Patrons of Peace and Conflict

In Northeast Africa today, Middle Eastern states vie for influence, and African governments accede—with conditions

Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir welcomes Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at Khartoum Airport, Sudan Dec. 24, 2017. Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah /Reuters

Suakin sits along Sudan’s Red Sea coast, a small grouping of faded buildings and historical ruins containing a proud fishing community. The town is a coastal village and the main attraction is the ancient ruins—some dating back to the fifteenth century—as well as the outer shell of a British fort that persists as a symbol of Sudan’s colonial past. In its prime, Suakin was a key transit point for African Muslims on the pilgrimage to Mecca, but with the advent of air travel the town has fallen from prominence, an abandonment only made worse by the collapse of Sudan’s tourist industry.

Yet in January 2018, Suakin was at the center of a rapid deterioration of diplomatic relations between Sudan and its northern neighbor Egypt, triggering talk of possible war between the two nations. In December 2017 Turkish President Recep Erdoğan visited Suakin ostensibly to inspect the large-scale restoration of the historical town financed by the Turkish government. Then a few weeks later, in January 2018, Erdoğan returned to Sudan to sign among many other agreements, a deal to hand over Suakin to Turkey altogether—just for tourism, both governments maintain—which Sudan’s neighbors have interpreted as an act of aggression.

The situation in Suakin is emblematic of increasingly complicated geopolitical relations in Africa’s northeast corner. From Egypt to Tanzania, decades of political ambivalence around unsettled borders, access to the sea, and ambiguous agreements about the waters of the Nile are flaring up. Much of this tension is left over from Britain’s colonial history in the region, but some is entirely new, aggravated by simmering conflicts in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region. There are also centuries of connection between the various states as well as internal realignments that complicate the situation further.

Since 2017, the nations of the GCC and their allies have been embroiled in a diplomatic crisis whose impact is being felt far beyond the region. In Northeast Africa, including Egypt, shifting allegiances in the Middle East have triggered unprecedented geopolitical transformations—with both conflict and peace emerging in unexpected places. The conflict over Suakin shows how connections with the Gulf crisis have exacerbated tensions in Northeast Africa, while the unexpected peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia stands as a rare example of a positive outcome of the GCC crisis. Both these situations underscore the strong economic and political connections between the regions, and the significant influence that wealthy Gulf states wield in the area. Yet, African countries are not simply following the will of their wealthy benefactors—there have also been notable demonstrations of independence and agency in containing the impact of the crisis. Whether or not these demonstrations of agency will triumph over the deepening tension in the Gulf and the growing economic crisis in Northeast Africa remains to be seen.

The year 2018, with its seismic shifts and unprecedented developments, is an excellent moment to examine a handful of the connections between the Gulf and Northeast Africa. Beneath geographical boundaries, there are layers of live wires connecting these regions, many of which are about water.

A Game of Tit for Tat: Halayeb and Suakin

By 2018, every country in continental Africa’s northeast—defined here as the countries with capitals east of 20 degrees longitude, and north of the Equator— had a disputed border. Since independence, Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Kenya, Uganda, and Somalia have all fought border wars of varying intensity, many of which were not resolved but simply allowed to cool as other geostrategic priorities superseded them. Today, these border disputes present easy focal points or excuses for other faces of conflict. For example, current tension between Egypt and Sudan over Suakin is just the latest phase of a convoluted relationship that has often centered on their shared border, and specifically, the Halayeb Triangle.

Indeed, the Halayeb Triangle is a 20,000 square foot region that has been the subject of a border dispute between Cairo and Khartoum since Sudan gained independence from Britain in 1956. Unlike Suakin—where the geostrategic influence far outweighs any immediate commercial value—the Halayeb Triangle is a resource-rich territory and both countries have attempted to offer international companies the rights to explore the area for oil and minerals.

