The Slow Violence of Climate Change

A warming planet places the heaviest burden on the countries and people least responsible for climate destruction. Survival necessitates justice, redress, and structural change.

An Egyptian farmer holds a handful of soil to show the dryness of the land due to drought in a farm formerly irrigated by the river Nile, in Al-Dakahlya, about 120 km (75 miles) from Cairo June 4, 2013. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

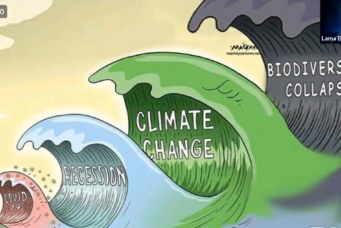

Over the next decade, the world is on track to break through the 1.5°C global warming threshold, which will mark the difference between survival and life-threatening conditions in many regions. In its Sixth Assessment Report, released this year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports that the world has already warmed 1.1°C from pre-industrial levels, signaling a “code red for humanity”.

For most parts of the Global North, the consequences of climate change are still in the early stages. In the Global South, on the other hand, climate change-linked environmental destruction has been impacting lives and livelihoods for decades. The irony of this, of course, is that the countries of the Global South have contributed the least to this crisis and the destruction of the planet.

The crises around the world are a result of relentless exploitation of natural resources by the Global North’s countries and multinational corporations over the past few centuries. As of 2015, the United States has been responsible for 40 percent of excess global CO2 emissions, followed by the European Union at 29 percent. Overall, the Global North has historically been responsible for 92 percent of the world’s excess CO2 emissions. Meanwhile, countries in the Global South, including those in the Middle East and North Africa, have been suffering for years from environmental degradation and will be hardest hit as climate change intensifies.

Already, countries in the MENA region are warming at double the global rate, and breaking historical records. In 2021, countries such as Kuwait, Oman, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, and Iran reached temperatures above 50°C (122°F). Children growing up in the Middle East today are exposed to more heatwaves, droughts, and crop failures than anywhere else in the world. Youth born in the region in 2020 are over seven times more likely to be exposed to extreme heatwaves over their lifespan, compared to adults born in the 1960s. Continued warming beyond 1.5°C will have life-threatening consequences.

Meeting these challenges and preventing the worst requires systemic changes in the world, from making deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions and addressing historical global injustices, to preparing communities for severe climate, socioeconomic, and health impacts.

Warming and Conflict

While climate change may not directly cause conflict, it can exacerbate existing divisions and grievances in societies where historical animosities exist, where socioeconomic inequality is prevalent, where people’s livelihoods are negatively affected by environmental degradation, and where institutions are weak. In these settings, climate change shocks will be extreme risk and threat multipliers, intensifying competition over scarce resources, and exacerbating existing societal fractures.

Climate change-linked natural disasters are expected to amplify and worsen inequality and poverty in fragile societies. This is likely to stoke divisions and lead to confrontations among vulnerable and desperate communities. The result of this in many fragile settings, according to the research by Halvard Buhaug and Nina von Uexkull, will be a “vicious circle, locking affected societies in a trap of violence, vulnerability, and climate change impacts”.

In Syria, for instance, unprecedented drought and agricultural failures between 2006 and 2009, which scientists have attributed to climate change, resulted in loss of income, impoverishment of rural areas, mass migration to urban centers, and intergroup disputes. The consequences of this drought are seen as some of the main factors that led to the 2011 uprising against the government of Bashar Al-Assad, which resulted in a brutal and protracted war.

In an address to the UN Security Council’s session on climate and security risks in April 2020, International Crisis Group President and CEO Robert Malley highlighted that around the world, “climate change is already shaping and will continue to shape the future of conflict”. This extends beyond state borders, with tensions already rising between governments, as in the case of Egypt and Ethiopia over the River Nile waters. Countries in the MENA region are the most water-stressed in the world and share many of their sources including aquifers, rivers, lakes, and seas. At the same time, the region’s institutions often lack the capacity to manage these resources sustainably, and this is exacerbating the risk of dispute.

Climate change is already aggravating water shortages and land degradation in the region, negatively impacting agriculture, livestock farming, and people’s livelihoods. In North Africa, protests over access and quality of water, linked to climate change, urbanization, population growth, increased demand, and limited supplies, have been taking place for years. In Syria and Iraq, more than 12 million people have lost or are in the process of losing access to water and are considered water insecure—a remnant of failing governments and years of conflict. On top of the historical trauma, water insecurity is a chronic psychological stressor that results in serious psychological consequences, such as depression, a sense of hopelessness, and even suicide.

