A Surplus of Deficits

From a political economy perspective, there are four key forces working against the peace and prosperity of Middle Eastern and North African states. To defeat them, robust institutions are essential.

Crowds at Al Ataba, a market in central Cairo, Feb.10, 2020. Reuters/Mohamed Abd El Ghany

Political economy looks at how power dynamics govern the allocation of economic resources on international, regional, and national scales. This is not always antithetical to the idea of “free markets” which informs mainstream economics on how resources should be allocated. In fact, “free” price-driven and for-profit exchange can only be conducted within a governance framework that embodies certain power relations and that determines the possibilities and restraints facing market transactions. This ranges from private property and rule of law enforced by states in their national territories to international and regional rules-based trade and investment agreements. Power is hence central and critical in understanding how human societies deal with issues of material provisioning i.e. the economy. Power comes in different guises, either in the institutionalized forms of states, international organizations and other authoritative bodies and discourses or in the un-institutionalized forms of violence and civil and international conflict.

Notwithstanding its exact form, power is decisive in mediating and shaping dynamics like demography, natural resource-management, and political, economic, and social institutions through which cooperation, competition, and conflict are conducted. In this framing article, political economy serves as a lens onto a complex and multilayered reality in the Middle East and North Africa. It strives also to offer some foresight not only about what awaits this troubled region of the world but also how to find a way out of its ongoing ordeals.

Two surpluses and two deficits

I will focus on four big overlapping challenges that face most Middle East and North African countries. MENA’s troubled present seems to be rooted in two surpluses and two deficits, borrowing from the language of economists. First is a population surplus, with one of the world’s highest population growth rates and a youth bulge that overwhelms the capacity of national economies to generate growth and create adequate jobs for the new entrants. The second surplus is in oil and natural gas, which has defined MENA’s mode of insertion into the world’s economy and geopolitics since the end of WWII. Despite these natural riches and some gains in socioeconomic development, the region has fallen short of creating regional and national models for inclusive, equitable and environmentally sustainable development.

Alongside these two surpluses, MENA is facing two major deficits; one is natural while the other is sociopolitical. Severe water and arable land shortages (and hence food insecurity, being the largest net food importer in the world) trouble the region, especially given the demographic pressures mentioned above. This is exacerbated by climate change and the high density of international and civil conflicts in the region. In turn, the remarkable intensity of conflict in MENA is the most dramatic expression of the sociopolitical institutional deficit on all international, regional and national scales. Since the end of the Cold War, the institutional capital that post-independence states once possessed has steadily eroded. This has allowed conflict to flourish in the region, either in the form of inter-and intra-state violence or in recurrent popular protest movements calling for social justice and political and economic inclusion on a generational, ethno-sectarian or tribal and subnational territorial basis.

Institutions are extremely important. They constitute the human instruments for collective cooperation and coordination within and between societies. Institutions refer to formal and informal rules as well as mixes of the two, that govern the behavior of individuals and groups rendering it predictable and reliable. It is hard to imagine economics or politics in the absence of some institutional arrangements. Markets cannot exist unless there are mechanisms for information circulation and agreement enforcement. States rely on institutions ranging from organizations and agencies, to political parties and mediating channels with societal groups, in order to assert their authority, build legitimacy and deliver public services.

As functionally important as institutions can be, they are not readymade. They are rather the result of long-term, often unintended and non-teleological, evolution. This makes history central to understanding the presence or absence of institutions and their structures and functions. For a number of historical factors, mainly dating back to the formation of the contemporary MENA after the end of WWII and with the advent of decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s, the region has lacked much of the institutional framework needed to optimize the allocation of economic resources as well as tackle questions of state and human security.

Roots of MENA’s institutional deficit

On the one hand, post-colonial states in MENA assigned themselves the task of modernizing their societies. Whichever institutional capacity and legitimacy they once enjoyed has significantly been dissipated in the past several decades. Indeed, top-down authoritarian modernization has made some strides in areas of social and economic development. However, it has failed remarkably in offering inclusiveness for young and more-educated populations, with higher expectations for economic and political participation. Rounds of fiscal crises, international conditionality, and the implementation of neoliberal measures reinforced exclusion and established stronger ties between wealth and power in the hands of limited elites. This proved exceptionally explosive in cases where elite formation happened along primordial lines, as was the case in Syria, Libya, and Yemen, to mention a few.

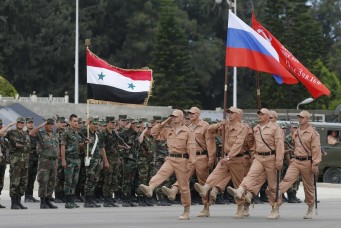

The crisis of the state in MENA is by no means new. But, it has never manifested itself on such a scale and with such intensity as the developments that have unfolded since 2011. Popular uprisings have overwhelmed almost all MENA states, starting from the Arab revolutions of 2011, the upheaval in Turkey as of 2013, the second wave of the Arab uprisings in 2019, and all the way to the recent—and still ongoing—turmoil in Iran. The rise in civil protest and anti-regime popular mobilizations has ushered the region into an extended period of intra- and inter-state conflict in Libya, Syria, Yemen, and Iraq. These dynamics have debilitated national states further and provided regional and global dynamics to civil conflict, converting many broken states into battlefields for competing outside powers.

On the other hand, MENA has historically lacked the institutional capital for regional cooperation. Not only has geopolitics, due to oil abundance and the existence of Israel, made the region home to colonial and neocolonial interventions, unlike any other region in the world (with the possible exceptions of Central America and the Sahel in Africa), but even the potential for intra-regional economic cooperation was often wasted. For instance, the heavy capital-labor exchange between oil-rich, population-poor Arab countries and population-rich, oil poor ones since the oil boom of 1973 onward has not culminated in the creation of institutionalized, long-term, and deep regional integration. Intra-MENA trade and investment flows are still negligible compared to Latin America and East Asia, not to mention Europe or North America.

