Iran’s Election: Reality Versus the Dominant Narrative

The primary discourse on Iran’s politics obscures its nuanced reality through binary and inaccurate labels of “moderate” and “hardliner”; examining this framework reveals a deep Western insecurity about Iran’s and the Global South’s rising power

Since the untimely death of Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi in a helicopter crash on May 19, speculation has been rife about the implications of this loss and what the Iranian election process to replace him would deliver. Iran’s geopolitical position as a steadfast champion of resistance against Western and Israeli aggression in a growingly multi-polarised world has made this question one of major importance.

The most striking features of foreign (and domestic) narratives on Iran’s election process and its main actors have been the sheer volume of Western doublespeak reinforced by public misunderstandings. A critical example of this is the use of convoluted yet simplistic terms such as “moderates” and “hardliners” to describe Iran’s two opposing political camps that contested the final vote on July 5.

Indicating Left while Turning Right

Within Iran, the two factions are referred to by the local media as “reformists” and “principalists” (or “ultraconservatives”), which are only slightly more accurate terms than those used by foreign media. In reality, both sides of this Iranian political division have their own deeply held principles and are intent on implementing far-reaching reforms, but in opposite directions. Neither wants to maintain the status quo, economically or socially.

Interestingly, these directions contradict the “right” and “left” distinctions assigned to them in the predominant discourse within Iran. The “reformists” are usually described as representing the “left” when in fact they have been pushing for what may be fairly described as “hard right” neoliberal economic policies and laissez-faireism with a small government and free trade. They have also been in control of the executive branch of government for 24 out of the past 35 years.

These same “moderates” were the faction most active in taking American hostages in 1979, but today are “reformed anti-Americans” who are more likely to be against subsidies and social welfare programs compared to their “hardline” opponents. The “moderates” have been in favour of a free market economy highly fixated—rather oddly—on trading almost exclusively with the West, despite the latter’s crippling sanctions and ill will toward Iran (including the imposition of sanctions on the sale of Western vaccines to Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic). Former President Hassan Rouhani, a reformer, even hesitated to import Chinese vaccines when they were on offer in 2020, having himself earlier insulted the Chinese President Xi Jinping who extended a hand of friendship during his only state visit to Iran in 2016 (despite all the noise to the contrary) at a time when the U.S. regime’s sanctions were causing economic mayhem in the country. In tandem, the Iranian death toll from COVID-19 surpassed 700 a day at its peak, and, despite its natural position as an East-West bridge, Iran is largely (but not fully) bypassed in China’s Belt and Road Initiative today.

It is difficult to imagine a more “hardline” or “fundamentalist” commitment to an economic ideology that effectively tied a suicide vest to Iran’s economy than the policies of Iran’s “moderate reformists”. The country experienced its highest levels of inflation and absolute poverty in its post-revolution history by the end of the last reformist government in 2021, courtesy of the JCPOA (nuclear deal), Trump’s default on the deal, internal corruption, and Iranian moderates’ own anti-welfare drive, which went as far as cancelling social housing programs. At the time, Rouhani announced that the government had “no duty” to build homes for citizens even though land and rent prices had skyrocketed under his administration. Reformist economic policies caused a 1,000 per cent fall in the value of the country’s currency over a period of just eight years (under two successive “moderate” Rouhani administrations, from 30,000 rials to 300,000 rials to the U.S. dollar).

On the cultural front, both the “moderate” and “ultraconservative” governments were equally uninvolved in establishing the “Morality Police” (Gasht-e Ershad), the legislative framework which was developed under former reformist president Muhammed Khatami’s administration. It should be noted that such restrictions on women’s dress codes were initiated soon after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and various governments (i.e. the Executive) have had limited influence on the matter in practice. Changes to hijab rules in the public sphere require changes to existing laws, which fall under the remit of the Legislative branch of government (Majles or Parliament). Some would argue that Constitutional amendments would also be needed.

