Thinking Arab Futures

Drivers, scenarios, and strategic choices for an improved Arab World

In fundamental ways, the future is the only thing that really matters; how a society will fare in the years ahead is, and should be, the central concern of policymakers. A focus on the future necessarily has three elements: an examination of what the key drivers, scenarios, risks, and opportunities in the future will be; a vision of what kind of future one wants for one’s society; and a plan for how to get there.

The field of “future studies” is not about the impossible task of predicting the future, but rather about examining key drivers and dynamics that will likely be at play, thinking creatively and rigorously about what various scenarios and outcomes might look like, and helping decision-makers chart a course within imagined possibilities. Future studies is an activity that organizations, corporations, and states are increasingly engaged in, and ignore at their peril. A limited amount of work has been done to explore the various drivers, dynamics, and scenarios that might impact the Arab World and the Middle East, but such an endeavor is fundamental for scholars and pundits alike.

With regard to having a vision of the future, the Arab World is at a moment of particular passivity: I would say that in the past, we used to have a future. Past generations had vivid ideas about what a better future would look like, and focused their efforts to bring that about. When the American University in Cairo was established a century ago, a host of intellectuals throughout the Arab World promoted the vision of a liberal future based on humanism, pluralism, secular nationalism, and democratic government. After World War II and the establishment of Israel, Arab nationalists promoted a statist vision of the future, in which strong states would provide economic progress and social justice at home and victory abroad. Arab leftists promoted a socialist view of the future in which progress would be achieved through restructuring international and domestic economic relations. Islamists have argued that securing a strong future consists of reviving a golden Islamic past. Some of these visions of the future clashed in the events of 2011 and their aftermath; liberals and Islamists promoted competing visions of the future, while statists generally won out in the end.

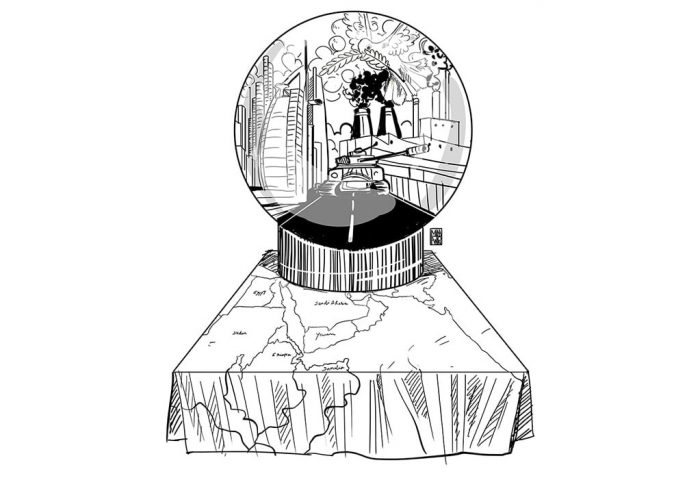

Our current Arab World is suffering from a “future deficit,” in that ambitious dreams for an alternative and profoundly better future have been shoved aside in favor of the short-term goals of maintaining stability and security, and avoiding civil war or state collapse—all worthy, but not transformative long-term objectives in themselves. A society needs a strong vision of its future in order to marshal national resources and policies in a proactive and transformative manner. As a wit once said, “If you don’t have a sense of where you want to go, you are likely to end up somewhere else.”

Gray Rhinos, Gray Swans, and Black Swans

Most readers will be familiar with the term Black Swan, used to denote a highly improbable and unpredictable event that has sharp and wide-ranging consequences. The events of September 11, 2001, or the immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi in December 2010 could be described as such events.

A Gray Rhino, meanwhile, is almost the opposite: a highly probable, highly visible, highly impactful yet neglected threat. The Gray Rhino is akin to the “elephant in the room” that everyone is aware of but does not want to acknowledge or deal with. In the Middle East, certain trends like elevated demographic growth, persistent unemployment, or the future effects of climate change are such Gray Rhinos.

