A New Palestinian Strategy

Neither armed struggle nor negotiations have achieved justice and independence. The failure of the latest American mediation effort may give further impetus to another means: civil resistance.

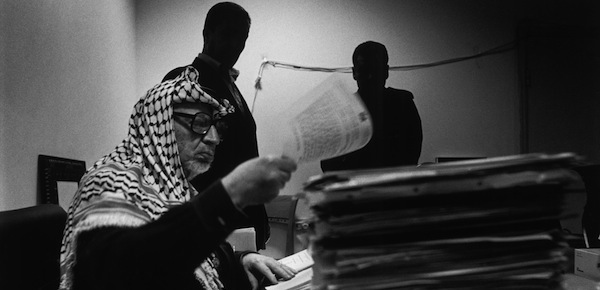

Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, Ramallah, 2002. Paulo Pellegrin/Magnum Photos

Until Secretary of State John Kerry began his intensive efforts to finally resolve the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, politicians on both sides of the conflict were rather pleased with the status quo. The Israeli government succeeded, as a result of the Oslo Accords, to shift responsibility for controlling Palestinian protesters to the Palestinian National Authority. Israelis have also enjoyed an economic boom in part by milking the occupied territories, avoiding paying an economic price for its illegal occupation, and control (directly and indirectly) over millions of Palestinians. For its part, the Palestinian National Authority is delighted that Palestine has a president, a prime minister, passports, an Olympic team, and even postage stamps. These trappings of state were given symbolic international recognition when the United Nations General Assembly voted to recognize Palestine as a non-member state. The vote on November 29, 2012—International Day for Solidarity with the Palestinian People—gave a 138–9 result. The United States, Canada, and Israel were among the no votes.

Yet, the UN vote that gave the Palestinian National Authority the right to call itself the State of Palestine did nothing to change the lot of Palestinians still under the boot of the Israeli army. It did nothing to halt continued Israeli land confiscation and colonization in the West Bank, nor did it lift the unprecedented years-long siege of the Gaza Strip. The UN move did not lead to the suspension of illegal settlement activities or curb the continuing attempts by radical Jewish groups to gain a foothold on the Haram Al-Sharif, site of the sacred Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem’s Old City.

Like so many earlier Palestinian efforts with the UN and other international bodies, this decision did little to produce a tangible change in the status of the occupied territories. In fact, the international community has debated the Palestinian issue ad nauseam without much to show for it. Indeed, international meddling has tended to harm Palestinians rather than help them—dating back to the eve of the First World War when imperial Britain gave contradictory promises regarding the future of Palestine to both Jews and Arabs. A striking illustration of international failure to address Palestinian rights can be seen in a panel of four maps displayed in New York City subway stations and in other cities around the world, which depict the dramatic loss of Palestinian land from 1946 to 2000.

Fatah and Resistance

Palestinians throughout the first half of the twentieth century were largely disorganized, and suffered from internal divisions and factional fighting. Then in 1948 came the nakbah, or catastrophe: the loss of western Palestine in Israel’s War of Independence, and the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem—hundreds of thousands of people who fled the conflict and settled in squalid refugee camps in eastern Palestine (the West Bank) and the Gaza Strip, and in neighboring Arab states.

It took Palestinians a decade to regroup and establish an organized resistance movement. Palestinian activists in Kuwait decided to take things in their own hands, and in 1959 established Harakat al Taharur al Watania al Falastinia, or the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, known by its acronym, Fatah. At the time of Fatah’s launch, the big talking point was the right of return for Palestinian refugees—as called for in UN Resolution 194 adopted in December 1948. Fatah started an underground newspaper called Our Palestine to raise national consciousness among refugees, and on January 1, 1965, announced its first military operation launched from Lebanon. Nonetheless, the group and its leaders—including Yasser Arafat, Khalil Al-Wazir, Salah Khalaf, the Hassan brothers (Said and Hani), and Mahmoud Abbas—remained largely unknown even to the majority of Palestinians.

