Will China’s E-commerce Reshape a Reopening World?

China’s advances in digital-buying make the nation a harbinger of how a post-lockdown global economy could look.

A software engineer works on a facial recognition program that identifies people when they wear a face mask at the development lab of the Chinese electronics manufacturer Hanwang (Hanvon) Technology in Beijing as the country is hit by an outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), China, March 6, 2020. Picture taken March 6, 2020. Thomas Peter/Reuters.

For many years, delivery drivers—like so many other workers now deemed essential—blended into the background of daily life around the globe. Despite their ubiquity in an era of inescapable e-commerce platforms, they have often gone widely unseen, unrecognized, and uncared-for by the societies, corporations, and customers they serve.

Yet amid nascent protests by Amazon, Target, and Instacart workers in the United States over the lack of protections during the coronavirus pandemic, a Time Magazine cover—typically reserved for world leaders and influencers from various fields—featured a thirty-two-year-old Beijing-based delivery driver for a March coronavirus special edition. Such recognition is justified, as delivery drivers around the world have provided lifelines to communities, which have relied on them for critical necessities—from foodstuffs to medical and cleaning supplies—during the pandemic.

That delivery driver, employed by the Chinese e-commerce giant Meituan, represents around three million deliverers nationwide in the $65 billion online food delivery market that serves almost six hundred million customers in China. During the pandemic, Meituan’s mobile app, which features 5.8 million merchants in 2,800 Chinese cities, experienced an unprecedented 400 percent increase in demand for online groceries.

China’s e-commerce growth has been driven by the creativity and tenacity of its entrepreneurs and aided by supportive government policies. A sector that was once viewed as a collection of copycats is now producing globally-used apps. With a digital economy valued at $2.3 trillion that makes up 57 percent of global online sales, China’s e-commerce sector is rising to meet the challenges of the coronavirus outbreak and economic recovery. This era of innovation has only been amplified during the pandemic, as online platforms have helped to successfully digitally connect and safeguard the health of a vulnerable, homebound population. Now, paradoxically, even as China’s internet is cut off from most of the world, the country has been making forays to expand its online retail successes on the global market.

These Chinese e-commerce innovations have taken place while the clouds of the coronavirus outbreak and an ongoing trade war have hung over the U.S.–China relationship. Both countries are on the precipice of a new Cold War, and complete decoupling between the world’s two largest economies is being deliberated. In this climate, the natural reaction of the United States would be to shirk China’s e-commerce advances to its shores. However, what does economic decoupling achieve when the American economy is hurting and the Chinese domestic market presents so many growth opportunities for American businesses, particularly in the e-commerce sector? Tracing the growth and development of China’s e-commerce sector, its innovations during the coronavirus lockdown, and the trends in economic reopening, there is little doubt that a U.S. decoupling policy toward China that accompanies an underestimation of Chinese economic resilience at this critical moment would be a grave mistake.

