The Case for Open Markets

Is the free trade party over? Competition certainly has its losers. But the widespread discontent with globalization misses a crucial point: only more trade, not less, will reverse the slowdown in world productivity.

A cargo ship passing by Hong Kong, South China Sea, Dec. 16, 2016. Christian Liechti/ Dronestagram

When Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson was challenged to name one proposition in economics that is both true and nontrivial, his answer was “comparative advantage.” Comparative advantage is the main force driving international trade: countries open to trade would export what they are comparatively “good” at producing, and import what they are comparatively “bad” at producing. “Good” and “bad” refer to production costs, which, in competitive markets, define prices to consumers.

Economists argue (and, in fact, have also empirically proved) that international trade makes countries, in the aggregate, better off; through imports, consumers living in countries open to trade have access to goods and services at lower prices than they would have in the absence of trade. The increase in the purchasing power of consumers—and thus their welfare—achieved through international trade is what economists refer to as gains from trade.

When digging into the distributional effects, we also know that while international trade makes some people better off, it also makes some others worse off. Thanks to trade, consumers will be able to enjoy lower prices due to increasing competition from abroad, but workers in those industries might lose their jobs. Yet, the phrase in the aggregate implies that the welfare improvement of consumers who benefit offsets the losses of workers who are hurt if their wages are reduced or they lose their jobs (even though workers are also consumers, and also benefit from the lower prices).

This tradeoff prompts a number of questions: How is welfare measured, and how is it aggregated? How can one possibly argue that allowing some people to save a few bucks when buying car parts offsets the fact that workers in local factories could lose their jobs? The difficulties in responding to such questions with simple answers—that is, without fancy mathematical models and highly complicated data analyses—is part of the reason that international trade is being questioned by large sectors of populations and exploited as a scapegoat for economic woes by populist politicians.

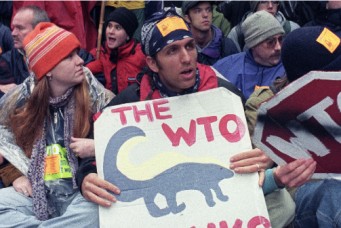

To be sure, some discontent with globalization is nothing new. But today we are seeing widespread dissatisfaction as reflected in such global events as the triumph of Brexit or Donald Trump’s election as U.S. president. Until now, international trade—and more broadly, globalization—was not such a controversial issue. On the contrary, the world as a whole embraced international trade, and most countries progressively eliminated trade barriers and created global institutions to further free trade. A large-scale multilateral effort to reduce trade barriers between countries resulted in the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, known as GATT, signed by twenty-three nations. The World Trade Organization (WTO), founded in 1995 as the successor to GATT, today has 164 member states. According to the WTO, more than four hundred regional trade agreements covering trade in goods or services have been created or reformed since the establishment of the WTO.

In 2017, it certainly feels like the free trade party is over. With the European Union about to formally lose its second-largest economy, and the Trump administration pushing (or at least saying it will) a protectionist agenda—withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), possibly imposing tariffs on China—international trade might slow down in the years to come.

Can protectionism revive the manufacturing jobs lost over the last decades in advanced economies such as the United States? Probably not.

To understand why, let’s look first at the rationale behind the claim that links trade to job losses. President Trump’s rhetoric suggests that American firms, by taking advantage of both wage differentials between the United States and countries like Mexico or China, have moved their factories abroad while serving U.S. consumers by exporting from those locations to the United States at no additional costs (as the result of low or no import tariffs due to trade agreements) beyond transportation.

Indeed, since NAFTA came into force in 1994, imports from Mexico to the United States have increased at a much faster pace than exports from the United States to Mexico. The U.S. trade deficit with Mexico has increased considerably, and stands today at about $60 billion. And since then, the United States has lost about five million jobs in the manufacturing sector. A similar case is made about China, with which the United States has its largest trade deficit, about $350 billion a year. The figures may seem to bolster President Trump’s argument, but the story is not so simple. Trump’s view of international trade is, to say the least, very unsophisticated. He is looking at the trade deficit to claim that the current trade deals are “unfair.” But there are a number of angles, and many more data points, that should be taken into account before making those claims and, more generally, before assessing the benefits from trade.

The Import-Export Conundrum

The notion that running a trade deficit is not a good thing is, at first sight, not outrageous. After all, in our day-to-day lives, we don’t want to spend more than what we earn.

Yet, is this the right logic? Not necessarily. Let’s look first at bilateral trade deficits. Often, the trade deficit with a particular set of countries is offset by a trade surplus with other countries. Overall, the United States has a trade deficit of about $450 billion a year. Bilateral trade surpluses with Hong Kong, Australia, Chile, and Brazil, for example, offset part of the deficit with countries such as China, Mexico, Germany, and Japan, among others. Thus, in this sense, the bilateral trade deficits are meaningless as they do not reflect the big picture.

President Trump’s obsession with the trade deficit might push his administration to take steps that might change bilateral deficits but won’t impact the overall deficit, which is the one that matters. For instance, imposing import tariffs on Chinese or Mexican goods will not really affect the overall trade deficit. Yes, goods and services from these two countries will be more expensive to the American consumer, and they might decide not to buy them. But will consumers find substitutes for those goods in America? Likely not. American producers rarely compete with Chinese and Mexican producers on the same goods or varieties of goods. Following the imposition of import tariffs, consumers will have to rely on countries other than China and Mexico that can competitively produce those goods and services. Even if imposing tariffs on China and Mexico could potentially reduce the U.S. trade deficit with them, it will most certainly increase it with other countries that are competitors of China and Mexico. The overall trade deficit will, at best, remain the same.

