Scramble for Syria

Iran’s support for the Al-Assad regime in Damascus has long provided it with a foothold in Lebanon, Palestine, and the rest of the region. But with its deepening role in the Syrian civil war, Tehran is losing hearts and minds in the Arab World.

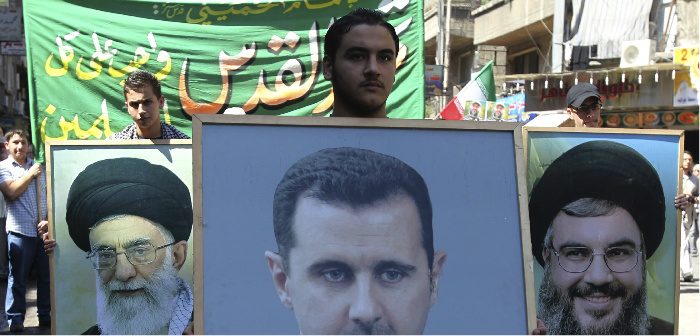

Demonstration at Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp, Damascus, Sept. 3, 2010. Khaled Al-Hariri/Reuters

Since the outbreak of protests against the Syrian regime in 2011, Iran has been a leading force in the Syrian civil war in support of President Bashar Al-Assad. Alongside its military interventions in crucial battles like the fall of Aleppo in December last year, Iran has grown its economic, political, and ideological influence within Syria.

Iran’s leaders are keen to protect their key ally in the Middle East. They consider the stability of Al-Assad’s regime vital for Iran’s own security, and for the projection of Iran’s power in the region. Tehran’s privileged relationship with Damascus has facilitated its support for the Shiite Hezbollah group in Lebanon, and for Hamas and other Palestinian factions. The constellation of allies, which Tehran calls the “axis of resistance,” or the “front of refusal,” has given Iran strategic depth in the heart of the Arab World, spread its influence across the eastern Mediterranean, and widened its room for maneuver and dissuasion in Iran’s confrontation with the Israel and the United States. Iran’s support of resistance groups has won limited support in Arab public opinion, although that has been mostly squandered by Iran’s decision to support Al-Assad come hell or high water.

Iran’s involvement has helped Al-Assad’s beleaguered regime survive a popular revolt and intense international pressures, enabling it to muster further political and diplomatic support as well as economic and military aid. Until the launching of Russia’s air operations against Al-Assad’s opponents in September 2015, Iran was the Syrian leader’s most active backer in the war effort. Iranian support began during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s second term as Iran’s president. It has continued, without fail, since Hassan Rouhani’s election as president in 2013.

Iran has been very active on all fronts. Major General Qassem Soleimani, chief of the Quds Force—the extraterritorial branch of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—has been spotted at different locations on major battlefields in Syria with pro-regime fighters and Shiite militias. The “shadow commander” is said to have a significant influence in shaping the pro-regime military campaign. The Quds Force could therefore be involved in the last operations carried out by the pro-Al-Assad forces in the Raqqa and Deir Ez-Zor regions.

Iran deepened its involvement in the Syrian conflict despite the additional stresses on an Iranian economy already weakened by international sanctions, and the international opening Tehran achieved in 2015 through the nuclear accord reached with Washington. Underscoring the importance of Al-Assad’s survival to Iran’s leaders, Tehran has publicly acknowledged the deaths of at least one thousand Iranian combatants in the Syrian conflict, including 486 members of the IRGC.

Iran has leveraged its involvement in the war to significantly reinforce its influence on the Syrian regime, which has long been sensitive about sacrificing independence in the close relations with Tehran. Iran is working toward establishing permanent influence and protecting its long-term interests, whatever the outcome of the war may be, as part of Tehran’s strategy to reinforce its “axis of resistance.”

Iran’s deployment of thousands of military and security personnel is giving the Iranian army, as well as the Quds Force, the Basij, and other units within the IRGC, valuable experience. Iranian forces have improved their operational capacity in fighting a semi-conventional war, and sharpened Tehran’s ability to intervene in other regional conflicts.