The devastating Arab defeat in the June 1967 war led to a change of fortunes for the Palestinian resistance movement, which would include a variety of other factions, notably the Marxist-oriented Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), led by George Habash. The defeat of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan—and Israel’s capture of the Sinai Peninsula, Golan Heights and West Bank (until then controlled by Jordan)—galvanized the young guerrilla movement. Fatah began staging frequent resistance attacks from Jordanian territory. One day in the spring of 1968 Fatah fighters, with the help of the Jordanian army, managed to repulse a raid by the Israeli army on a Fatah base in the town of Karameh; when news of the guerrilla victory spread, donations and volunteers poured in. Before long, Arafat and his comrades were able to take over a political structure created by the Arab League—the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

The challenge of leveraging armed resistance in a political strategy became quickly apparent, however. The unruly Palestinian fedayeen irked East Bank Jordanians and posed a threat to Hashemite rule; in 1970, King Hussein’s Bedouin army fought the brief but bloody “Black September” civil war and drove the Palestinian guerrilla fighters out of the kingdom. They regrouped in Lebanon, where they were able to use Palestinian refugee camps as the crucible for revolution and build coalitions with like-minded Arabs unhappy with the ruling regimes in the Arab world. The romantic Palestinian armed struggle coupled with an Arab cultural and intellectual blossoming helped consolidate a Palestinian national movement that would inspire Palestinians inside and outside the occupied territories for years to come. At least for a while, the movement helped restore Arab pride, and even kindled dreams of the Arab renaissance that had once spanned from Iraq to Andalusia.

Yet, while the armed struggle attracted Palestinian, Arab, and even international supporters, it did little to change the balance of forces with Israel, nor did it do much to improve the lives of the refugees. It did bring some hope to Palestinians, and it helped them demonstrate their national identity; in 1974, the Arab League recognized the PLO as the “sole legitimate representative” of the Palestinian people. Arafat had begun to use the armed struggle as a means to a political end. At the United Nations in the same year, the PLO chairman gave a speech from the podium, declaring to the world: “I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom fighter’s gun. Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand.”

Neither the gun nor the olive branch proved decisive. Israel rejected any dealings or negotiations with the PLO; the armed struggle did little to change the equation. Indeed, the “purity” of the freedom fighter’s gun had become increasingly corrupted by the use of violence. Palestinian militants hijacked international airliners in episodes that often ended in fatalities; a group from Arafat’s own Fatah organization masterminded a seizure of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich that left eleven of the Israelis dead. The spectacular exploits, intended to draw attention to the legitimate Palestinian cause, instead boomeranged on the Palestinians. The violence enabled Israel to brand Palestinians as ruthless terrorists who have little regard for innocent civilians.

Intifada

It would take an uprising by young people inside the occupied territories to palpably change the calculus of the struggle. The intifada erupted in Gaza in December 1987, and quickly spread to the West Bank. The images of unarmed teenagers throwing stones at Israeli military forces helped draw attention to the Palestinians as a people fighting for a legitimate cause; lethal Palestinian attacks, albeit in the face of an iron-fisted Israeli response to the intifada, eventually undermined the nonviolent picture. Nonetheless, the popular resistance led inexorably to new political opportunities; in 1993, the Israeli government and the PLO signed the Oslo agreements providing limited self-rule in the occupied territories, and a path to negotiating a final peace accord.

Sari Nusseibeh, a Palestinian professor at Birzeit University in the West Bank, once posed two options to his students: sharing the power, or sharing the land. He explained that sharing the land meant that Palestinians must come to terms with the existence of Israel in historic Palestine; in the two-state solution, Palestinians would have to accept a Palestinian state alongside Israel. Then Nusseibeh offered a provocation: he argued that if the old PLO slogan of a secular state was to be truly implemented, then young Palestinians should call for Israel’s annexation of the West Bank, join the Israeli army, and transform their fight into a civil rights struggle for equality. That shocked the students, and some of them actually attacked Nusseibeh after one of his classes in 1986.

