Trump versus Globalization

As a presidential candidate, Donald Trump campaigned on promises that would reverse years of trade liberalization. Whether or not he triggers a global trade war, his policies are undermining America’s standing as the preeminent world leader.

President-elect Donald Trump visiting a Carrier Corporation air conditioning factory, Indianapolis, Dec. 1, 2016. Evan Vucci/Associated Press

For the first time since 1930, trade became a high-profile issue in the U.S. elections in 2016 as the postwar consensus around the liberal order of global economic cooperation and openness seemed to unravel. Three underlying reasons can be identified: anemic growth in median household income since the turn of the century; continued loss of jobs in the manufacturing sector; and evident prosperity of the top 1 percent income bracket and Wall Street. It became all too easy to wrap these grievances into a “blame the foreigner” anti-globalization message, even though the sources of malaise were at home, not abroad. Automation and artificial intelligence have displaced far more jobs than imports, and the absence of a meaningful social safety net and adequate retraining programs have been features of American public policy for decades.

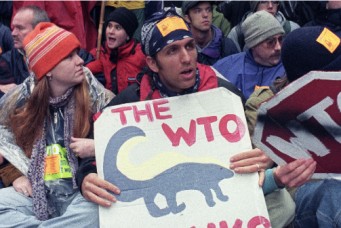

Rather than address the basic causes of the economic problems, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump advocated policies that would reverse years of trade liberalization and overturn the U.S.-led rules-based system. He threatened to unilaterally impose high tariffs on imports from major U.S. trading partners (China and Mexico), renegotiate or terminate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and even pull out of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The U.S. trade deficit, some $500 billion in 2016, along with alleged “unfair trade practices” of U.S. trading partners, were blamed for stunting the U.S. manufacturing sector and causing lost jobs and lower wages. Trump denounced U.S. companies like Ford, Nabisco, and Carrier for investing and producing overseas, and threatened to penalize offshoring decisions. His indictments made no economic sense but they contributed to Trump’s victory over Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in the November presidential election.

In her campaign, Clinton also criticized NAFTA and the TPP, but with less strident rhetoric than Trump. As First Lady in 1993, Clinton had been privately skeptical of NAFTA, which was ratified under her husband President Bill Clinton. Subsequently, in her 2008 campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, Clinton promised to overhaul the agreement, as did her rival, then-Senator Barack Obama. Senator Bernie Sanders, in competition with Clinton for the Democratic nomination in 2016, demonized NAFTA and the TPP, linking trade pacts to corporate greed, the top 1 percent, and Wall Street.

As a consequence of the common political front in the presidential campaign against trade pacts, U.S. trade policy is now constrained by bipartisan sentiment: in Congress, as many Democrats as Republicans oppose fresh liberalization and new international rules. These were popular themes in the 2016 campaign, good for stump speeches and rounding up votes. Anti-globalization sentiment will not disappear anytime soon.

This is unfortunate. Globalization and the expansion of international trade and investment have delivered enormous benefits to the U.S. economy. The expansion of global trade has been spurred by eight rounds of multilateral trade negotiations under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the WTO, and new regional pacts, such as the European Union, NAFTA, and other trade agreements that further deepened trade and investment liberalization. Meanwhile, technological advances in transportation and communications slashed economic distance between countries.

As a result, in the United States, trade as a share of GDP has more than tripled since 1960. Analysis shows that the U.S. economy is $2.1 trillion larger today (about 11 percent of gross domestic product) owing to globalization since World War II. Equally important, the huge payoff to any nation from participating in global commerce explains why so many countries have switched from command-and-control systems to market economy systems with freer trade. At the same time, the post-World War II period has been a golden era for U.S. leadership, with great success in promoting liberal economic policies and democratic politics. These achievements are now at risk, given President Trump’s agenda.

A serious problem is that along with increased economic openness, U.S. policy did not combine trade liberalization with a strong social safety net for workers who lose out, mostly from technology but also from globalization. Displaced workers have a hard time criticizing robots or automatic teller machines, but they can denounce imports from China or Mexico. Like its predecessors, the Trump administration shows little support for policies that might relieve the underlying economic anxiety of American workers and enable them to cope with change. One such policy would be “wage insurance” for workers who are displaced from their jobs through no personal fault, and subsequently accept a lower paid job. Wage insurance would compensate these workers, through public funds, for part of their lost wages for a defined period, say three years. But instead of constructive solutions, the Trump administration blames trade for a vastly disproportionate share of workplace woes.