Ironically, former “hardline” President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (who had also been opposed to the taking of American hostages in 1979) spoke out against the methods of the morality police on several occasions. Yet, it is the “moderates” who, having plunged the country into an economic disaster with the JCPOA “negotiations” and their complete failure to confront and defeat U.S. sanctions (as compared with how Russia has succeeded in the matter), present themselves as the guardians of freedom and women’s rights and were most vocal during the 2022 “woman, life, freedom” turmoil in the country.

Given the above, foreign readers of Iranian affairs would be better informed by viewing Iran’s “ultraconservatives” or “principalists” as Religious Social Democrats (akin to the Mormon Mitt Romney in the United States, Vladimir Putin of Russia, or any number of Christian or Family political parties in Europe). By contrast, the “moderates” or “reformists” should be seen as neoliberals with an inexplicably strong faith in Western corporations, technology, and investment, despite the lessons of Iran’s numerous negative experiences with the West.

The New President

The 69-year-old neoliberal president, Dr. Masoud Pezeshkian, a heart surgeon by profession, was among those who devised and implemented the first hijab requirements in Iranian universities and government buildings back in the early 1980s. As the Minister for Health (2001-2005) under President Khatami, he privatized large parts of Iran’s public health system, causing an exodus of doctors to the private sector, making healthcare unaffordable for many people. As a member of Majles (parliament) for several years, including a period as its Deputy Leader, he has shown no notable record in fighting corruption, although he himself is widely regarded as incorrupt. General neoliberal slogans aside, he presented no specific economic or social welfare plans during his presidential campaign.

Interestingly, he announced on a number of occasions that he did not consider himself to be an expert in anything that can be described as a specialist subject (on any matter), and would be relying on the advice and leadership of “experts” in various fields. It is widely expected (but yet to be determined) that many of his appointees will be neoliberal-minded members of previous neoliberal administrations.

Despite the above, Pezeshkian defeated the Religious Social Democrat Dr. Saeed Jalili whose supporters were smeared as the “Iranian Taliban” with extreme religious views and hidden agendas (contrary to the truth, but likely a main reason for his loss in the elections) by his opponents. Jalili had campaigned on an anti-corruption and pro-transparency ticket with social support and market-based economic development plans for energy, housing, infrastructure, and rural development, among others.

Given the above, it is difficult to see the neoliberals of Iran as being the vanguard of Iran’s national interests or the aims of its revolution. On the contrary, they have repeatedly succumbed to Western bullying by giving up many of Iran’s rights and assets and receiving nothing in return, particularly with regard to the “nuclear deal”.

Their neoliberal policies over the past four decades have created an increasingly unequal and inflation-afflicted economy which has been deliberately corrupted by Western sanctions. For example, barring Iran’s access to international banking systems necessitates trading in secret and in cash or gold or bartering. These imperatives in turn make trade transparency virtually impossible (and dangerous to national security) and encourage corruption and criminality. Were it not for Iran’s immense natural wealth (currently ranked fifth in the world but likely to rise as the world’s second largest lithium deposits were also discovered there in 2023), another decade of neoliberal policies could lead to socio-economic bankruptcy in the country.

Since it is clear that Iran’s political alignments are much more nuanced than their representation in Western media, it is useful to review some key national characteristics, and to examine what Iran’s goals are and how she may achieve them.

Iran’s National Character and Interests

Iranian culture has strong capitalist (private property) and socialist (justice) elements inherent within it, and the 1979 Islamic Revolution’s popular chant “neither Western, nor Eastern, Islamic Republican” is as close as one can get to describing the reality of the country’s dedication to a culture of independence.

Iran is described by many as the oldest country in the world. Whether or not this is factually correct, what is true is that it represents a multicultural, multi-epochal civilisation, similar to, but even older than China, and is not a typical country in the more recent definitions of the term.

