Hillary the Hawk

Despite Hillary Clinton’s reputation as a liberal, the record suggests her presidency would push America toward a more militaristic approach to the Middle East.

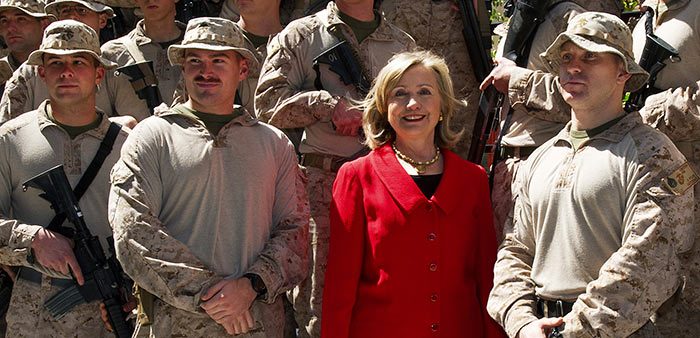

Then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton poses with U.S. Marines at the American Embassy, Cairo, March 16, 2011. Paul J. Richards/Pool/Reuters

Despite being an icon for many liberals and an anathema to the Republican right, former U.S. Senator and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s positions on the Middle East have more closely resembled those of the latter than the former. Her hawkish views go well beyond her strident support for the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and subsequent occupation and counter-insurgency war. From Afghanistan to Western Sahara, she has advocated for military solutions to complex political problems, backed authoritarian allies and occupying armies, dismissed war crimes, and opposed political involvement by the United Nations and its agencies. TIME magazine’s Michael Crowley aptly summed up her State Department record in 2014:

As Secretary of State, Clinton backed a bold escalation of the Afghanistan war. She pressed Obama to arm the Syrian rebels, and later endorsed airstrikes against the Assad regime. She backed intervention in Libya, and her State Department helped enable Obama’s expansion of lethal drone strikes. In fact, Clinton may have been the administration’s most reliable advocate for military action. On at least three crucial issues—Afghanistan, Libya, and the bin Laden raid—Clinton took a more aggressive line than [Secretary of Defense Robert] Gates, a Bush-appointed Republican.

Her even more hawkish record during her eight years in the Senate, when she was not constrained by President Barack Obama’s more cautious foreign policy, led to strong criticism from progressive Democrats and played a major role in her unexpected defeat in the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries.

After stepping down from the helm of the State Department in early 2013, she made a concerted effort to distance herself from Obama’s Middle East policies, which—despite including the bombing of no less than seven countries in the greater region—she argues have not been aggressive enough. It is not surprising, therefore, that the prominent neoconservative Robert Kagan, in examining the prospects of her becoming commander-in-chief, exclaimed to the New York Times in 2014, “I feel comfortable with her on foreign policy.” He elaborated by noting that “if she pursues a policy which we think she will pursue, it’s something that might have been called neocon, but clearly her supporters are not going to call it that. They are going to call it something else.” The same New York Times article noted how neoconservatives are “aligning themselves with Hillary Rodham Clinton and her nascent presidential campaign, in a bid to return to the driver’s seat of American foreign policy.”

If Clinton wins the American presidency in 2016, she will be confronted with the same momentous regional issues she handled without distinction as Obama’s first secretary of state: among them, the civil war and regional proxy war in Syria; the Syrian conflict’s massive refugee crisis; civil conflict in Yemen and Libya; political fragility in Iraq and Afghanistan; Iran’s regional ambitions; the Israel-Palestine conflict; and deteriorating relations with longstanding allies Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. There are disagreements as to whether Clinton truly embraces a neoconservative or other strong ideological commitment to hardline policies or whether it is part of a political calculation to protect herself from criticism from Republicans who hold positions even further to the right. But considering that the Democratic Party base is shifting more to the left, that she represented the relatively liberal state of New York in the Senate, and that her 2008 presidential hopes were derailed in large part by her support for the Iraq war, it would probably be a mistake to assume her positions have been based primarily on political expediency. Regardless of her motivations, however, a look at the positions she has taken on a number of the key Middle East policy issues suggest that her presidency would shift America to a still more militaristic and interventionist policy that further marginalizes concerns for human rights or international law.

Voting for War in Iraq

Hillary Clinton was among the minority of congressional Democrats who supported Republican President George W. Bush’s request for authorization to invade and occupy Iraq, a vote she says she cast “with conviction.”As arms control specialists, former United Nations weapons inspectors, investigative journalists, and others began raising questions regarding the Bush administration’s claims about Iraq having reconstituted its chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons programs and its chemical and biological weapons arsenals, Clinton sought to discredit those questioning the administration’s alarmist rhetoric by insisting that Iraq’s possession of such weapons and weapons programs were not in doubt. She said that “if left unchecked, Saddam Hussein will continue to increase his capacity to wage biological and chemical warfare, and will keep trying to develop nuclear weapons.” She insisted that there was a risk that, despite the absence of the necessary delivery systems, Saddam Hussein would somehow, according to the 2002 resolution, “employ those weapons to launch a surprise attack against the United States,” which therefore justifies “action by the United States to defend itself” through invading and occupying the country.

As a number of prominent arms control analysts had informed her beforehand, absolutely none of those charges were true. The pattern continued when then-Secretary of State Colin Powell in a widely ridiculed speech told the United Nations that Iraq had close ties with Al-Qaeda, still had major stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons, and active nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons programs. Powell himself later admitted his speech was misleading and filled with errors, yet Clinton insisted that it was nevertheless “compelling.”