The president has broad executive authority to impose barriers to imports and exports, along with international investment and financial flows. But, as research by the Peterson Institute for International Economics suggests, major trade restrictions would inevitably prompt foreign retaliation and significantly damage U.S. firms, costing millions of American workers their jobs. Drastic trade actions would disproportionately affect core Trump constituencies, namely blue collar workers and farming communities. Such actions would also risk confrontation with Congress, just as Trump seeks to build consensus for major domestic reforms related to corporate taxes, infrastructure, and healthcare. Congressional misgivings could serve as a check on major trade restrictions, at least in the near term. On the other hand, in the medium term, fiscal stimulus combined with tax cuts and a stronger dollar would contribute to larger trade deficits, increasing protectionist pressures—as happened during the Ronald Reagan administration (1981–89).

Since his election, Trump’s tone has moderated and actions have been less drastic than campaign threats. During his first hundred days in office, Trump withdrew the United States from the TPP, as he had promised, and he took the first steps toward launching a renegotiation of NAFTA. He signed several executive orders to bolster trade enforcement and initiated new investigations into U.S. imports of steel and aluminum products, hinting at similar investigations of copper and solar panels. Trump announced a 100-Day Action Plan with Chinese President Xi Jinping, committing Beijing to resolve certain trade disputes and facilitate greater U.S. exports. But Trump pulled back from his campaign rhetoric that denounced China as a “currency manipulator.” Most of these initiatives will not have an immediate impact on trade but could set the stage for changes during the next five years.

The Trump administration released its trade agenda in March 2017, based on the overarching goal of expanding “trade in a way that is freer and fairer for all Americans.” As operational guidelines, Trump seeks to reduce bilateral trade deficits (preferably by expanding U.S. exports but if necessary by contracting imports) and ensure that foreign barriers on specific U.S. exports are no higher than U.S. barriers on imports of the same products (“mirror-image reciprocity”).

Trump is particularly alarmed by U.S. bilateral trade deficits with five named countries (China, Mexico, Germany, Japan, and South Korea). However, in a world of multilateral trade flows, bilateral trade deficits do not illuminate win-win opportunities for trade liberalization. At best, they couple potential leverage with an implicit threat: “I’ll buy less from you unless you buy more from me.” Trump’s predilection for mirror-image reciprocity can only work, if at all, as a two-way proposition: the United States must be prepared to reduce its barriers on products that are out of line with its partners’ barriers. At a conceptual level, Trump’s operational guidelines do not provide a promising framework for trade negotiations.

Nevertheless, the Trump administration has announced four priorities to ensure a level playing field for U.S. companies and workers: defend U.S. national sovereignty; strictly enforce U.S. trade laws; use leverage to encourage other countries to open their markets to U.S. exports and enforce U.S. intellectual property rights; and negotiate new and better trade deals. To advance these priorities, Trump’s first one hundred days in office were marked by early actions on trade negotiations, executive orders, and “self-initiated” investigations into U.S. imports of dumped or subsidized products.

Trump Trade Negotiations

Trump pledged to reject multilateral trade deals and negotiate new bilateral deals “to promote American industry, protect American workers, and raise American wages.” Consistent with campaign promises, on January 23, 2017—his fourth day in office—Trump instructed the U.S. Trade Representative to withdraw the United States from the TPP, which was signed in February 2016 by the Obama administration after five years of negotiations, but not ratified by the U.S. Congress. The TPP mega-regional trade deal was negotiated between the United States and eleven countries in the Asia-Pacific, including Australia, Canada, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Vietnam, and others, which collectively account for more than one-third of global economic output. The TPP was lauded as the most comprehensive regional trade deal negotiated between developed and developing countries as it not only eliminates a broad array of barriers to trade and investment but also establishes new trade rules in innovative areas like digital trade and e-commerce, state-owned enterprises, and labor standards. Trump’s withdrawal from the TPP means foregoing economic benefits: the other eleven TPP partners promised substantial reductions in their barriers to U.S. exports of goods and services, and econometric estimates suggest that U.S. real income in 2025 would have been $131 billion higher per year, or 0.5 percent of GDP, owing to plurilateral liberalization.