The Islamic Republic supported the deployment of non-state forces to Syria, such as the Lebanese Hezbollah group and Shiite volunteer forces drawn from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. It has backed the creation of the National Defense Force, a multiconfessional militia numbering in the thousands. These forces have contributed heavily alongside Iranian forces to the Al-Assad regime’s military successes, and could be used to secure Iran’s future interests in Syria and the broader Levant against outside powers—including Russia—regardless of the outcome of the Syrian conflict.

In cooperation with Hezbollah, the Iranian regime has worked since 2012 to reinforce the demographic weight of Shiites in the Syrian capital. Iran has supported the resettlement of Shiite militants and their families especially in the quarter surrounding the Shiite shrine of Sayeda Zeinab in the southern suburbs of Damascus. Iran has sought to fundamentally change the demographic makeup of other regions of the country—notably the zones linking Damascus and other important cities, like Homs, with the Lebanese border—by encouraging the departure of Sunnis and their replacement with Shiites coming from other parts of Syria, as well as, it would seem, Lebanon and Iraq.

Likewise under the cover of propping up the Al-Assad regime, Iran’s interference in the Syrian economy has rapidly grown. Since 2011, Tehran has opened an estimated $6–10 billion line of credit, while local sources cite a $5.4 billion current debt owed by Al-Assad’s government. In January 2017, five protocols were signed on the occasion of the Syrian prime minister’s visit to the Iranian capital, including a mobile network operator license for a company largely run by the IRGC, and a contract for the mining of phosphate in Sharqiya. The Syrian regime allocated Iran some five thousand hectares for agricultural development, and one thousand hectares for the construction of oil and gas terminals, as well as hydrocarbon storage. An accord was signed for the provision of land for animal husbandry. Tehran obtained the right to invest in Syrian ports and, according to a declaration by the Syrian prime minister, in the “reconstruction of Syria,” which would leave the door open to other lucrative contracts in the future.

Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, has said that Tehran treats Syria, increasingly, as “one of its own provinces.” Iran believes that, having saved Al-Assad, it can now help itself to Syria’s economy. The Syrian opposition has denounced such developments as “the pillage” of the country’s wealth by “extremist Iranian militants.” Yet given the current isolation of the Al-Assad regime within the Middle East, such economic penetration could give Tehran pride of place in the country’s reconstruction and help bolster its influence for the foreseeable future. Tehran has attempted to push bilateral commercial relations. Trade between the countries has increased since 2011, but Tehran, as of 2015, still ranked only fourth among Syria’s trade partners, far behind Iraq, which ranked first, and—more surprisingly—Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Iranian activities in Syria are not limited to the political, military, and economic domains. Tehran, which has for years developed its cultural diplomacy in Syria, employs soft power to consolidate influence. In February 2017, many Syrian cities officially celebrated the thirty-eighth anniversary of the Islamic Revolution to show the country’s solidarity with Iran. The Iranian cultural center in Damascus, in collaboration with the Iran-Palestine Association, jointly organized an event for the occasion, called the “38th Anniversary of the Iranian Islamic Revolution’s Support for Palestine and Anti-Zionism.” The initiative aimed to improve Tehran’s image in public opinion by turning attention away from its activities in Syria toward its role in the Palestinian cause and criticizing Israel.

All of these activities are clearly aimed at reinforcing Tehran’s ideological pull. Iranian charitable foundations, like the Imam Khomeini Relief Committee, are active in Syria and Lebanon, and offer financial and material support to groups that display favor to Tehran. Religious tourism is among the activities encouraged and supported by Iranian authorities to deepen the cultural links between Syria and Iran. Every year, hundreds of thousands of Iranian pilgrims come to Syria to visit the shrines of Shiite saints—the tomb of Zeinab, the daughter of Ali, the first Shiite Imam, being the holiest such site in Syria. Within a month of the partial truce in Syria in December 2016, Tehran and Damascus began discussions on how to develop further religious tourism and the infrastructure needed to welcome Iranian visitors.

