Syria: The Illusive Settlement Part 2

Resolving the Syrian conflict offers an opportunity to bring stability to the Middle East, but only if compromises can be made, starting with UN resolution 2254.

Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a meeting with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia, September 13, 2021. Sputnik/Mikhail Klimentyev/Kremlin via REUTERS

In Part 1 we focused on the domestic drivers of the Syrian conflict. We also discussed the background of the various foreign military interventions and the motivations prompting external players to intervene militarily in Syria, thereby transforming it into a full-fledged conflict and a proxy war among regional and international rivals.

In this part we will explore how to generate an internal dynamic able to create a domestic critical mass in support of orderly change in Syria as well as an external dynamic able to tackle the issue of foreign military interventions. The interaction between these two dynamics should enhance the prospects of reaching a political settlement.

As the United States has repeatedly stated, regime change in Damascus is no longer on the table. The issue, rather, is Syria’s domestic and foreign policies. In other words, if the behavior of the government in Damascus changes there is a possibility of reaching a political accommodation. Ultimately, the Syrian people should decide the kind of regime they wish to live under through free and fair elections meticulously prepared according to the highest international standards of transparency and accountability as called for in UN resolution 2254.

UN Security Council resolution 2254 contains a road map for a political settlement which includes new governance arrangements, constitutional reform, and elections held under UN supervision. These would take place in an enabling environment which would include efforts to combat terrorism, release prisoners and abductees, return refugees, provide humanitarian aid to all Syrians, and assist reconstruction.

In anticipation of such elections, the focus should be on how to bring about the requisite change in the behavior of Damascus. Towards this end, a number of considerations pertaining to the internal situation in Syria need to be taken into account.

The Unsustainable Present Situation

One such consideration—sanctions—has not been effective in regime change nor in substantively modifying behavior. History is replete with examples, but the most relevant is close to home: Iraq under Saddam Hussein. In that case they were UN Security Council Sanctions; in the case of Syria, there were no such sanctions. While the U.S. and EU sanctions have had a considerable impact on Syria, the most harmful effects have been felt by the hapless population, not the political elite. Just as Saddam Hussein was able to manipulate the Oil-for-Food Programme—whereby Iraq was allowed to sell oil to buy food under a scheme approved by the United Nations Security Council—Damascus, facing fewer restrictions and possessing allies willing to help, has been able to maneuver in the grey areas of international trade. There is no doubt that the crisis in Lebanon has impaired Damascus’ ability to deal with an already difficult situation, but one should not underestimate the creativity of the Syrians. They have survived partition, foreign occupation, famine, boycotts, civil strife, and wars over many centuries, always adapting but determined to safeguard the multi-ethnic and multi-religious character of Syria.

Moreover, despite waves of migration throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Syrians are strongly attached to their country. They want a better future for themselves and their children. After ten years of internal strife, the vast majority of Syrians have now reached the conclusion that the continuation of the present situation is not only unsustainable, but could very much be the end of Syria as a nation state. Their homeland would be no more.

Obstacles to UN Resolution 2254

In spite of UN efforts, there has been scant progress in implementing resolution 2254. This is not surprising given the regional rivalries, disagreement among the permanent members of the UN Security Council, the unrealistic positions adopted by the Syrian opposition, and the reticence of the government in Damascus as outlined in Part 1. There was also no serious effort to directly address the following three issues that will ultimately determine the settlement. First, the specific political reforms required for the full implementation of resolution 2254 and how they can be linked to reconstruction. Second, the need to agree on what constitutes “political transition”, given that regime change is no longer an option. Third, the matter of foreign military interventions—Israeli, Iranian, Turkish, Russian, or U.S./NATO—in Syria must be addressed.

Since 2019, I have argued that the best way to bring about a settlement in Syria, and at the same time check and reverse Iranian and Turkish interventions in the region, is an Arab initiative on Syria based on implementing UN Security Council resolution 2254 in a package deal enacted on a step-by-step basis. This process would link the reconstruction and reintegration of Syria into the Arab and international community with concrete steps to be taken by Damascus in the implementation of the resolution.

Needless to say, this process needs to be carefully calibrated in a manner that incentivizes the government in Damascus to cooperate in the full implementation of resolution 2254. A phased and incremental approach toward reconstruction based on positive incentives—the progressive lifting of sanctions, a gradual normalization of relations, and a staggered disbursement of reconstruction funds—is crucial. In return, the government would undertake specific economic and political reforms (Article in Al Sharq Al Awsat, December 19, 2019).