In some cases, access to basic necessities such as water is used as a tool of suppression. The Occupied Palestinian Territories, for example, have for years faced a water crisis owing to Israel’s repression of the Palestinian people. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in the West Bank have limited access to clean drinking water, while only 10 percent of the population in Gaza can access it at all. In Gaza, 12 percent of childhood deaths are linked to intestinal infections that are related to clean water shortages.

As problems like these intensify, people will increasingly be forced to leave their homes, leading to another major outcome of climate change in the region.

Forced Displacement

Forced displacement due to climate change will be one of the biggest humanitarian challenges facing the world in the twenty-first century. Intensification of environmental degradation and natural disasters in the years to come will displace millions of people around the world. Some will be displaced in their countries, while others will be forced to become environmental migrants or refugees. Climate change-related displacement will negatively impact the Global South the most, including the MENA region, as most countries are not ready to deal with internal displacement or the inward movement of people from other countries.

Available data shows that displacement due to climate change is already on the rise globally. In 2020, there were over 7 million displaced people in more than 100 countries due to disasters that took place in 2018 and 2019. Since 2020, disasters such as floods, storms, droughts, wildfires, and other hazards have disrupted the lives of over 130 million people, forcing more than 30 million people to flee their homes and communities.

The World Bank estimates that by 2050 climate change will displace more than 216 million people around the globe, including 19 million people in North Africa. This will lead to enormous human suffering and, unless managed effectively, cause new disputes and possibly even armed conflict between the displaced and hosts. This displacement will also lead to trauma and mental health challenges of enormous proportions.

Mental Health Impacts

Climate change and environmental degradation that are intertwined with conflict, political violence, and oppression can in some cases unravel quickly and devastate societies, as in the case of Syria. The mental health impacts of the Syrian war and ongoing human rights abuses have been profound.

In other instances, the “slow violence”—a combination of gradually unfolding environmental catastrophes and related vulnerabilities and stresses—negatively impacts societies and communities over the years and decades. Slow violence evades boundaries and stretches across time, insidiously subjecting people to daily struggles and added traumas.

Over a lifespan, people living in conflict-affected areas can be exposed to multiple psychological adversities that are either directly experienced, witnessed, or anticipated as the climate crisis deepens. Around one in five people in conflict zones struggle with mental health challenges, such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress. Children living in conflict areas in the Middle East are particularly vulnerable, reporting significantly higher levels of traumatic stress. As climate change progresses, it is likely that those living in the MENA region will be exposed to even greater hardships.

A combination of environmental degradation, violence, physical destruction, displacement, and mental health challenges and traumas in conflict zones and other fragile settings will reduce the ability of many people and communities to adapt to climate change, cope, and survive. Expanding access to mental health care services is essential. It is important to remember, however, that global climate injustices are psychologically, socially, and politically harmful, and these unjust social arrangements require practicable socioeconomic and political solutions.

Communities, countries, regions and the world as a whole must act urgently. Any meaningful solutions must include structural and systemic changes if they are to have an impact for the vulnerable people and communities in the MENA region and elsewhere in the Global South.

A Call for Systemic and Structural Change

There is considerable agency in fragile and conflict-affected areas where communities resist ongoing violence and seek to sustain and restore a sense of self and cultural identity. Yet, as forms of structural violence, global climate injustices continue to undermine the future of much of the world.

Systemic and structural changes that are needed on the global level are not only about the way forward regarding renewables, cutting down emissions, and slowing down global warming. Changes are also needed when it comes to capitalist exploitation and extractivism, geopolitical machinations by powerful countries, and climate justice and reparations. This will require the dismantling of coloniality and Euro-American global hegemony, and genuine socioeconomic, political, and epistemic decolonization around the world.

Climate change scholar Farhana Sultana highlights that “climate justice is about systems change and addressing structural inequities and power systems that uphold those inequities”. Anything less will maintain the unjust and destructive status quo.

The geopolitical and economic interests of powerful countries are likely to continue to shape and impact life and politics in the MENA region and elsewhere in the Global South. Ideological and geopolitical interests and pressures will complicate the already complex political and security relations in the region and the ability of countries to prioritize and manage climate change risks.

Western interests, extractivism, and neocolonial hegemony are interlinked with the Euro-American hegemony in knowledge production and education, often complementing each other. Research byCarbon Brief shows that climate science continues to be overwhelmingly dominated by scientists from the Global North. This is creating significant “blind spots around the needs of some of the most vulnerable people to climate change, particularly women and communities in the Global South”.