Moreover, U.S. withdrawal from the TPP has undermined American credibility as a negotiating partner, and ceded to China and Japan erstwhile U.S. leadership in the dynamic Asia region just as initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, One Belt One Road Initiative, and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) move forward without U.S. participation. China is already a major trade and investment partner of countries in Asia and worldwide, and TPP countries are moving forward to deepen ties; Canada and Mexico are seeking to open talks with China while Chile, Australia, New Zealand, and Malaysia are seeking to expand existing deals, and seven of the original TPP-12 are participating in the RCEP talks. The other eleven TPP partners are exploring ratification of the pact among themselves, without the United States; if this happens, U.S. firms and workers will lose out on fresh opportunities and face new discrimination since tariffs and rules for trade between the eleven would be more favorable than those for trade with the United States.

Trump’s draft executive order in late April to terminate NAFTA entirely was quickly rescinded after he talked with President Enrique Peña Nieto of Mexico and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada. NAFTA was a contentious agreement from its inception, during the administration of President George H.W. Bush. In 1993, Bill Clinton had to twist the arms of his fellow Democrats to secure ratification by the House of Representatives, in a close 234–200 vote. The primary goal of NAFTA was to spur two-way trade between the United States and Mexico by eliminating tariffs, since the earlier Canada–U.S. free trade agreement had already eliminated most tariffs on America’s northern border. A secondary but related goal was to foster direct investment in Mexico. NAFTA succeeded on both counts: two-way goods trade between the United States and Mexico expanded from about $80 billion in 1993 to $240 billion ten years later. The stock of direct investment in Mexico—mainly by U.S. firms—leaped from $41 billion in 1993 to $163 billion in 2003. But U.S. opponents of NAFTA continued to blame the pact for creating job losses and depressed wages, even though the adverse effects were modest.

Candidate Trump promised to renegotiate NAFTA, which he called a “disaster” for perpetuating a bilateral trade deficit with Mexico and weakening the U.S. manufacturing sector. As president, he has also criticized specific Canadian trade practices, notably in the lumber and dairy industries. Serious economic analysis rejects the claim that NAFTA is responsible for the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico: there is simply no association between bilateral trade deficits and free trade agreements. More fundamentally, a bilateral trade deficit is no proof of economic disadvantage. Households incur bilateral deficits with their grocery stores, and bilateral surpluses with their employers, but these imbalances do not signal economic losses or gains. The same is true of trade imbalances between nations. The claim that NAFTA has weakened the U.S. manufacturing sector ignores the overwhelming impact of automation and information technology on manufacturing jobs, even though U.S. manufacturing output reaches new heights every decade. Trump is on stronger ground when he points to specific trade practices—for example, Canadian subsidies to its softwood lumber firms and dairy farmers—but in this traditional realm of trade policy he also needs to acknowledge longstanding U.S. trade barriers, for example restrictions on government procurement and coastal shipping.

Canada and Mexico strongly disagree with Trump’s negative characterization of NAFTA, but all three countries have concurred that the agreement can and should be modernized. Under U.S. law (the Trade Promotion Authority of 2015), the president must give ninety days notice to Congress before NAFTA talks can begin. A draft notice of U.S. negotiating objectives was circulated to Congress in March 2017, signaling priorities in the new negotiation. After Robert Lighthizer was confirmed as the new U.S. Trade Representative on May 11, he delivered the formal notice to Congress.

Most of Trump’s objectives for the new NAFTA talks are consistent with past practice. But a few goals expressed at times by Trump officials could derail the trade talks, foreshadowing a possible withdrawal from NAFTA by the United States. In particular, potential breaking points include strong demands on Mexico to eliminate its trade surplus with the United States, highly restrictive rules of origin in the automotive sector (no imports of parts from Thailand, China, Japan, or Korea), denial of access to government procurement contracts in favor of Buy America requirements, and “level the playing field” in tax treatment, a reference to Canadian and Mexican border tax adjustments for their goods and services tax and value added taxes, respectively.