By the 2000s the Halayeb conflict had cooled, particularly when former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi appeared open to renegotiating the status of the territory. But in 2016, Egypt and Saudi Arabia entered an agreement that seemed to reignite the unresolved row, Egypt apparently ceding two islands in the Red Sea to Saudi Arabia, much to the ire of Sudan. According to Sudanese officials, the fine print of the deal also claimed that Sudan had ceded Halayeb to Egypt. Meanwhile, Sudan was not a party to the agreement, and in December 2017, President Omar Al-Bashir wrote to the United Nations to condemn the Saudi–Egyptian deal while recalling the Sudanese ambassador to Cairo in January 2018.

Arguably, Sudan’s 2017 agreement with Turkey was a response to Egypt’s 2016 commitment to the Saudi–Egyptian deal. Cairo has interpreted the possibility of a permanent Turkish presence at its doorstep as a subtle act of aggression given that Erdoğan continues to provide sanctuary to members of the Muslim Brotherhood fleeing the Abdel Fattah El-Sisi regime. Erdoğan has also been openly supportive of jailed former Egyptian president Morsi and with Turkey’s influence growing on the East African coast stretching down to Somalia, the possible ceding of Suakin is a major concern for Egypt.

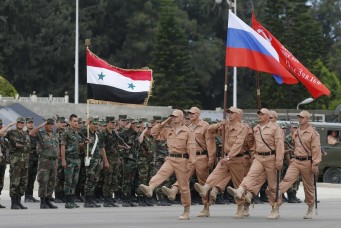

Choosing Sides in the GCC Crisis

The struggle over Suakin is also the latest phase of a spillover of GCC tensions onto the East African coast, as countries like Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and lately Sudan have experienced pressure to take sides in the standoff between Qatar on one side and Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on the other. This crisis also implicates Iran and Saudi Arabia, and is complicated by the ongoing wars in Syria and Yemen. Turkey has allied itself with Qatar and Iran, while Saudi Arabia counts Egypt among its allies, and both axes have invested greatly in courting African allies like Sudan and Ethiopia.

Part of the reason why the GCC is able to exert such influence in Northeast Africa—including Egypt—is that most of the countries in the region are broke after nearly a decade of illusory growth and borrowing for large-scale infrastructure projects. Qatari and Saudi Arabian corporations have purchased large tracts of arable land in Sudan for agriculture, a key source of revenue for the financially and increasingly politically hamstrung Al-Bashir regime. Environmental activists within Sudan have criticized this relationship, particularly as much of the land that has been acquired is in the fertile Nile Basin, which accounts for a significant amount of Sudan’s agricultural output. While Qatar is not the only GCC country with significant land purchases in Sudan, it is certainly one of the most influential as in 2009 the Sudanese government signed a $1 billion deal allowing a Qatari corporation to develop up to 20,000 hectares of arable land.

Egypt also faces major economic challenges and has cast its lot with Saudi Arabia, including the aforementioned cessation of territory, despite a complicated diplomatic history. In June 2018, President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi reaffirmed that Egypt’s relationship with Saudi Arabia was one of its key strategic partnerships. And in 2017, Egypt was one of the first countries to cut ties with Qatar at the behest of Saudi Arabia, subsequently entering numerous bilateral agreements with Riyadh, notably the Red Sea islands deal offering the promise of increased economic support for Egypt.

Taken together, these events largely explain why the crisis around a small, nearly derelict fishing village threatens to escalate into a significant issue. Suakin is symbolic of shifting allegiances between African countries that have never fully resolved their diplomatic relations, as well as the increasing ability of Middle Eastern states to use money to influence domestic policy within those countries, often to an absurd degree. Certainly, the wilful cessation of territory to both Turkey and Saudi Arabia was unprecedented in African diplomatic history, where autonomous control of land by indigenous people was the crux of independence movements across the continent. From outside the countries involved, the actions of Sudan and Egypt seem like a significant backward step in the long-running struggle for independence.

Yet, the unrest in Africa’s northeast is not just about outside interests. In fact, what presents as opportunistic alignment with GCC countries are arguably defensive measures in the context of heightened regional tensions—primarily over water.

