The U.N. Climate Summit and Its Aftermath

Developing countries see the call for equal actions with their richer counterparts as serving the interests of the latter.

A delegate walks at the venue of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland, Britain, November 9, 2021. Yves Herman/ Reuters.

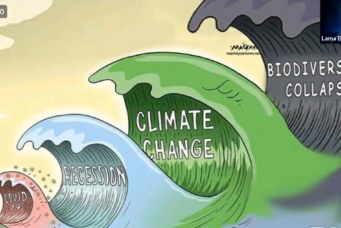

The last few months have put a spotlight on the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly referred to as COP26 summit or the ‘Conference of the Parties.’ Anticipating the meeting in Glasgow, Scotland, many described the summit as a turning point for the international community, in which it must choose between an earnest commitment to end practices which harm the environment and aggravate climate change, and between the continuation of excessive consumption patterns and the production of noxious emissions which both destroy our shared wealth, create a hostile climate, and may inevitably lead to our own extinction. This effort was led by U.N. Secretary General António Guterres, who warned that the world is on a path to self-destruction through its greed and disregard.

After the United States returned to the Paris Agreement once U.S. President Joe Biden assumed office, many observers were optimistic about renewed efforts to combat climate change, and voices proliferated calling for strong, collective action to resolve the clear contradiction between a status quo characterized by energy production from traditional sources such as oil, natural gas, and coal as well as the eradication of forests for the sake of urban expansion and development, and between the pursuit of a safe and healthy future for posterity. These calls have acquired new urgency given clear climatic consequences observed in recent times, including the rising degrees of heat each year and the deleterious impact of climate change on food security, water sources, and sea levels.

In my opinion, the Glasgow summit succeeded in accentuating the dangers of climate change and helped establish the objective, scientific view that our excessive consumption patterns are destructive to the planet and increase risks in the long term. The political momentum behind COP26 has also muted the voices of climate skeptics, at least in the short term.

Another positive aspect of the summit was its affirmation that addressing this existential challenge to the Earth requires collective and comprehensive action, since climate and environmental changes transcend international borders and state sovereignty. Furthermore, it is impossible to achieve the desired results without a comprehensive plan to adjust overconsumption, whether in the energy sector or in the extraction and use of other natural resources which have an adverse impact on bio-diversity and vital bio-physical systems necessary for our survival. A comprehensive plan of action is also needed to counter the consequences of decades-long, harmful environmental policies, to create emissions offsets globally, and to ensure a less harmful production and development path for all reaches of the world.

The summit accompanied a number of agreements to stop the destruction of forests, lower methane gas emissions, limit future warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, and reduce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions.

However the summit also brought to the fore clear tensions in the international community, such as commitments about the specific time frame to reach net-zero emissions, identified by years 2030, 2050, and 2070. The international community also failed to meet its commitments to equip a large monetary fund that will assist developing countries transition from the use of traditional energy resources and old, polluting consumption technologies to more modern ones. Such a fund would facilitate that transition by assisting the structural development of a green economy, the preservation of the environment, and measures to counter or ameliorate the effects of climate change. It is no secret that diverging positions on these matters are generally connected at the core with state interests in achieving impressive rates of growth, which for many countries entails cheap, traditional sources of energy deleterious to the environment and the climate. A second distributional disagreement concerns who bears the cost of transition from one technology to another. Many developing, or less-wealthy countries perceive that “the call for equal contributions between countries with diverging degrees of growth serves the interests of more wealthy countries. They exploit efforts to protect the environment so as to create unequitable and unjust conditions. This fact is especially egregious given that the largest contributions to climate change have been the ill-advised and exploitative policies of large, rich, and industrialize countries.”

I very much agree with this statement and its connecting arguments, for the consequences of climate change are not new, as they reflect accumulations over the past hundred years. I also believe that developing countries have an inalienable right to development at the lowest possible cost. This is the same principle that their independent, industrialized counterparts in the Global North embraced in the past. And yet, I do not see a benefit of wasting time with a superfluous debate over the established facts, whether denied by industrialized countries or censured by their developing counterparts, because all of us will pay a heavy price for not quickly confronting climate change and the misuse of our environment.

Rather, I prefer that we maintain that the Global North fulfills its commitments to enable developing countries to transition from energy sources that do not harm the environment, such as renewable energy, whose prices at the moment remain high compared to oil, gas, and coal. Support must also be directed to moving the developing world’s productive industries toward more modern and less environmentally destructive technologies. Such support should exceed the mere provision of depletable resources; it must help implant clean technologies in developing countries with moderate costs so that the issue of the environment does not become another one-way, commercial transaction between rich manufacturer and less-developed consumer, as opposed to a healthy and all-inclusive relationship.

I also advise European countries to include in the framework of the Union for the Mediterranean and its seat in Barcelona a special fund to support developing countries around the Mediterranean as they adapt to climate change in the region, which has endured rates of warming exceed 20 percent of the global average. I see the necessity of establishing another special fund internationally to help African countries adopt modern, clean technologies in the continent’s persistent quest to join the development train, especially with its rising rates of growth after suffering many decades from the adversities of colonialism. And I suggest the United Nations and its institutions concerned with climate change to quickly evaluate the new commitments, the extent of their implementation, and the areas where rapid action is required. These are initial and incomplete suggestions; however it is appropriate to take them seriously, especially as Egypt has offered to host the next summit, COP27, and has announced that it will expedite its transition to alternative energy which will form 46 percent of its consumption over the next decade.

Nabil Fahmy is a former foreign minister of Egypt. He is also Dean Emeritus and Founding Dean of the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the American University in Cairo. He served as Egypt’s ambassador to the United States from 1999 to 2008, and as envoy to Japan between 1997 and 1999. On Twitter: @DeanNabilFahmy.

Read More