Gray Swans are events that can be anticipated to some degree, whose likelihood is difficult to determine, but whose effects would be very significant. They lie somewhere between the obvious Gray Rhinos and the invisible or unpredictable Black Swans. In this essay, I connect a number of Gray Swans to a “future horizon” in order to explore how they would affect the future of the Middle East. This future horizon I have in mind is not a fixed point in time, as the realm of future reflection is always imprecise and hard to delimit with much accuracy; but I am thinking within the horizons of roughly 2025–35—that is, not the immediate short-term future, nor the longer horizons of 2050 and 2060—but far enough away that broad drivers and scenarios can have a significant impact, but still close enough to be able to see many of the elements that will likely be in play.

In the paragraphs below, I will examine a number of Gray Rhinos as well as Gray Swans. I will leave Black Swans out of my sketch, as they are almost by definition impossible to spot beforehand with any great usefulness.

Gray Rhinos: Long Term and Underlying Drivers

The Arab Middle East will remain a region of high stress for the foreseeable future. And this is due to a number of underlying demographic, economic, technological, and environmental drivers. The underlying drivers are set to have long-term impacts in the Arab region’s future, and are likely to be the cause for high levels of socioeconomic and political stress. Yet, how these forces will interact with political institutions, regional dynamics, and unforeseen Gray Swan or Black Swan events, is much harder to foresee.

Demography

As Barry Mirkin explains in his 2010 report “Population Levels, Trends and Policies in the Arab Region: Challenges and Opportunities,” the population of the Arab World has increased by about three times since 1970, rising from 128 million to 359 million. In total, Arab nations are expected to have 598 million people by 2050—some 239 million more than in 2010. While this could be a boon if economies were healthy and labor was scarce (as in some of the developed countries), in the Middle East unemployment is high and economies have been slow to produce jobs. Consequently, this high demographic growth will further swell the ranks of the unemployed and put additional pressure on economic, social, and political institutions.

Economics

None of the large-population economies of the Arab World has managed yet to move on from the rentier and semi-protected models of economic management to the high-growth, high-employment export-led models that bore fruit in East Asia, China, and—closer to home—Turkey. Some of the smaller Gulf states, like the United Arab Emirates, have leveraged oil rents to create a vibrant and diversified economy, and Saudi Arabia is trying to do the same in its Vision 2030. However, whether or not the Saudi attempt will succeed, it seems unlikely that large-population Arab countries like Egypt and Morocco will be able— without oil leverage—to achieve the high levels of growth and low levels of unemployment that they so desperately need. Arab youth unemployment is already the highest in the world, at 25 percent, and it is likely to remain high in the foreseeable future as millions more young people stream into strained job markets across the Arab region.

Land, Water and Climate

In a 2002 article by Farzaneh Roudi-Fahimi et al. titled “Finding the Balance: Population and Water Scarcity in the Middle East and North Africa,” we find that the Arab World is already the most land stressed of any region on the planet, with only 5.6 percent of land available for agriculture. It is also the most arid and water stressed of any area in the world, with 6 percent of the world’s population but only 1 percent of its water resources. The region’s main rivers all originate from outside the Arab World and the region’s underground aquifers are being depleted at an alarming rate. Sanaa is the first world capital that is scheduled to run completely out of potable water. Affluent societies are able to afford desalination plants, but this is not an option for the vast majority of the region’s populations.

Climate change has already brought about precarious rain patterns and rising temperatures. The 2008 United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that the Middle East and North Africa region will see declining rainfall of 10 to 25 percent, declining soil moisture of 5 to 10 percent, declining water runoff of 10 to 40 percent, and increasing evaporation of 5 to 20 percent.

The threat to food security is large and direct. Part of the Syrian uprising was the result of historic droughts in the country’s agricultural north, and summer temperatures in Baghdad and Kuwait have broken all records. Climate forecasts warn of unlivable temperatures in parts of the Persian Gulf and North Africa, drastic changes to rain and drought patterns, and rising sea levels that could impact millions of people in the Egyptian Delta and elsewhere.

Energy

The region’s main economic resource remains its hydrocarbons. And indeed we are still living in the global age of oil, but we are on the tail end of it. Oil prices have already seen dramatic fluctuations. Most forecasts generally predict the continuing relevance of hydrocarbons in the global energy mix through at least 2040. However, shale oil in non-Middle Eastern economies has already changed the energy markets, and any major technological breakthroughs relating to alternative energy production (solar, wind, thermal, or even nuclear) or relating to energy consumption (example: electrification of transportation) could greatly impact hydrocarbon prices. A sustained collapse of oil and gas prices would decimate the economies of the Persian Gulf and Iraq as well as Algeria, and have dramatic ripple effects throughout the region.

