Less Than a State

Without a new framework that ensures true sovereignty and security for a future Palestinian state, the two-state solution will remain a farce

One irony of the Hamas-led attack on October 7, and the mass violence meted out by Israel that has followed, is the resurrection in official circles of what is commonly referred to as a “two-state solution”. The majority of the Global South and formerly communist countries have already recognized Palestine as an independent state. Several European holdouts, such as Spain, Norway, and Ireland, have finally joined most of the rest of the world in recognizing a Palestinian state, while others like the United States, France, and the United Kingdom continue to drag their feet. Yet, even those proponents of the two-state solution in the West do not envision a truly sovereign or secure Palestine; instead, these advocates promote a state subjected to Israeli security and political priorities.

In her first remarks on the region since replacing U.S. President Joe Biden as the Democratic presidential candidate in the upcoming elections, Vice-President Kamala Harris declared that she remains “committed to a path forward that can lead to a two-state solution”, emphasizing that, “a two-state solution is the only path that ensures Israel remains a secure, Jewish, and democratic state, and one that ensures that Palestinians can finally realize the freedom, security, and prosperity that they deserve.”

There has been a similar movement in perceptions of the feasibility of a two-state solution among academics who had previously pronounced it dead. In their survey of scholars of the region in the spring of 2023, Shibley Telhami and Marc Lynch reported that 63 percent of academics thought the goal of a “sovereign state of Palestine established within the territories that Israel occupied in the 1967 war” was “no longer possible”. By 2024, however, this number fell to 45 percent, with a drastic increase—from 2 percent to 43 percent—in respondents confident that such a goal was “possible, but improbable in the next ten years”.

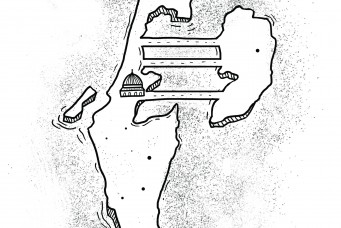

This comes despite movement toward a popular academic consensus that the situation between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, including the continued occupation of Gaza and the West Bank and the constant construction of illegal settlements, constitutes a “one-state reality akin to Apartheid”. This state of affairs is commonly referred to as a “one-state reality”, where there has been a single sovereign state between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea since 1967, when Israel seized the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, along with Egypt’s Sinai and Syria’s Golan Heights.

The reasons cited for the difficulty (or impossibility) of a future two-state solution in a one-state reality that has lasted over half a century have been well rehearsed. They include the presence of some 620,000 well-entrenched Israeli settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, Israel’s wholesale destruction of the Gaza Strip and genocidal mass violence against Palestinians there, and the relegation of roughly two million Palestinian citizens of Israel to the permanent status of second-class citizens.

One reason that is often overlooked, however, is that the so-called “two-state solution” actually only involves one sovereign state: Israel. In other words, the Palestinian state that has been on offer has never been conceived of as sovereign by Israel or the United States. Without actual sovereignty, there can be no two-state solution.

The Issue of Statehood

The Palestinian position, as represented by the Palestinian National Congress (PNC) of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), has transitioned from a strategy of “total liberation”—embodied in the PLO’s much-cited charters of 1964 and 1968—to a position aiming for a single, democratic, and secular state in historic Palestine in the late 1960s and early 1970s, to the eventual acceptance in the 1990s of a Palestinian rump state in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip.

Such a state looked like it might be on the horizon in 1976 when then-newly elected U.S. President Jimmy Carter answered a question about what his administration could do to foster peace in the Middle East by stating that there must be “a homeland provided for the Palestinian refugees who have suffered for many, many years”. But a Palestinian state, much less a sovereign one, was never really on the table. Through a confluence of U.S. domestic pressures, Israeli and American insistence on excluding the PLO from regional negotiations, dogged Israeli determination to settle Palestinian territories, and Egyptian concessions that led to a separate peace, the creation of a Palestinian state was prevented under Carter’s administration.

Instead, Israel’s then right-wing Prime Minister Menachim Begin produced a proposal for Palestinian “autonomy”—which he also referred to as “home rule” or “self-rule” for “the Palestinian Arabs”,—intended to “maintain full Israeli control” over the West Bank and Gaza Strip. This plan (and the assumptions that underpin it) have served, whether explicitly or implicitly, as the basis for Israeli and American conceptions of Palestinian self-determination from the Camp David Accords through today. It is not just Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who has opposed a Palestinian state, other Israeli politicians like opposition leader Benny Gantz and assassinated prime minister Yitzak Rabin have as well. The latter—who has been mythologized by many—explicitly and publicly opposed a Palestinian state in a 1995 speech to the Knesset presenting the Oslo Accords shortly before his assassination by a right-wing Israeli law student:

We view the permanent solution in the framework of the State of Israel which will include most of the area of the Land of Israel as it was under the rule of the British Mandate, and alongside it a Palestinian entity which will be a home to most of the Palestinian residents living in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. We would like this to be an entity which is less than a state and which will independently run the lives of the Palestinians under its authority.

