Mashhad’s Rebuke to Rouhani

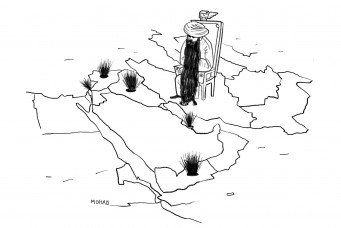

Entrenched interests based beyond Tehran stand to gain politically from the Iran protests of late December and early January, leaving President Rouhani’s administration at a crossroads.

It is significant that the recent protests began in Mashhad, a city far from Tehran and home to the mausoleum of Ali al-Ridha, the eighth Shia Imam, which attracts millions of pilgrims each year. Astan-e Quds Razavi, the charitable foundation that controls the shrine, is incredibly wealthy; it controls over half of the land in town, and over the years has morphed into a powerful conglomerate that employs thousands of people.

Mashhad is also home to Ahmad Alamolhoda, a hardline cleric hand-picked by the Supreme Leader to preside over the Friday prayers in the city. When the longstanding custodian of al-Ridha’s shrine passed away in March 2016, the conservative camp—still soul searching with only one year until Hassan Rouhani’s expected bid for reelection—saw an opportunity to appoint as its head Ebrahim Raisi, a conservative cleric largely unknown to the public, and who just so happens to be Alamolhoda’s son-in-law. Showered with coverage from conservative outlets, he suddenly shot to fame. Just over a year later, having coopted fellow Mashhad-born Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, the longtime mayor of Tehran, Raisi presented a serious challenge to Hassan Rouhani. Though he lost the election, Raisi did get close to sixteen million votes, a real feat considering the deep divisions among the conservatives.

Entering his second term, Rouhani had no intentions of giving his rivals a free pass. When he addressed parliament about next year’s budget bill on December 10, he pulled no punches. He spoke openly of unaccountable centers of power in an animated tone, attacking their grip on everything from real estate to the foreign currency market. This seems to have been the straw that broke the (conservative) camel’s back.

With U.S. President Donald Trump decertifying the nuclear deal in October and threatening to refuse to issue sanctions waivers, the duo from Mashhad and some of their conservative allies are said to have smelled an opportunity. Although there is no concrete evidence, in Tehran, everyone seems to “know” that Alamolhoda, his son-in-law and some of their associates plotted to undermine and embarrass Rouhani by instigating protests planned to build up to Dey 9 (December 30), the official anniversary of the “defeat” of the 2009 Green Movement.

The initial protests in Mashhad on December 28 metamorphosed into nationwide unrest. Over a thousand protesters were reported to have been detained; almost two dozen died. Yet it was only a matter of time before the seemingly leaderless protests were stamped out.

In their wake, many questions remain. But one thing is clear: Rouhani is at a crossroads. His administration has exerted great pressure to minimize violence, partly in order to deflect the foreign pressure his domestic foes seem to crave. What now lies before him is a unique opportunity to turn the tables on his opponents: to leverage an embarrassment into a tool for more concessions from the Supreme Leader, such as a greater mandate to tackle unaccountable institutions. If he fails, he may not only lose the chance to undermine these unaccountable powers, who generate grievances but assume none of the responsibility, but also any political standing he has gained from attacking them.

This article is reprinted with permission of Sada. It can be accessed online here.

Mohammad Ali Shabani, a PhD candidate at SOAS, University of London and Iran Pulse editor at Al-Monitor. On Twitter @mashabani.