Termination of NAFTA would entail a major setback in U.S. relations with its southern and northern neighbors, and would probably undermine cooperation on drug trafficking, illegal immigration from Central America, transit through the Arctic Ocean, and other issues. The economic dislocation from the termination of NAFTA would likely embitter an entire generation of Mexicans and Canadians.

On the other hand, modernization of NAFTA is a very different proposition, with potential benefits to all three countries. In updating NAFTA, the three trade negotiators can profitably draw from TPP chapters that addressed a range of new issues that were out of sight when NAFTA was ratified in 1993: digital commerce; state-owned enterprises; currency manipulation (a theoretical problem in North America, but a real problem elsewhere); defects in the investor–state dispute settlement framework; liberalization of Canadian agricultural barriers and U.S. cabotage rules; and stronger enforcement of labor and environmental standards.

A renegotiated NAFTA could in turn set the framework for engagement with other trading partners. Trump officials have suggested a revised U.S.–Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS), and new bilateral trade deals with Japan and even the United Kingdom. But these face major hurdles, namely Korea’s reticence to alter the terms of KORUS, Japan’s strong preference for the TPP rather than a Japan–U.S. bilateral trade agreement, and the UK’s pending Brexit negotiations with the European Union. More broadly, a bilateral approach to trade talks, premised on significant U.S. demands for concessions from trading partners without reciprocal concessions by the United States, seems unlikely to succeed.

Trump Executive Orders

On his own initiative, without asking for congressional assent or negotiating with foreign countries, Trump can issue executive orders that shape the direction of trade policy and, if he so decides, restrict U.S. imports or exports. Although he has ample statutory authority, Trump so far has not limited U.S. trade. But he has issued several executive orders that direct new reports, assessments, and policy proposals by the U.S. Trade Representative, Commerce Department, Customs and Border Patrol, and others, throughout much of 2017, with a view to tightening trade enforcement. A summary of major actions and their motivations:

Presidential Executive Order Regarding the Omnibus Report on Significant Trade Deficits (March 31, 2017). The order directs the Commerce Department to “assess the major causes of the trade deficit,” focusing on “unfair and discriminatory practices” of U.S. trading partners. But bilateral trade deficits make little economic sense as a guide to trade policy in the twenty-first century. Because the United States persistently spends more than it produces, it must borrow or attract investment from abroad, reflecting a low savings rate. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross claims that underlying the deficit is the fact that the “U.S. has the lowest tariff rates and the lowest non-tariff barriers of any developed country in the world.” However, as economist Joseph Gagnon has demonstrated, trade policy, reflected in tariffs and free trade agreements, has little impact on the overall trade balance. Rather, fiscal policy and currency intervention are far more important determinants. Economist Caroline Freund concludes: “The aggregate U.S. trade deficit may be of concern, but it should be considered in the context of macroeconomic not trade policy.” That said, the Omnibus Report will probably serve as the “wish list” for U.S. demands in forthcoming trade negotiations.

Presidential Executive Order on Buy American and Hire American (April 18, 2017). The order directs U.S. agencies to “scrupulously monitor, enforce, and comply with Buy American laws” including use of domestically produced iron, steel, and manufactured goods in public projects, and to minimize waivers and exceptions. The U.S. Trade Representative and Commerce Department are directed to evaluate whether U.S. free trade agreements and WTO commitments weaken or circumvent “Buy American” laws. The other half of the order relates to “Hire American” and mandates stricter enforcement of U.S. immigration laws and visa programs. While politically popular, “Buy American” can be economically costly, and the United States itself has long criticized the promotion of domestic content and other discriminatory “buy-local” policies by other countries.

Presidential Executive Order Addressing Trade Agreement Violations and Abuses (April 29, 2017). This order was motivated by the alleged failure of U.S. trade and investment agreements to “enhance our economic growth, contribute favorably to our balance of trade, and strengthen the American manufacturing base.” Within 180 days, an interagency effort led by the U.S. Trade Representative and the Commerce Department will conduct “performance reviews” of all bilateral and multilateral trade and investment agreements—including trade relations with countries in the WTO with which the U.S. does not have a free trade agreement and also runs a trade deficit. The United States already issues several reports of this nature, most prominently the annual, five-hundred-page National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, which highlights problems facing U.S. exports, foreign direct investment, and intellectual property rights. The new executive order could lead to demands for modifying WTO rules. Secretary Ross has claimed that “there has never been a systematic evaluation of what has been the impact of the WTO agreements on the country as an integrated whole.” As a presidential candidate, Trump questioned the value of participation in the WTO, threatening to withdraw the United States from membership.