It is safe to say that the absence of the “right” set of institutions has wasted the potential of optimally using the oil and gas riches of the region for long-term and sustainable development. It is not that MENA has recorded no socioeconomic accomplishments, for it has. Since independence in the 1950s and 1960s, the region has made some significant advances in areas of socioeconomic development including life expectancy, educational attainment and per capita income. Using Human Development Indicators (HDI), MENA’s record would put it in the middle between East Asia and Latin America on the one hand and South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa on the other. Most of these advances, however, were heavily dependent on the region’s role as a major exporter of raw materials. They did not contribute much to redefining how the Middle East and North Africa relate to the rest of the world by diversifying economies, building competitiveness and increasing labor productivity. For four decades or more, MENA has failed to redefine its mode of insertion into the global division of labor. Its development, as well as much of its political arrangements nationally and regionally, remained reliant on continued access to oil and gas rents. This could inform us on why the region has failed overall in the creation of vibrant and dynamic, labor-intensive, as well as skill-intensive and high-value-added, economic sectors that could have absorbed the increasingly educated young men and women looking for meaningful employment.

Oil and natural gas have also been a curse exacerbating conflict within, between, and over the MENA almost since their discovery in the 1950s. They have perpetuated the institutional void, otherwise needed for regional and international cooperation and coordination in areas of economy and security. Structural features, like rentierism—wherein a state derives most of its national revenue from the sale of domestic resources to external clients—and oil dependency, contributed to rampant corruption, patronage, and state capture. Because oil and gas extraction do not create many jobs or encourage the growth of other sectors, they have exacerbated an exclusionary model inherently incapable of creating enough good jobs, amid not only greater demographic pressures but also higher expectations by a more educated youth.

It is hard to imagine that such a sad state of affairs would render MENA in a good position to deal with its demographic surplus, and water and arable land shortages. Ecological explanations have been given for some of MENA’s most terrible conflicts in the Sudan and Syria which coincided with extended periods of drought and an intensifying conflict over arable land and water supplies. Access to fresh water is increasingly becoming an issue of regional contention: the two prime examples are of Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia feuding over the Renaissance Dam on the Nile River; and the tension over the Tigris and Euphrates rivers between Syria and Iraq on the one hand and Turkey on the other. Water management here requires a high level of institutionalized coordination on an international scale, which is not only absent but is unlikely to be engendered in such a conflict-ridden context.

The final diagnosis is that MENA is currently an area under heavy demographic, economic, and ecological pressures, which have resulted in instability and a high concentration of violent conflicts. Moreover, the region as a whole is becoming less relevant amid declining energy prices and the United States’ ongoing—and seemingly disorderly—disengagement from it, promising further exacerbation of distributional conflict and chaos.

Is there a way out of this?

MENA might be a special region in the world due to its location, oil riches, and colonial, neocolonial, and postcolonial history. It is, however, not unique. Many of the challenges above are commonplace among other places in the Global South, whether with regards to inclusive development after four decades of neoliberal globalization, hampered nation-state building, or derailed democratization efforts. Even when it comes to the current overconcentration of violent conflict in MENA, Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s and Indochina in the 1960s and 1970s witnessed such episodes. We hence have to think of MENA in comparative terms while considering its specific historical conditions.

How can the region make its economic development more inclusive, its national and regional economies diversified away from oil, and its politics more representative and stable and environmentally more sustainable? There is no easy answer. The issue is neither technical nor technocratic. It lies also far beyond the traditional focus on fixing macroeconomic indicators and public finances a la IMF and World Bank models. Nor will subscribing to the globalization orthodoxy help much in an age of de-globalization and with the ideological hegemony of neoliberalism being shaken—perhaps beyond repair—since the meltdown of 2008 and amid the rise of right-wing populism and neo-protectionists in the core economies.

The road is political and the path has already been opened with all the pressure emanating from below—from citizens themselves. Unleashing the development potential is a socio-political issue of economic repercussions, not just vice versa. Enabling entrepreneurship to take root is key, and this has to be indigenous, extending far down to the broad base of private-sector establishments in productive sectors rather than solely targeting foreign direct investment or enclave sectors that have no linkages with the rest of the economy.

Once again, institutions are critical for such transformation to materialize. Regional and national economies in MENA must strengthen institutions that can furnish skill formation and technological upgrading for a majority of economically active individuals and establishments. Access to financial and physical capital is one critical area that requires major regulatory changes to furnish inclusion of the broad base of private enterprises.

This all requires major institutional changes in how states are articulated with society and the economy as well as how MENA states relate to each other. Institutional change is a political issue that has to do with altering state-society relations addressing questions of legitimacy, stability, and representation either through reform or revolution or both. It is a long-term open-ended process that follows no preformed plan.

The good thing is that it already began almost a decade ago, with the popular uprisings of 2011. Despite the immediate negative aftermath of these events—which ushered the region into a series of civil wars, state failure and relapse into authoritarian rule—a long-term and open-ended transformation has started. The most defining feature of this change is the sustained pressure from below for increasing popular participation. All that academics, experts and other members of the intelligentsia can do for now is push in what appears to be the right direction.

Amr Adly is assistant professor of political science at the American University in Cairo. He was as a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center and a project manager at the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law at Stanford University. He is the author of the book, State Reform and Development in the Middle East: The Cases of Turkey and Egypt. His work has appeared in Business and Politics, Journal of Turkish Studies, and Middle Eastern Studies, among others, and contributes regularly to print and online news outlets.

Read More