Urbanization

The majority of Arab citizens already live in cities; this trend is projected to grow to 60 percent and beyond in coming decades. Increasing urbanization will strain already stretched infrastructure in housing, electricity, water, and job creation and will create challenges for governments struggling to maintain control over increasingly mobile, demanding, and volatile populations.

Technology

We are living through an age of technological revolution. Changes in communication technology in the past two decades ended Arab states’ monopoly on information, created webs of informed and mobilized citizen groups, and greatly contributed to the upheavals of 2011 and beyond. Arab governments are trying to learn—from the Chinese and others—how to control this new information dragon and regain their dominance, but the top-down monopoly has already been broken.

Significantly, there are other technological developments on the horizon, like further breakthroughs in artificial intelligence and robotics, which could have incalculable impacts in the Arab World. On the economic side, such breakthroughs could render work even harder to provide or find, and raise unemployment rates even further. Alternatively, or concomitantly, they could bring down the costs of production and create more value in the economy without the traditional mechanism of employment to share the wealth. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence could strengthen the surveillance and control capacities of governments; they might also be used by terrorist groups, as a form of cyber weapon, in a completely different direction. Technology will be one of the key wildcards in the near future.

Gray Swans: Pivot Points toward Alternative Scenarios

Although we can develop a sense of the main drivers in the future, it is never clear in what exact direction these Gray Rhinos will roam. Yet, Gray Swan scenarios tied together with Gray Rhino drivers begin to give us clearer pictures of how possible Middle East futures may play out.

Gray Swans share with Black Swans a high level of strategic impact, but Gray Swans are events that are easier to spot and analyze. They can be found by “scanning the horizon” of our current conditions. I will consider Gray-Swan events as they relate to three key players in the Middle East: Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt.

Iranian Swan

Any significant change in Iran will have a dramatic impact on the Arab World. The main Gray Swan event there is likely to relate to the death of the current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. That moment of succession will bring out a number of internal tensions and contradictions within the Iranian regime itself, but also between the regime and a disgruntled public. Iran could move in any one of several directions: (a) the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) could consolidate their hold on the state and move the country more firmly toward what would effectively be military rule; (b) the current system could be preserved, with a new supreme leader continuing Khamenei’s role of power balancing between the IRGC and more moderate elements of the regime; alternatively (c), the death of Khamenei could spark a series of events, including mass public protests, that could push for movement away from both theocracy and hardline IRGC policies toward a more fundamental change of the Islamic regime.

While it is impossible to predict which way that swan will fly, it is important to look toward that pivotal moment and consider the possibilities. It might also behoove Arab leaders and opinion makers to consider what they could do to make a more favorable turning in Iran’s post-Khamenei foreign policy toward the Arab region more likely.

Saudi Swan

Saudi Arabia is in the process of a major transformation. Its previous trajectories of state-led welfare rentierism and socio-cultural alliance with hardline religious elements were unsustainable. Success and development in the kingdom rests on the new economic and socio-cultural transformations that have been enacted by Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman and his cohort of young leaders.

Bin Salman has transformed the management approach within the royal family from one of power sharing to one of centralizing almost absolute power; he changed the relationship with the business class from one of laissez faire to a much more aggressive approach; he has ended decades of state accommodation for religious radicals and is leading a dramatic cultural opening of Saudi culture and society. But at the same time, he has greatly increased the levels of repression against critics and rivals, in ways that have raised serious concerns, particularly in the West.

Any of the economic, political, and socio-cultural changes would be challenging on their own, let alone trying them all at once. Suffice it to say, the crown prince himself is a Gray Swan: he could succeed spectacularly and bring about a Saudi Arabia transformed almost beyond recognition, or his efforts may crash and burn either through his own mismanagement or through conditions beyond his control. In this negative scenario, Saudi Arabia could find itself facing a new set of challenges both in terms of ruling family cohesion and ability to govern and rising discontent in the eastern part of the country, or serious foreign policy challenges abroad.