The Growth and Development of China’s E-Commerce Sector

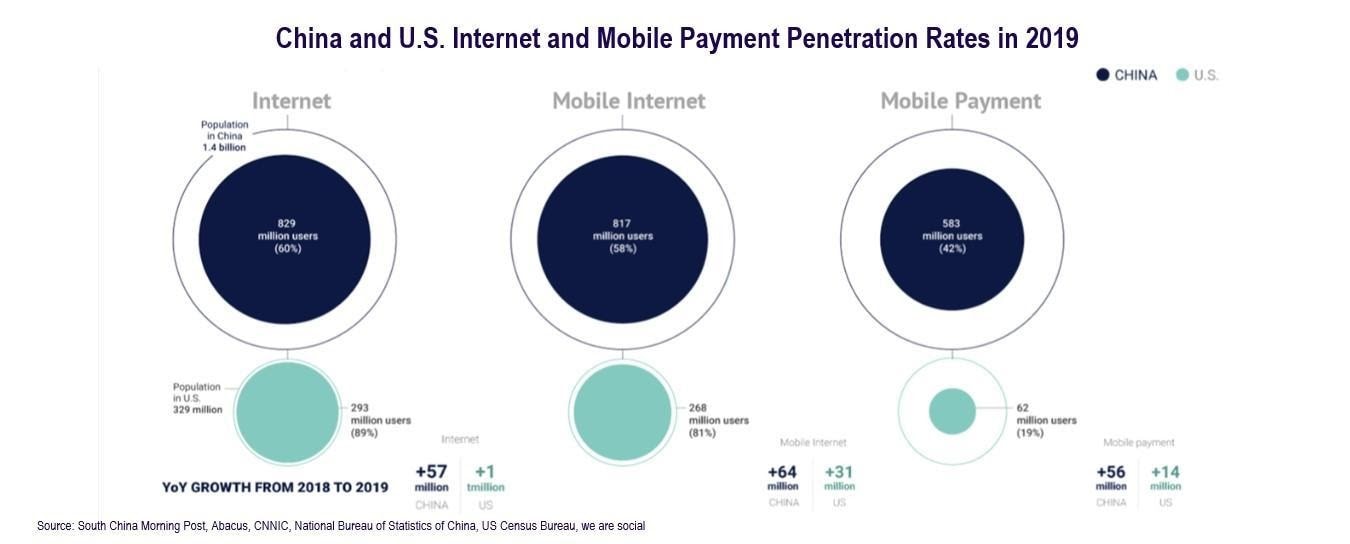

There is an indelible link between the 2003 SARS epidemic and the rise of e-commerce in China. As the SARS outbreak spread throughout the country, the population faced circumstances similar to those of 2020: a homebound population paired with increasingly accessible devices and internet connectivity. China’s embryonic e-commerce sector filled the void, most notably by the iconic emergence of Taobao—an online retail platform run by Alibaba. By 2005, founder Jack Ma led the company to begin marking that period with Ali Day, an annual celebration of the commitment of its four hundred employees working from home to keep the platform afloat. Around the same time, Richard Liu closed his chain of consumer-electronics stores and formed JD.com. These two companies heralded the country’s move to online retailing and advanced logistics networks. When Alibaba and JD.com launched their platforms in 2003, China had around 79.5 million internet users (6 percent of the population). Today, in part fueled by the coronavirus pandemic, that number has exploded to 904 million (64.5 percent of the population). See the chart below for a comparison of the internet and mobile payment penetration rates in China and the United States.

Although several Chinese tech companies were launched by copying foreign companies, their application of digital technology and mobile payments grew to be more advanced, and their intimate knowledge of local culture and consumption behaviors made them more competitive in market share, worker hiring, and financing in China compared to overseas counterparts. The major e-commerce platforms in China today have expanded to include:

- Suning (1990), which has 1,600 brick-and-mortar stores around the country and sells physical merchandise, ranging from home appliances to baby care products;

- JD.com or Jingdong (1998), which is a business-to-consumer marketplace that purchases inventory from brands and operates its own logistics chain;

- Tencent (1998), which developed the social media app WeChat and the WeChat mobile payment system and has financial stakes in JD.com, Meituan, and Pinduoduo;

- Alibaba (1999), which developed the Alipay (Ant Financial) mobile payment system and has two major online retailers: Taobao and Tmall. Taobao was modeled on eBay as a consumer-to-consumer marketplace, whereas Alibaba’s Tmall was established as a business-to-consumer marketplace hosting local and international businesses;

- ByteDance (2012), which is one of the newest entrants to e-commerce and plans to sell products through its internationally-renowned apps, Toutiao and Douyin (Tiktok). Tiktok, which allows users to share short videos and has become particularly popular during the global lockdown, has more than eight hundred million users;

- Meituan-Dianping (2015), which is a merger of Groupon-like voucher sellers Meituan and Dianping and combines food delivery; restaurant, entertainment, and travel booking; and customer reviews into one universal online-to-offline platform; and

- Pinduoduo (2015), which has become widely used in rural areas for its combination of bargain shopping, gaming, and social media, is the largest interactive e-commerce platform in the world and has overtaken JD.com to become the second largest e-commerce site in China behind Taobao.

These e-commerce corporations, their platforms, and the Alipay and WeChat Pay mobile payment systems that have transformed financial transactions would not have been able to expand so rapidly without the ongoing efforts of China’s government to promote improved internet infrastructure throughout the country and the development of global e-commerce. More recently, the government launched a new strategic development plan for “new infrastructure.” The Chinese “new infrastructure” projects include a focus on digital services such as 5G networks, the Internet of Things, and data centers, drastically accelerating the country’s e-commerce advancement.