In an apparent effort to convince her New York constituents, still stung by the September 11 attack thirteen months earlier, of the necessity of war, she was the only Democratic U.S. senator who made the false claim that Saddam Hussein had “given aid, comfort, and sanctuary” to Al-Qaeda, an accusation that even many fervent supporters of the invasion recognized as ludicrous. Indeed, top strategic analysts had informed her that there were no apparent links between Saddam Hussein’s secular nationalist regime and the radical jihadist Al-Qaeda. Indeed, doubts over such claims appeared in the U.S. National Intelligence Estimates made available to her and in a definitive report by the Department of Defense after the invasion. These reports not only confirmed that no such link existed, but that no such link could have been reasonably suggested based upon the evidence available at that time.

Clinton’s defenders insist she was misled by faulty intelligence. She admitted that she did not review the National Intelligence Estimate that was made available to members of Congress prior to the vote that was far more nuanced in their assessments than the Bush administration claimed. (She claimed that the authors of the report, including officials from the State Department, Central Intelligence Agency, and Department of Defense, had briefed her: “I felt very well briefed.”) She also apparently ignored the plethora of information provided by academics, independent strategic analysts, former UN inspectors, and others, which challenged the Bush administration’s claims and correctly noted that Iraq had likely achieved at least qualitative disarmament. Furthermore, even if Iraq had been one of the dozens of countries in the world that still had stockpiles of chemical and/or biological weapons and/or a nuclear program, the invasion was still illegal under the UN Charter, according to a consensus of international law experts as well as then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan; it was also arguably unnecessary, given the deterrence capability of the United States and well-armed Middle Eastern states.

Despite wording in the Congressional resolution providing Bush with an open-ended authority to invade Iraq, Clinton later insisted that she voted for the resolution simply because “we needed to put inspectors in.” In reality, at the time of vote, the Iraqis had already agreed in principle to a return of the weapons inspectors and were negotiating with the United Nations Monitoring and Verification Commission on the details which were formally institutionalized a few weeks later. (Indeed, it would have likely been resolved earlier had the United States not repeatedly postponed the UN Security Council resolution in the hopes of inserting language which would have allowed the United States to unilaterally interpret the level of compliance.) In addition, she voted against the substitute amendment by Democratic Senator Carl Levin of Michigan, which would have also granted President Bush authority to use force, but only if Iraq defied subsequent UN demands regarding the inspections process. Instead, Clinton voted for the Republican-sponsored resolution to give President Bush the authority to invade Iraq at the time and circumstances of his own choosing regardless of whether inspectors returned. Unfettered large-scale weapons inspections had been going on in Iraq for nearly four months with no signs of any proscribed weapons or weapons facilities at the time the Bush administration launched the March 2003 attack, yet she still argued that the invasion was necessary and lawful. Despite warnings by scholars, retired diplomats, and others familiar with the region that a U.S. invasion of Iraq would prove harmful to the United States, she insisted that at U.S.-led takeover of Iraq was “in the best interests of our nation.”

Rather than being a misguided overreaction to the 9/11 tragedy driven by the trauma that America had experienced, Clinton’s militaristic stance on Iraq predated her support for Bush’s invasion. For example, in defending her husband President Bill Clinton’s four-day bombing campaign against Iraq in December 1998, she claimed that “the so-called presidential palaces … in reality were huge compounds well suited to hold weapons labs, stocks, and records which Saddam Hussein was required by the UN to turn over. When Saddam blocked the inspection process, the inspectors left.” In reality, there were no weapons labs, stocks of weapons, or missing records in these presidential palaces. In addition, Saddam was still allowing for virtually all inspections to go forward. The inspectors were ordered to depart by her husband a couple days beforehand to avoid being harmed in the incipient bombings. Ironically, in justifying her support for invading Iraq years later, she would claim that it was Saddam who had “thrown out” the UN inspectors. She also bragged that it was during her husband’s administration that the United States “changed its underlying policy toward Iraq from containment to regime change.”

What distinguishes Clinton from some of the other Democrats who crossed the aisle to support the Republican administration’s war plans is that she continued to defend her vote even when the rationales behind it had been disproven. For example, in a speech at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York in December 2003, in which she underscored her support for a “tough-minded, muscular foreign and defense policy,” she declared, “I was one who supported giving President Bush the authority, if necessary, to use force against Saddam Hussein. I believe that that was the right vote” and was one that “I stand by.” Similarly, in an interview on CNN’s Larry King Live in April 2004, when asked about her vote in favor of war authorization, she said, “I don’t regret giving the president authority.”

As it became increasingly apparent that her rationales for supporting the war were false, U.S. casualties mounted, the United States was dragged into a long counter-insurgency war, and the ongoing U.S. military presence was exacerbating sectarian violence and the threat from extremists rather than curbing it, Clinton came under increasing pressure from her constituents to call for a withdrawal of U.S. forces. She initially rejected these demands, however, insisting U.S. troops were needed to keep fighting in order to suppress the insurgency, terrorism, and sectarian divisions the invasion had spawned, urging “patience” and expressing her concern about the lack of will among some Americans “to stay the course.” She insisted that “failure is not an option” in Iraq, so therefore, “We have no option but to stay involved and committed.” In 2005, she insisted that it “would be a mistake” to withdraw U.S. troops soon or simply set a timetable for withdrawal. She argued that the prospects for a “failed state” made possible by the invasion she supported made it in the “national security interest” of the United States to remain fighting in that country. When Democratic Congressman John Murtha of Pennsylvania made his first call for the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq in November of that year, she denounced his effort, calling it a “a big mistake” and declared, “I reject a rigid timetable that the terrorists can exploit.” Using a similar rationale as was used in the latter years of the Vietnam War, she declared, “My bottom line is that I don’t want their sons to die in vain,” insisting that, “I don’t think it’s the right time to withdraw” and that, “I don’t believe it’s smart to set a date for withdrawal.” In 2006, when Democratic Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts (her eventual successor as secretary of state) sponsored an amendment that would have required the redeployment of U.S. forces from Iraq by the middle of 2007 in order to advance a political solution to the growing sectarian strife, she voted against it. Similarly, on Meet the Press in 2005, she emphasized, “We don’t want to send a signal to insurgents, to the terrorists, that we are going to be out of here at some, you know, date certain.”