Furthermore, Iranian “modern” nationalism can safely be suggested to have predated all other recorded ones in history, as demonstrated by Ferdowsi’s Epic, the Shahnameh, that was completed in 1010 A.D. and includes all characteristics that Western academics falsely claim as exclusively defining “modern” nationalism “invented” by the West (as they so regularly and vulgarly claim with most pre-existing concepts such as human rights—the first Declaration of which was made by the Iranian King Cyrus in 539 B.C.—and democracy). These characteristics, abundantly found in the Shahnameh, include allegiance to a territorially defined nation (a nation-state), and the concomitant love and song and mythology to define and adulate the multicultural, multiethnic, and multilingual nation (with frequent references in the Shahnameh to “Iranzamin”, which translates into “the land of Iran”) served by a king rather than sovereignty being the sole remit of a monarchy, aristocracy, or faith.

By the above standards, Britain is a fading “has-been” clinging on to the lap of the United States, the new kid with terrible manners on the imperial block. This would probably also be how China, with its thousands of years of culture and history, would view such poorly behaved, immature nations.

Iranian pride also partly explains the country’s hitherto reluctance to fully turn East, despite all the apparent enmity from the West. A traditional love for freedom, private property, art, science, and philosophy doesn’t lend itself easily to the (oversimplistic) image Iranians have of communism and its associated Atheism, or to the idea of becoming second-rate allies to any old or new self-appointed “leader” in the world, let alone in Iran’s own backyard.

In the pre-Islamic era of the Persian Empire, Iran’s political and cultural influence extended from the far reaches of Central Asia to China, Yemen, and the Mediterranean, with Rome and Greece being her main rivals. Some would explain Iranian Muslims’ overwhelming adherence to Shia Islam as opposed to Sunnism in this manner (meaning in opposition to Arabs), however, this is hardly a convincing argument since Iran only became majority Shia around the 16th Century. If there was a rivalry involved in the transition, it would have been with the Ottomans rather than Arabs at the time.

Sectarianism, in any shape or form, be it religious or racial, could not be a main part of the equation. Iranians generally do not “get” sectarianism, and today’s political alliance with a majority of Arabs in West Asia (namely, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, as well as Yemen, while having friendly relations with Kuwait, Oman and Qatar, too) stems from the same.

Much fear has been spread about Iran “exporting” its 1979 Islamic Revolution in order to create a new Islamic empire to dominate the region. In fact, this would be the exact opposite of the Revolution’s aims. An actual export of the Revolution would mean helping sovereign countries become free of imperialism. This is exactly why and how Iran and Venezuela, for example, have become such close allies.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution and the building of an empire are mutually exclusive concepts, which is the reason why the United States and its regional colony in the shape of Apartheid Israel are Iran’s worst enemies.

This does not, however, mean that Iran would shy away from confronting its enemies and extending its anti-imperialist influence and power from the mountains and rivers to the seas and oceans all across the region, as is the case today. Quite the opposite—the new president will follow this geopolitically and historically predetermined agenda, willingly or otherwise.

The president’s neoliberal tendencies are hampered by geopolitical realities, lessons from previous negotiations with the West, Israel’s genocidal behaviour, U.S. belligerence, and the Iranian Constitution. The United States has already dismissed Pezeshkian’s peaceful overtures out of hand, and harps on the “nuclear issue” and Iran’s “malign behaviour” per the standard, mind-numbing, imperialist script. The recent assassination of Ismail Haniyeh a few hours after Pezeshkian’s inaugural ceremony in Tehran will further push the president to embrace an anti-Western position at the same time as it solidifies the Axis of Resistance.

In recent years, Iran has become a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and BRICS+, and enhanced its trade with its neighbours in Central Asia through the establishment of a North-South trade corridor to bypass Europe. Gas trade with Turkmenistan was restarted after, rather oddly, having been halted by the “moderate” Rouhani administration, and Turkey has resumed Iranian oil imports in spite of U.S. sanctions. In recent years, for example, neighbouring Afghanistan alone has been a larger export market (3.4% of all exports) for Iranian goods than the whole of Europe put together (3.1% of the same).

