Turning Somalia Around

The rise of the jihadist Al-Shabab group has compounded Somalia’s problems with internal warlords and regional rivalries. Will a new constitution and elections in 2016 finally bring hope to this “failed state?”

Al-Shabab fighters, Mogadishu, Feb. 17, 2011. Mohamed Sheikh Nor/Associated Press.

Somalia has long been a byword for a failed state. Amid the civil war in the early 1990s, the central government ceased to exist. Apart from pockets of relative stability in the north (in Somaliland and in part of Puntland), the people of Somalia have been living in a perpetual state of crisis, struggling for daily survival under the constantly changing influences of warlords and clan militia leaders, corrupt temporary authorities, and brutal Islamists.

In 2012, hope finally arose for Somalis, with prospects to move away from state failure and onto a path of state building and stability. Under strong international pressure, the Somali political elite agreed on a provisional constitution and the formation of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS). This government has gained international recognition and funding and, supported by African Union troops, stands as the best chance Somalis have seen to achieve peace.

New faces hailing from the business community, civil society movement, and the diaspora took the helm. They included President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and federal parliament Speaker Mohamed Sheikh Osman Jawari, who came into power in 2012 following a surprise vote within the new parliament, that stalwarts of the Somali old guard were seen as sure to win. The year 2015 is viewed as a “make-or-break” year, given the transition timeline set in the provisional constitution that calls for the popular adoption of a final constitution and holding new elections across the country by 2016.

Yet, many Somalis and international partners have been losing confidence in the process. There have been three cabinet changes in three years, due to political infighting, primarily power struggles between the president and successive prime ministers, in the context of ongoing clan tensions. The current political settlement remains very fragile, and security conditions are dire. There are serious questions about whether peace efforts can withstand a serious escalation of the nation’s protracted crisis.

The Quest for Security

The most important change the Somali people expect from the current transition is better security. Large parts of Somalia are still outside government control and function under the threat of unsanctioned violence by non-state actors, rather than rule of law. Without doubt, the FGS is held in place because of the presence of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), currently the dominant military force in Somalia.

Current AMISOM strengths are authorized for just over twenty-two thousand; countries providing troops are Uganda, Burundi, Djibouti, Sierra Leone, Kenya, and Ethiopia. It is responsible for protecting Somali government institutions and is at the forefront of the military offensive to reclaim territories across south and central Somalia. In support of FGS forces, AMISOM has made significant advances in regaining territory from the Al-Shabab group, starting in Mogadishu, and in south and central Somalia, by the borders with Kenya and Ethiopia, the crucial port of Kismayo, and, most recently, the militant stronghold of Barawe.

The largest threat to security continues to come from Al-Shabab. The group has been on the defensive, but still controls major parts of Somali territory, mainly outside of urban areas (though it keeps a presence in them). Al-Shabab has successfully implemented its strategy of guerilla warfare with attacks on government and foreign targets across the country. It has also launched attacks outside Somalia, most notably on crowds watching the televised FIFA World Cup final in Kampala in 2010, the Westgate Shopping Mall killings in Nairobi in 2013, and the Garissa student massacre in 2015. These attacks are designed to prove that the group is a viable fighting organization, and to ensure a steady flow of support from jihadists and extremists in the Horn of Africa and foreign supporters. They also aim to demonstrate (successfully) the weakness of the Somali security apparatus and to undermine the international security presence. The capital Mogadishu itself is so vulnerable that Al-Shabab has managed to attack the presidential palace Villa Somalia and the parliament despite AMISOM protection. Al-Shabab has targeted the offices of the United Nations and other international organizations, hindering efforts to rebuild key Somali institutions.

The security environment also continues to be weakened by clan disputes and conflicting personal interests, involving corruption related to vast networks of patronage and fighting for financial gain. These tensions persist within various institutions, including the national army, the police, the security agencies and intelligence services, as well as various guard forces and sub-clan militias loosely aligned with the government.