Two years after the invasion, as the consensus was growing that the situation in Iraq was rapidly deteriorating, Clinton still defended the war effort. When she visited Iraq in February 2005 as a U.S. senator, the security situation had gotten so bad that the four-lane divided highway on flat open terrain connecting the airport with the capital could not be secured at the time of her arrival, requiring a helicopter to transport her to the Green Zone, but she nevertheless insisted that the U.S. occupation was “functioning quite well.” When fifty-five Iraqis and one American soldier were killed during her twenty-four-hour visit, she insisted that the rise in suicide bombings was somehow evidence that the insurgency was failing. As the chaos worsened in subsequent months, she continued to defend the invasion, insisting, “We have given the Iraqis the precious gift of freedom,” claiming that whatever problems they were subsequently experiencing was their fault, since, “The Iraqis have not stepped up and taken responsibility, as we had hoped.”

Clinton finally began calling for the withdrawal of U.S. troops when she became a candidate for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination, but she was critical of her rival Barack Obama’s longstanding antiwar stance. Even though Obama in 2002 (then a state senator in Illinois) had explicitly supported the ongoing international strategy of enforcing sanctions, maintaining an international force as a military deterrent, and returning UN inspectors to Iraq, Clinton charged in a nationally televised interview on Meet the Press on January 14, 2008, that “his judgment was that, at the time in 2002, we didn’t need to make any efforts” to deal with the alleged Iraqi “threat”—essentially repeating President Bush’s argument that anything short of supporting an invasion meant acquiescence to Saddam’s regime. She also criticized Obama’s withdrawal plan.

Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates writes in his book Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War that Clinton stated in his presence that her opposition to President Bush’s decision in 2007 to reject the bipartisan call of the Iraq Study Group to begin a phased withdrawal of U.S. troops and to instead escalate the number of American combat forces was largely political, given the growing opposition to the war among Democratic voters. Indeed, long before President Bush announced his “surge,” Clinton had called for the United States to send more troops.

Unlike former U.S. Senators John Kerry, Tom Harkin, John Edwards, and other Democratic supporters of the Iraq war resolution, Clinton has never apologized for her vote to authorize force. She has, however, said that she now “regrets” her vote, which she refers to as a “mistake.” Yet, arguments against the Iraq war authorization, virtually all of which have turned out to have been accurate, had been clearly articulated for months leading up to the congressional vote. She and her staff met with knowledgeable people who made a strong case against supporting President Bush’s request, including its illegality under the United Nations Charter, providing her with extensive documentation challenging the administration’s arguments, and warning her of the likely repercussions of a U.S. invasion and occupation.

“All Options on the Table”

Saddam’s Iraq is not the only oil-rich country towards which Clinton has threatened war over its alleged ties to terrorists and Weapons of Mass Destruction. She long insisted that the United States should keep “all options on the table”—clearly an implied threat of unilateral military force—in response to Iran’s nuclear program despite the illegality under the UN Charter of launching such a unilateral attack. Her hawkish stance toward Iran, which is a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and has disavowed any intention of developing nuclear weapons, stands in contrast with her attitude toward countries such as Israel, Pakistan, and India which are not NPT signatories and have already constructed nuclear weapons. She has shown little regard for the danger of the proliferation by countries allied with the United States, opposing the enforcement of UN Security Council resolutions challenging the programs of Israel, Pakistan, and India, supporting the delivery of nuclear-capable missiles and jet fighters to these countries, and voting to end restrictions on U.S. nuclear cooperation with countries that have not signed on to the NPT.

Clinton has nonetheless insisted that the prospect of Iran developing nuclear weapons “must be unacceptable to the entire world”—challenging the nuclear monopoly of the United States and its allies in the region would somehow “shake the foundation of global security to its very core,” in her view. In 2006, she accused the Bush administration of failing to take the threat of a nuclear Iran seriously enough, criticized the administration for allowing European nations to lead diplomatic efforts, and insisted that the United States should make it clear that military options were still being actively considered. Similarly, during the 2008 presidential campaign, she accused Obama of being “naïve” and “irresponsible” for wanting to engage with Iran diplomatically. Not only did she promise to “obliterate” Iran if it used its nonexistent nuclear weapons to attack Israel, she refused to rule out a U.S. nuclear first strike on that country, saying, “I don’t believe that any president should make any blanket statements with respect to the use or non-use of nuclear weapons.”

As with Iraq, she has made a number of alarmist statements regarding Iran, such as falsely claiming in 2007 that Iran had a nuclear weapons program, even though International Atomic Energy Agency and independent arms control specialists, as well as a subsequent National Intelligence Estimate, indicated that Iran’s nuclear program at that time had no military component. Clinton supported the Kyl-Lieberman Amendment calling on President Bush to designate the Iranian Revolutionary Guard as a terrorist group, which the Bush administration correctly recognized as an irresponsibly sweeping characterization of an organization that also controls major civilian administration, business, and educational institutions. The amendment declared that “it should be the policy of the United States to combat, contain, and roll back the violent activities and destabilizing influence … of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” language which many feared could be used as a de facto authorization for war.