As the West loses its hegemonic grip on the world, Iran’s power and influence continue to grow. In the face of such resistance, the West typically brands its opponents as “extremists” while those who are pro-western are described as “moderates” regardless of how barbaric or amoral they might be, per the case of Apartheid Israel today.

The West’s Orwellian Narratives

The terms “moderate” and “hardliner” frequently used in the Western narrative on Iran reveal fascinating and highly consequential links between power and knowledge within today’s Orwellian media landscape and political discourse.

Iranian expatriate “experts” too are just as likely to refer to Iranian politicians as “hardliners” (or “ultraconservatives”) and “moderates” (or “reformists”) as the New York Times, the Jerusalem Post, Al Jazeera, Mossad, or the CIA. This prevailing approach to Iran’s presidential election, for example, provides an opportune and educational case study of how narratives are built and what they aim to achieve. It is important to note that on this particular issue, those referred to as Iranian “moderates” are somewhat more likely to downplay or ignore Western atrocities than the so-called “hardliners”. Apparently, being on the side of ethnocentric Western extremism is “moderate”.

This is not unique to Iran; events in Ukraine (as in the case of the Neo-Nazi Azov Brigade’s influence in the country) and Palestine have revealed that, from a Western perspective, you are a “hardliner” if you do not agree with the West, and there is no other consideration involved. Proven facts or values, such as the human right to life itself, do not enter the debate. Germany now requires all of its new citizens to swear an oath of allegiance to Israel, despite its status as an apartheid state, right in the middle of an ongoing genocide, paid for in large part (cumulatively, since WWII) by Germany and Israel’s other Western allies. Those who do not agree with Germany are branded as “extremists”. According to this logic, Germany is “moderate” and anyone who disagrees is a “hardliner” or even a “terrorist”.

Similarly, accusations of systemic murder and rape of women and decapitation of children only seem to matter when levelled at Palestinians, despite lack of definitive proof, as seen with multiple disproven allegations. Yet, when evidence of sexual violence, collective punishment, decapitation, and genocide of Palestinians appear, Western media is silent.

Attacks on Palestinian schools, hospitals, and refugee camps are ignored by Western regimes; these protected locations are being treated as legitimate targets by Israel with Israeli soldiers boasting about it publicly.

As the West struggles to maintain control of global narratives, its economic and military influence is faltering as well.

The Withering West

The political driver of deviation away from unipolarity to today’s multipolarity can be postulated to have been sparked by an inevitable global response to the warmongering “Coalition of the Willing’s” willful delegitimization of the United Nations through its illegal and genocidal invasion of Iraq back in 2003. This was followed by the global food and fuel crisis of 2007-8 (caused by a long period of accelerated economic growth in the global South leading to supply shortages and price inflation) and a financial crisis in the West (caused by a corrupt U.S. financial sector and unrelated to the former) over the same period. Both of these events revealed clear economic signs of the end of unipolarity.

These events, coupled with constant Western wars of aggression, NATO’s unrelenting expansionism, and the collective punishment of citizens of several countries in the shape of brutal sanctions (despite this being a war crime under the Geneva Convention) which have resulted in millions of casualties and homeless refugees, have led to today’s accelerated decoupling of several countries from the West and (exaggerated and largely Western) fears of a potential world war.

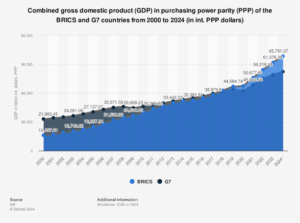

The BRICS+ imperative to de-dollarize global trade on account of Western hubris and its addiction to sanctions resonates strongly with Iran’s interests, and despite existing difficulties, is destined to succeed as the United States’ share of global GDP is on a 60-year-long trajectory of decline, as shown in Figure 1.

