No-Peace Solution

Peace did not prevail because certain ambiguous provisions contained in the Camp David Accords enabled Israel to deliberately evade its obligations and frustrate the entire peace process

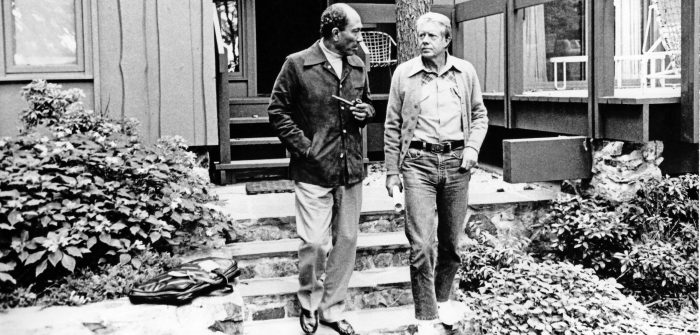

Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat and U.S. President Jimmy Carter leave Dogwood Lodge for a walk on the grounds of Camp David, Sept. 13, 1978. White House/CNP/ZUMAPRESS

Camp David was a watershed moment in Middle East diplomacy. It brought an end to nearly thirty years of hostilities between Egypt and Israel and led to the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the Egyptian territories captured in the 1967 Six-Day War—the first instance in which Israel withdrew from Arab territory occupied in that conflict. However, a separate peace with Egypt came at the expense of the negotiations’ larger goal: that of establishing a framework for peace in the Middle East in accordance with the 1967 Security Council Resolution 242 and commencing a process to resolve the question of Palestine.

Today, the Palestinians are still without a state and Israel continues its policy of occupation unabated. The ambiguity surrounding the agreement at Camp David generated confusion and disagreement over how to interpret its various provisions, leading to delays and, ultimately, dooming its full implementation. Without clear and coherent provisions on the critical issues at the core of the Arab–Israeli conflict such as self-determination, the withdrawal of Israel from Palestinian territories, and a mechanism to ensure that the obligations delineated in the agreement were upheld, the progress and promises made at Camp David remained unfulfilled.

In 1978, I joined the Egyptian delegation at Camp David as director of the legal department at the Egyptian Foreign Ministry. I was entrusted with ensuring that the outcome of the summit met the rules of international law and corresponded with Egypt’s legal obligations. I had raised some serious objections and reservations about the substance of both documents produced at Camp David. The negotiation process was contentious and, at times, appeared on the verge of collapse to the extent that throughout the almost two-week period, the Egyptian and Israeli delegations did not meet face to face. Instead, work was conducted bilaterally in separate meetings with the U.S. delegation.

Only in the last few days did President Jimmy Carter hold direct trilateral meetings with President Anwar Sadat and Prime Minister Menachem Begin. These meetings were held to present us with two texts drafted by the U.S. delegation comprised of two essentially separate documents: “A Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel” and “A Framework for Peace in the Middle East.” The first document provided the basis for what would become a formal peace treaty, the Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty, signed on March 26, 1979. Under the terms of this treaty, President Sadat achieved his goal of an Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula. In return, Egypt granted safe passage to Israeli ships through the Suez Canal, and both parties agreed to establish normal diplomatic relations.

Although President Sadat was hailed as a peacemaker by many in the West, the reaction in the Arab World was searing. There were vocal protests against what was perceived as an abandonment of the Palestinian right to self-determination and the perpetuation of the Israeli occupation. This discord extended to and reverberated within the corridors of the Egyptian Foreign Ministry with Foreign Minister Mohamed Ibrahim Kamel resigning at Camp David in protest (although his resignation was announced at a later date) and the Egyptian delegation, including myself, boycotting the signing ceremony at the White House.

At Camp David, the Egyptian delegation had concluded that the agreement did not sufficiently achieve two pillars which formed the basis for peace in the region, namely the restitution of all the territories occupied in the military conflict and the realization of the right of the Palestinians to self-determination, which was the Palestine Liberation Organization’s demand at the time. The delegation had serious concerns regarding the text’s ambiguity on the issue of Israel’s withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula. Although the draft called for the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Sinai, no reference was made to the status of the settlements. Egypt insisted on the withdrawal of all the Israeli settlements in Sinai which was only later accepted by Israel. Thus, the Egyptian delegation considered the draft of this section of the text unacceptable.

I conveyed these points of contention first to the foreign minister, who agreed with me, and then to President Sadat. After reflection, Sadat said, in English, “You are not a statesman,” to which I replied, in English, “Mr. President, I am here as a technician.” He pondered for a few minutes and then said in Arabic, “All of you in the Foreign Ministry do not understand me. You look at the trees while I look at the whole forest.” He continued, “I have listened carefully to what you have said and I do not accept your advice, particularly as I have assurances from President Carter.” President Sadat did not specify what assurances those were. I asked President Carter when he visited Egypt a few years ago and he replied that he conveyed assurances from Prime Minister Begin.