Her hawkish stance towards Iran continued after she became Obama’s first secretary of state in 2009. In Michael Crowley’s 2014 story in TIME, Obama administration officials noted how she was “skeptical of diplomacy with Iran, and firmly opposed to talk of a ‘containment’ policy that would be an alternative to military action should negotiations with Tehran fail.” Clinton disapproved of the opposition expressed by Pentagon officials regarding a possible U.S. attack on Iran because she insisted “the Iranians had to believe we would use force if diplomacy failed.” In an August 2014 interview with the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg, when she was no longer in the administration, she took a much harder line on Iranian nuclear enrichment than the United States and its negotiating partners recognized was realistic, leading some to suspect she was actually pushing for military intervention.

Clinton, by then an announced candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, did end up endorsing the 2015 nuclear agreement. Opposing a major foreign policy initiative of a sitting Democratic president, especially one with strong Democratic support, would have been politically untenable. Yet, Clinton’s hardline views toward the Islamic Republic remain palpable. For example, in a speech in September 2015 at the Brookings Institution, she claimed that Iran’s leaders “talk about wiping Israel off the face of the map”—a gross distortion routinely parroted by hardliners in Washington. The original statement was uttered by revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini a quarter century earlier and quoted in 2005 by then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (who left office in 2013). Moreover, there is no such idiom in Farsi for “wiping off the map.” Khomeini’s statement was in a passive tense and asserted his belief that Israel should no longer be a Jewish nation state, not that the country’s inhabitants should be annihilated. Yet, during her speech, Clinton kept repeating for emphasis, “They vowed to destroy Israel. And that’s worth saying again. They vowed to destroy Israel.”

Clinton often seems oblivious to the contradictions in her views and rhetoric. For example, to challenge Iran, an authoritarian theocratic regime which backs extremist Islamist groups, she has pledged to “sustain a robust military presence in the region” and “increase security cooperation with our Gulf allies”—namely, other authoritarian theocratic regimes like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar, which also back extremist Islamist groups.

She has also repeated neoconservative talking points on alleged Iranian interference in various Middle Eastern conflicts. For example, she has decried Iran’s “involvement in and influence over Iraq,” an ironic complaint for someone who voted to authorize the overthrow of the anti-Iranian secular government of Saddam Hussein despite his widely predicted replacement by pro-Iranian Shiite fundamentalist parties. As a U.S. senator, she went on record repeating a whole series of false, exaggerated, and unproven charges by Bush administration officials regarding Iranian support for the Iraqi insurgency, even though the vast majority of foreign support for the insurgency was coming from Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries and that the majority of the insurgents attacking U.S. occupation forces were fanatically anti-Iranian and anti-Shiite.

She has also gone on record holding “Iran responsible for the acts of aggression carried out by Hezbollah and Hamas against Israel.” Presumably since she realizes that relations between Iran and Hamas—who are supporting opposing sides in the Syrian civil war—are actually quite limited, she has not called for specific actions regarding this alleged link. But she has pledged to make it a priority as president to cut off Iran’s ability to fund and arm Hezbollah, including calling on U.S. allies to somehow block Iranian planes from entering Syria. In addition, notwithstanding the provisions in the nuclear agreement to drop sanctions against Iran, she has called on Congress to “close any gaps” in the existing sanctions on non-nuclear issues.

When Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, her principal rival for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016, suggested taking steps to eventually normalize diplomatic relations with Iran, the Clinton campaign attacked him as being irresponsible and naïve. Despite the fact that the vast majority of U.S. allies already have diplomatic relations with the Islamic Republic, a campaign spokesperson insisted it would somehow “cause very real consternation among our allies and partners.”

Dictators and Democrats

Though bringing democracy to Iraq was one of the rationales Hillary Clinton gave for supporting the invasion of that country, she has not been as supportive of democratic movements struggling against American allies. During the first two weeks of protests in Tunisia against the dictatorial regime of Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali in December 2010, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton expressed her concern over the impact of the “unrest and instability” on the “very positive aspects of our relationship with Tunisia.” She insisted that the United States was “not taking sides” in the struggle between the corrupt authoritarian government and the pro-democracy demonstrators, and that she would “wait and see” before communicating directly with Ben Ali or his ministers. Nearly four weeks after the outbreak of protests, she finally acknowledged some of the grievances of the demonstrators, saying “one of my biggest concerns in this entire region are the many young people without economic opportunities in their home countries.” Rather than calling for a more democratic and accountable government in Tunisia, however, her suggestion for resolving the crisis was calling for the economies of Tunisia and other North African states “to be more open.” Ironically, Tunisia under the Ben Ali regime—more than almost any country in the region—had been following the dictates of Washington and the International Monetary Fund in instituting “structural adjustment programs” privatizing much of its economy and allowing for an unprecedented level of “free trade.”

Just two days after the interview in which she appeared to back the Ben Ali regime, as the protests escalated further, Clinton took a more proactive stance at a meeting in Qatar, where she noted that “people have grown tired of corrupt institutions and a stagnant political order” and called for “political reforms that will create the space young people are demanding, to participate in public affairs and have a meaningful role in the decisions that shape their lives.” By this point, however, Tunisians were making clear they were not interested in simply “political reforms” but the downfall of the regime, which took place the following day.

Clinton took a similarly cautious approach regarding the Egyptian uprising, which began a week and a half later on January 25. In the initial days of the protests, despite the government’s brutal crackdown, she refused to do more than encourage the regime to allow for peaceable assembly. Despite appearances to the contrary, Clinton insisted that “the country was stable” and that the Mubarak government was “looking for ways to respond to the legitimate needs and interests of the Egyptian people,” despite the failure of the regime in its nearly thirty years in power to do so. As protests continued, she issued a statement simply calling on the regime to reform from within rather than supporting the movement’s demand for the downfall of the dictatorship.