The range of activities that comprise the progression from stabilization, recovery, and rehabilitation to reconstruction should be carefully calibrated with political and economic reforms in Syria. An innovative local, bottom-up funding approach was proposed by Omar Abelazziz Hallaj in a recent paper published by the Geneva Center for Security Studies, whereby aid mechanisms would focus on gradually formalizing local governance as a means to distribute services. Such a package is best presented by the UN while backed by the prospective major donors, especially the Arab Gulf and the European Union, who stand to lose the most from an unstable Syria. The purpose of such an initiative for a political settlement should be to create an internal dynamic that produces a critical mass in support of orderly change in Syria. This is only possible if the process is inclusive, encompassing the elements of Syrian society that are committed to a non-sectarian national state.

Syrians are divided on the nature and pace of reforms as well as on the fate of the regime. While some are unable to accept a regime that, in their view, is solely responsible for the tragic fate that has befallen Syria, others, particularly the Alawites, remain convinced that the present regime is their sole guarantee against acts of revenge. The Alawites and others who have benefited from the regime will require iron-clad guarantees concerning their safety and security.

Throughout this process, the special nature of Syria must be taken into consideration. It has always been a country of diverse religious and ethnic groups. Yet more than any other country in the region, these groups have been able to live together in relative harmony. It is the culmination of centuries of historical developments. While the conflict has undoubtedly left deep scars on every Syrian, the history and tolerant culture of the society will help in the healing process. Even the Kurds, who make up 10 percent of the population, do not seek an independent state. They aspire to express their Kurdish identity and culture within a unified Syrian state. They understand that this is the best way to preserve their identity or otherwise face Turkish domination.

Additionally, no one has been able to rule Syria, regardless of the ideological orientation of the regime, without the support of the merchant class in the major cities, particularly Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, and Latakia. This economic class, which maintains deep historical relations with Arab countries, has been marginalized during the war and is waiting for the opportunity to resume its traditional position in Syrian society. Conversely, the new business elite created by the conflict has shallow roots in society.

President Assad has repeatedly declared that one cannot turn the clock back on Syria, implying he is open to change. However, what kind of change, and at what pace, is the question. A question that can only be answered when Damascus is continually put to the test.

Dissecting Foreign Intervention in Syria

In the first part we discussed the background of the foreign military interventions that together define the external context of the Syrian conflict. We now need to dissect the nature of each of these interventions so we may be able to determine how to best deal with each one.

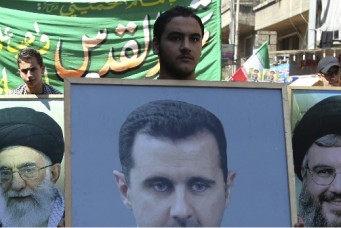

The multiple foreign military interventions take different forms. The most concerning and destabilizing are those led by Israel, Iran, and Turkey. However, Iranian intervention captures the most attention because of its strategic implications and its impingement on the interests of the greatest number of parties—not only the Gulf Arabs, Europeans, and Israelis but also Russia and the United States. It is also the most complicated to manage.

The Syrian-Iranian Relationship

In order to appreciate the hurdles involved in dealing with the Iranian presence in Syria, one needs to unpack the Syrian-Iranian relationship, cultivated decades ago by the late President Hafez Assad as a counterweight to his Ba’ath rivals in Baghdad. In other words, its genesis as well as its underlying motivation was political not ideological.

Iran has no natural constituency in Syria. In Lebanon, for example, it has an ideological and religious kin in Hezbollah. Whereas the Alawites, who have dominated the ruling elite in Syria since 1970 and are considered an off-shoot of Shiism, are actually amongst the most secular segments of Syrian society. Their attachment to Iran is not based on ideological or religious affinity but rather on political expediency. In short, it is a tactical alliance.

Moreover, the increasing influence of Iran in Syria—and for that matter the region—did not result from deliberate calculations by Tehran, but rather as the result of three events. First, the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 without adequate preparation for the days after and, therefore, effectively handed the country to Iran on a silver platter. Second, Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated in 2005 resulting in the subsequent withdrawal of the Syrian army and the beginning of the process by which Saudi Arabia aimed to ostracize Damascus, creating a political vacuum that Tehran quickly filled. Third, the conflict in Syria, which started in 2011, resulted in Damascus’ increased dependence on Tehran, not only militarily but also economically. It is worth noting that it was not until the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the downfall of the Saddam Hussein regime that Tehran was able to make serious inroads in the region. The sole exception was the case of Bahrain where there is a Shiite majority, and yet Tehran remains unable to install a friendly regime.