Local militias have also been consolidating their influence, particularly in proximity to the Ethiopian and Kenyan borders, amid the lack of local government structures and central government presence. This influence has undermined the processes of forming new federal states and local administrations in areas where tensions with the federal government were already high.

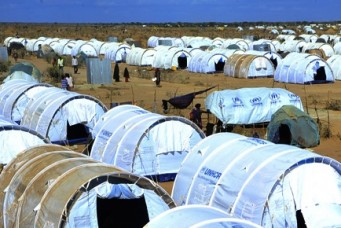

Somalia’s resilience has also been tested by a continuing humanitarian crisis. The question of food security persists in the country, which has endured famine on numerous occasions in the last twenty-five years. While the situation has improved since 2011, an estimated three million people remain in need of humanitarian assistance and more than eight hundred fifty thousand in need of emergency food supplies.

Somalia’s food security troubles are strongly rooted in the realities of conflict and lack of governance structures. The population keeps growing, with high birth rates, and experiences displacement due to ongoing fighting in the south and central parts of the country. People remain fragile to shocks, mainly from drought and floods, as local institutions don’t exist or are unable to cope with these problems. If food is scarce, food prices rise, and distribution patterns are abused—all showing lack of regulatory and security support.

The ongoing conflicts have crippled the Somali economy. Economic institutions are very weak. Somalia remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Gross domestic product per capita is about $300, annual internal revenues at only around $80 million. The key lines of income are from remittances (around $1.3 billion per year) and external economic aid (around $1 billion annually for all official development assistance).

The Islamist Factor

Political Islam is a relatively new phenomenon in Somalia. The religious identity has a variety of dimensions that have evolved during the era of state collapse and that now have a profound effect on the political process. Exploring these dimensions and taking them into consideration for policy and polity in Somalia is crucial for governance during the transition period and for bringing peace to the country.

The emergence and downfall of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) played a large role in shaping the current political scene in Somalia. The ICU was a group of sharia courts that temporarily created a rival administration to the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in 2006. Several conditions explain its rise: 1) Somalis identified with ICU’s commitment to Islam, which during decades of dire living conditions became a source of hope and strength; 2) ICU’s approach to government was close to what Somalis knew as the traditional justice system run by elders and local religious leaders; and 3) Somalia’s business community saw ICU as a potential bulwark of stability for commerce to resume.

ICU bolstered its position by temporarily bringing a rare degree of stability to south-central Somalia, primarily in Mogadishu. This came at the height of the U.S.-led “War on Terrorism”; fearful of growing extremism in the Horn of Africa, the United States (encouraged by the TFG) sponsored an Ethiopian invasion of Somalia to battle the forces of the ICU (which also had made revanchist provocations toward Ethiopia at the time). As the mainstream ICU was militarily weak, most of the defense came from their most well-organized fighting arm, Al-Shabab, whose young and energetic members had been hungry for a cause. These events split the ICU into several factions. Some joined the TFG forces they had fought against while other leaders split off to cling to regional power.

As a side result of the Ethiopian intervention, Al-Shabab won a popular reputation for defying a foreign invasion and gained an independent identity. Despite its brutal conduct in enforcing an extreme interpretation of sharia law, the population initially welcomed the organization for bringing some order and stability. The group has also been successful in raising resources. Al-Shabab has been particularly effective at playing on the political aspirations of smaller and less-privileged groups by forming alliances for territorial control and taking advantage of various sorts of taxation, including through charcoal exportation from the south and on road connections between cities and towns. The group also continues to receive funding from abroad, including from the Somali diaspora.

In the last few years, Al-Shabab attracted many recruits who enlist for financial gain (including many young men with no prospects in life), and more ideological jihadists who arrived from abroad to join their ranks. Yet, its ideology and politics do not have true support across Somalia. Civilians have become weary of Al-Shabab’s brutality and ultimate failure to govern. Al-Shabab’s popular support has faded, but moderate leadership among the clans has failed to fill the vacuum and forge stable and lasting governing structures where Al-Shabab had lost support.