This “entity which is less than a state” is typically what is meant by the second “state” in a two-state solution. Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s “deal of the century” serves as a clear example of this concept, laying out what it called a “realistic two-state solution”:

A realistic solution would give the Palestinians all the power to govern themselves but not the powers to threaten Israel. This necessarily entails the limitations of certain sovereign powers in the Palestinian areas (henceforth referred to as the “Palestinian State”) such as maintenance of Israeli security responsibility and Israeli control of the airspace west of the Jordan River.

Although certainly unintentional, the Trump administration’s quotation marks around “Palestinian State” are appropriate, since such an entity would be a state only in name. A pseudo-state is exactly what the Palestinian scholar Walid Khalidi warned about when he argued for a Palestinian state in the late 1970s. The cornerstone of such a state, he wrote, must be Palestinian sovereignty: “Not half-sovereignty, or quasi-sovereignty or ersatz sovereignty. But a sovereign, independent Palestinian state.” He warned against the sort of Palestinian “state” that has preoccupied advocates of the peace process for the past four decades, describing it as “an Israeli mosaic of Indian reserves and hen-runs, crisscrossed by mechanized patrols and police dogs and under surveillance by searchlights, watchtowers, and armed archaeologists”. It is impossible to see the map proposed by the latest iteration of the two-state solution without recognizing how accurate Khalidi’s description proved to be.

For all its faults, the Trump administration’s plan is at least clear about U.S. and Israeli priorities in Israel/Palestine. Such concerns, which systematically prioritize Israeli conceptions of security over Palestinian sovereignty, have been reproduced time and again in American conceptions of Palestinian self-determination. One recent example includes State Department officials in the Biden administration reportedly looking for a model of Palestinian statehood in the “compacts of free association”, the structure of non-sovereign statehood for U.S. colonial possessions like the Federated State of Micronesia and Palau.

Such hierarchical arrangements are not unique to the U.S. and Israel, of course. Rather than using Micronesia and Palau as a model, U.S. State Department officials could look to Israel’s erstwhile ally, South Africa. Besides the increasingly numerous descriptions of Israel’s 57 years of occupation of the West Bank as apartheid, it is worth comparing Israeli schemes of managing Palestinian self-determination with the Bantustan program laid out in 1959 by M.D.C. de Wet Nel, South Africa’s minister of Bantu Administration and Development. Fearful that the dominant white minority would eventually be “dominated by the political power of the Bantu population”, he saw the creation of non-sovereign Bantustans—some were formally independent and some were autonomous, but all were actually controlled by Pretoria—as a way of managing the rising “demand for self-determination on the part of the non-White nations” of South Africa. Almost all of the Bantustans were non-contiguous inland archipelagos that bear a striking resemblance to the remnants of Palestine in the Trump administration’s Vision for Peace.

Managing the Palestinian right to self-determination while denying Palestinian sovereignty is a goal shared by both proponents of permanent subjugation and Jewish supremacy through so-called Palestinian autonomy (like Menachim Begin and former U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman) as well as proponents of a demilitarized, non-sovereign Palestinian state (like Dennis Ross and the late Martin Indyk). The various plans for either Palestinian autonomy or ersatz statehood differ only in the degree to which Palestinian sovereignty is subjugated to Israeli security concerns. A recent debate on the two-state solution hosted by the U.S.-based think tank the Council on Foreign Relations is instructive on this point. While disagreeing on whether or not Palestinians could ever deserve a state in the first place, former director of Policy Planning Staff of the United States Dennis Ross and former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Elliot Abrams both agree that any Palestinian state would be demilitarized and thus non-sovereign. Likewise, the Clinton parameters from 2000 propose a “non-militarized state” as a compromise between the Israeli demand that Palestine be defined as a “demilitarized state” and the Palestinian position of “a state with limited arms”.

Security and Sovereignty

Why is the question of sovereignty so important in Palestine? It matters because the Palestinian state, once established, would need a guarantee of security, which it clearly cannot get from Israel. The current mass violence perpetrated by Israel in Gaza, the West Bank, and Israel only reinforces the longstanding verity that Israel cannot be trusted to ensure Palestinian security. Besides today’s genocide in Gaza and the current settler violence that Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem describes as “pogroms” aimed at further ethnically cleansing Palestinians from their West Bank villages, there is a throughline of Israeli violence against Palestinians that goes from the Deir Yassin massacre in 1948 through the Rafah massacre in 1956 up to the seemingly never ending death and destruction we are now witnessing. Israeli mass violence in Gaza has become so common over the last two decades that it is referred to as “mowing the lawn”.