Similar to the Egypt–Israel framework, the document addressing Palestine, “A Framework for Peace in the Middle East,” contained specific flaws that rendered it inadequate and unacceptable. Camp David did break the negotiation deadlock and established a process for future negotiations; however, it either included ambiguous or insufficient provisions related to the aforementioned pillars of peace, Palestinian self-determination and the withdrawal of Israeli forces, or ignored critical issues, such as the status of Jerusalem. If judged solely on the merit of its textual content, the accord falls short of the requirements of a permanent peace settlement as defined in the relevant United Nations resolutions, specifically UN Security Council Resolution 242 (1967) and 338 (1973). These shortcomings did little to bridge the gap between the parties and helped to erode trust as future peace negotiations repeatedly continued to fail. Further, the absence of Palestinian representation during the initial negotiation process rendered the section of the accords on Palestine and Palestinian rights inadequate. Egypt, as a third party, could not accept less than what the Palestinians would accept.

It was indeed a positive step that both parties agreed that the final status of Gaza and the West Bank should be based on all the provisions and principles of UN Security Council Resolution 242, which entailed withdrawal from Gaza and the West Bank and recognition of the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people. However, the Camp David document failed to mention “withdrawal” (only alluding to it indirectly) or reference the nature and extent of the withdrawal of Israeli Armed Forces, or specify a date for the completion of the process. Instead, the text only emphasized future peace and normalization between the parties, essentially putting the cart before the horse. By not establishing the parameters for the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the territories they had occupied or fixing a date for withdrawal, the agreement failed to uphold the basic principle of withdrawal from the Occupied Territories as enshrined in Resolution 242.

For the second point, the draft did not make direct reference to self- determination, despite consensus that the final status negotiations must “recognize the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people and their just requirements.” The document laid out a framework for peace that consisted of a transitional period of no more than five years and the election of a Palestinian “self-governing authority” before the start of final status negotiations. The document’s provision to establish a self-governing authority for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza is made in lieu of an explicit reference to self- determination. The essence of the agreed formula was the transfer of authority from the Israeli military to the Palestinians. Yet, as articulated within the document, Palestinian “autonomy” was to be superficial at best. The governing authority’s powers and limits would be determined by Egypt, Israel, and Jordan—with Israel maintaining sovereignty over security. Further, Palestinians were not set to negotiate on their own behalf until the beginning of the final status talks—although, Egypt and Jordan could choose to include them in their delegations during the transitional periods.

For the second point, the draft did not make direct reference to self- determination, despite consensus that the final status negotiations must “recognize the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people and their just requirements.” The document laid out a framework for peace that consisted of a transitional period of no more than five years and the election of a Palestinian “self-governing authority” before the start of final status negotiations. The document’s provision to establish a self-governing authority for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza is made in lieu of an explicit reference to self- determination. The essence of the agreed formula was the transfer of authority from the Israeli military to the Palestinians. Yet, as articulated within the document, Palestinian “autonomy” was to be superficial at best. The governing authority’s powers and limits would be determined by Egypt, Israel, and Jordan—with Israel maintaining sovereignty over security. Further, Palestinians were not set to negotiate on their own behalf until the beginning of the final status talks—although, Egypt and Jordan could choose to include them in their delegations during the transitional periods.

These stipulations on the nature of the Palestinian self-governing authority and Israel’s continued sovereignty over security effectively rendered the promise of “autonomy” meaningless by abandoning the Palestinians’ right to self-determination. It is inconceivable that an agreement to confirm the application of Resolution 242 could be misconstrued and read as limitations on the exercise of the most fundamental and sacred of these rights: the right to self-determination. In point of fact, no amount of verbal distortion could misinterpret such clear-cut and unqualified UN commitments. The exercise of the right to self-determination is the only logical conclusion that can be derived from the binding commitments arrived at through Camp David.

The nature of the agreement reflects the balance of power among the parties at Camp David and the Palestinians, who were not present. The U.S. delegation failed or refused to apply necessary pressure on Israel to level the playing field and elicit breakthrough concessions. As such, much of the document was drafted according to Israeli priorities. The Israeli delegation succeeded in shifting the focus of the talks from achieving a comprehensive conflict-ending peace to a more modest “framework” agreement, which laid out the broad outlines of a U.S.-led peace process while leaving the details of the actual treaty to be worked out later following a transitional period. The Camp David Accords did not outline the endgame or the core issues of the conflict such as land, Jerusalem, and withdrawal from the West Bank.

While some issues were addressed, the ones that were more problematic for Israel were left vague or excluded. For instance, the future of the city of Jerusalem was notably and intentionally left out of the agreement. Although President Carter exchanged letters with both President Sadat and Prime Minister Begin prior to the summit on the issue of Jerusalem, any commitments they made did not appear in the final agreement. This was due, in part, to Israeli objections on the topic during the summit. The document’s failure to address these issues and its non-binding nature only highlighted the gaps between the parties while denying them of any stake in the agreement. For an agreement to be credible, it must not only mention these core issues but actually identify how each is to be resolved.