An additional element in the development of political Islam in Somalia is the role and influence of groups emerging from the Muslim Brotherhood. President Mohamud and his closest allies come from Damul Jadiid (New Blood), a faction of Al-Islaah, which is the Muslim Brotherhood’s Somali wing. The group’s activities focused on promoting moderate Islamism; it has led one of the few successful drives for education and civil society activity in the war-battered country. These initiatives have created leaders, given Damul Jadiid a degree of credibility, and strengthened the footing for Islamism as a political movement in the peace- and state-building process in Somalia.

Damul Jadiid’s loose alignment with the Muslim Brotherhood has implications on Somali politics in the broader region. The current government continues to strengthen relations with the Islamist government of Turkey, and to receive resources from Qatar, known supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. It is also important to note that while 2012 brought fresh hope for a state-building process, a drive for secularization did not come with it. On the contrary, many of Somalia’s leaders favor political Islam, indicating that it will be the dominant ideology for the foreseeable future.

Perils of Foreign Involvement

External forces have staged significant interventions in Somalia over the last two decades. On a number of occasions, outpourings of humanitarian support have helped save many Somali lives, such as the first U.S. intervention in 1992 in support of the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM). However, too much interference in the political process and numerous international mistakes in developmental and humanitarian attempts have also fueled clan conflict. These included shortsighted policies such as backing different warlords in the 1990s. The U.S. misinterpretation of its role in Somalia amounting to forced intervention eventually led to the Black Hawk Down episode, deaths of U.S. soldiers, and the American retreat from the country. America’s enabling of the Ethiopian military intervention, furthermore, helped put Somalia into the hands of extremists.

Following these failures and collapse of state institutions, for many years international actors treated Somalia as a hopeless case. It took several mediation processes, transitional governments and road maps, and joint initiatives from the United States, Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) countries, and European countries to reach the 2012 political settlement. Somalia’s adoption of the provisional constitution and the selection of a new government in 2012 won the country new international confidence. Many conferences and meetings on the Somalia issue, in London, Brussels, and elsewhere, have attracted leaders from around the world. Western governments (including the United States) officially recognized a Somali government for the first time in two decades. These commitments to Somalia’s transition process have been translated into an agreement called the New Deal Compact, adopted in September 2013. The breakthrough document outlines a path for prioritization and coordination in state building and achieving a peace settlement, and has a financial pledge attached of almost $2.5 billion.

Progress toward implementation of the compact has been slow. Somalis and international experts have questioned whether an international template rather than a Somali-grown and -owned process is the most appropriate to guide the federal government and to meaningfully address root causes of the conflict. The ultimate implementation plans will most likely be last-minute elite compromises, limiting popular buy-in and broad stakeholder consultation. Meanwhile, frustrations with the process are building in the international community, mainly due to Somali inability to agree and work together.

Many Somalis in turn question the sincerity of the international community’s promises and its ability to deliver on them. In fact, containment seems to be the international default policy—global actors are primarily interested in making Somalia stable enough to prevent the return to widespread fighting and the growth of extremism. There is little political will to go beyond that containment by investing enough resources (including political, diplomatic, and human) to truly focus on growth, development, and setting a better governing environment for Somalis taking the helm.

Geopolitics has been a blessing and a curse for Somalia. The country has the longest coastline in Africa, with direct access to the world’s key shipping and trade routes through the Gulf of Aden. The territorial waters carry enormous fishing capacity and the potential for offshore oil and other resources. Access to the Indian Ocean, as well as potential trade routes to the modernizing and growing populations of central and eastern Africa, all create prospects for economic development. All of this could one day benefit a strong country on the path to development.

But these factors are also considered potential threats by Somalia’s neighbors, particularly Kenya and Ethiopia. These countries have deeply rooted interests in the shaping of the Somali state and the direction of its political process. As a result, these governments constantly seek to influence political development in Somalia, including the establishment of border militias, often contrary to Somali state-building interests. This is strongly linked to the historical background of the Ogaden War of 1977–78 when the Mohammed Siad Barre regime switched its allegiance to the United States and the West and attacked Ethiopia.