The Impact of “New Infrastructure” on E-Commerce

The creativity of China’s e-commerce entrepreneurs would not have been rewarded had domestic internet infrastructure—from accessibility to increased speeds—not been prioritized by policymakers at the highest levels.Even as the number of Chinese internet users has skyrocketed over the past two decades, many Chinese living in rural areas remain unconnected, with the country’s internet penetration rate of 64.5 percent lagging far behind the U.S. rate of 89.8 percent. To address this digital divide, in 2015 China’s State Council committed to invest $22 billion by 2020 to expand its broadband coverage to rural areas. To illustrate the rapid speed of Chinese broadband growth, in 2013, 17 percent of both Americans and Chinese were connected to broadband internet. By 2019, 86 percent of Chinese had broadband access compared to only 25 percent of Americans.

Following its broadband improvements, the next advancements on the horizon for China include expanded 5G network infrastructure, cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain technology, all of which will serve to enhance China’s e-commerce sector. In May 2020, Premier Li Keqiang led the State Council in calling to vastly enhance internet infrastructure to spur digital consumption and encourage the development of apps for online working, distance learning, telemedicine, vehicle networking, and smart city technologies. More than $106 billion is expected to be invested in this infrastructure in 2020.

The Chinese leadership has also amplified its promotion of cross-border e-commerce, the value of which exceeded $26.3 billion in 2019 (an increase of 38.3 percent from 2018). In April 2020, President Xi Jinping called for accelerating the growth of globally-oriented e-commerce. To implement these goals, China’s State Council plans to establish forty-six new pilot zones for cross-border e-commerce. in addition to the current fifty-nine pilot zones, where businesses are exempt from value-added and excise taxes.

The private sector has mobilized behind these efforts, with Alibaba allowing U.S. companies to sell through its platforms beginning last summer. In just one year, as of April, the number of Alibaba transactions involving U.S. businesses grew more than 100 percent, and the number of active U.S. buyers increased by 76 percent. The Chinese government has also paved the way for e-commerce innovations during the pandemic in the areas of autonomous delivery, telemedicine, online education, and livestreaming.

E-Commerce Advances During COVID-19

Some technological developments grow out of the need to respond to crises, reflecting the adaptability of innovators, though advanced infrastructure and systems are important prerequisites for success. In the early months of 2020, there was an unassailable advancement of China’s e-commerce platforms while many other sectors of the Chinese economy lay dormant. While online sales dropped 0.8 percent overall when comparing the first quarters of 2019 and 2020, a broader comparison between those first quarters shows impressive year-on-year increases in several categories. For example, sales grew in physical commodities overall (by 5.9 percent); agriculture products (by 31 percent); fresh food (by 70 percent); and household necessities, including kitchenware and fitness equipment (by 40 percent). The growth in these categories was made possible by the creative innovations of e-commerce platforms as well as their ability to keep consumers and employees safe.

If not for the pandemic, China’s tech giants would not have innovated so quickly. Similarly, the government would not have moved so quickly to support their advancements, nor would their innovations have been as widely adopted by society. Their adaptation and success during the pandemic have been helped by the fact that they 1) prioritized the health of their customers and employees by employing subsidies and price freezes on products and implementing safe delivery processes; 2) allowed easier access to medical services by promoting telemedicine and creating COVID-19 test booking platforms; and 3) connected and networked communities by increasing the adoption of online education and livestreaming platforms.

Prioritizing Customer and Employee Health

Beginning in January, JD.com, Alibaba, Taobao, and Suning pledged to freeze prices and offer subsidies for essential medical goods. They were able to do so by maintaining control of supplies through their digital logistics platforms, notwithstanding the Chinese New Year holiday. Alibaba called on manufacturing partners to reopen plants in over fifty-eight cities to increase production of N95 masks and other medical supplies. Firms also instituted new methods for protecting customers and employees and built new physical infrastructure and volunteer networks to help safely distribute deliveries. For Alibaba and JD.com, these procedures included equipping employees with masks, gloves, and disinfectant; requiring daily temperature checks and mandatory disinfections between hand-offs and before final drop-offs; and adding more deposit boxes in gated communities so that customers could avoid interacting with deliverers.