Climate scientists have long warned that scarcity of water may trigger the next world war, and the increasingly fraught relationships in Africa’s northeast suggest that this prediction is a little too close for comfort. Egypt, Sudan, and other countries along the River Nile have had clashes in the past regarding the use of the river—indeed it was the motivation for much of Britain’s colonial enterprise in the region. But access to fishing and trade routes in the Red Sea has also been a point of contention, and when layered with the GCC crisis, what we are witnessing is the escalation of unresolved sore spots between nations. Where tension over water has been almost a constant, foreign interests and funding have arrived to complicate the picture.

Securing Water in the Sahara

The most significant face of this is the escalating stress around the use of Nile waters. The two main tributaries of the world’s longest river rise in South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Uganda (and by extension Kenya and Tanzania) before meeting in Khartoum and flowing through Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea. While the longest section of the river is in Egypt, the southern countries dispute Cairo’s claims to rights of use, many of which were established by colonial-era agreements to serve British occupation. Egypt relies completely on the river for its freshwater but countries upstream are increasingly damming the tributaries that feed into the Nile for their electricity.

Specifically, Egypt has taken issue with Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Located in northwest Ethiopia, close to its border with Sudan, the GERD dams the Blue Nile tributary, which contributes up to 86 percent of the total volume of the Nile during the rainy season. When completed, the GERD will be the single largest infrastructure project in Africa and the largest dam on the continent with a volume of over 10 million cubic meters and a maximum capacity of 6.45 gigawatts.

The GERD is one of many dam projects that the Ethiopian government has undertaken over the last ten years as part of a broader investment in the country’s infrastructure—and part of the reason why the country is running out of money. After decades of conflict, Africa’s second most populous country settled into a pattern of state violence and repression that stagnated the economy. While socialism remains the official economic approach, since the turn of the millennium state policy changed to embrace selective capitalism— similar to China. The vast infrastructure developments are meant to stimulate economic growth and create opportunities for the country’s mostly rural and poor population.

Ethiopia’s dams present environmental and political challenges for its neighbors. Logically therefore, Sudan should be at the forefront of challenging Ethiopia’s dam building, and initially the Khartoum government did oppose the GERD. But recently the Al-Bashir regime has been enthusiastic about the project in part because of agreements with Ethiopia to purchase surplus electricity generated by the projects. At current rates of population and economic growth, Ethiopia is unable to absorb the excess energy generated by the projects while both Kenya and Sudan suffer from relatively high energy prices. This is a strategic long-term gamble by the Ethiopian administration to secure its energy future at significant political cost in the short term.

Tension over the GERD in part explains why Sudan and Egypt are currently at odds, but Sudan and Ethiopia are not natural allies either, forced by domestic and regional developments into an expedient if uncomfortable relationship. For both countries, the compromise is necessary. Both are in the throes of significant economic crises, which have triggered seismic political upheavals that both governments are struggling to contain. For Ethiopia, an unlikely alliance with Sudan not only wills the GERD into existence, but also offers the promise of a new route to the sea. For Sudan, it brings in a much-needed source of energy as the oil wells of South Sudan remain choked by civil war and simmering tension between the two countries over the Abyei oilfields.

Ethiopia’s Quest for a Port

Access to the sea is another facet of the role of water in geopolitics in Northeast Africa. In 1994, Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia and since the 1998 war between the two, Ethiopia—the largest economy in the region—has been landlocked and reliant on Djibouti for access to the sea: up to 90 percent of Ethiopia’s imports enter the country through Djibouti’s ports. At the same time, as part of the GCC crisis, the UAE has been investing significantly in ports along the East African coast, notably in Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Somaliland. Of these countries, only Djibouti has openly taken sides in the GCC crisis, leaving Ethiopia vulnerable to the vacillations of a conflict which does not concern it.

Nonetheless, for cash-strapped countries like Ethiopia, the GCC crisis has presented an unexpected boon. The Gulf nations and their allies are scrambling to build new allegiances in the region in the most predictable way possible, by using the promise of aid and foreign direct investment. And traditional donor countries like the United States and the UK are increasingly facing inwards to their own domestic challenges, leaving a major geopolitical gap. This creates a new lever that is clearly being used to force realignments in the region and to create coalitions of unnatural bedfellows that can be relied upon for geostrategic support as the situation in the Gulf remains fraught.