In fact, nonviolent struggle was not new to Palestinians. In 1936, Palestinian Arabs went on a six-month general strike to protest the continued flow of illegal Jewish immigrants into Palestine under the British Mandate. Later, Mahatma Gandhi and the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. would provide tangible proof to the world that nonviolence produces political results. Mubarak Awad, a Palestinian activist who had become an American citizen, returned to Jerusalem in 1985 promoting nonviolence, and created the Palestinian Center for the Study of Nonviolence. His lectures and discussions influenced many Palestinians, including Faisal Husseini, a Fatah leader in Jerusalem and son of Abdel Qader Husseini, one of the most revered Palestinians heroes of the 1948 war, who died fighting in the defense of Jerusalem. Israel deported Awad in 1987.

But Palestinians were not totally convinced of the effectiveness of nonviolence with the Israelis occupiers. They argued that unlike the powers that Gandhi and King confronted in India and the United States, Palestinians faced a militarized settler regime that was neither willing to pull out their soldiers nor provide equal rights to all people under its authority. This realism effectively sidelined the demand for a unitary secular democratic state as outlined in the PLO Charter and by Arafat in his UN address. At the Palestinian National Council meeting in Algiers in November 1988, the PLO accepted an idea that had originated with intifada leaders under occupation to declare a Palestinian state alongside Israel. The slogan that Palestinians were against the occupation and not the State of Israel launched the process that would lead to the signing of the Oslo agreements at the White House—in which Israel recognized the PLO and the PLO recognized Israel.

The Oslo Accords fooled many into believing that resistance (whether violent or nonviolent) was a thing of the past. No one told this to the Islamic movement Hamas, which opposed the peace process. At critical times, such as when Israel was about to withdraw soldiers from certain areas as per the agreement, Hamas launched suicide bomb attacks, often against civilians. Nor was Israel totally on board with Oslo either. Settlement activities continued despite the famous handshake on the White House lawn between Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. The assassination of Rabin by a radical Jewish militant in 1995 proved to be a critical setback to the peace process.

Israel’s ambivalence toward the Oslo agreements following Rabin’s death forced Palestinians to reconsider their strategy. President Bill Clinton, at Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s urging, held a summit at Camp David in 2000 in a last-ditch attempt to salvage the Oslo peace process before the end of his term of office. But Israel’s refusal to halt settlement construction and continuance to deny Palestinian rights in Jerusalem pushed Palestinian leaders to rethink their strategy further.

After the collapse of the Camp David summit, Ariel Sharon, the right-wing leader who aspired to become prime minister, made a provocative visit to the Haram Al-Sharif. Demonstrators hurled stones; Israeli security violently put down the unrest, killing dozens of Palestinians. News of the deaths in Jerusalem spread quickly throughout the occupied territories; another uprising, the Al-Aqsa Intifada, had begun. This time, Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel joined the protests; Israeli security forces killed thirteen Israeli Arabs in the disturbances. An orgy of violence continued for more than two years; suicide bombings struck deep into the heart of Israeli communities, resistance fighters launched guerrilla attacks on Israeli occupation forces, while Israeli troops eventually reoccupied most Palestinian cities and encircled Arafat’s headquarters in Ramallah.

The idea of violent resistance seemed to satisfy various and often competing groups of Palestinians. Left-wing Palestinian revolutionaries romanticized the return of Kalashnikovs and Che Guevara insignias, and resurrected slogans for a secular democratic state. PLO centrists from Arafat’s Fatah movement found themselves obliged to join the new resistance or risk losing their political stature. Militant Islamists fantasized the idea of martyrdom; they carried their attacks into the State of Israel to propagate their view that all of historic Palestine is an Islamic waqf (endowment) that should be liberated by force with the help of mujahideen fighters willing to die in the service of Islam. After Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza in 2006, Hamas launched homemade rockets on Israel—violence that Israel used to justify the massive Operation Cast Lead incursion of Gaza in 2007.

