of the region in general, and receiving countries need robust international support to help stabilize their economies and enable governments to maintain their generous open-border policies that are at the basis of refugee protection. In a region that has become the world’s biggest producer of forced displacement and where peace and stability remain elusive for many, much will have to change in the coming years to help governments and communities cope with these challenges. Politically inclusive arrangements are needed, which extend to displaced populations, to bring sustainable solutions to those who have been uprooted from their homes. For this to happen, the many emerging civil society actors in countries across the region have an important part to play, and should be strongly supported. The international community must go beyond offering humanitarian assistance to the human fallout of war, it must provide real political and economic support throughout the long and extremely difficult transition period that lies ahead.

António Guterres has served as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees since 2005. He oversees 7,685 staff members working in 126 countries, and an annual budget of $3.6 billion. He was prime minister of Portugal from 1995 to 2002, during which time he was heavily involved in the international effort to resolve the crisis in East Timor. As president of the European Council in early 2000, he led the adoption of the Lisbon Agenda and co-chaired the first European Union-Africa summit.