Ironically, one of the unintended consequences of the Syrian withdrawal from Lebanon was increased Iranian influence in Damascus. During Syria’s presence in Lebanon, Damascus exercised considerable control over Hezbollah. Once removed, Iran was able to exercise unchallenged direct influence over Hezbollah. The nature of the triangular relationship shifted in favor of both Hezbollah and Tehran. Instead of Damascus playing the role of the influential power broker, it was caught between an ascendant Hezbollah and its patron in Tehran. It has always been in Syria’s national interest to act as the balancing factor in Lebanon’s confessional political system. However, that does not necessarily fully coincide with the interests of either Tehran or Hezbollah.

Iranian influence in Syria also increased as the result of sanctions imposed by the United States and the EU. This created an economic dependency on Iran, supported by a new business elite which did not exist before the conflict.

In addition, Iran managed to enhance its influence in Syria by exploiting the vacuum created by the Arab retreat in 2012. This was possible through providing military and economic assistance to the government, investing in the economy, establishing a small network of businessmen, and nourishing members in the security services who cooperated with Iran for tactical reasons. Iran’s influence in the Syrian army is checked by Russia.

Iran has also been able to make inroads into Syrian society through proselytizing its brand of Shiism, buying properties, and establishing religious schools. This has been particularly effective amongst the most economically vulnerable groups. If such vulnerabilities can be addressed, this process can be reversed.

Last but not least, despite Iran’s increasing presence and influence prior to 2011, Gulf countries had an important economic interest in Syria, and they still see the economic opportunities that a stable Syria can offer. There is also a significant Syrian diaspora in the Gulf that continues to maintain close familial and economic ties with their home country.

Israel

On the other hand, the military actions taken by Israel since 2011 can be viewed as a reaction to the expanded Iranian military presence. Therefore, it can be assumed that once a formula is found to address Iran’s enhanced presence, the Syrian-Israeli situation could very well revert to the one that existed between the 1974 Disengagement agreement and 2011, when the Syrian-Israeli front was largely calm. While reverting to such a situation does not resolve the matter of occupied territories, and therefore cannot be a not a long-term solution, it will assist in creating better conditions for establishing a regional security system.

United States

The small U.S. military presence was never going to be permanent. Once a political settlement is found, it is expected that the United States will remove the little assets it has on the ground. This will likely take place in the context of a wider regional arrangement involving Damascus, Tehran, Ankara, and Moscow and would be in line with the U.S. strategy to reduce its military presence and commitments in the region. Given the recent developments in Afghanistan, the United States may now be more eager to find an arrangement that would expedite its departure.

Russia

Russia is different. Now that Moscow has fulfilled its centuries-long dream of establishing a military presence in the warm waters of the Mediterranean, it is not expected to pack up and leave. After all, its presence is at the request of the Syrian government. Neither the present government, nor any future one, will be in a position to request Russia’s departure. Meanwhile, it appears neither Washington, Tel Aviv, nor for that matter, the Arabs have major problems with the Russians remaining in Syria, if only to check Iranian influence.

Turkey and Iran

Iranian and Turkish presence and influence are the most pressing issues. Three conclusions come to mind. First, although Iranian influence in Syria is evident, it is also exaggerated. There is a lack of popular empathy for Iran that is not confined to the general population; it has resonance elsewhere. In addition to this, Iranian influence is also kept in check by Russia. Second, the Iranian-Syrian relationship took some forty years to reach its current point. The challenge is to bring it back to where it was in 2011. Once this is accomplished, matters should be able to take care of themselves. Third, although Turkey’s presence is of a much shorter duration than Iran’s, it has long-term implications for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Syria. Unlike Tehran, which largely depends on the Syrian government to spread its influence, Ankara, with the help of local proxies, exercises political and administrative control over the territories in which it maintains a military presence.

What is clear, however, is that the longer the present situation prevails, the more entrenched both Iran and Turkey will become in Syria. And as a consequence, Iranian and Turkish encroachment in Iraq will be more difficult to address.

Iran’s and Turkey’s regional behaviors will remain a matter of concern until threats to the territorial integrity of both Syria and Iraq are comprehensively and effectively addressed. Once this is achieved, any threats to other countries in the region will be reduced to a manageable level.