Somalia’s attempt to take over Somali ethnic territory in neighboring countries still casts a shadow over its relations in the Horn of Africa. Large Somali populations and swaths of ethnic Somali territories in Ethiopia and Kenya are constant sources of concern and increasingly identified as internal security threats. Somalia’s neighbors know that without a viable Somali state they will not be able to contain extremism in the region; on the other hand, they don’t want Somalia to become too strong in the future. The ultimate policy of Somalia’s neighbors will strongly influence the course of political development in Somalia.

Power-Sharing 4.5

The Somalia case is unique among other conflicts in Africa as it is driven neither by ethnicity nor religion. Nor is it underpinned by ideology. Somalis are people who mix traditional African, nomadic, pastoral, and Islamic cultures and despite decades of dire conditions, they are good humored, proud, and resilient. Yet when Somalis search for a unifying identity, their allegiances are being manipulated for political power and financial gains from clan, militia, and other political leaders. Somali federal authorities publicly condemn the manipulation, and profess a strong Somali national identity as their goal, but accept it for everyday political purposes.

Clan allegiance, which underlines both the social and political fabric of Somalia, arguably remains a force that blocks change and peaceful development. In an environment with little opportunity for financial gains and development, holding power is equated with personal gain, and perceived as such across the political leadership. The main method of conflict management between the Somali clans is the so-called 4.5 Clan Power-Sharing Formula (formally first defined during a national reconciliation conference in 1996–97). The 4.5 refers to the four major Somali clans (Rahanweyn, Dir, Hawiye, and Darood) and the additional 0.5 refers to space allocated for minorities. This breakdown determines the distribution of positions in government and political institutions. Seats in legislature are assigned based on this formula and it also serves as the unwritten rule used to balance civil servants compositions across ministries.

Since its adoption, the formula has remained central to political governance in Somalia. Supporters point out that while the formula may be imperfect, it has allowed for a broad consensus among clans, paving the way for many deals and preventing major clan warfare as seen in the early years of the conflict. Yet the formula has provoked major controversies. It has been labeled as contrary to the principles of democracy and an obstacle to free, fair, and transparent elections. Many politicians, community leaders, intellectuals, and academics have dismissed it as ineffective due to its inability to prevent recurring violent clan disputes. The governments formed after the adoption of the 2012 provisional constitution (and election of the current federal parliament) were established on the basis of the formula despite the constitution’s vision of politics based on policy and merit rather than clan allegiance. The realities on the ground show that this vision is still a distant prospect.

Several short-lived peace agreements of the past fifteen years have shown the inability to sustain compromises and address conflict root causes. The lack of political will for compromise results from the characteristics of the Somali political elites. Being a political leader in Somalia is a balancing act between clan identity and allegiance, armed groups and warlords, and external influences, as well as ability to create financial gains for personal (and closest constituency) interest. Somali elites have become very resourceful and extremely skilled in playing this game, Machiavellian at its heart. But often they display a stunning tendency to outmaneuver themselves, with their inability to share power. It creates a need for constant manipulation and preventing agreements necessary for the early stages of reconstructing the Somali state. These elites may win short-term gains, but the people they represent, and prospects for stabilizing and developing Somalia, are victims of the system.

2016 and Beyond

To achieve the promise of the 2012 agreement, Somalis must take strong measures to address security, justice, governance, economic, and ultimately political issues that hinder progress, the majority of which will need to take root primarily at the local level to succeed.

The dominant role of local militias in many areas clearly shows that the security strategy must be aligned with a strong push for political agreements in territories where new local authorities can be established following AMISOM’s military offensive. This means not only prioritizing a “stabilization” policy in reestablishing security and territorial control, but putting much more emphasis on advancing political settlements ensuring rapid establishment of local government. That approach should also form the core of the strategy to defeat Al-Shabab.