Now let’s turn to the aggregate trade deficit: is it bad for the United States to run a large trade deficit? It depends. America’s trade deficit accounts for about 2.5 percent of its gross domestic product. Not too high, but not too low either. Naturally, deficits create debt. But debt is not good only when either of two things occur: when it cannot be paid, or when others suspect it cannot be paid. That is not the case with the United States. In terms of public debt, judging by the markets, America is the safest country of all.

This takes us to the next, and perhaps more crucial, point—the overall trade balance won’t be affected by renegotiations, taxes, or tariffs. This is because the trade deficit reflects the existence of a more structural characteristic of the U.S. economy: the low levels of domestic savings. Basic macroeconomic accounting shows that the trade deficit equals the difference between domestic savings and total investment in the economy. The low level of savings is partly encouraged by the monetary policy put in place by the Federal Reserve following the Great Recession of 2008; low interest rates encourage consumption and discourage savings. Thus, monetary policy—which is not controlled by the executive—could play a role in reducing the trade deficit by encouraging Americans to save more. But this is particularly delicate in a still-recovering economy. Increasing the interest rate too much and too fast might roll back the post-recession progress that the economy has made.

All in all, the trade deficit is a reflection of the behavior driving consumption and saving decisions of the American people, and not of the “fairness” of trade deals. It’s as simple as that.

Productivity and Progress

Here’s a fact: all advanced economies lost jobs in their manufacturing sector, regardless of whether they were running a trade surplus or a deficit. The United States is not the exception, but the rule.

While the United States lost five million jobs in manufacturing since NAFTA was signed, it increased its manufacturing output by $800 billion. Thus, this additional data point that President Trump has ignored all along hints of a very, if not the most, important point: the vast majority of American jobs that vanished in manufacturing were lost to higher productivity. On average, American workers are able to produce 50 percent more today than they did in the early 1990s. Thus, most of these jobs weren’t lost to Mexico or China or any other country. They were lost to increases in productivity.

In fact, a few studies have tried to assess what portion of the job losses can be attributed to trade. The answer: not very many. The net job losses that can be attributed to trade with Mexico and China are estimated to be 100,000 and 300,000, respectively—a tiny share, less than 0.5 percent of the overall labor force.

These relative small numbers in net job losses reflect an important reality; while some jobs were being destroyed due to trade, many more jobs were being created thanks to trade. One way to look at this is by examining the nature of imports from Mexico to the United States. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, more than half of those imports are considered intermediate goods—capital goods, industrial supplies, and materials destined for production in the United States. On top of that, another close to 20 percent are intermediate goods for the U.S. automotive industry. The largest beneficiaries of Mexican goods are not consumers but rather firms. These firms have access to raw materials and intermediate goods that make them more competitive and able to sell their final goods not only within the United States but also to the rest of the world. It is likely that in the absence of free trade with Mexico, many American firms wouldn’t be able to compete in global markets.

By no means should we minimize the pain and suffering of those who lost their jobs. It is a fact that many workers became unemployed because the firms and industries for which they worked, sometimes for decades, were not competitive enough to survive the increasing competition from foreign imports. This is a very unfortunate outcome of international trade.

Yet, the damage can be contained without giving up on international trade. Given that trade results in welfare gains in the aggregate, redistribution can offset the suffering of those who lost their jobs or saw their (relative) wages decreasing over time. If the Trump administration truly wants to stand out from its predecessors, its response to the valid discontent among those adversely affected by international trade would be to provide safety nets for workers to transition to another career or, if necessary, to retirement. These safety nets are what has been missing from the equation. President Trump has the opportunity to become a champion of the middle class by putting away his anti-trade rhetoric and instead focusing on social programs that can offset the damage created by international trade among some communities.

Republicans and even some Democrats will oppose the safety net option. Why should the government be supporting workers who lost their jobs, many will ask. From the strict point of view of economics, they do have a point. Competition leads to job losses for some people. It is the nature of free markets, and therefore there is no justification for government intervention. But this time is arguably different: providing safety nets to workers who lost their jobs to international trade is the compromise that should emerge so that democracy and globalization can coexist together, and hopefully reduce the likelihood of future “shocks” to the system that can endanger both of them.

Harsh Reality

International trade is one of the catalysts in the process through which less productive firms die and other more productive firms are born. As part of these dynamics, workers and other resources flow from the least to the most productive companies or industries. The fast growth of South Korea and other Asian economies during the last half of the twentieth century is mostly the result of this process, as documented by many studies.

The world has been experiencing a productivity slowdown since the mid-2000s. While the fundamentals behind this slowdown remain unexplained, most economists agree that it represents the biggest challenge faced by the United States and other advanced economies. Nothing besides productivity growth can sustain long-run economic growth. It is more competition and more trade, not less, that is required to jumpstart productivity growth. Conversely, any policy aiming to reverse the advances the world has seen in free trade could have longstanding negative consequences to global economic growth. No worker, consumer, or politician will be immune to that reality.

Dany Bahar is a fellow in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution and an associate at Harvard University’s Center for International Development. On Twitter: @dany_bahar.