We should be wary of the solutions designed and proposed by the scientific elites from the Global North, based on Euro-American dominant discourses, interests, and provincial worldviews. Communities and scientists on the frontlines of the climate crisis in the Global South must shape solutions for their own societies and regions. Solutions and actions must be based on the lived experiences, needs, and interests of those affected, with meaningful considerations placed on socio-historical factors.

Conflict-affected and war-torn countries are the most vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters, as instability undermines their capacity to respond. This is why conflict management, peace-building, and post-conflict reconstruction are key, not only for ending violence and rebuilding societies, but also for creating capacity and institutions to address and manage climate change.

As time passes, the prevention and mitigation of new conflicts will be as important as the responses to climate change itself. Governments, leaders and conflict management experts will have to work with communities to mediate and resolve disputes and find ways to collaborate in order to come up with solutions for the challenges and realities brought forward by climate change.

At the United Nations Security Council, the engagements and negotiations on a climate security resolution are ongoing. A formal resolution would be the first of its kind, recognizing climate-linked instability, conflict, and security risks and providing a platform for regular engagement and recommendations on how to tackle and minimize them.

Dealing with climate change must become a priority for leaders in the MENA region and beyond. This will require changes in the way oil-rich MENA countries deal with extractivism driven by the Global North. The rich Gulf countries will also need to decide whether they want to work in collaboration with other countries in the region to mitigate and adapt to climate change, or whether they will act in self-interest only, developing local solutions and building walls to prevent climate and conflict refugees from coming in, as the Global North is already doing.

While global climate financing for the transition to renewables is slowly trickling in, there is a lack of meaningful investment that takes into account the historical injustices that make the Global South vulnerable today. Climate reparations present an option to ensure that those who have benefited from colonial and neocolonial exploitation and who continue to contribute to the climate crisis are held responsible for their actions.

Climate reparations may include negotiated settlements between governments of the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, who have benefited the most from fossil fuels and are overwhelmingly responsible for the global climate crisis, and countries that have been disproportionately affected by extractivism and climate breakdown. Financial reparations can be used to build capacity, infrastructure, and health and social programs needed to adapt to the shocks of climate change. Climate reparations can also include litigation for the losses and damages, including psychological trauma, that have resulted from the harm done by Western governments and multinational corporations.

Climate reparations are part of climate justice. But the issue of reparations is easier said than done. The list for Global North reparations is long, including slavery, colonial oppression, and looting, and this is not going anywhere. Thus, climate reparations may never happen, and the countries in the Global South may need to consider alternatives.

Easy or straightforward solutions to get us out of the upcoming crises do not exist. While we will not be able to prevent climate breakdown, countries and communities around the world—and particularly the vulnerable and fragile countries in the Global South—will have to continue with engagements, preparations, and adaptation.

The 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26), a follow-up to the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference, was seen as a make or break event where systemic and structural changes needed to be made. However, due to the lack of political will to make fundamental changes, the negotiations in Glasgow did not lead to the agreements necessary to bring greenhouse gas emissions under control. According to the Climate Action Tracker, the world is still heading for catastrophic warming of 2.4°C this century.

Extractive industries and multinationals had an overwhelming presence at COP26, protecting their own interests and influencing the outcomes of the negotiations. The United States and the European Union, most responsible for global climate destruction historically, have undermined the creation of a funding mechanism for rich countries that have benefited from the exploitation of the Global South to pay for climate damages they have caused.

Critical engagement on the Global North’s historical and current role in pillaging the Global South, and whether the needed changes can come under capitalism, was wholly absent. The world’s militaries, which are some of the largest emitters, continue to be exempted from the negotiations about the planet’s future.

Climate security and the links between climate change, instability, and conflict were not on the COP26 agenda. Nor were human rights and reparations. All this, and much more, will have to be on the agenda of COP27—which will take place in Egypt in November 2022—if we are to survive in this century.

Garret Barnwell is a clinical psychologist and community psychology practitioner. He is also a University Research Committee Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Johannesburg. He has over ten years of community psychology experience, including in the humanitarian sector, and has worked in South Africa, Somaliland, as well as Lebanon and Turkey on the Syria war, among other countries. He is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. On Twitter: @BarnwellGarret.

Read MoreSavo Heleta is a researcher and educator with more than ten years of experience in South African higher education, currently working as an internationalization specialist at Durban University of Technology in South Africa. He is a survivor of the Bosnian war and is the author of Not My Turn to Die: Memoirs of a Broken Childhood in Bosnia. He is based in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. On Twitter: @Savo_Heleta.

Read More