The fact that extremists continue attracting support in Somalia cannot be ignored in exploring political solutions to the conflict, especially in considering the need to develop political parties and groups that can accommodate some of the conservative Islamist politicians into the political mainstream. Al-Shabab cannot be eradicated solely through security operations—a political process that will consider elements of political Islam to be paired with the “stabilization” policy will be key.

A similar effort must be made with the economy. One of the economy’s few successes is livestock production (mainly in the north). Somalia has developed mobile banking (out of necessity, as no banks exist) and telecommunications systems. However, for Somalis to buy into the political transition, they must see “peace and stability dividends”—change in the form of job creation, basic livelihood improvement, and the production and trade of goods. In particular, if careful attention is paid to farming and the livestock export business, these areas can experience quick, bolstering improvements—especially when local-level investments are made.

Standing up local governments is also essential for Somalia’s progress in delivering services and relief to stranded populations. Traditional mechanisms such as councils of elders (gurti) can play important roles. Civil society organizations such as women’s associations, youth groups, religious organizations, and other local groups should be engaged to fill gaps while institutions are being established. Because these groups already have community trust, they can be valuable in defining community priorities, resolving disputes, and making resource allocation decisions. Building viable local governments will also mean relying on the traditional Somali system of governance called xeer, which consists of contractual agreements and customary laws that define the rights and responsibilities of an individual in relationship to his or her family, neighborhood, and clan. Balancing traditional rules and customs with new government initiatives through community institutions can lead to improved service delivery at the most basic level. And it will be crucial for delivering some visible change to the lives of people on the ground.

Today, more than 70 percent of Somalis are under the age of 30. Yet prospects for good education and employment are bleak; and moreover, these seem to be secondary issues for Somalia’s political leaders. Inspiring a new generation of leaders could be an important catalyst for change. Despite increasing attempts by young activists to participate in the political sphere, members of the country’s old generation continue to hold a majority of the key positions of power. The risk in marginalizing the youth is clear: without political outlets or livelihoods, young people are ripe for recruitment by local militias and extremist groups.

For local governments and economies to grow, mechanisms for justice and arbitration must be developed. Establishing a justice system is complicated in the Somali context due to the parallel existence of a secular law system, sharia law, and the xeer system—the traditional method of resolving disputes with the help of clan elders. Combining this with modern approaches to allow for better dispute management, increased trust in the judicial system, and the application of a written law remains the challenge. It’s a process that will take time and require compromises. Still, progress for indigenous state building will occur as populations (and businesses) put trust in hybrid judicial mechanisms and experience a gradual decrease of corruption and impunity.

Questions about post-conflict reconciliation and war grievances hinder Somali social cohesion, and need to be taken into consideration in the formation of local and regional policies. While justice and reconciliation processes are very important in a transition from civil war, they cannot be seen in Somalia through Western models and understanding of peace and justice. Even though a Truth and Reconciliation Commission was envisioned in the 2012 provisional constitution, the process of establishing the commission has not even started, and is generally seen by Somalis as an instrument imposed by the West. To quote a prominent Somali politician, elder, and scholar: “Somalia needs not truth and reconciliation, but forgiveness and conciliation, and this will appear closer to traditions of the society.” In the Somali context this approach is strongly linked to the reestablishment of local government, which will require compromise among groups who have fought sometimes for decades. A governance model also needs to identify spaces for thousands of citizens (many very young) who know only fighting as a way of making a living and need a new role in their lives. Traditional consensus building and cross-clan elder support can help achieve these steps. These mechanisms should be preserved and woven into permanent structures of governance, allowing for the quickest integration of societies.

The Challenge of Governance

Creating a sustainable governing structure is the key to escaping Somalia’s vicious circle of state failure. The adoption of a federal constitution through popular vote would amount to a peace agreement that could end decades of turmoil. But there are many obstacles in the way.

The process needs to include agreements on power sharing between state and federal authority. This comprises allocation of natural resources, resolutions to questions regarding federal and state tax income, and an outline of an electoral system that will establish future political authority.