Presidential Executive Order on Establishment of Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy (April 29, 2017). The order establishes a new office to be run by economist Peter Navarro, which will advise the president “on policies to increase economic growth, decrease the trade deficit, and strengthen the United States manufacturing and defense industrial bases” and serve as a liaison between the White House and the Commerce Department. The new office is directed to implement “Buy American” and “Hire American” policies in particular. It’s not clear how influential the new office will be in shaping U.S. trade policy.

Presidential Executive Order Establishing Enhanced Collection and Enforcement of Antidumping and Countervailing Duties and Violations of Trade and Customs Laws (March 31, 2017). The order is intended to rectify some $2.3 billion in uncollected antidumping and countervailing duties. This happens because the final AD/CVD duty assessed by Commerce can be higher than its initial estimate, leaving a balance due years later. Meanwhile, some importing companies have since gone out of business or were dissolved to avoid paying additional duties. The executive order requires the Department of Homeland Security, in consultation with the departments of Treasury and Commerce and the U.S. Trade Representative, to implement a plan to impose bonding requirements that better cover antidumping and countervailing duty liability for importers at higher risk of noncompliance. It also orders a new strategy to narrow violations of U.S. trade and customs laws.

More broadly, action against U.S. imports of goods dumped at unfairly low prices or subsidized by foreign governments—such as the recent imposition of preliminary countervailing duties against Canadian softwood lumber—is a Trump priority. The United States is already a major user of antidumping and countervailing duties, with nearly four hundred active orders in place. But the administration has pledged to ramp up “self-initiating trade cases, which speeds up the process of taking corrective action while allowing the Commerce Department to shield American businesses from retaliation.”

In the case of steel and aluminum, the Trump administration is invoking a far-reaching, and less commonly used, statute. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 permits an investigation by the Commerce Department regarding whether imports “threaten to impair” U.S. national security. The administration announced investigations for steel and aluminum as “critical elements of our manufacturing and defense industrial bases,” with instructions to Commerce to expedite the study. The national security exception, rarely used, faces little or no WTO scrutiny (owing to GATT Article XXI) and is thus hard to challenge. As economist Chad Bown cautions, “New import restrictions arising under that area of U.S. law really are akin to the ‘nuclear option’—their use really puts the entire system of international trade law at risk.”

U.S.-China 100-Day Action Plan (April 7, 2017). China is the single largest source of the U.S. trade deficit owing to its strong comparative advantage in a broad range of manufactured goods. China’s bilateral trade surplus was more than $300 billion in 2016, accounting for more than half of the U.S. global trade deficit of about $500 billion. This surplus, concentrated in sectors like computer hardware, cellphones, apparel and footwear, and steel coupled with China’s reluctance to open its markets to U.S. agriculture and service exports, have made China a pointed target of U.S. trade disputes over the past decade. In the 2016 presidential campaign, China thus became the object of severe criticism. Strident views were voiced by Ross and Navarro, who accused China of stealing intellectual property, dumping goods in the U.S. market, manipulating its currency, and unfairly restricting imports from the United States.

A comprehensive U.S.–China trade deal may be a distant reality, but managing bilateral frictions and improving the economic relationship remains crucial. The 100-Day Action Plan pledged to work toward “rebalancing trade.” On May 12, both sides issued a progress report on the U.S.–Chinese agreement highlighting, among other things, Chinese commitments to import U.S. beef, increase market access for U.S. credit rating and credit card services, and accelerate “science-based evaluations” of pending U.S. applications to export biotech products (such as genetically modified organisms). The agreement aims to resolve specific trade disputes to a limited extent; more importantly it signals the intent to work together to “avert a trade war.”

Lost Opportunities?

