Among the Ruins

Touring the ruins of Syria.

Among the Ruins: Syria Past and Present. By Christian Sahner. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014. 256 pp.

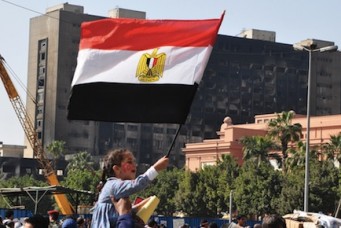

Six years ago, before the uprising-turned-civil-war, saying that “all of Syria is ruins” meant something else. It was a refrain I heard often, as a matter of national pride, on road trips around Syria—in a bus along the Mediterranean with a beaming Kurdish driver, or in a little rental car on a dusty desert road near the Euphrates, through territory now controlled by the jihadi militants who call themselves the Islamic State. “All of Syria is ruins,” architects, historians, farmers, tour guides, shopkeepers, and other Syrians proclaimed of their country, with its remnants of so many civilizations and empires stretching back five thousand years: Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and various Islamic ones, from the Umayyads to the Ottomans.

Today, of course, much more of Syria is in ruins, not because of time but because of barrel bombs and shelling by President Bashar Al-Assad’s regime, and fighting between regime forces and scattered rebels in contested neighborhoods from Aleppo to Damascus. In that gap between new and old ruins, however, is an under-examined reality of Syria’s long history and recent tragedy—and perhaps even a case for some hope amid the carnage.

That’s because Syria’s long history is in part one of social, political, and religious accommodation and evolution. For Christian Sahner, studying medieval and early modern Syrian history was a way “to understand a society in a near constant process of change,” as he writes at the outset of Among the Ruins: Syria Past and Present. “By dint of its strategic location between Europe and Asia and between the traditional domains of Christendom and Islam, it had experienced its fair share of cultural and political shifts through the centuries. Amidst these changes, Syria had become a witness to the manner in which old begets new, and new preserves old.”

A hybrid travelogue, memoir, and history, Sahner’s book is a young historian’s long view of the Syrian civil war, based on his years, from 2008 to 2013, living on-and-off in Syria and Lebanon, where he studied Arabic and researched the Byzantine and early Islamic periods. Sahner contrasts the sectarianism of the civil war with the reality of religious layering and mixed identities that mark Syrian culture.

His account of connecting Syria’s past to its present is often told through the country’s rich urban and architectural heritage, interspersed with his own stories of life in Damascus during the city’s more recent and relative prosperity. In the late 2000s, the capital’s Old City was busily being refurbished, its Ottoman-era courtyard houses made into boutique hotels and restaurants. That newfound prosperity, for some, along with all the foreign students cradling Arabic books by day and Lebanese beers at night, created the “strange ecology” of the Old City’s Christian quarter, known as Bab Touma, where Christians and Muslims got along, but “much was left unsaid.”

Sahner carefully recorded everything in a leather journal—an object lesson in writing things down. After the regime’s suppression of peaceful protests in 2011 slid the country into civil war, his notes became a record of something else. From his perch in Beirut—the French Institute, where he was studying, had relocated there from Damascus—Sahner realized that the journal “formed a picture of Syrian society on the cusp of a huge upheaval.”

While his effort to mimic travel writers from an earlier era goes awry at times—“the voice of the muezzin at the mosque wasn’t particularly mellifluous,” he confesses of his Old City neighborhood—he often returns to the simple but vital idea that “the deep past exerts a powerful influence on the present” in Syria. That is easy to forget as the country’s borders appear to disintegrate and the conflict descends into a combination of the civil wars in Lebanon and Iraq. But it is necessary to see Syrian history as defined by that long and essential experience of diversity and exchange, a place of Sunni, Shia, Alawite, Druze, Jewish, and various Christian religions as well as Arab, Kurdish, Turkmen, Armenian, and other ethnicities spread widely across the land. It didn’t create some idealized cosmopolitanism, but rather a busy, religiously mixed, multiethnic society that is now being systematically undone, as more than 191,000 people have been killed and millions, including many religious and ethnic minorities, displaced.

With an academic expertise in late antiquity in the Middle East, Sahner gives even the seventh and eighth centuries important proximity. In light of the re-emergence of nihilistic and extremist language from the likes of the Islamic State, which promotes a distorted version of Islam’s past, Sahner’s history is all the more important. “Syrian society then—as today—was divided by linguistic, regional, and sectarian differences,” he writes of the country on the eve of the Islamic conquest, when it was something of a Byzantine backwater. “There were tensions between city and countryside; between Greek metropolitan society and the Syriac culture of the villages; between the Chalcedonian Christianity of the imperial capital, and the Jacobite Christianity of the local ‘non-conformist’ churches. These tensions created a stunning array of ‘micro-climates’ in Syria, but they also made it a difficult place to rule.”

It’s there in the architecture. The Krac des Chevaliers, an intact crusader castle near Homs, is a singular example of medieval architecture, a combination of Frankish and Islamic styles, as it passed from the Knights Hospitaller to the Mamluks in the late thirteen century (though the knights, for their part, took the original fortress from Kurds). Or consider Damascus’ iconic Umayyad Mosque, built atop a first century Hellenic temple to Jupiter and a later Christian church. Of course, the Al-Assad regime and the ruling Baath Party—like other authoritarian governments in the Middle East—have long attempted to co-opt Syria’s culture for their own uses. A plaque outside the Umayyad Mosque commemorating restorations done under Hafez Al-Assad in the 1990s refers to Syria’s former Alawite strongman as al-ra’is al-mu’min, “the believing president.”

That same president didn’t hesitate to flatten the historic city of Hama in 1982 to suppress a Muslim Brotherhood-led revolt—and Bashar has followed his father’s lead. Amid so much violence, Sahner asks: for all of Syria’s differences, is the country’s history one “of unity arising amidst diversity, or unity destroyed by cleavage and division?”

The last three-plus years point to the latter. In the midst of another historical change in Syria, he fears “that much of the country’s past will be forgotten.” From the systematic and wholesale destruction and theft of antiquities in the war to the flight of entire communities, there may be too much to recover.

Frederick Deknatel is an associate editor at World Politics Review. He has written for the Nation,Los Angeles Review of Books, New Republic, and the National, among others. He was a Fulbright Fellow in Syria studying Arabic language and literature from 2008 to 2009. On Twitter: @freddydeknatel.