Regional Security System

Ultimately, the best way to address the security concerns of the Middle Eastern countries is an agreement to establish a regional security system where all sides can balance their interests and security concerns. In this regard, a revived Iranian nuclear deal (JCPOA) may be the first concrete step.

Long-term

Agreement means different things for each party involved. For the Arabs, Iran and Turkey must cease intervention in their domestic affairs, and Iran can never possess nuclear weapons. Immediately, this introduces the concerns over Israeli nuclear capabilities. For Iran, regime change in Tehran, as a policy pursued by its foreign adversaries, must be discarded once and for all. Turkey would require an arrangement to secure its southern border.

The best means to arrive at such a result is through an Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)-inspired process, but one that takes into account the two basic differences between Europe and the Middle East. First, unlike Europe, there is an occupied people—the Palestinians—and occupied territories in the West Bank, Gaza, the Syrian Golan Heights, and the Shebaa farms in Lebanon. Second, there is a “non-declared” nuclear weapon state and another trying to acquire the capability to produce nuclear weapons.

Building a regional security architecture is a complex and time-consuming process. Ultimately, a zone free of weapons of mass destruction should be established. Until then, security in the Middle East will remain fragile. A well structured, step-by-step approach is required, with the clear objective of establishing a zone of security and cooperation free of weapons of mass destruction. In this context, a viable Palestinian state would be created in line with the two-state solution, and Israel would withdraw from the remaining occupied Arab territories.

Short- and medium-term

While establishing a regional security system is a long-term objective in ensuring the stability of the Middle East, dealing with the concerns surrounding both Iranian and Turkish behavior and the reform process in Syria should be short- and medium-term objectives that can be realized. Meanwhile, both Tehran and Ankara must be made to understand that any further encroachment—any destabilizing actions—on their part will come at a price.

Iran will need a combination of incentives and disincentives to concede its advantageous position in Syria. Tehran will likely consider the matter from a regional security perspective. Incentives are offered by a regional security arrangement: a revived JCPOA followed by regional dialogue on the security concerns of both Arabs and Iranians. A number of proposals are on the table—Arab, Iranian, Russian and American. The recognition of at least some of Iran’s economic interests would be another incentive. In the event of significant Arab reconstruction assistance and investments, Iran’s economic influence will be greatly reduced. As for disincentives, the internal dynamics of reconstruction and reform would erode its newly created constituencies that underpin its influence in Syria.

Ankara, after pursuing a policy of regime change in Damascus, has scaled back its ambitions in protecting itself against what it considers a Kurdish threat to its national security. Therefore, a mutually beneficial arrangement with the Syrian government can be achieved on the precedent of the 1998 Adana Agreement by which Syria expelled the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and Turkey was accorded the right of hot pursuit into Syrian territory. An updated Adana Agreement—given the infiltration of fighters from Turkey into Syria over the past ten years—should balance the security rights and obligations of both countries. This time around Syria will need guarantees to protect its northern border. This will require a dialogue between Ankara and Damascus possibly with the help of Russian mediation but preferably under U.S.-Russian auspices. President Erdogan has proven to be a pragmatist when it suits him. He has reversed course with Egypt and Saudi Arabia. He may well do the same with Damascus if it serves his interests. Unless Ankara is prepared to maintain a long-term presence in northern Syria—with its implied economic costs and international scorn—the only long-term and sustainable arrangement to secure Turkey’s southern border requires the cooperation of the government in Damascus. This is also probably the best arrangement for the Kurds in Syria to ensure their distinct identity within the Syrian state. Additionally, Ankara has extensive economic interests in the Arab world. It will have to understand that it cannot expand these interests if it continues to pursue its unrealistic Neo-Ottoman political ambitions.

In short, we need to move along two tracks to bring about a political settlement in Syria. First, a package of incentives and disincentives to entice Damascus to cooperate in the full implementation of resolution 2254 must be created. This would ultimately lead to free and fair elections, and in the process, peel away the constituencies that comprise Iran’s support network by establishing economic and financial dependency on Arab interests. Second, a process to reduce foreign interventions, primarily in Syria and subsequently in Iraq, must be initiated that would open the door to a regional security system.

Looking ahead

The prevailing argument amongst those who follow Syria is that the situation is extremely complicated, and therefore it does not, at this stage, lend itself to a political settlement. Therefore efforts should be confined to humanitarian assistance, in the hope that more propitious conditions will prevail in the future, for example, regime change. As a counter argument, I have long maintained the opposite. A settlement in Syria may well enhance the prospects of resolving other conflicts in the Middle East. Syria is the one conflict where most of the underlying causes behind the multiple conflicts intersect primarily: efficient and effective governance that meets the aspirations of the populations and foreign, regional, and international interventions and occupation.