Furthermore, the BRICS+ combined share of global GDP already surpassed that of the G7 countries in 2017, as shown in Figure 2 below. BRICS+ will leave the latter behind at an accelerating rate as several more countries such as Malaysia line up to join the group while poorly performing Western economies continue to be tangled in wars and self-harming sanctions.

These trends, the inevitability of which was forecast by many (including this author back in 2008, identifying Russia as the main agent of change), have left the West with two stark choices today: a) to learn to live humbly in harmony with a multipolar world, or b) create chaos and fear of a “world war” to maintain Western delusions of “dominance” that the above charts show to be already and clearly lost.

So far, it appears that the West has opted for the second option, which is likely due to its internal inertia and lack of dynamism together with its misunderstanding of its own military capabilities.

The Military Card

NATO’s genocidal behaviour in recent decades (300,000 deaths in Afghanistan; 1.2 million deaths in Iraq; 14,000 in Libya; an unknown number in the former Yugoslavia; etc.) has exposed both the inherent totalitarian nature of the West vis-à-vis the rest of the world as well as its fundamental weakness in winning wars. While it is likely that since the fall of the Soviet Union NATO has sought to cause permanent wars and chaos around the world (in West Asia, North Africa, and Europe in particular) rather than to win or end wars, it is nevertheless also true that its malign behaviour harms its member states’ individual national interests. The world refugee crisis is one obvious example of this.

It is difficult to identify a single economic or strategic benefit to these warmongering countries emanating from NATO’s all-too-regular genocides, other than direct profits for the military-industrial complex that lives off taxpayer contributions in the order of trillions of U.S. dollars, but contributes relatively little in economic returns. On the contrary, homelessness in the United States has been rising to alarming levels while public healthcare and education go underfunded, and public opinion across the globe has turned sharply against this seemingly psychotic North Atlantic organisation and the countries that belong to it. This includes dissent from within the member states themselves (e.g. Spain, Norway, and Ireland have recently recognised the state of Palestine), not least for their astonishing and proactive involvement in Apartheid Israel’s genocide of Palestinian civilians, livestreamed for a horrified world to witness.

Western insistence on maintaining such violent relations with the rest of the world has resulted in enormous political capital benefits to emerging powers such as China, Russia, and Iran.

Given expansionist NATO’s inability to win or end wars, and Russia and Iran’s successful military collaboration in recent years, including in the Ukraine war, many have concluded that the world is on an inevitable slide toward a new world war. However, this is highly unlikely due to the West’s waning military and economic power as compared to the rest of the world. The West certainly lacks empathy and innovative ideas, and suffers from hubris, inertia, and ignorance, but it is not suicidal.

There will be no world war unless the West means to destroy itself —an unlikely “project” that one has to admit is in fact desired by the so-called “end-timers”, also known as “Christian Zionists”, who see Apartheid Israel as the tool for its realisation. The extent of their influence will be the determinant of whether a world war takes place at the behest of Israel and the West.

Conclusion

Israel’s war on Gaza has exposed a dramatic shift in geostrategic power in the region. Iran is thriving while the West and its colony, Israel—Iran’s existential threats, to be frank—continue to shoot themselves in the foot.

Parallel to the growth of BRICS+ countries, and the inevitable fall in both SWIFT and the U.S. dollar’s prominence in global trade, Iran and her allies too will continue to grow in power and influence, while the United States’s geopolitical sway will significantly weaken in West Asia and elsewhere.

Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that, at some point, there will be an audit of accountability particularly among the Arab states that so shamelessly stood by Israel and the United States during these harrowing times.

Massoud Hedeshi holds a Master’s Degree in Development Studies from Manchester University with two decades of experience in the international aid business, mostly with various UN agencies.

He is a published expert in industrial development and has also been an occasional writer on geopolitics and the changing world order with a focus on West Asia published on Al Jazeera and Asia Times Online.

Read More