The provisional constitution mandates that institutions reach agreements on some of the most contentious issues facing Somalis, but provides only general guidance on how to achieve this. This has proven to be a major obstacle; disputes are ongoing among key political actors on institutional prerogatives.

Apart from political elite deal making, the process of finalizing a revised constitution should arise from participatory political agreements and be at the center of a national dialogue that can lead to a strong mandate. Achieving broad and fair representation in the process is a major challenge. It is not clear which groups will be granted representation in a national dialogue, and agreement on representation will be difficult given the tight mandated timelines. While implementation of the constitution is a priority, it needs to be a central component of a broader peace process that adjusts to the realities of gradual agreements and settlements.

Among those in the Somali political class, the concept of a federal Somalia has been discussed extensively over the years and remains the preferred solution for shaping the future state. Most players agree that this power-sharing model can best accommodate all the diverse regional and clan interests. However, federalism itself is a puzzle to many Somalis—it raises as many negative feelings as positive ones. Many argue that federalism is a foreign concept, unknown to Somalia, and that a federal Somalia would be much weaker than a unitary nation. These critics argue that the federal states will be at the mercy of more powerful regional actors and their proxy militias, allowing external influences on Somali affairs to persist, and could be a breeding ground for more internal infighting.

The federal government’s first priority is to form federal units, to represent various interests throughout the constitution-making process leading up to elections by 2016. Several processes have been ongoing (in the Jubas, in Bay-Bakool, Galmudug), with various degrees of progress and success, marred by political crises.

Within these circumstances, debates continue around the extent to which the creation of the federal member states should come from a bottom-up process—driven by local communities, clan elders, and local authorities—or a top-down process driven by the federal government.

Timing is also a factor. Federations are not born in days, but develop over decades. Yet Somalia cannot afford to wait, since a federal structure providing fair representation is essential to the shaping of a final federal constitution. Currently, there is only one functioning state: Puntland. As such, it plays a key role in reaching agreements on formation of other states, future elections, and the political process for reviewing the provisional constitution. Puntland’s relations with Mogadishu are central to achieving these agreements, yet they remain difficult.

Elections could be a key step in legitimizing Somalia’s new political system, but its hard to see how the government can enable safe and secure voting across the country for “one man one vote.” Somalia is far from establishing an electoral system, an electoral commission, and viable political parties governed by laws. The absence of organized federal structures also prevents agreement on an election system by all potential representatives. Some hybrid systems including selection rather than direct election, or different voting methods in different territories, are being debated.

The likelihood of missing the 2016 deadline for holding elections has sparked a new political crisis, with strong suspicion the president is seeking automatic term extension beyond current mandate. Whatever the outcome of the electoral dispute, progress in changing the politics of Somalia will require a more participatory process for establishing political authority—and eventually a vote across the whole country.

Keys to Moving Forward

The adoption of the provisional constitution in 2012 and the signing of the New Deal Compact in 2013 were steps in the right direction, yet the progress still needed is enormous. To many, Somalia continues to be an unreliable state on the brink of total collapse. If peaceful developments are to occur, key change factors are needed for policy and political processes. These are changes that will ensure checks and balances, and will mitigate the risks of reverting to a collapsed state. They would also add momentum and political will to move Somalia out of perpetual crisis.

Creating a critical mass for political consensus. Given the complex web of interests and parties, it will be extremely difficult to gather sufficient political backing for a common agenda. The existing power divisions also make clear that it is highly unlikely that one group can emerge with enough influence to dominate the others and take the political helm.

What is required is a sustained attempt to create a critical mass of political will, converging interests toward the success of key policy decisions. There must be a strong consensus to advance the processes agreed upon in the provisional constitution, to find agreements with enough support, and to push through the stages of implementation. Importantly, this critical mass for progress has to be sustained in time to block potential crises and attempts at hindering the process.