After two weeks of protests, Clinton pressed vigorously for restraint by security forces and finally called for an “orderly, peaceful transition” to a “real democracy” in Egypt, but still refused to demand that Mubarak had to step down, insisting that “it’s not a question of who retains power. That should not be the issue. It’s how are we going to respond to the legitimate needs and grievances expressed by the Egyptian people and chart a new path.” On the one hand, she recognized that whether Mubarak would remain in power “is going to be up to the Egyptian people.” On the other hand, she continued to speak in terms of reforms coming from within the regime, stating that U.S. policy was to “help clear the air so that those who remain in power, starting with President Mubarak, with his new vice president, with the new prime minister, will begin a process of reaching out, of creating a dialogue that will bring in peaceful activists and representatives of civil society to … plan a way forward that will meet the legitimate grievances of the Egyptian people.” As the repression continued to worsen and demands for suspending U.S. military assistance to the regime increased, she insisted “there is no discussion of cutting off aid.” As late as February 6, when Mubarak’s fall appeared imminent, Clinton was publicly advocating a leadership role for Mubarak’s newly named vice president. That was General Omar Suleiman, the longtime head of Egypt’s feared general intelligence agency, who among other things had played a key role in the Central Intelligence Agency’s covert rendition program under which suspected terrorists were handed over to third-party governments to be interrogated and in some cases were tortured. In discussions within the Obama administration, she pushed for the idea of encouraging Mubarak to initiate a gradual transition of power, disagreeing with Obama’s eventual recognition that the U.S.-backed dictator had to step down immediately. In her book Hard Choices, a memoir of her tenure as secretary of state written three years later, Clinton noted, “I was concerned that we not be seen as pushing a longtime partner out the door.”

After Saudi Arabian forces joined those of the Bahraini monarchy in brutally repressing nonviolent pro-democracy demonstrators the following month, the Wall Street Journal reported that Clinton had emerged as one of the “leading voices inside the administration urging greater U.S. support for the Bahraini king.” In Yemen, while she eventually called for authoritarian President Ali Abdullah Saleh to step down, she backed the Saudi initiative to have him replaced by his vice president, General Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, rather than support the demands of the pro-democracy movement to allow a broad coalition of opposition activists to form a transition government and prepare for democratic multiparty elections.

Clinton proved an enthusiastic supporter of regime change when it came to dictatorships opposed by the United States, however. While there has been debate regarding the appropriateness and extent of U.S. intervention in Libya and Syria, she consistently allied herself with those advocating U.S. military involvement. She pushed hard and eventually successfully for U.S. intervention in support for rebel forces in Libya, over the objections of key Obama administration officials, including the normally hawkish Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. While the Arab League had requested and the United Nations had authorized the enforcement of a no-fly zone to protect civilians from attack by the forces of dictator Muammar Gadhafi, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces—with Clinton’s encouragement—dramatically expanded their role to essentially become the air force of the rebels. Following the extra-judicial killing of Gadhafi by rebel soldiers, she joked, “We came, we saw, he died,” which some took as an effective endorsement of crimes committed by armed allies against designated enemy leaders.

During the Benghazi hearings in October 2015, when she was asked about that comment, she said it “was an expression of relief that the military mission undertaken by NATO and our other partners had achieved its end.” However, in justifying U.S. military intervention, the Obama administration initially insisted that the goal was “to protect the Libyan people from immediate danger, and to establish a no-fly zone,” not regime change or assassination, underscoring Clinton’s apparent role in dramatically expanding the mission of U.S. forces. The chaos that resulted from the seizure of power by a number of armed militia groups, including Islamist extremists, created a situation where militiamen numbered nearly a quarter million in a country of some six million people. While there appears to be little merit in the Republican accusations against Clinton in regard to her conduct regarding the killing of the U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans in Benghazi by Islamist extremists in September 2012, her role in helping to create the situation that gave rise to such extremists raises more serious questions.

As a U.S. senator, and well before the 2011 uprising in Syria, Clinton was a strong supporter of Republican-led efforts to punish and isolate the Bashar Al-Assad regime. She was a co-sponsor of the 2004 Syrian Accountability Act, demanding that—under threat of tough economic sanctions—Syria unilaterally disarm various weapons systems (similar to those possessed by hostile neighbors), abide by a UN Security Council resolution calling for the withdrawal of foreign troops from Lebanon (which had also been occupied by Israel for twenty-two years without U.S. objection), and return to peace talks with Israel (despite Israel’s categorical refusal to withdraw from the occupied Golan Heights). Her resolution also claimed that the Syrian government was responsible for the deaths of Americans in Iraq and threatened to hold Syria accountable in language that other senators feared could be used by the Bush administration for military strikes.

Not long after the initially nonviolent uprising in Syria turned into a bloody civil war with heavy foreign intervention, the New York Times reported that Clinton pushed hard for the Obama administration to become directly involved militarily in support for Syrian rebels. Irritated that NATO had gone well beyond its mandate in Libya, Russia and China blocked UN action on Syria. Obama eventually agreed with Clinton to begin training and arming some rebels, but despite the half billion dollars invested in the project, only a few dozen rebels made it into the field and they were quickly overrun by rival Islamist rebels of the Al-Nusra Front. Clinton has subsequently insisted that the disorganized and factious nature of the armed secular Syrian opposition notwithstanding, the failure to topple the Syrian regime or contain the rise of Islamist extremists was that the United States did not arm the rebels earlier and more heavily. Indeed, she has essentially blamed Obama for the dramatic rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, saying his failure “to help build up a credible fighting force … left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled.” She has also expressed disappointment that the Obama administration backed down from its threats in 2013 to bomb Syria following the Al-Assad regime’s launch of a deadly sarin gas attack on residential areas near Damascus, even after the government agreed to disarm its chemical weapons.