This violence and refusal to recognize Israel’s existence played into the occupier’s hands. Israel constructed a huge separation wall, continued building settlements, and brutally crushed any form of Palestinian resistance, violent or otherwise. Israel became even more hawkish with the election of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and the settler camp increased its influence within the Israeli Knesset. The Israeli peace camp was completely undermined, unable to defend its position in the face of citizens being killed.

The election of Mahmoud Abbas as the president of the Palestinian National Authority following the death of Yasser Arafat in 2004 put Palestinians more firmly on the road of moderation. Abbas represented a realistic platform that rejected what he called the “militarization of the intifada.” His platform was also consistent with the Oslo Accords which he had signed, supporting the two-state solution, coordinating security with Israel, and cooperating with the U.S., Europe, and moderate Arab countries.

However, Abbas’s rejection of violent resistance was not matched with genuine support for nonviolent resistance. Abbas spoke in favor of “popular resistance” and succeeded in getting the sixth Fatah general congress in 2009 to adopt a resolution in favor of “popular struggle.” Hamas leader Khaled Meshal also supported the idea.

In truth, this was little more than lip service. Palestinian leaders from Fatah, Hamas, and the PFLP failed to support the various movements and groups that sprung up to oppose Israel’s wall and other settlement activities through civil disobedience. Palestinian leaders preferred to complain that Oslo’s failure was proof that peaceful actions don’t work. They loved to repeat Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s injunction: “What was taken by force, can only be restored by force.” It was rarely noted that violent actions by Hamas and Fatah in the second intifada failed to get Israelis to change their position or to withdraw from the occupied territories.

The Way Forward

Disillusion with both major Palestinian groups (Fatah and Hamas), including over their failure to reconcile their factional differences, has led many Palestinians in the diaspora to search for ways to get involved in the liberation of their homeland by supporting the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) Movement.

These Palestinians, as well as many inside the occupied territories who support BDS, have not reached a consensus on the political goals of the movement. Some such as Ali Abunimah, author and editor of the Electronic Intifada online publication, argue that Palestinians should push for a single secular democratic state. Others are in favor of using the BDS campaign to pressure Israel into agreeing to a two-state solution that includes the establishment of a viable Palestinian state. Islamic militants inside and outside Palestine continue to believe in the armed jihad despite their lack of success with such an ideology. Hamas, however, appears to be curbing violent attacks at least for the time being, acting often to stop more radical groups from launching rockets from Gaza against Israel.

For now, we can say that the long Palestinian struggle has been reduced to two approaches: the talks on a two-state solution led by the Palestinian National Authority, and the civil resistance movement including BDS. These parties appear to be working separately, although generally with a similar goal. The failure of John Kerry’s intensive diplomatic efforts will certainly provide a wider opening for the still largely leaderless nonviolent movements inside and outside of Palestine.

The era of Arafat and Abbas may be nearing an end. If Abbas ultimately fails to deliver tangible change, Palestinians will undertake a serious re-evaluation of their political strategy. It is incumbent on Palestinians to develop a long-term and agreed-to strategy that can address Palestinian aspirations of both freedom from occupation and independence. Such a strategy will need to take into consideration the aspirations and needs of all Palestinians—not just those living in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, 22 percent of mandatory Palestine. Palestinians including refugees living outside Palestine are a huge force that if properly deployed can be a major asset to any liberation strategy. Ultimately, Palestinians must launch a national process that unifies Palestinians and leverages the enormous energy and resources of more than eleven million Palestinians around the world.

Daoud Kuttab is a regular columnist for Al-Monitor and the Jordan Times. He is the director general of Community Media Network, an NGO supporting independent media across the Middle East and North Africa. He is the recipient of the Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award (1996) and the International Press Institute’s World Press Freedom Hero Award (2000). He resides in Jerusalem and Amman. On Twitter: @daoudkuttab.