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power “to regulate Commerce with Foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes.” However, thanks to successive statutes stretching back a full century, prior congresses have given presidents ample power to restrict both trade and financial flows. To be sure, Congress is parsimonious when it comes to liberalizing trade. Liberalization requires a specific time-limited delegation of power, enabling the president to negotiate trade agreements (such as the Trade Promotion Authority of 2015), and the president’s handiwork must then be endorsed by congressional ratification of implementing legislation. But a president who wants to restrict trade enjoys almost carte blanche authority.

Just because Trump possesses the legal power to carry out his campaign declarations does not mean that a trade war is around the corner. Equally important are congressional considerations. Trump’s legislative priorities include repealing and replacing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, enacting corporate tax reform, and launching a massive infrastructure program. Such landmark measures can only be passed using the budget reconciliation process for the 2017 and 2018 budgets, thereby requiring just fifty-one Senate votes, not the sixty needed to overcome a filibuster by naysaying Democrats. Why would Trump muddy his priority agenda by starting a trade war, thereby infringing on congressional sensibilities, risking a global recession, and possibly losing the votes of traditional Republicans?

Even targeted trade restrictions will attract vigorous court challenges by affected U.S. business firms and possibly some states. Most of Trump’s actions would likely survive these challenges, both because he would have the constitutional foreign affairs powers of the presidency on his side and because he could cite multiple statutes giving him authority.

But foreign countries will not patiently wait for U.S. court proceedings or litigation in the WTO to vindicate their trading rights. Targeted retaliation is almost certain, and would be carefully crafted to hurt states, companies, and communities that count themselves as Trump supporters. For example, in the current softwood lumber dispute, Canada has quietly threatened to restrict imports of packaging materials from Oregon and not allow transshipment of coal from Wyoming and Montana. The larger the battlefield of trade conflicts, the greater the opening handed to China to lead the world trading system. This should not be a welcome outlook for Trump’s diplomatic and security advisors.

Trump will surely open aggressive NAFTA negotiations with Mexico and Canada, and put demands on China and South Korea. He has already dumped the TPP, and will likely shelve the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. His administration will initiate multiple antidumping and countervailing duty cases and probably disdain adverse WTO rulings. These actions bring no joy to free traders. Great opportunities for boosting the world economy and lifting American living standards will be lost. Globalization—reflected both in escalating trade-to-GDP ratios (annual trade in goods and services has reached nearly 60 percent of world GDP), and in the vast growth of foreign direct investment (the FDI stock is now 35 percent of world GDP)—has been a major driver of global prosperity since World War II. Despite contemporary discontent, the past seventy years have been the best period of comparable duration in world history.

Skepticism toward multilateral trade deals combined with more protectionist U.S. trade policy would stunt fresh policy liberalization at a time when the pace of global trade growth has been disappointing. Since 2008, the global economy has seen its longest period of relative trade stagnation due to a combination of sluggish global economic recovery, shorter supply chains, the lack of new liberalization, and rising micro-protectionism. The WTO projected a slight uptick in growth in 2017, but cautioned that policy uncertainty, namely the potential for restrictive trade policies and the uncertain outcome of Brexit talks, could undermine a rebound.

Whether world prosperity flourishes in the next decade is clearly an open question. But if Trump limits his actions to the measures so far announced, they will not bring the United States to the brink of a global trade war. At the same time, his policies are sure to diminish America’s standing as the preeminent global leader and undermine U.S. ability to influence the decisions of foreign leaders.

Gary Clyde Hufbauer is the Reginald Jones Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Previously, he was the Maurice R. Greenberg Chair and Director of Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Marcus Wallenberg Professor of International Finance Diplomacy and deputy director of the International Law Institute at Georgetown University. He served as deputy assistant secretary for international trade and investment policy at the U.S. Treasury from 1977 to 1980. He is the coauthor of Bridging the Pacific: Toward Free Trade and Investment between China and the United States; US-China Trade Disputes: Rising Tide, Rising Stakes; and NAFTA Revisited: Achievements and Challenges, among other works.

Cathleen Cimino-Isaacs is a research associate at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and manages the institute’s “Trade & Investment Policy Watch” blog. She is coeditor of Trans-Pacific Partnership: An Assessment and coauthor of Local Content Requirements: A Global Problem.