“Friend” of Israel

During and after her term as a U.S. senator, Hillary Clinton has developed a reputation as one of the most rightwing Democrats on the Israel-Palestine conflict. She has repeatedly sided with Likud-led governments against Israeli progressives and moderates. She has not only condemned Hamas and other Palestinian extremists, but has been critical of the Palestinian Authority (PA) as well. That has bolstered the Israeli right’s contention that there are no moderate Palestinians with which to negotiate.

As a U.S. senator, Clinton defended Israel’s colonization efforts in the occupied West Bank and was highly critical of UN efforts to uphold international humanitarian law that forbids transferring civilian populations into territories under foreign belligerent occupation, taking the time to visit a major Israeli settlement in the occupied West Bank in a show of support in 2005. She moderated that stance somewhat as secretary of state in expressing concerns over how the rightwing Israeli government’s settlement policies harmed the overall climate of the peace process, but she has refused to acknowledge the illegality of the settlements or demand that Israel abide by international demands to stop building additional settlements. Subsequently, she has argued that the Obama administration pushed too hard in the early years of the administration to get Israel to suspend settlement construction. In 2011, Clinton successfully argued for a U.S. veto of a UN Security Council resolution reiterating the illegality of the settlements and calling for a construction freeze. On this issue, that fit a pattern of Clinton’s disregard for the UN Security Council, which was established precisely to be a vehicle for enforcing international law such as in matters of belligerent foreign occupation. “We have consistently over many years said that the United Nations Security Council—and resolutions that would come before the Security Council—is not the right vehicle to advance the goal,” Clinton has said.

The favoritism toward Israel is all the more glaring given America’s failure or unwillingness to stop Israel’s colonization on its own. When the government of Likud Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reneged on an earlier promise of a temporary and limited freeze and announced massive subsidies for the construction of new settlements on the eve of Clinton’s 2011 visit to Israel, she spoke only of the need for peace talks to resume. She equated the PA’s pursuit of its legal right to have Palestine statehood recognized by the United Nations with Israel’s illegal settlements policy as factors undermining the peace process.

While rejecting Palestinian demands that Israel live up to its previous commitments to freeze settlements on the grounds there should be no pre-conditions to talks, Clinton has at times demanded pre-conditions for Arab participation. For example, in response to President Bush’s invitation for Arab states to attend the Annapolis peace conference in 2007, then-Senator Clinton went on record insisting that Arab states wishing to attend should unilaterally “recognize Israel’s right to exist and not use such recognition as a bargaining chip for future Israel concessions” and “end the Arab League economic boycott of Israel in all its forms.” The letter made no mention of the establishment of a Palestinian state, an end to the Israeli occupation, the withdrawal of illegal Israeli settlements, or any other Israeli obligations. As James Zogby of the Arab American Institute put it at the time, “if the goal is for Arab states not to participate in the upcoming conference, this would be the way to go.” The Bush administration rejected her demands for such pre-conditions.

Another example of Clinton’s double standards has been in her pledge as a presidential candidate to increase U.S. military aid and diplomatic support for Israel’s rightwing government. This is a government that includes ministers from far right parties who support violent settler militia that have repeatedly attacked Palestinian civilians, oppose recognition of a Palestinian state, and reject the Oslo Accords and subsequent agreements by the Israeli government. However, Clinton insists, “We will not deal with nor in any way fund a Palestinian government that includes Hamas unless and until Hamas has renounced violence, recognized Israel, and agreed to follow the previous obligations of the Palestinian Authority.”

More recently, Clinton has been making a series of excuses as to why Israel cannot make peace despite the Palestine Authority’s acquiescence to virtually all the demands of the Obama administration. For example, the Washington Post noted how she “appeared to blame the collapse of direct Israel-Palestinian talks on the wave of Mideast revolutions and unrest during the 2011 Arab Spring, although talks had broken off the previous year.” Clinton has also said that Israelis cannot be expected to make peace until they “know what happens in Syria and whether Jordan will remain stable,” which most observers recognize will take a very long time; that line of thinking enables Israel to further colonize the West Bank to the point where the establishment of a viable Palestinian state is impossible. What kind of peace settlement she envisions has not been made clear, but she did endorse then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s 2004 “Convergence Plan,” which would have allowed Israel to annex large areas of Palestinian territory conquered by Israeli forces in the 1967 war, despite the longstanding principle in international law against any country expanding its territory by force and the fact that the plan divides any future Palestinian state into a series of small, non-contiguous cantons surrounded by Israel.

As a U.S. senator, Clinton co-sponsored a resolution which, had it passed, would have established a precedent by referring to the West Bank not as an occupied territory but as a “disputed” territory. This distinction is important for two reasons. The word “disputed” implies that the claims of the West Bank’s Israeli conquerors are as legitimate as the claims of Palestinians who have lived on that land for centuries. And disputed territories—unlike occupied territories—are not covered by the Fourth Geneva Convention and many other international legal statutes. As a lawyer, Clinton must have recognized that such wording had the effect of legitimizing the expansion of a country’s territory by force, a clear violation of the UN Charter.

Clinton has challenged the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In 2004, the world court ruled by a 14-1 vote (with only the U.S. judge dissenting, largely on a technicality) that Israel, like every country, is obliged to abide by provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention on the Laws of War, and that the international community—as in any other case in which ongoing violations are taking place—is obliged to ensure that international humanitarian law is enforced. At issue was the Israeli government’s ongoing construction of a separation barrier deep inside the occupied Palestinian West Bank, which the World Court recognized—as does the broad consensus of international legal scholarship—as a violation of international humanitarian law. The ICJ ruled that Israel, like any country, had the right to build the barrier along its internationally recognized border for self-defense, but did not have the right to build it inside another country as a means of effectively annexing Palestinian land. In an unprecedented congressional action, Senator Clinton immediately introduced a resolution to put the U.S. Senate on record “supporting the construction by Israel of a security fence” and “condemning the decision of the International Court of Justice on the legality of the security fence.” In an effort to render the UN impotent in its enforcement of international law, her resolution (which the Republican-controlled Senate failed to pass as being too extreme) attempted to put the Senate on record “urging no further action by the United Nations to delay or prevent the construction of the security fence.”