To deliver items to harder-to-reach places, firms ramped up the use of drones and self-driving vehicles. The Antwork drone delivery startup obtained the world’s first drone delivery license granted by the Civil Aviation Administration of China in October 2019, and in February 2020 the company made its first drone delivery of medical supplies to the Xinchang People’s Hospital in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province. The first drone delivery by JD.com during the crisis was to Liuzhuang village in Hebei Province, which required a two-kilometer flight over water that helped circumvent a one hundred-kilometer land journey. JD.com also employed its smart vehicles by sending them to the locked-down Wuhan border, where they were remotely operated from Beijing to make urgent deliveries.

Providing Access to Medical Services

Despite cultural and government policy barriers, there have been great advances in telemedicine in China during the pandemic. Beginning in 2019, the government removed its ban on online sales of prescription drugs, and, during the coronavirus outbreak, allowed telemedicine services to both diagnose and treat patients. As a result, a landscape that had been previously dominated by PingAn’s Good Doctor and Alibaba’s AliHealth has grown to include JD Health, WeDoctor by Tencent, and Dingxiang Doctor. These online medical service providers offer a range of services, from free consultations to free mask and medication distribution.

E-commerce platforms like Alibaba, JD.com, and Tencent took the lead in offering COVID-19 test booking through their healthcare arms. On April 21, AliHealth began by offering testing appointments in ten cities, including Shanghai and Beijing, and JD Health introduced an app facilitating test booking and result distribution within twenty-four hours in Beijing. Tencent’s WeChat also launched booking platforms for COVID-19 tests in Beijing, Guangzhou, and elsewhere.

Connecting and Networking Communities

The pandemic has served as a catalyst for increasing community connections and networks through the rapid adoption of online education and livestreaming. Growth in online education has vastly outpaced expectations because of the pandemic, and the sector is expected to grow 12.3 percent to $61.5 billion this year. China’s EdTech sector had seen growing support from investors and the government before the outbreak. In 2019, the State Council invested $6 billion into AI and tech support for education. China pioneered online education in the coronavirus era by converting classroom education to online education for over 278 million K–12 and college students. By March 2020, China had witnessed a 110 percent increase over late 2018 in the number of users of online education platforms, which grew to 423 million.

Perhaps most significant for China’s economy, livestreaming has generated new sales channels for small merchants, enabling live interaction through which sellers can showcase their products—like clothes, food, and cosmetics—and personally respond to audience questions. Livestreaming began with Baidu’s iQiyi and digital innovator YY, but it has been taken to new heights by ByteDance with Douyin (Tiktok). Between January and March 2020, TikTok was downloaded 315 million times, the most downloads ever for an app in a single quarter, and surpassed two billion all-time global downloads. Similarly, commercial activity around these livestreaming platforms increased, with Taobao posting 160 percent growth and 300 percent more merchants year-on-year in March 2020. Livestreaming has become particularly popular in rural areas, where connection with consumers during the coronavirus has been challenging.

Not all of China’s e-commerce advancements have been positive from the perspective of civil liberties and privacy protection. They have laid bare the precarious nature of the close relationship between the government and tech companies. While China implemented its e-commerce law in January 2019, the country’s legal framework, intellectual property rights protections, and general understanding of the rights and responsibilities of e-commerce platforms remain weak. In the push for cross-border e-commerce, China’s firms lack a strong pool of talent to manage the unique political, economic, and legal environments they will encounter abroad, just as foreign firms will continue to face many barriers to entry and complications with transaction security and logistics in China.

Perhaps most disconcertingly, data privacy is becoming an even greater concern given reports that, during the outbreak, Alibaba’s Ant Financial and Tencent developed an app utilizing digital barcodes to help the government control the movement of people. This feature will continue to live on in the Alipay and WeChat platforms as COVID-19 recedes and the country reopens.

Decoupling in a Reopening Economy?

A warning sign to retailers around the world, Chinese shoppers have generally been slow to return to brick-and-mortar retailers as the economy has reopened. Fear of new localized COVID-19 outbreaks has led to a second wave of closings for retailers and attractions. To help encourage spending, cities are distributing vouchers for use at restaurants and retail outlets, and the government sponsored an online shopping festival featuring one hundred e-commerce companies. These trends point to the fact that e-commerce is not only the future of retail, but also may be a much-needed method to prop up flagging economies. Businesses and customers around the world will continue to rely on online sales as new waves of COVID-19 infections ebb and flow.