In Ethiopia, while the details remain shrouded in diplomatic secrecy, the fact that the prime minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed and his Eritrean counterpart, Isaias Afwerki, signed the same peace agreement three times this past summer—in Asmara, Abu Dhabi, and finally in Riyadh—and not in traditional diplomatic centers like Geneva, New York, or even Nairobi, indicates that both the UAE and Saudi Arabia played significant roles in brokering an unexpected rapprochement between the two, effectively ending a twenty-year war.

The move has been hailed as the most significant diplomatic development in Africa, ending a seemingly senseless conflict and leading to a drawdown along Africa’s most militarized border. In August 2018 after the agreement was signed, men and women gathered at the border and openly wept in each other’s arms; family members that had not seen each other since the beginning of the war in 1998 were finally reunited. The causes of Ethiopia and Eritrea’s unexpected peace are complicated, but analysts suggest that it has everything to do with pressure coming from the UAE as part of a broader effort to increase its influence in the region.

The Ethiopia–Eritrea peace caught Horn of Africa analysts by surprise as both nations looked to have settled comfortably into the routines of a war that has fundamentally altered both societies, not just militarily. Other countries and institutions like the African Union and the United Nations had several times attempted to broker peace between the neighbors to no avail. It may not have been a single thing—it was more likely a confluence of circumstances that gave the UAE and Saudi Arabia the leverage they needed to push the neighbors together. The first and most obvious of these is money.

One of the worst-kept economic secrets in the region was that Ethiopia’s centralized economy had been struggling with diminishing foreign exchange reserves and was facing imminent collapse even while the state borrowed heavily—from China especially—to finance large-scale infrastructure projects. Officially Ethiopia’s economy has been growing at up to 11 percent per annum, but economic experts had long doubted the veracity of these statistics given that most ordinary Ethiopians remained visibly poor. Meanwhile, protests and violent reprisals triggered by state plans to expand Addis Ababa in 2016 snowballed into the threat of national disintegration.

Facing a compounding domestic crisis and in desperate need of foreign exchange to sustain the illusion of economic growth, Ethiopia’s government allegedly found little sympathy in traditional partners like the United States and China. Increasing political repression had recently dried the aid taps from the West, while the government was already too significantly indebted to Beijing. This, according to experts, is why following an abrupt change of prime minister, the Ethiopian government reached out to Saudi Arabia. For the Saudis, facing increasing criticism over the war in Yemen and domestic issues like the mass arrests of women’s rights activists in 2018, this would be a major diplomatic victory. But it would also bring Ethiopia, a powerful and influential African country, into their sphere of influence while securing their presence on the Red Sea—one of the world’s most lucrative sea routes.

From an Ethiopian standpoint, the risk of Djibouti becoming embroiled in the Gulf crisis would have been significant and alarming—a lesson the region learnt during Kenya’s 2007–2008 post-election crisis when imports to Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda were significantly disrupted by a crisis they could not control. A menu of options for access to the sea—again in the context of a general economic crisis—would have been well worth pursuing.

According to insiders, the Ethiopia–Eritrea peace deal came on the heels of a diplomatic summit between Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia in May 2018. At the summit, Ahmed promised to abide by the terms of the Algiers Agreement on peace between the two countries if Afwerki agreed to meet Ahmed and discuss other issues of import. Ahmed went as far as calling Afwerki at the summit, but the call was spurned perhaps out of a habit of frosty relations. Yet by July, Ahmed was in Asmara for a face-to-face meeting with Afwerki.

What has followed is a flurry of increasingly unbelievable diplomatic efforts aimed at normalizing relations between the two countries at hyper-speed. In June 2018, no Ethiopian official had set foot in Eritrea since 1998. By August, both countries had reopened diplomatic missions in each other’s capitals and reduced military presence along the border. By September of the same year, Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers were dancing alongside each other in celebration. Whereas in January 2018, Ethiopia relied on only one choice of port, in September 2018 it has four possible options. And in September 2018, Ahmed and Afwerki met in Riyadh to sign a peace agreement for the third time this year, cementing Saudi Arabia’s footprint on the process.