The civil war in Syria has also given Tehran a theater for its cold war with Saudi Arabia, its most important rival in the region. Saudi Arabia and Iran, almost without exception, have found themselves on opposite sides of the wars that emerged out of the U.S.-led 2003 invasion of Iraq and, later, the 2011 Arab uprisings. Both have exploited the increasingly sectarian tone of conflicts across the Arab World to their advantage; Tehran has often found a foothold in Arab countries with significant Shiite populations, like Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria, while Riyadh has consistently claimed the mantle of leading the orthodox Sunni world. The cold war includes proxy campaigns in Iraq and Yemen, but Syria is the critical battlefield given its strategic position in the heart of a Sunni-majority region that includes not only Syria itself but Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Israel. The fall of Aleppo to Al-Assad’s forces in December 2016 gave Tehran an edge in the balance of power with Riyadh, no doubt explaining why Iran refused to accept Saudi participation in peace talks held in Kazakhstan’s capital, Astana.

Arabs and Persians

Tehran has every reason to believe that its moment in Syria has arrived. Al-Assad’s military position appears more secure in Damascus and Syria’s heartland, while opposition forces seem weakened and divided, pushed back toward the country’s peripheries. On the battlefield, Iran’s Shiite allies are forces to be reckoned with—Hezbollah more so than ever, as the organization has gained more field experience and the ability to play an important role in future regional conflicts. Diplomatically, Tehran, in collaboration with Moscow and Ankara, has marginalized not only Riyadh and the other Gulf monarchies, but Washington and the Western bloc in negotiating a settlement in Syria.

Yet, it remains to be seen whether Iran has really secured lasting influence in Syria. Despite its heavy investments and sacrifices, has Iran truly become Syria’s long-term “friend” and “protector”? Such a conclusion would be naive and amount to a fundamental misunderstanding of the regional and international reality. Above all, uncertainty characterizes the current situation facing Iran and other actors involved in the Syrian conflict.

The civil war is far from over, despite the gains made by Al-Assad and his allies. No compromise or settlement between the Syrian regime and the opposition present at the Astana conference can be foreseen so far; it is difficult to predict what parts of Syria that Al-Assad and his allies can ultimately control. Iran, Russia, and Turkey, moreover, do not share identical points of view nor interests in Syria, nor agreement on future conduct of the war. Changes in the situation on the ground may depend heavily on how Russian–American relations evolve under President Donald Trump, who has suggested he could cooperate with President Vladimir Putin in Syria, a possibility which seems to interest Moscow. A general rapprochement between the two countries could occur, ideally from Putin’s viewpoint without undercutting Russia’s deepening strategic relations with Iran. Either way, a Russian–American entente over Syria is an alarming possibility for Tehran, especially given its rising tensions with the United States since Trump’s election in 2016.

There are numerous outstanding questions about Iran’s regional thinking. Will Tehran pursue an expansionist policy, leaning for the most part on Shiite confessional currents, contrary to the initial, ecumenical ambitions of the Iranian revolution in 1979 to unite all branches of Islam? Will Iran continue to concentrate on the Arab World, whereas its geopolitical position should lead it toward a more multidirectional policy, allowing it to benefit fully from its exceptionally advantageous geographical location? Is Tehran even fully conscious that its current interference in Arab affairs is being met with increasing hostility and could turn against Iran with real effects?

Already, unfavorable opinion toward Iran has increased considerably since 2012 across the Middle East. According to several polls conducted at the end of 2016, including in Iraq and Lebanon, a majority of those asked held a negative opinion of Tehran. The degradation of Iran’s image across the Arab World will only increase if it continues to pursue its current policies in Syria—it could even push Arab countries, generally divided and unable to cooperate effectively, to counterbalance and actively oppose Iran. This is already happening to a certain extent, with Saudi efforts—with the Trump administration’s blessings—to give its “Islamic Military Alliance” an anti-Iranian tone. Whatever Iran does in this part of the world, its policies face an insurmountable obstacle: Iran is Persia, which will always be suspect in Arab lands. The Islamic Republic’s leaders may do well to understand this reality.

Translated from the French by Amir-Hussein Radjy.

Mohammad-Reza Djalili is Emeritus Professor of International History at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies (Geneva). He previously taught at the Université Panthéon-Assas (Paris II) and at the University of Tehran.

Thierry Kellner is a lecturer at Université libre de Bruxelles and associate researcher for the Group for Research and Information on Peace and Security. He is the author of L’Occident de la Chine: Pékin et la nouvelle Asie centrale (1991–2001).