Without a doubt, the Chinese government’s initial coverup of the coronavirus and its delay in responding have had tragic consequences for both the Chinese public and the global community. But in its subsequent actions, China has also provided critical lessons on global engagement that many other countries could learn, especially the country’s harnessing of the e-commerce sector to do good for society. While it has had occasional problematic lapses, China’s e-commerce sector outperformed its foreign competitors in several vital ways, including by creating jobs, controlling price gouging, and working to ensure product supply. With these advancements, China is leading the transition to post-pandemic recovery.

The success of China’s e-commerce platforms presents yet another foil for the ongoing American retreat from global leadership and progression toward decoupling. The above examples show that collaborating economically with China could potentially bring welcome advances to America’s own e-commerce ecosystem. One area where U.S.–China decoupling is already made manifest is the divide between the use of mobile payments and credit cards. China is unquestionably the global leader in mobile payments with Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Pay. More than 80 percent of Chinese consumers use mobile payment apps, whereas 80 percent of U.S. consumers rely on credit cards, primarily because of the associated rewards. While the phase one U.S.-China trade deal announced earlier this year cleared some obstacles for Visa and Mastercard in the Chinese market, the card companies have faced years of difficulties. Similarly, American mobile payment providers like Google Pay and Apple Pay have struggled to crack the China market, to the extent that Apple has acquiesced to accepting Alipay in Apple stores in China. Despite the best efforts of both sides to overcome these consumer payment preferences, this dichotomy is unlikely to yield anytime soon.

Shortages of personal protective equipment and medical supplies during the coronavirus crisis have prompted U.S. government leaders to call for forced reshoring of American companies from China, banning sensitive exports to China, instituting further tariffs on Chinese goods, and pulling out of international institutions like the World Trade Organization. While the United States should reevaluate and redistribute its domestic manufacturing capacity and supply chains in light of the coronavirus pandemic, policymakers in Washington must also ensure that any policy changes will help, rather than hurt, American interests in a rapidly changing and perilous global economic environment. With the ongoing desperate need for domestic economic growth in the United States, what is the purpose of ending engagement with China now, when there is so much to be gained economically from collaboration, particularly in the e-commerce sector?

Not a Zero-Sum Competition

From SARS to COVID-19, epidemics have produced uncertainty and economic difficulty, but they have also created new opportunities and transformed business climates—with locked-down consumers and pent-up needs for innovative logistics solutions—from which some of China’s most groundbreaking e-commerce advancements have emerged. These factors—particularly with the rapid growth of China’s e-commerce sector during the time of coronavirus—have produced favorable government policy environments to allow for society’s quick adoption of those innovations, while also propping up domestic and global economies. China’s government is now embracing internet infrastructure development and global e-commerce expansion more than ever before. With a looming global depression, the United States would be wise to avoid being sidetracked by short-sighted economic decoupling with China and consider the opportunities—while avoiding the pitfalls—of the Chinese market.

Unfortunately, there are many inherent and inexorable barriers to that collaboration. But amid the ongoing coronavirus blame game and U.S.–China trade war, everyday people—from American soybean farmers to Chinese live streaming florists—are fighting against the same disease and for the same prosperous future, neither of which is a zero-sum competition. To arrive at that prosperous future, they will need to leverage new technologies to sell and deliver their crops before they die on the vine. U.S.–China collaboration on global e-commerce trade may indeed provide their best bet.

Cheng Li is director of the John L. Thornton China Center and senior fellow in the Foreign Policy program at the Brookings Institution. He is also a director of the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations and a Distinguished Fellow of the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. He has authored and edited many books, including The Power of Ideas: The Rising Influence of Thinkers and Think Tanks in China; Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership; China’s Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation; and Rediscovering China: Dynamics and Dilemmas of Reform, among others. He is the principal editor of the Thornton Center Chinese Thinkers Series published by the Brookings Institution Press.

Read MoreRyan McElveen is Associate Director of the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution, where he serves as its senior administrator, coordinates with the Brookings-Tsinghua Center at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, and conducts research on Chinese politics and society and U.S. foreign policy. He is a member of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, and his writing on foreign affairs has been published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, International Herald Tribune, CNN Opinions, Current History, Lawfare, China-US Focus, and the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Read More