Clinton’s claim that “it makes no sense for the United Nations to vehemently oppose a fence which is a nonviolent response to terrorism rather than opposing terrorism itself” was false in that the UN and the world court were only objecting to the barrier being built beyond Israel’s borders. Indeed, in her resolution and elsewhere, she appeared to be deliberately misrepresenting the ICJ’s published opinion, claiming that opposition to the plan of building a barrier in a serpentine fashion deep inside the West Bank as part of an effort to effectively annex large swathes of the occupied territory into Israel was denying Israel its right to self-defense and therefore was proof of an “anti-Israel” bias. In a series of statements and in her resolution, she made no distinction between Israel’s legal right to defend its borders, which the world court upheld, and the land grab to which the court objected.

Clinton has also been an outspoken defender of Israeli military actions, even when the United Nations and reputable international and Israeli human rights groups have documented violations of international humanitarian law. While appropriately condemning terrorism and other attacks on civilian targets by Hamas, Hezbollah, and other extremist groups, she has consistently rejected evidence that Israel has committed war crimes on an even greater scale. For example, since becoming a U.S. senator in early 2001, she has publicly condemned the vast majority of the 135 killings of Israeli children, but not once has she criticized any of the more than 2,000 deaths of Palestinian children.

In the face of widespread criticism by reputable human rights organizations over Israel’s systematic assaults against civilian targets in its April 2002 offensive in the West Bank, Senator Clinton co-sponsored a resolution defending the Israeli actions that claimed they were “necessary steps to provide security to its people by dismantling the terrorist infrastructure in the Palestinian areas.” She opposed UN efforts to investigate alleged war crimes by Israeli occupation forces and criticized President Bush for calling on Israel to pull back from its violent reconquest of Palestinian cities in violation of UN Security Council resolutions.

She has vigorously defended Israel’s wars on Gaza. As secretary of state, she took the lead in attempting to block any action by the United Nations in response to a 2009 report by the UN Human Rights Council—headed by the distinguished South African jurist Richard Goldstone (a Zionist Jew)—which documented war crimes by both Israel and Hamas. She claims that the report denied Israel’s right to self-defense, when it in fact explicitly recognized Israel’s right to do so. Since the report’s only objections to Israeli conduct were in regard to attacks on civilian targets, not its military actions against extremist militias lobbing rockets into Israel, it appears that either she was deliberately misrepresenting the report, never bothered to read it before attacking it, or believes killing civilians can constitute legitimate self-defense.

When Israeli forces attacked a UN school housing refugees in the Gaza Strip in July of 2014, killing dozens of civilians, the Obama administration issued a statement saying it was “appalled” by the “disgraceful” shelling. By contrast, Clinton—when pressed about it in her interview with Jeffrey Goldberg in the Atlantic—refused to criticize the massacre, saying that “it’s impossible to know what happens in the fog of war.” Though investigators found no evidence of Hamas equipment or military activity anywhere near the school, Clinton falsely alleged that they were firing rockets from an annex to the school. In any case, she argued, when Palestinian civilians die from Israeli attacks, “the ultimate responsibility has to rest on Hamas and the decisions it made.”

Clinton’s defense of Israeli war crimes is not restricted to Palestinian-populated areas, but includes those that take place in countries with historically close relations with the United States. During the thirty-four-day conflict between Israeli and Hezbollah forces in 2006, which resulted in the deaths of more than eight hundred Lebanese civilians, she responded to the widespread international criticism of the Israeli attacks on civilian infrastructure and the high civilian casualties by co-sponsoring a resolution unconditionally endorsing Israel’s war on Lebanon. Failing to distinguish between Israel’s right to self-defense and the large-scale bombing of civilian targets far from any Hezbollah military activity, Clinton asked, “If extremist terrorists were launching rocket attacks across the Mexican or Canadian border, would we stand by or would we defend America against these attacks from extremists?” During and after the fighting, Clinton failed to recognize that most critics of the Israeli actions never questioned Israel’s right to self-defense against Hezbollah, but—in the words of a Human Rights Watch report—the “systematic failure by the IDF to distinguish between combatants and civilians” and the way in which “Israeli forces have consistently launched artillery and air attacks with limited or dubious military gain but excessive civilian cost.” The report, echoing a similar report by Amnesty International and other human rights groups, noted how “in dozens of attacks, Israeli forces struck an area with no apparent military target. In some cases, the timing and intensity of the attack, the absence of a military target, as well as return strikes on rescuers, suggest that Israeli forces deliberately targeted civilians.” While tens of thousands of Israelis protested the Lebanon war—which the Israeli government later acknowledged was unnecessary and harmful for Israel—Clinton emerged as one of its biggest cheerleaders. While diplomats at the United Nations were desperately working to end the fighting, Clinton spoke at a rally by rightwing groups outside the UN headquarters in New York City where she praised Israel’s efforts to “send a message to Hamas, Hezbollah, to the Syrians, [and] to the Iranians,” because, in her words, they oppose the United States and Israel’s commitment to “life and freedom.”