This means finding commonalities among the interests of various parties and agreeing to make compromises. It could involve much stronger international pressure. It could require larger media campaigns aimed at rallying popular support, and building coalitions and agreements to isolate those obstructing progress. As momentum for changes occurs, all involved players must redouble their efforts to make deals in a comprehensive and inclusive manner that will eventually lead to strong backing for a peace settlement with agreements on power sharing and state structure.

Rethinking clan politics. Clan identity and boundaries of territorial influence are defining factors of Somali politics. Though enshrined in Somali history and culture, the clan system may also be the largest obstacle to escaping the current cycle of state failure. Breaking down clan barriers will be a key element in building a critical mass for political consensus. As Somalia considers change factors for the next generation, a consensus to start rethinking the role of the clan in social and political life will be required. This in turn entails strengthening the Somali national identity.

Renewing approaches to international and regional interests. Somalia strongly relies on external assistance for the execution of core state functions. It is clear that Horn of Africa regional politics and broader international considerations influence events on the ground, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Given the significance and high stakes of international involvement in Somalia, one could argue that a renewed and recharged approach is needed. Signing the New Deal Compact with donor governments was an important step that created a blueprint, but achieving its goals is nearly impossible in the timeframes proposed. In order to change that, much more political will would be required from external actors, to leverage more pressure for progress. Also needed are increased investments in security and operational conditions for the federal government and its international partners; this could take the form of more fortified central perimeters for key institutions—a “green zone”—along with an increased engagement of intelligence and special operations in support of securing Mogadishu.

The renewed international approach should include a long-term political engagement strategy, based on an immediately increased political and resource investment. The strategy should be viewed as a geopolitical investment into a strategically positioned country that can become a useful ally. This approach could benefit objectives of many states, including the United States, United Kingdom, as well as other countries of the European Union, Turkey, and the Gulf states. This would be a marked shift from the current policy of containment and troubleshooting and would be enormously beneficial to the growth and development of Somalia.

In addition, a renewed regional approach to political engagement is needed in East Africa. The key external players in Somali politics are the countries of IGAD, an eight-nation trading bloc. Frequently, IGAD’s policies are not in the best interest of Somalia. A smart international political approach must take the interests of these countries into consideration. Some security and border guaranties could be made, in exchange for a shift of policies allowing Somalia to stabilize and develop. In essence, this would be a political decision to shift from a policy of containment to a policy of opportunism and accelerated progression that can yield better results both for the country’s development and for achieving true progress in the fight against extremism and terrorism.

Searching for leaders. In order to eliminate individual as well as group and clan corruption on all levels of political and society relations, an individual commitment to change must come first. Somalis deserve to have leaders who can rise above personal and temporary interests for the sake of directing the country on a path away from state failure and toward stability and growth. Many countries that emerged from deadly conflict did so with the guidance of powerful central leaders. In Somalia, this is essential.

Leaders with enough charisma to grasp hearts and minds must convince people of the sacrifices and patience needed to create change. They must reach a hand through clan divisions. Such leaders can garner a true following and help foster political agreements. Somalia has not seen leaders of such stature, but history shows it is transformational moments like the one Somalia is experiencing that sometimes create them. At the same time, a spirit of responsible leadership has to spread among the hundreds of individuals in positions of influence and authority. Everyday leaders, the silent heroes, who shy away from personal gain first, can promote the process of building institutions and managing disputes peacefully; in turn, they can be an example for grooming the next generation of leaders. It is time for Somali change champions to step forward. Without visionary political acts and previously unheard-of progress in achieving political consensus among Somalis, it may be impossible to break out of the cycle of crisis.

Marcin Buzanski is a principal at the IGD Group. Previously, he was the project manager coordinating the Inclusive Political Process support project in Somalia for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) from 2012 to 2014. He was a crisis governance and state-building consultant with UNDP headquarters from 2010 to 2012, supporting programs in Africa, the Middle East, and South and East Asia. He has also served as a consultant with the United Nations and UNDP in Afghanistan, South Sudan, Liberia, and Kazakhstan and worked for the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) from 2004 to 2007.