As complicated as the situation may seem, one should not give up hope. Lately, after an extended period of stagnation, there have been indications that positive movement might be possible. The summit between presidents Biden and Putin may have, once again, opened the door to serious discussions on a Syrian settlement. Russia and the United States have, in the past under both the Obama and Trump administrations, held exploratory bilateral talks in this regard. Lately, on July 9, 2021, Washington and Moscow reached a compromise which made the adoption of resolution 2585 by the UN Security Council possible. This agreement on the delivery of cross-boundary humanitarian assistance is a further indication that both capitals are serious about re-engaging on a political settlement. The recent meeting in Geneva on September 13, between National Security Council (NSC) Middle East coordinator Brett McGurk and Russian Presidential Advisor Lavrentiev and Deputy Foreign Minister Vershinin appears to indicate an interest by both countries to resume discussions about Syria that have been taking place on and off since 2015.

Meanwhile the Biden administration, while yet to articulate a new policy on Syria, appears to be showing interest in exploring the prospects of finding political settlements to the conflicts that have for so long afflicted the Middle East. If anything, the debacle in Afghanistan should serve as an incentive for Washington to shore up its credibility in the region. It is not sufficient to dispatch the Secretaries of Defense and State to the region to express appreciation for the assistance it received in the withdrawal from Afghanistan. Washington needs to demonstrate, with action, that it appreciates the security concerns of not only the Gulf countries, but also Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq. This would entail serious engagement in resolving the festering conflicts in the region.

What happens in the Middle East does not stay in the region. In the mid-1970’s the United States sponsored a peace process between the Arabs and Israelis to prove that it was not a declining power after Vietnam.While it is true that the strategic priorities of the United States have since shifted, an unstable Middle East will impair Washington’s ability to concentrate its efforts on how to best deal with an ascendant China.

Moscow, on the other hand, has long been maneuvering to transform its military successes in Syria into political gains. It understands that this can only be achieved through an internationally sanctioned political settlement offered by resolution 2254. For that, it needs the active engagement of the United States.

This would not be the first instance Moscow and Washington cooperated on Syria. In 2012 they produced the Geneva Communique, even if they had different interpretations of the document, and in 2013, they were able to agree on the removal of chemical weapons. In 2016, they produced resolution 2254. In fact, between 2015 and 2017, the extensive contact between then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, as well as their respective militaries, held the promise of reaching an understanding that could have opened the door to a political settlement. Unfortunately, in the waning months of the Obama administration, Russian-American relations suffered a downward spiral. The U.S. air force attacked the Syrian Army in September 2016, which the United States admitted was a mistake. A few days later, a humanitarian convoy was attacked in Aleppo province. As is expected in such circumstances, no one claimed responsibility, but the blame was laid squarely at the feet of the Syrian government and Russia. To complicate matters, Washington accused Moscow of interfering in the 2016 U.S. elections. As a consequence, prospects for an agreement between Moscow and Washington on a Syrian settlement came to an abrupt end.

Subsequent contact between Russia and the United States during the Trump administration did not bring about tangible progress, largely due to conflicting signals from the United States and apparent lack of urgency from Russia. By that stage it appeared Moscow’s strategy was to help Damascus regain the major cities and strategic highways, as well as establish Deescalation Zones to reduce the lines of confrontation between the Syrian government and the opposition, thereby allowing the government to gradually expand its control over Syria’s entire territory.

Regional Realignment

Another hopeful sign has surfaced lately: a regional realignment is taking place. It seems that the Gulf countries (with the exception of Qatar which is delaying the announcement of its policy shift until it coordinates with its ally, Ankara) have realized their past policies on both Syria and Iraq have allowed both Iran and Turkey to expand their influence in the region. In particular, these Gulf countries are reconsidering their policies vis-a-vis Syria and Iraq. Preliminary contact has been established between various Gulf capitals and Damascus and resuming diplomatic relations is being considered. There is also a heightened interest in returning Iraq to its natural place in the Arab fold. Economic relations are expanding between Baghdad and the Gulf countries and among Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt, in what is called the “New Sham” (New Levant), a new arrangement designed to enhance economic and political ties between the three countries. As part of this new orientation, Arab countries appear to be more open to mending their relations with both Tehran and Ankara.

A possible side effect of regional realignment may be the creation of a more realistic opposition that can act as a more effective interlocutor to the government in Damascus.