The Allure of Northeast Africa

There are of course more layers and intricacies to the geopolitics of Northeast Africa, but just by focusing on the issue of water—either access to the sea or to the Nile—we see how pathologies and conflict economies travel into and across the region. The four countries discussed here—Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea—are not the only ones affected by shifts in the Gulf but they have come closest to absorbing the entropy from that region into their domestic and regional politics.

These major developments in the relationship between Northeast Africa and the Middle East also obscure several less visible but equally significant developments. Notably, Turkey has made significant diplomatic inroads in Northeast Africa, particularly as a key international partner for Somalia as the war-torn nation seeks to rebuild. In 2011, President Erdoğan became the first non-African leader to visit Mogadishu since the onset of war in 1991. Subsequently, Turkey has funded numerous key reconstruction projects in Somalia, notably the main international airport—which doubles as the hub for international diplomacy in the context of Mogadishu’s insecurity—and training and reforming Somalia’s hitherto celebrated military.

Turkey is also implicated in the struggle to control the waters of the Red Sea. Since 2017, Turkey has maintained a military base in Somalia, giving it a major presence on the East African coastline. Meanwhile, Djibouti continues to host foreign military bases from more countries than any other on the continent. Militaries from the United States, France, Italy, China, and Japan all operate from the country. These countries continue to expand their military presence in the region through aggressive base and port building. Today, the United States has a seemingly permanent presence in Kenya and Uganda, while China has established a military presence in Sudan and South Sudan to protect its oil interests in the latter, as well as its first overseas military base in Djibouti. The militarization of Northeast Africa by foreign powers shows no signs of abating.

As it stands, most of the countries in Northeast Africa have opted to stay neutral in the GCC crisis, with the notable exception of Djibouti. But the pressure persists. Somalia has, for example, found itself sandwiched between the interests of key traditional partners. Experts at the Crisis Group argue that tensions in the Gulf have exacerbated hostilities between factions angling for control over the still-fragile government in Mogadishu, as well as between the various semi-autonomous and autonomous regions in the country. And as demonstrated above, they have made unlikely allies of countries like Sudan and Ethiopia, while exacerbating pre-existing regional disputes over land and water.

Wealth disparities have cast Gulf countries primarily in the role of donor nations and African countries in the role of aid recipients, giving the former significant sway over the domestic and regional politics of the latter as demonstrated by the recent experiences of Egypt, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, and others. At the same time, perhaps having witnessed the devastation geopolitical maneuvering in the Gulf has caused in Syria and Yemen, African countries like Ethiopia are increasingly unwilling to allow their survival to remain predicated on what happens in other parts of the world. There have been demonstrations of agency that may escalate in response to regional realities. For example, in the fact of its cash crisis, Sudan is taking an aggressive lead in supporting peace efforts in South Sudan, even when the Al-Bashir regime faces international sanction.

Overall, political changes in the Gulf present both opportunities and new constraints for African countries, including Egypt. A new source of aid and foreign direct investment also means a new patron to please, a new set of conditions to negotiate, a new series of hoops to jump through. Major outcomes of the past year have included the so far relatively peaceful transition in Ethiopia, and the unexpected peace in Eritrea. Money is entering economies like Egypt and Sudan after years of debilitating cash drought. However, Africa has long experience with the problems that conditional assistance can cause, and one has the sense that at some point the nations in the Gulf will call in these favors. The demonstrations of agency by African countries are encouraging, but it is unclear if they are braced for the coming impact.

Remember Suakin, once a point of engagement for African and Middle Eastern countries, now a symbol of the complex tensions that bind them.

Nanjala Nyabola is a writer and political analyst based in Nairobi, Kenya. She is the author of the forthcoming Digital Democracy, Analogue Politicsand a co-editor of Where Women Are: Gender and the 2017 Kenyan Election. Her articles have appeared in Foreign Policy, New Internationalist, Al-Jazeera, and Project Syndicate, among others. On Twitter: @Nanjala1.