Swans upon the Nile

It is no secret that Egypt faces a staggering array of demographic, economic, political, environmental, and security challenges. In a sense, one can say that in Egypt several Gray Rhinos roam. And whither goeth Egypt, a great impact will be felt not only in the rest of the Arab World and the Middle East, but also in Europe, Africa, and the world at large. Some may posit that Egypt is too big to fail; yet if the country fails, the shock waves will be enormous. The current administration in Egypt is banking largely on a Chinese model of development,

in which the government maintains and increases centralized control, while leading ambitious economic reform and development programs. China rode this model to double-digit growth and an economy that now rivals that of the United States.

Indeed, the administration of President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi has taken a number of important steps to grapple with a number of the Gray Rhinos that roam the land, such as economic growth, job creation, energy needs, water security and the like. And while it is a long shot to expect that the Egyptian government, with its current set of institutions and resources, could recreate anything like the Chinese miracle, it is within the realm of possibility that the current trajectory could produce enough economic development and job growth to keep the country relatively stable.

The Gray Swan gamble is what happens if this attempt fails, or at least fails to keep up with the galloping demographic, economic, and environmental pressures in the country. What would the signposts of failure look like? Might failure in Egypt be an unravelling around the edges such as we’ve seen for years in Pakistan, and that we already see to some degree in northern Sinai? Or, would it unravel into a form of internal civil war or proxy struggle that we’ve seen in several Arab countries? Or might it manifest just as a slow but massive stream of millions of economic and environmental migrants heading north?

Perhaps an Egyptian failure is too big to contemplate and just impels us to focus on avoiding it. Yet, it remains the biggest swan in the region—and one that we ignore at our peril.

Geopolitical Context

When exploring these various rhinos and swans, it is also important to be aware of the political and geopolitical contexts in which these forces will be interacting. These include conditions of fragile states, a broken regional order, and a changing set of global dynamics impacting the region.

Fragile States

The Arab Middle East is, and is likely to remain, a region of fragile states for the foreseeable future; four key states fully or partially collapsed in the past decade alone—Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Iraq (and Sudan split in two)—and a few others (Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Bahrain) came close to catastrophe. Today, Algeria and Sudan are on the brink. The causes of this fragility are unlikely to be resolved soon, and the Middle East will continue to grapple with the challenges generated by failed states, the challenges of rebuilding them, and the challenges of shoring up fragile states. The corollary of weak and broken states is the rise of armed non-state-actors and terrorist groups.

While there have been gains against some of these main groups, like ISIS, after much concerted international effort, the challenge of these groups is likely to bedevil the region for many years to come.

Fractured Region

The Middle East is the most disordered region in the world. It is home to a high number of conflicts (Iran vs. United States; Iran vs. Israel; Iran vs. GCC; intra GCC; Shia vs. Sunni; Israel vs. Arab; Turkish vs. Kurdish; states vs. non-state¬actors) and is a region without an inclusive security or political architecture. The Arab League itself is divided and all but defunct, and there is no framework that integrates or seeks to reduce conflict and increase cooperation between the Arab states and the three powerful non-Arab states of the region: Turkey, Iran, and Israel. The absence of any secure, stable, and minimally cooperative regional order has been a main driver of low economic development, high spending on defense, costly civil wars, and state collapse. Also, this lack of regional order has led to the rise of sectarian and ethnic armed non-state actors, in many cases supported or enabled by regional proxies. Most signs indicate that this regional disorder is likely to endure into the foreseeable future.

Global Contestation

The Middle East has long been a region of global contestation. For much of the second half of the twentieth century, its geopolitics was largely determined by the bipolar dynamics of the U.S.–Soviet Union Cold War. The period of

U.S. hegemony after the collapse of the USSR brought a decade of relative stability in the 1990s but then led to a destabilizing decade of U.S. intervention after September 2001, mainly in Afghanistan and Iraq, but also through War on Terror operations in other countries of the region. The U.S. actions which were intended to weaken Iran, strengthened it; intended to consolidate Russia’s exclusion from the Middle East, enabled its return through Syria; intended to defeat terrorism, witnessed its spread.