With the United States looking to reduce its military commitments in the region as exemplified by the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Gulf states must consider alternative arrangements to address the security concerns that Iran poses. They have the choice between confrontation or containment. Confrontation will result in uncontrolled escalation which the Gulf countries have no means to control, particularly with reduced American interest. Containment is the more plausible option. It includes cooperation on issues of mutual interest and confrontation when absolutely necessary. But more importantly, it requires taking Arab security cooperation to a different level, buttressed with support from the United States and the EU. It is not inconceivable that Russia, in one form or another, may participate in such a scheme. Moreover, better security cooperation between the Arab countries will help them articulate a common position that will enhance their negotiating power vis-a-vis Israel, Turkey, and Iran in the process of establishing a new security architecture in the Middle East.

Meanwhile, given the turmoil witnessed since the U.S. invasion, Iraqis seem to have realized that sectarian politics is detrimental to their long-term interests, as evidenced by the 2019 popular uprising. Furthermore, Arab nationalism appears to be making a comeback. Arab countries are also eagerly welcoming Iraq back in their midst.

Meanwhile, the Biden administration has taken a more pragmatic and realistic position regarding the region. It is trying to revive JCPOA in the hope of influencing Tehran’s future behavior. The administration is also trying to revive the prospects of the two-state solution and declared in a statement by Secretary of State Antony Blinken that Palestinians and Israelis “should enjoy equal measures of freedom, security, prosperity and democracy”. More recently, President Biden, in his address before the UN General Assembly on September 21, affirmed the U.S. commitment to a two-state solution. Furthermore, the administration is energetically pursuing a political settlement in Yemen, is more engaged in Libya, and appears open to serious discussions with Moscow on Syria.

While a U.S.-Russian understanding is a necessary condition, it is not sufficient. The Arab countries, particularly those who have a direct stake in the stability of Syria—Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan—need to move on two tracks. First, they must present an initiative for political settlement in Syria that would capture the attention of both Moscow and Washington, propelling the Syrian conflict to prominence among the many issues they are discussing. Second, they must ensure that Iranian and Turkish presence and influence in Syria and Iraq is addressed as part of the ongoing discussions to improve relations between the Arab countries and between Tehran and Ankara. Serious discussions between the Arab countries and Damascus linked to the issue of reconstruction are also necessary. A door may have opened with the recent deal providing Egyptian gas to Lebanon through Jordan, and more importantly Syria; this required the acquiescence of Washington. This development together with Washington’s acceptance of early recovery assistance for Syria incorporated in UNSC resolution 2585 may help reinforce the internal dynamic of reform and reconstruction.

Moving Forward

It is urgent to capitalize on these developments and move forward rapidly with the efforts to reach a political settlement in Syria. In addition to accelerating the work of the Syrian Constitutional Committee—a UN-facilitated mechanism created to aid Syrian constitutional reform—there is a need to move ahead in a creative manner with the full implementation of resolution 2254 as outlined above. In parallel it is necessary to address the matter of foreign military interventions in Syria, starting with the regional ones. This in turn will facilitate the process of establishing a regional security system in the Middle East.

Failure to do so would result in a failed state in Syria divided into zones of influence, with Idlib and parts of northern Syria under Turkish domination and the land east of the Euphrates controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) with U.S. support. However, the majority of the territory and population, which would include most of “useful Syria” from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates river will be governed by Damascus. Yet, no leader in Damascus can survive if he contents himself with such an arrangement. This is not a formula for long-term stability; it is a recipe for chaos in the region.

If Syria collapses, the entire region will be further destabilized. The nation-state system in the Levant may come to an end. There will be no prospect of stability in Lebanon. Centrifugal forces in Iraq will foreclose the possibility of a unified country. Fragile Jordan will come under increasing threat. With an unstable northern tier, it will only be a matter of time before Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Gulf is under strain. Non-contagious Egypt will also come under severe stress. Even Israel will not be spared. And the world will be sucked in, once again, to contain the ramifications of an even more unstable Middle East, thereby initiating a new, vicious circle of instability, foreign interventions, and dashed aspirations—and the people of the region will pay the highest price.

Ambassador Ramzy Ezzeldin Ramzy served as the United Nations Assistant Secretary General and Deputy Special Envoy for Syria ( 2014-2019). Before that he served as Senior Under Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Egypt, Ambassador to Germany, Austria and Brazil. He also served as Permanent Representative to the United Nations and other international organizations in Vienna.

Read More