Social Media Stands as the First Draft of History

As fake news and reality collide, what impact is the current media and political climate having on the initial outline of U.S. contemporary history?

Efforts to understand the appearance of Donald Trump on the global political scene often risk devolving into staid critiques of social media. These theories posit that social media platforms are increasing the ignorance and vulnerability of the body politic at a time when dangerous populist ideologies are on the rise. While some of these critiques may have validity, for a deeper study of digital age communication, one need look no further than the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) journalist and historian Alexander Heffner. The host of the PBS show The Open Mind and the co-author of A Documentary History of the United States, Heffner believes that the spread of digital media has led to a state of viral deception in terms of global public discourse where false concepts such as “fake news” gain traction among a sizable percentage of the population.

In a webinar moderated by Professor Firas Al-Atraqchi, chair of the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) Journalism and Mass Communication Department on December 7, Heffner drew stark lines between what he called history and fake news. History is made of real events while fake news is the lie or deceptive spin put on reality in digital media. In seeking to understand the juxtaposition between history and fake news Heffner told AUC students and faculty:“I come at this topic as a professional journalist but one with an eye toward public education.”

Heffner traced the origin of The Open Mind program he currently hosts back to 1955, where it was started not as an entertainment show but one focused on providing the public with knowledge and information. PBS, as the main public television channel in the United States, was conceived at its inception as being an educational based media outlet.

But much has changed since 1955, and what information the world receives now, and through what medium, has transformed human history.

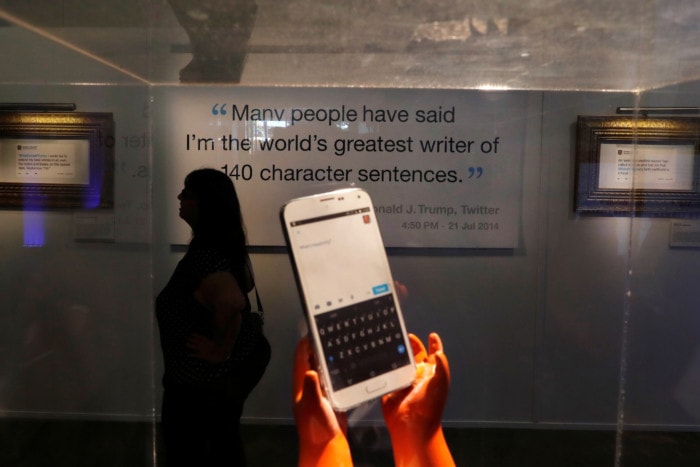

Heffner stressed that social media platforms are now fundamental parts of our modern documentation of the world. “They (social media platforms) are not just influential in that they are the new primary sources of this generation… The reality today is that what is shaping public policy and discourse and what has the potential to persuade people exists in a digital infrastructure.”

Heffner believes that the job of journalists is to discern fake news from what is real history or real events. Yet he underscored that he disliked the term fake news. Instead, Heffner touted a new concept which he coined viral deception.

“The term that we should be using is viral deception, not fake news, because the people who want us to employ the term fake news are often the purveyors and perpetrators of that deception in the context of politics or industry. I think more than ever journalists have to consider themselves, not just the authors of the first draft of history, which has often been said, but that they are the ones who are the investigators, scrutinizing history and deciphering and differentiating between what is fact based and what is fantasy or fiction or propaganda.”

Viral deception is part and parcel to our technological interconnectedness in that it can spread like wildfire because of our instantaneous connectivity.

“It’s not just that we can have a dialogue from continent to continent right now, which is fascinating and ground-breaking and innovative, but it’s the speed, the velocity (at which communication) travels,” said Heffner.

Looking back at the early history of the United States, information was spread with the printed word via pamphlets and newspapers that reached the populace in small towns and villages. While dissemination of information via different media outlets could be full of untruths, the ultimate dissemination of information was much slower 200 years ago due to the obvious level of technology available to spread information.

By the twentieth century, the dueling concepts of misinformation and disinformation came to the fore. The difference between these two concepts, says Heffner, is that, “Misinformation largely was the term accepted and used for the vast majority of the last century. And that implied that people were making earnest mistakes.”

The idea then of misinformation is that it is connected to a plausible mistake. For example, if a person’s words are misquoted and misinformation occurs, the media outlet in question can tell its consumers that the outlet’s journalist made an honest mistake in misquoting a source and the outlet can stress that the mistake itself was not a deliberate one.

However, disinformation is intrinsically deceptive and in our modern context tied to viral deception. Disinformation occurs when a media platform spreads information that is a lie.

In the case of the coronavirus, if a virtual deceptor posts information that is widely shared that it is safe to go into public spaces. This is then considered to be a form of disinformation.

“Telling people to go out into the fields or onto the subway or into crowded facilities when they know, for instance, in the midst of this unprecedented pandemic that the virus is deadly and that it is airborne is disinformation.”

Heffner stressed that at the wrong time and in the wrong circumstances, disinformation, “doesn’t have to be political, it can be medical disinformation but disinformation can be extremely harmful and even lethal.”

Heffner outlined a time in the 20th century when media regulatory commissions were able to, in many countries, fairly parcel out media exposure to politicians and were able to maintain media standards that prevented the mass spread of disinformation. However, with the advent of social media, government regulatory organizations have allowed new digitized media platforms to disseminate information ad hoc. The result has been a divide in the body politic around possible regulation of platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

When Heffnet was asked how regulation can be successful in the realm of social media when individuals on the same social media networks claim the right to freedom of expression, he responded that it will be necessary for media practitioners to create a divide between what he called news personalities and entertainment personalities.

The entertainment personalities can state outlandish ideas for the sake of driving up their like numbers. A news personality online, however, would need to adhere to codified regulations in making news-based claims.

Heffner pointed to Donald Trump’s gaining fame in the entertainment world of reality television and then running divisive and negative presidential campaigns in 2016 and 2020 as examples of how unchecked entertainment media can hurt society.

However, Heffner believes, entertainment media can engender positive change in society:

“It was my idea that you could take two really decent people from the two political parties and bring them together in a reality tv setting… and live with them.” In this way, explained Heffner, entertainment via digital media would be able to be employed in helping society.

When asked whether journalism reporting was being replaced by stating of opinion in the United States, the PBS host said he understood the present trend toward opinion news – such as on CNN and other networks – because this was a way to confront Trump’s false claims to the public. Nonetheless, he acknowledged that the growth of opinion news over the past four years has lowered journalistic standards across the board in the American media.

Heffner argues that President Trump wanted to see lower journalistic standards in U.S. media because, “The climate that Trump wanted to create was one in which Trump was going to war against the media.”

In some ways U.S. Media took the bait offered by Trump and went to war against the president. Yet, Heffner stressed that members of the media were right in attacking Trump and using opinion news against the president because, ultimately, the media’s actions were about the “preservation of truth.”