The new U.S. National Security Strategy, unveiled under the Trump administration, recognizes that great power competition—particularly with Russia and China—has returned as the main driver of security and foreign policy concerns. There are obvious arenas of such competition in Eastern Europe and East Asia, but the Middle East also will be an arena of great power competition in the years ahead. Whether this will exacerbate proxy and regional wars, or alternatively be used as a means to leverage international cooperation in order to de-escalate regional and proxy conflict in the Middle East is yet to be seen.

General Scenarios

While Gray Rhinos, Gray Swans, and geopolitical contexts (to say nothing of the unforeseen Black Swans) can generate an incalculable number of outcomes, it is helpful to sketch out three general scenarios that try to bundle myriad outcomes into broad future pathways. These three scenario bundles are the following:

(a) a “muddling through” scenario, without much dramatic improvement or collapse; (b) a pessimistic worst-case scenario; and (c) an optimistic scenario. In a study called “Arab Futures: Three Scenarios for 2025” led by Florence Gaub, her team labeled these three scenarios the Arab Simmer, the Arab Implosion, and the Arab Leap. While these futures are not predictive in any way, the categorization of possible futures is a useful step in beginning to organize one’s assessment of the future, and begin to grapple with how one can make the worst cases less likely, and the optimistic scenario more likely. It is also important to note that these pathways should not be thought of as three discrete and separate possibilities, but rather as bundles of dynamics and developments that have been grouped together for purposes of examination and reflection. They should be considered side-by-side, as any realistic unfolding of the future will probably have elements of all three.

Muddling Through

In a way, this is the most natural view of the future, as most people generally expect what will come to resemble some form of extension or elaboration of the present. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. And indeed, there are many solid arguments for this form of continuity. Dramatic change is not always the rule in history. And in the Arab World, one can make the argument that many Arab states, societies, and economies have faced a large number of the challenges that we have outlined above and still managed to survive in recognizable form. In any case, this muddling through scenario would posit that the Arab region will continue to be challenged by a large number of the drivers and uncertainties outlined above, and that it will remain a region of strained economies, high youth discontent, and fragile states. On the other hand, this scenario would also posit that some of the civil wars will wind down and reconstruction will commence; that governments will provide at least a modest level of economic growth and job creation; and that socioeconomic and political pressures will remain more or less contained without a major explosion or implosion. This muddling-through future could prevail at the region-wide level, even if a few countries in the region, like Syria, fail to recover from civil war, or if others, like Lebanon or Bahrain, stumble. This pathway is generally what policymakers, both in the region and internationally, and in public and private sectors, might normally expect and prepare for, even if only out of lack of imagination.

Things Fall (further) Apart

The modestly comforting presumption that things tomorrow, next year, next decade, will be more or less similar to things today, might be a natural psychological trope, and might even be buttressed by a number of sound arguments, but dramatic downward spirals are also a common occurrence in history. Few in Europe in 1910 imagined that the continent would enter another Thirty Years’ War that would leave tens of millions dead and the continent devastated and transformed beyond recognition. Few in the Middle East in December 2010 saw the series of history-bending events that would unfold in the months and years ahead.

If we look at the underlying drivers, or Gray Rhinos, that we outlined at the outset of this essay, we can see that the drivers are going from bad to worse and may result in any number of events. And if we look at the developments of the past decade in the Arab World, there too we can see that the situation has gone from bad to worse. There are more failed states and more armed non-state-actors and terrorist groups. The socioeconomic conditions that drove revolt almost a decade ago are generally worse than they were then. Also the repressive political conditions, and the absence of inclusive and responsive political institutions, are worse today than they were a decade ago. The regional disorder is also more acute, in that open warfare and conflict—once confined largely to Lebanon— have now spilled over into Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya.

There are a number of ways in which things could get considerably worse. Tensions between Iran and Israel or Iran and Saudi Arabia could escalate into all-out war. Egypt or Saudi Arabia could, for example, stumble and fall as other large states have in the recent past. Terrorist groups, pushed back in Iraq and Syria, could regroup and stage a major comeback either in another part of the region or through new methods of terrorist attack such as cyber warfare and weapons of mass destruction. Finally, deteriorating socioeconomic, political or environmental conditions could lead to another broad wave of protests and uprisings, and fresh waves of migration and refugee flows in the region.