Israel, then, capitalized on the ambiguity of the agreement and the absence of a binding process to obstruct and prolong its implementation. The Israelis seized upon the concept of a transitional period agreed to at Camp David to postpone the hard decisions over issues such as borders and security. This enabled Israel to evade its obligations under the accord and frustrate the broader peace process. These efforts proved so successful that, just a little over a year after Camp David, a November 16, 1979 article in the New York Times stated, “Israel is turning the offer of ‘autonomy’ to Palestinian Arabs into a sham . . . . They are provoking even moderate West Bank leaders into hostility and binding them to the Palestinian Liberation Organization. How the Israelis expect to negotiate with people they seem determined to humiliate is almost beyond understanding.” Moreover, while Camp David broke the negotiation deadlock, because of the contentious atmosphere of the summit, it shifted priorities and rewrote agendas so that an agreement might be obtained between parties, regardless of whether it actually brought the parties closer to a settlement. The geopolitical context in the years following the signing of Camp David and the continued relegation of Palestinian rights to the sidelines made it difficult to extract the necessary concessions that can work toward a comprehensive and permanent peace settlement.

Camp David’s Aftermath

The successful conclusion of the Egypt–Israel peace treaty represented the high-water mark for the peace process during the Carter administration and in the years to come. Following the summit, U.S. attention waned amid volatile regional developments, including upheaval in Iran and the outbreak of war in Afghanistan. The continued absence of meaningful support for the framework, both from Palestinians and other countries in the region, complicated the continuation of the peace process laid out in the agreement. Amid these challenges that worked to constrain the progress toward peace, the United States seemed to place greater value on process over substance, similar to what had occurred at Camp David.

While at times there seemed to be occasional glimmers of hope for peace, as seen with the initial optimism surrounding the Oslo Accords, Israel consistently endeavored to frustrate and prolong the peace process. When in power, whether under Rabin, Peres, Barak, or Olmert, the Labor government expressed a willingness to compromise. However, these assertions were merely rhetorical and no concerted action was ever taken to work toward genuine peace. In over fifteen years of negotiations, I witnessed various Israeli delegations impede efforts to reach a comprehensive peace settlement. Often, this was achieved through strategically stalling and prolonging the negotiation process to delay implementing their obligations and alter facts on the ground in their favor.

A master at this strategy, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has steadily allowed the expansion of settlements in the West Bank and implemented laws discriminating against non-Jews. In contrast to the steps the United States took at Camp David to establish itself as a major player in the peace process, Washington under the Donald Trump administration has seen whatever credibility it might have had as a mediator severely damaged. The current administration’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and its demand to liquidate the United Nations Relief and Works Agency or UNRWA reflect a more blatant bias toward Israel that is counter-productive to peace. Moreover, such actions violate numerous Security Council resolutions and are prohibited under international law. The continued absence of progress toward a comprehensive resolution of the conflict will only harden Israeli and Palestinian antipathy and distrust toward each other.

A New Approach to Peacemaking

Although President Carter’s ambitious goals for Camp David went unmet, the summit was nonetheless a pivotal moment in the history of the Arab–Israeli conflict. If the provisions of the accord had been faithfully developed in the years following Camp David, Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank could have reaped immediate benefits: the Israeli military occupation would have been terminated and Palestinian rights would have been recognized, as defined by the agreement’s reference to UN Resolutions 242 and 338. Instead, decades after the transitional period and final status negotiations outlined in the Camp David framework were to have occurred, no Palestinian state has been established and the burdens of Israeli occupation increase every day. This serves as a useful reminder that the seeds of these issues were planted at Camp David.

At present and in light of Israel’s policy of obstructionism and the Trump administration’s obvious bias, the Camp David Accords represent an echo of the past, rather than a model for future peace. Stalled negotiations present an opportunity to rethink a deeply flawed and outdated approach to Arab–Israeli peacemaking. Perhaps it is time to abandon the U.S.-led peace process that Camp David set up in favor of a more proactive approach and a process that is binding, continuous, and anchored in justice and the rule of law. If a just peace settlement is to be achieved, one that realizes the right of Palestinians to live in an independent Palestine, it will require a comprehensive agreement that outlines a detailed picture of the endgame and tackles the hard decisions that Camp David neglected to address.

Nabil Elaraby is an Egyptian diplomat and lawyer. He served as Secretary General of the League of Arab States from 2011–16. Prior to his appointment as Egyptian Minister of Foreign Affairs in March 2011, he served as Egypt’s permanent representative to the United Nations in both New York and Geneva and participated in several peace talks, notably the Camp David Middle East Peace Conference and the Taba dispute arbitration. Previously, he was a judge at the International Court of Justice.

Read More