A lack of Palestinian sovereignty, whether under the auspices of “home rule” beneath full Israeli sovereignty or within a Palestinian “state-minus” (as proposed by Benjamin Netanyahu and American peace processors), would require Palestinians to be at the mercy of Israel’s military might. This is the same military that has killed tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza since last fall while perpetrating “gang sexual violence and assault” against detained Palestinians in what B’Tselem has described as a “network of torture camps”. It is the same self-described “most moral army in the world” that defends settlers carrying out pogroms in the West Bank, whose soldiers film themselves mocking killed or displaced Palestinian women by dressing in their underwear, and force Palestinian civilians to serve as human shields in military operations. Who could reasonably expect any rational Palestinian to rely on the Israeli military for their security?

Even in scenarios that involve security guarantees by international forces, incidents like the massacre of Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila camps of Beirut have proven such security guarantees to be untrustworthy. The unreliability of the international community has been criticized by scholars of political violence who have begun to ask why the doctrine of the Responsibility to Protect is never exercised to protect Palestinians from Israeli violence. Those who dispute this assessment might ask themselves if they would ever turn to the Israeli state to demilitarize and rely on Palestinians for their security.

The Biden-Harris administration has repeatedly said that it is “committed to promoting equal measures of freedom, justice, security, and prosperity for Israelis and Palestinians alike”. Washington’s insistence on providing a seemingly unconditional and unending supply of weapons and munitions to Israel that are used to destroy Gaza and further the settlement enterprise in the West Bank should definitely put paid to that claim. So far, such rhetoric has remained a diplomatic talking point rather than an actual goal. Despite that, a real commitment to Palestinian security that is not subjugated to Israeli interests should be a guiding principle in any honest attempt to broker a lasting peace in Israel/Palestine.

A Future Past

Plans to partition Palestine have always had an end goal of manufacturing and maintaining an overwhelming Jewish majority as a means of establishing “a national home for the Jewish people”, as laid out in the Balfour declaration and later codified in the British Mandate for Palestine. This was true in the United Nations plan for partition in 1947, and it remains true for conceptions of a so-called two-state solution described by many Americans, Europeans, and Israelis as the only way to ensure Israel remains a “Jewish and democratic state”. Such a goal has long been opposed by Palestinians who understood the Zionist project as an attempt at “turning a majority into a minority in its own country” and “withholding self-government until the Zionists are in the majority and able to profit by it”, Albert Hourani explained on the eve of partition in his testimony to the Anglo-American Committee of Enquiry in 1946. In that same testimony, Hourani also noted with pessimistic foresight shortly before the Nakba that despite the higher birth rates of the Arab demographic majority in Palestine, “there are more ways than one of obtaining a majority”.

Zionist leaders rejected the idea of a pluralistic Palestine as proposed by thinkers like Hourani and George Antonius that would guarantee equal rights to Jews, Muslims, and Christians, instead insisting on exclusively Jewish territorial sovereignty at the expense of the majority, or what the Mandate referred to as the “non-Jewish” population of Palestine. Partition and massive Jewish immigration were meant to cement a Jewish majority in the new state, which was approved by 33 of the then-57 UN member states in the General Assembly in 1947. The ensuing war and ethnic cleansing of over 700,000 Palestinians both expanded Israel’s territory and increased the homogeneity of its population. In 1967, the Israeli state brought to an end the twenty-year interregnum of partition, once again creating a single state, but one that has enshrined exclusive Israeli sovereignty between the river and the sea, as set out in the original Likud platform.

In a move seemingly calculated to embarrass the United States on the eve of Netanyahu’s visit to the White House in July, the Israeli Knesset voted overwhelmingly (68-9) to reject the establishment of a Palestinian state of any kind. Even a non-sovereign Palestinian “state-minus” is apparently a bridge too far for Israel. For the Israelis and their international backers, it seems that historian Walid Khalidi was right that a sovereign Palestinian state that could guarantee Palestinians’ security and “terminate their dependence on the mercy, charity, or tolerance of other parties” remains “unthinkable”. Even Israel’s total rejection of a Palestinian state has not deterred international diplomats from pretending that the peace process still exists, which in practice has served only to give diplomatic cover for Israeli apartheid in the decades since the Oslo Accords. Many Israelis and Americans thought that this status quo, bolstered by normalization with regional autocracies, could continue indefinitely. If the constant Israeli violence against Palestinians did not convince these decision-makers that the status quo is not sustainable, the surprise attack from Gaza by Hamas and its allies surely did. The question, then, becomes whether the actually existing single state between the river and the sea can democratize, giving equal rights to the more than half of the population who are not Jewish.