Things Dramatically Improve

Given the number of negative factors that are self-inflicted in our region, it is not too farfetched to imagine that, with a sustained campaign of better policies, conditions in the region could improve. At the regional level, any significant transformation of the relationship between Iran and the region from one of conflict to one of de-escalation or even cooperation would have a transformative and positive effect on helping end civil wars, wind back radical sectarian groups, reduce wasteful spending on defense, and take advantage of numerous economic opportunities.

If Saudi Arabia and/or Egypt succeed in their ambitious economic and social plans and break through to high levels of growth and employment, that too could have a significant impact on raising living standards and relieving domestic pressures. If the three ongoing civil wars in Libya, Yemen, and Syria reach a sustainable negotiated settlement with regional and international buy¬in—and move toward stabilization and reconstruction—that too could have a broad positive effect on the region. The same can be said for Iraq’s attempt to build on its defeat of ISIS and its inclusive political system in charting a positive road forward in terms not only of security, but also of economic and political development.

On another level, it is not out of the question to imagine resurgent civic and political demands leading to a stepping back from full-scale authoritarianism and a re-appreciation of the wisdom of inclusive and responsive political systems. These systems could appear either in the form of democratizing republics or constitutional monarchies.

Although imagining a Middle East at peace with itself, interacting within an inclusive regional framework, and charting significant progress in ending civil wars, achieving significant economic development, and reclaiming the pathway toward more representative and democratic government might seem like a pipe dream, few in Europe in 1940 could have imagined the Europe of 1950, and few in East Asia in 1970 could have imagined the East Asia of 1990. Good things also happen.

Pivoting on the Positive

This positive pathway is important to consider, not only to see that it is within the realm of plausibility, but also to identify key elements which policymakers and opinion makers ought to promote and work toward. In brief, this would mean a focus on five main goals.

First, states need to work toward a de-escalation of regional tensions and the creation of a more cooperative regional framework; concomitantly, international powers should develop a more coordinated global approach to the Middle East. Second, regional and global actors should focus on finding a rapid and negotiated end to civil wars and begin helping with post-conflict stabilization and reconstruction. Third, leaders in the Arab World need to maintain a priority on economic reform, investment, and development, while providing sufficient protection for the poor. They must also work together to find regional strategies to confront challenges like climate change, aridity, and water shortages. Fourth, it is important to move away from the trend toward resurgent authoritarianism, in favor of broader civil-political rights, and more representative, inclusive, and responsive governments.

Perhaps a focus on these general policy pathways is an appropriate place to bring this summary exploration of possible Arab futures to a close. Future studies are always an exercise in exploration, not prediction; in identifying trends that policymakers need to be aware of; in appreciating the dangers and risks that might be coming down the road, and also identifying possible opportunities and positive outcomes. Future studies is a pivoting away from an obsession with the past and the fleeting present, to focus squarely on how we can work together to bring about a dramatically transformed and improved future akin to what other regions of the world have been able to create in the present.

Paul Salem is the Vice President for International Engagement. He served previously as MEI’s President and CEO. He is currently based in the Middle East and works on building partnerships throughout the region. His research focuses on issues of political change, transition, and conflict as well as the regional and international relations of the Middle East. Salem is a frequent commentator on US and international media, and is the author and editor of a number of books and reports including Escaping the Conflict Trap: Toward Ending Civil Wars in the Middle East (ed. with Ross Harrison, MEI 2019); Winning the Battle, Losing the War: Addressing the Conditions that Fuel Armed Non State Actors (ed. with Charles Lister, MEI 2019); From Chaos to Cooperation: Toward Regional Order in the Middle East (ed. with Ross Harrison, MEI 2017), Broken Orders: The Causes and Consequences of the Arab Uprisings (In Arabic, 2013), “Thinking Arab Futures: Drivers, scenarios, and strategic choices for the Arab World“, The Cairo Review Spring 2019; Bitter Legacy: Ideology and Politics in the Arab World (1994), and Conflict Resolution in the Arab World (ed., 1997). Prior to joining MEI, Salem was the founding director of the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, Lebanon between 2006 and 2013. From 1999 to 2006, he was director of the Fares Foundation and in 1989-1999 founded and directed the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, Lebanon’s leading public policy think tank. Salem is also a musician and composer of Arabic-Brazilian jazz. His music can be found on iTunes.

Read More