Saving Yemen

A victory in the civil war, by either side, is unlikely to bring peace.

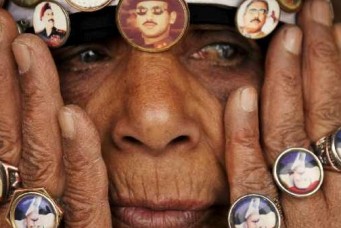

A school damaged by Saudi Arabian-led air strikes last year, Sanaa, Oct. 5, 2016. Khaled Abdullah/Reuters

As the conflict in Yemen draws to the end of its second year, the human toll of the political tragedy continues to mount. Rough estimates of civilian casualties, since fighting began in March 2015, may now exceed 10,000 killed with over 40,000 injured. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has reported that over three million of Yemen’s 27.5 million citizens have been internally displaced by the conflict, while over half the population is considered food insecure. Famine and epidemics of disease may be on the near horizon. Five years after Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s election as interim president started the clock on the only negotiated political transition of the Arab Spring, the future survival of Yemen hangs in the balance.

Regrettably, the optimism last year that the parties were moving closer to agreement on the outlines of a political deal has faded despite a months-long, United Nations-led negotiation in Kuwait, followed by desperate attempts by the international community to broker a ceasefire later in the year. Yet the fighting remains stalemated. The government, supported by the Saudi Arabian-led military coalition, is strengthening its hold on the southern part of the country, while Houthi forces, aligned with former President Ali Abdallah Saleh, are firmly in control of the north, including the capital, Sanaa, and reaching to the border of Saudi Arabia.

Recent progress by the government in seizing control of the Red Sea coastal region, the Tihama, perhaps soon to include an assault on the key port of Hodeidah, will undoubtedly be a blow to the Houthis. But it is unlikely to bring a dramatic change to the course of the conflict. In fact, one potential outcome of the current situation is the de facto re-division of Yemen along the north-south border that existed until unification in 1990. While there are some who might welcome that prospect, it is fundamentally an outcome to be avoided, as it will mean two failed states in the southern Arabian Peninsula, each one incapable of providing adequately for its population and both becoming breeding grounds for violent extremist groups.

But even should the prospect of a negotiation between the two main parties to the conflict improve, that success will not bring a short-term resolution to the fighting and instability. In the long negotiations in 2011 between former President Saleh and his political opponents, Yemen’s preeminent statesman and patriot, the late Abdul Karim Al-Eryani, a former prime minister, warned the parties continuously that an armed conflict in Yemen, once started, would not be easily stopped. His argument was that conflict would bring a resurgence of a tribal culture that prioritized clan honor, vengeance, and revenge over security and stability. That, indeed, appears to be happening as conflicts around the country, including around the besieged city of Taiz, increasingly take on the coloration of tribal vendettas and the resurrection of ancient rivalries rather than organized conflict between identifiable parties. Thus, even in the event that the parties agree on a political framework for governance in Sanaa, their capacity to bring a halt to the fighting in the countryside is going to be extremely limited.

Moreover, the two Yemeni coalitions that are parties to the conflict are, themselves, internally fragile. The Houthi-Saleh alliance, in particular, is a marriage of convenience rather than a true partnership and is unlikely to survive in a political environment rather than an armed conflict. Long years of enmity between Saleh and his followers and the Houthis have been papered over, not resolved. And both sides have political aspirations that will be difficult to accommodate when it comes to a real political process. It has long been anticipated that the final act of the drama over political control in Sanaa will be a showdown between Saleh and the Houthis, and signs of tension between the two sides abound, including Houthi negotiations at the end of the year over a ceasefire agreement that did not include Saleh’s representatives.

Despite the challenges, the international community has few options except to maintain its support for the political negotiations being managed by UN Special Envoy Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed. There will not be a military conclusion to the Yemen conflict. Only a political arrangement, within the framework of UNSCR 2216 but offering sufficient flexibility to draw in the Houthis, can bring an end to the fighting and allow for the re-establishment of some degree of governance in Sanaa. Under that circumstance, priority should be placed on completing the remaining steps of the Yemeni transition plan and enabling the establishment of a new, credible government that can begin the process of restoring security and stability, repairing damaged infrastructure, and restarting economic activity.

The other immediate priority must be the delivery of desperately needed humanitarian supplies. According to the UN, more than seven million Yemenis are on the brink of famine, with already some half million children facing “severe acute malnutrition.” Given the unsettled nature of much of the countryside, internal distribution of supplies will remain a challenge over the long-term. Nevertheless, should the government forces and its coalition backers succeed in securing the port of Hodeidah and the road from Hodeidah to Sanaa, there should be a clear understanding that repairing damaged port facilities will be completed on an urgent basis and that the Saudi Arabian-led coalition will guarantee unfettered access to the port for international humanitarian relief organizations.

Even with success in these immediate tasks, Yemen’s recovery will be long and the ultimate outcome not assured. But without these steps, Yemen’s continued descent into complete social, political, and economic collapse is all but guaranteed.

Gerald M. Feierstein served as United States ambassador to Yemen from 2010 to 2013. He is the director of the Center for Gulf Affairs at the Middle East Institute.