Clinton has opposed humanitarian efforts supportive of the Palestinians, criticizing a flotilla scheduled to bring relief supplies to the besieged Gaza Strip in 2011, claiming it would “provoke actions by entering into Israeli waters and creating a situation in which the Israelis have the right to defend themselves.” Not only did she fail to explain how ships with no weapons or weapons components on board (the only cargo on the U.S. ship were letters of solidarity to the Palestinians in that besieged enclave), she also failed to explain why she considered the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of the port of Gaza to be “Israeli waters” when the entire international community recognizes Israeli territorial waters as being well to the northeast of the ships’ intended route. Clinton’s State Department issued a public statement designed to discourage Americans from taking part in the flotilla to Gaza because they might be attacked by Israeli forces, yet it never issued a public statement demanding that Israel not attack Americans legally traveling in international waters. The flotilla never went forward, however, after she successfully convinced the Greek government to deny the organizers the right to sail from Greek ports.

A focus of Clinton has been her insistence that the PA was responsible for publishing textbooks promoting “anti-Semitism,” “violence,” and “dehumanizing rhetoric.” The only source she has cited to uphold these charges, however, has been a rightwing Israeli group that calls itself the Center for Monitoring the Impact of Peace (CMIP). The group, whose board includes Daniel Pipes and other prominent American neoconservatives, was founded to undermine the peace process following the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. CMIP’s claims have long since been refuted, for example in a detailed report released in March 2003 by the Jerusalem-based Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information. The center reviewed Palestinian textbooks and tolerance education programs, and concluded that while the textbooks do not openly or adequately reflect the multiethnic, multicultural, and multireligious history of the region, “the overall orientation of the curriculum is peaceful.” The report said the Palestinian textbooks “do not openly incite against Israel and the Jews and do not openly incite hatred and violence.” The report goes on to observe how religious and political tolerance is emphasized in the textbooks. Similar conclusions have been reached in published reports by the Adam Institute, the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, and Nathan Brown, a political science professor at George Washington University and senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (The books Clinton cited were apparently old Egyptian and Jordanian texts found on some library shelves; they were not currently being used as textbooks nor were they supported by the PA.) Yet Clinton has continued to make these charges, emphasizing that the PA’s “incitement,” which she insists is creating a “new generation of terrorists,” more than Israel’s occupation, repression, and settlements, is the driver of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Here, as in forming her support for the Iraq war, Clinton often seems to rely more on rightwing advocacy groups than she does scholarly research.

The Moroccan Connection

Israel is not the only occupying power in the region supported by Clinton. She has been a strong backer of Morocco’s ongoing occupation of Western Sahara, working with the autocratic Moroccan kingdom to block the long-scheduled referendum on self-determination that would almost certainly lead to a vote for independence. As a recognized self-governing territory (a colony), international law requires that the Sahrawis be given the option of independence, along with other alternatives. Clinton instead has called for international acceptance of Morocco’s dubious “autonomy” plan and for “mediation” between the monarchy and the exiled nationalist Polisario Front, a process that would not offer the people of the territory a say in their future.

Rather than joining Amnesty International and other human rights groups in condemning the increase in the already-severe repression in the Western Sahara, Clinton—in a visit to Morocco in November 2009—instead chose to offer unconditional praise for the Moroccan government’s human rights record. Just days before her arrival, Moroccan authorities arrested seven nonviolent activists from Western Sahara on trumped-up charges of high treason, whom Amnesty International had declared as prisoners of conscience and demanded their unconditional release. Clinton decided to ignore the plight of these and other political prisoners held in Moroccan jails. Not long after Clinton praised the monarchy’s human rights record, the regime illegally expelled Aminatou Haidar, known as the Saharan Gandhi, for her leadership in the nonviolent resistance struggle in Western Sahara. Haidar—a winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award and other honors for her nonviolent activism—spent years in Moroccan prisons, where she was repeatedly tortured. She went on a month-long hunger strike that almost killed her before Morocco relented to international pressure and allowed her to return to her country.

The Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP), a Moroccan government-owned mining company that controls one of the world’s largest phosphate mines in the occupied Western Sahara, was the primary donor to the Clinton Global Initiative conference in Marrakech in May 2015. Exploitation of nonrenewable resources in non-self-governing territories, such as the OCP mining operations, is normally recognized as a violation of international law. This and other support provided to the Clinton Foundation by OCP—now totaling as much as $5 million—has raised some eyebrows, given Hillary Clinton’s efforts as secretary of state to push the Obama administration to take a more pro-Moroccan position. Since leaving office, she has continued her outspoken support for the monarchy. When she announced the Marrakech meeting in the fall of 2014, she praised Morocco as a “vital hub for economic and cultural exchange,” thanking the regime “for welcoming us and for its hospitality.”

President Hillary Clinton?

Increasing numbers of Americans, particularly those who identify with the Democratic Party, are taking a critical view of the militaristic aspects of U.S. policies in the Middle East. It would therefore be somewhat ironic that at a time when polls indicate that a majority of Democrats are increasingly critical of U.S. military intervention in the Middle East and of U.S. support for dictatorial regimes and occupation armies, the party would nominate a candidate who comes from the more hawkish wing of the party. Moreover, should she win the Democratic nomination for president, her Republican opponent in the November election will likely be advocating an even more hawkish policy in the Middle East. In such a scenario, regardless of who becomes president, Americans may end up providing their next president with a mandate for a more militaristic and interventionist policy for a region in the throes of historic upheaval.

Stephen Zunes is professor of politics and international studies and program director of Middle Eastern studies at the University of San Francisco. He is the author of Tinderbox: U.S. Middle East Policy and the Roots of Terrorism; co-author of Western Sahara: War, Nationalism and Conflict Irresolution; and co-editor of Nonviolent Social Movements. He is a writer and senior analyst for Foreign Policy in Focus, associate editor of Peace Review, contributing editor of Tikkun, and the chair of the academic advisory committee for the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. He has contributed to the Nation, Huffington Post, and Alternet. On Twitter: @SZunes.