India’s Dream Jobs

Narendra Modi is prime minister of India because voters believed he could boost growth and deliver jobs. So far, he has succeeded in the first goal but failed dramatically in the second.

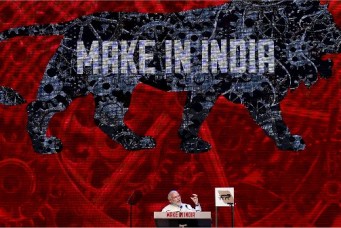

Prime Minister Narendra Modi at inauguration of the ‘Make In India’ week in Mumbai, India, Feb. 13, 2016. Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

A million Indians join their labor market each month, and India’s leaders are desperate to find them work. When Narendra Modi was running for office in 2014, he promised that if elected he would create 10 million new jobs a year. Today, Prime Minister Modi is hoping that Indians overlook a couple zeros; in 2015, the economy added just 135,000 jobs.

This failure is not from lack of effort. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has pushed bold legislation through parliament designed to grow the economy, including easing restrictions on foreign investment and simplifying the country’s sales tax regime. Their reforms have helped make India the fastest-growing large economy in the world. While some Indians are reaping enormous profit from this growth, the rising number of India’s jobless—the highest proportion in five years—sees little benefit.

To explain the paradox in India, Modi’s critics have focused on policy issues: the bloated public sector, or the BJP’s failure to relax the country’s rigid labor market or loosen restrictions on acquiring land for investment. However, a changing global economy may deserve more than Modi’s share of the blame. To absorb the huge number of workers joining the economy each year, a group the size of Belgium’s population, India must modernize at the rate and scale of China. China and the East Asian Tigers leveraged globalization two generations ago to grow their economies at remarkable rates. Unfortunately, Chinese-style factory-driven industrialization is no longer possible.

The eighteenth-century British economist David Ricardo anticipated India’s quandary when he hinted at the underbelly of his theory of comparative advantage, which shows that all countries benefit from each specializing in producing and trading goods according to what they do best. Ricardo’s examples of British textiles and Portuguese wine pointed toward a crucial qualification: countries can get stuck at certain levels of the value chain. America gets to make satellites while Bangladesh makes t-shirts. Bangladeshis make t-shirts while a few, highly skilled Indians make generic pharmaceuticals. The end product of increased trade is greater growth, to Ricardo’s credit (Americans, Bangladeshis, and Indians all get to consume more, in the aggregate). But the end product is not necessarily jobs and the equitable distribution of wealth. Globalization can condemn India to specialize in goods and services that do not need significant labor inputs.

Automation is the other fruit that fell from the forbidden tree. Before India began liberalizing its economy following a balance of payments crisis in the early 1990s, it was nearly an autarky. By shutting out foreign competitors, Indian leaders had hoped to incubate industry at home (an understandable belief given that it was a foreign company that had colonized India). That plan never worked, but Modi is trying to revive a similar focus on domestic production with his “Make in India” campaign. This time, he is hoping that foreigners will invest in India to replicate Mexico’s maquiladoras or China’s success in Shenzhen.

Yet when global corporations do arrive in India, they bring money and technology—but few jobs. Rising labor costs and low fuel prices are pushing firms to automate their production. Last year, Ford invested a billion dollars in Gujarat, Modi’s home province, to build one of the most highly automated plants in Asia. That plant will employ 2,500 lucky people. Fewer and fewer industries require the vast numbers of unskilled workers India can offer. And those that do often choose to set up shop in Bangladesh, which has cheaper labor and fewer regulations—and created twice as many jobs as India did in 2015.

Despite these challenges, if India still wants to develop rapidly à la East Asia, it will find that path increasingly illegal. When industrializing, East Asian nations at once opened their economies to global trade and instituted aggressive industrial policies to support target industries. However, deploying many such strategies today would trigger sanctions from the World Trade Organization (WTO). For example, when India tried to foster its nascent solar-panel industry through minimum domestic sourcing requirements, the United States complained to the WTO that these policies were unfair trade practices. India lost that case and its appeal last year.

Technology and the global economy have pushed some poor nations to deindustrialize at far lower levels of average income than in the past. The well-worn path of development is suddenly inaccessible. Scholars Amrit Amirapu and Arvind Subramanian have demonstrated that deindustrialization is already happening in parts of India. Industrial manufacturing is not the only path to development, and India’s success in the information technology sector is a significant driver for its economic growth. But the dismal state of the country’s education infrastructure does not encourage hope that the services sector will be able to provide anywhere near the number of jobs the country needs.

Indians handed Modi’s BJP the largest mandate in decades for its Hindu nationalism, relatively corruption-free reputation, and a “kick-the-bums-out” reaction to the Indian National Congress. However, Narendra Modi is prime minister because voters believed he could boost growth and deliver jobs, and he will be judged accordingly. So far, he has succeeded in the first goal but failed dramatically in the second.

His critics on the right decry Modi for not going far enough to implement the textbook plan for liberalizing India’s economy. Part of Modi’s inability to do so is due to the staunch opposition he faces in parliament, especially from the upper house, which he does not control. But the other cause is likely his own doubt that such prescriptions would work in India. The textbooks describing how a developing economy is supposed to modernize were made in another era, by Westerners writing in a wealthy corner of the globe. Few speak to an age of jobless growth in the developing world. If Modi fails to make good on his jobs promise, he may soon be forced to join the ranks of Indians looking for work.

Faisal Hamid is a reporter-researcher at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs.