Why Climate Journalism Must be Mainstreamed in the Arab World

While the issue of climate change journalism is particularly relevant to the Arab World today, as the upcoming COP27 and COP28 will be hosted in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates respectively, climate reporting in the region still lacks a critical lens that reflects the issue’s urgency

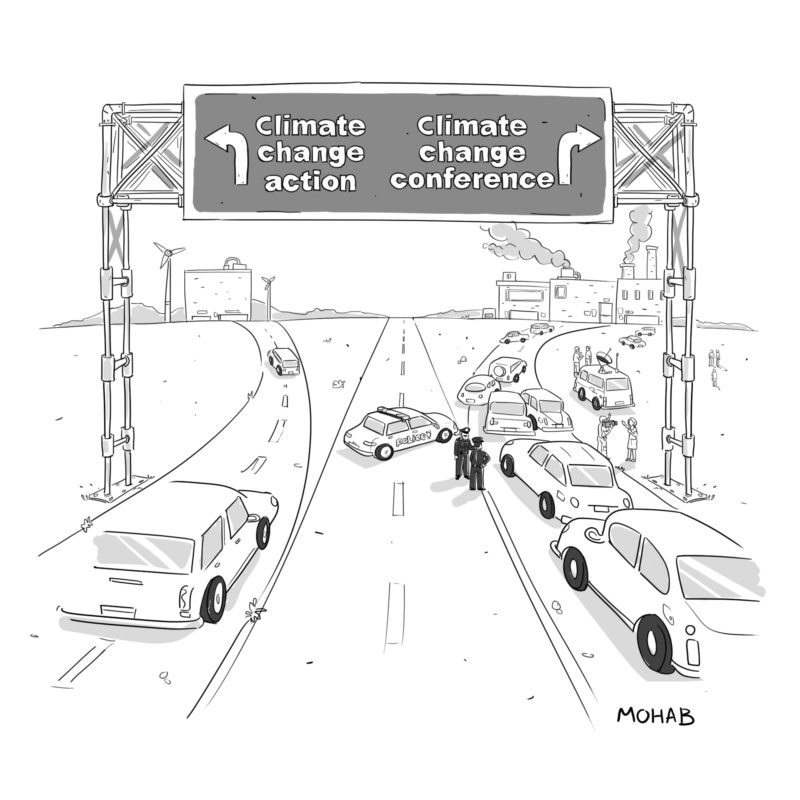

Illustration by Mohab Abdelfattah

In May, The New York Times Magazine published a story on the guilty plea of environmental activist Joseph Mahmoud Dibee for his role in a series of arson attacks organized by the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The group, later labeled as domestic terrorists in the United States, was founded in the United Kingdom in 1992. Their modus operandi was to destroy economic and infrastructural symbols of environmental degradation. Having emigrated from Syria to the United States as a boy, Dibee had been motivated early in his life by deforestation taking place close to his adopted home. After his indictment in 2006, he fled the country, only to be picked up in Havana and handed over to the U.S. authorities in 2018. What makes this story particularly compelling is its optics in today’s uncertain environment. As author Matthew Wolfe puts it, “climate change, no longer an abstraction, has begun to transform American life in the form of heat, fire, floods and smoke.” Wolfe argues that the story of the ELF and Dibee’s role in the actions perpetrated by the organization “may sound different to some listeners now than when prosecutors first told it”.

Indeed, the conversation around climate change is not what it was in the 1990s or even the early 2000s. The clock seems to be running out on the shadowy, fossil fuel industry-funded world of climate denialism. In the United States at least, the beginning of the end of this era perhaps occurred in 2009 when a 1995 internal document from the ironically named Global Climate Coalition, a lobbyist group tied to the fossil fuel industry, was revealed. The document indicated that the coalition’s own experts had shared the irrefutability of the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions with industry members, who concealed the information. While steeped in nebulous language, the report stated that “the scientific basis for the Greenhouse Effect and the potential impact of human emissions of greenhouse gases such as CO2 on climate is well established and cannot be denied.”

However, carbon-emitting industries continue to have massive political sway despite the public’s patience for greenwashing and deception having been exhausted. During COP26 in Glasgow, for example, the fossil fuel industry had the single largest delegation, with more than 500 industry representatives taking part. More recent examples of corporate deviance have included the revelation that the concept of the carbon footprint was introduced at the behest of fossil fuel companies to transfer blame from the corporations to the individual. This maneuvering and deception by corporate interests and government complacency with respect to the urgency of the crisis, coupled with the very real consequences of our warming planet, have sparked outrage and fear, and simultaneously altered the terms by which climate change specifically, and the environment in general, are discussed.

While in the West, conversations around the environment and climate change have long been taking place and have gone through many permutations, the dynamics of reporting on these topics in the Arab region are beholden to a vastly different political, cultural, and socioeconomic context. In his 2017 article “Climate Change Communication in Middle East and Arab Countries”, published in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science, Mikkel Fugl Eskjær writes that while the region is heterogeneous in terms of resources, socioeconomic conditions, and political priorities, shared conditions and similar government-controlled media systems have resulted in a relatively uniform approach to covering climate change and environmental issues in the region. Eskjær and others articulate that the majority of climate coverage encompasses protocol news or nearly verbatim publishing of official statements. “There is little if any critical journalism about official climate change policies, including national strategies in climate change negotiations,” Eskjær writes. And often, there is no coverage at all.

Meanwhile, scholar and broadcaster Nadia Rahman writes in her chapter in the Routledge Handbook on Environmental Journalism that environmental issues are relegated to the back of the list of priorities by news organizations in much of the region. “Most people in the Arab world are preoccupied with earning a living, safety, education, freedom, social justice, and development,” she writes, “the environment is often an after-thought.” While citizens are beginning to feel the effects of climate change impacting their lives and livelihoods, there are no systematic examinations of public awareness of climate change in the Arab region.

Despite the changing narrative around climate change and the environment, it is little surprise, given political and economic interests, that environmental journalists have faced challenges in reporting. Despite the existential nature of this crisis, decisive and comprehensive political action on climate has been continuously blocked or diminished, in large part due to the lack of popular support for concrete measures, such as increasing taxes on high-emission goods and services. We need only glance at the response to soaring gas prices from the war in Ukraine to see that when more immediate crises take hold, climate action, and with it tolerance for environmental reporting, takes a backseat.

The changing perception around Dibee’s story illustrates how the urgency of the climate crisis has transformed the narrative. It also hints at another point: that the line between journalism and activism, while in theory well defined, is often blurred—if not in the eyes of journalists themselves, then in the eyes of those for whom the story is costly. Pulitzer Prize-winning media scholar Eric Freedman writes in a 2020 article published in the Journal of Human Rights that the “boundaries between activism and journalism, even as practiced by trained professionals, are not always clear.” Freedman, whose article outlines the heightened risk of murder, arrest, lawsuits or other threats to journalists covering the environment, points out that the medium and location of coverage also impact where the line between journalism and activism falls. “Scholars and journalism professionals have long acknowledged that ethics standards, expectations, and on-the-ground realities differ from country to country and from time to time,” Freedman writes. It is of course necessary to note here that any blurring of those lines often carries different types of risk in the Arab region, where by and large, tolerance for activism tends to be low.

In recent years, the extent of the risks associated with environmental reporting have been increasingly brought to light. In a 2020 article for the Century Foundation, Peter Schwartzstein, an environmental journalist who regularly reports on the Arab region, details the risks of harassment, violence, and even death for reporters working on this beat. Schwartzstein cites the increasingly political nature of environmental reporting as the reason for the backlash. “Environmental reporting is more important than ever—for economies, societies, and peace and stability,” Shwartzstein writes, “but precisely because speaking the truth about the environment is increasingly and unavoidably political, governments and powerful businesses are fighting coverage of this decline like never before.”

A 2015 Reporters Without Borders report, “Hostile Climate for Environmental Journalists,” includes an account by Egyptian journalist Abeer Saady, who was beaten up by thugs hired by the factories she was investigating for dumping toxic waste into the Nile. Saady, whose career has spanned several decades and who reported on the wars in Iraq and Syria, said that her greatest difficulties arose when she decided to report on pollution.

As Egypt gears up to host COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh in November, and with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) set to host COP28 in 2023, the conversation around climate change, at least for the next two years, has landed squarely in the Arab region. This is a shift in attention for several Arab states, many of whom rely heavily on fossil fuel revenues. The UAE, notably, neglected to send their most senior officials to COP26 in Glasgow.

The Arab World is characterized most commonly by dry heat and desert, and for this reason, among other socioeconomic and political reasons, is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. According to UNICEF, the region has ten out of the seventeen most water-stressed countries globally.

In the lead-up to November, Egypt has been working overtime to prepare, promoting its sustainability projects and kicking regional collaboration efforts into high gear. For several years, Egypt has been working on increasing sustainability efforts and sources of renewable energy. The 2035 Integrated Sustainable Energy Strategy, unveiled in 2019, outlines intentions to increase renewable energy generation to 20 percent by this year, and 42 percent by 2035. Egypt has also announced multifaceted cooperation with other African countries and the African Development Bank, among others.

As the conference draws nearer, reporting on environmental and climate issues in the region has increased substantially, particularly in Egypt. This focus is a departure from the usual dearth of environmental journalism in the region; however, its content has not tended to deviate from the status quo, with virtually all coverage consisting of official statements on meetings and activities around climate cooperation. This has included, for example, climate-related cooperation within Africa, with China, as well as details about the many COP-adjacent initiatives currently underway.

In truth, the extent of the risks for environmental and climate journalists in the Arab region are unclear, given the lack of prioritization of these topics in the media. In their inaugural 2008 report, “Arab Environment: Future Challenges,” the Arab Forum for Environment and Development found that only 1 percent of Arab news programs focused on environmental news and less than 10 percent of newspapers employed an environment editor. Given the reduced budgets allocated to scientific topics in the years since this report, it is unlikely these numbers have increased in any meaningful way.

The hosting of COP27 and COP28 in the Middle East presents an opportunity to change how climate change and the environment in general are covered in the region. Eskjær points out that most editorials and op-eds on climate change published in the Middle East reflect international news and quote international sources, and thus do not necessarily speak to a local audience, nor reflect meaningful public engagement on the topic. This lack of locally focused reporting may be interpreted as “a token of how climate change still has not become integrated into the cultural vocabulary the same way as in Western media,” he writes. This, however, is an undeniably temporary state of affairs, as the direct effects of climate change on populations everywhere are becoming increasingly salient. More than ten years ago, the World Bank found that populations blamed extreme weather events for the loss of income, crops, and livestock in half-a-dozen Arab countries. Still, for the general population, the link between these experiences and the reality of climate change seems to be fairly weak, although not yet quantified. Reporting on COP27 and 28 in meaningful, relevant ways is likely to change this, at least in part.

Scholar Marwa Daoudy, who focuses on climate security in the region, writes that “no one should downplay the importance of climate change in today’s Middle East or the region’s future.” Daoudy argues that “policymakers must also understand that the worst outcomes related to environmental stress and scarcity in the region are not caused by long-term shifts in the climate, which are difficult to control, but by short-term choices made and actions taken by powerful people and institutions, which are far easier to influence.” In other words, poor governance and a myopic, self-interested outlook will have the largest negative effect on the environment and social stability, despite being easier to control than larger climate-related phenomena. This gives further credence to the important role of environmental journalism in shedding light on these practices to combat greed and complacency.

This sentiment is particularly relevant in the Arab World, because, unlike many of the other entrenched issues the region has long faced, there has, above all, been under-reporting on environmental issues. Increased space should be created for local journalists to report on environmental and climate-related issues that impact society. Such issues should not only be important in terms of setting the news agenda to reflect local circumstances and from local perspectives, but also for ensuring local populations are informed about the risks and challenges moving forward as we increasingly face the consequences of a warming planet. This will require the development and implementation of clear and transparent media laws relating specifically to environmental and climate reporting. It will require protections for journalists reporting on industrial malpractice, and increased access to environmental data, which tends to be held closely by governments in the region. And, finally, it will require investment in training journalists to report on these issues in an informed and balanced way.

The global conversation around climate change is evolving, and now is the opportunity to determine what that conversation looks like from the Arab World. After all, we have seen how denial and ambiguity have backfired in climate conversations elsewhere. Scholars and analysts have already partially attributed unrest and conflict in the region to the effects of climate change, some have even linked it to potential growth in militancy and terrorism. Avoiding the fulfillment of these ominous predictions must take place through local and regional cooperation, and by equipping populations with the information they need to manage and adapt to the changing climate through professional, rigorous journalism.

Sarah El-Shaarawi is managing editor of the journal Arab Media & Society and a contributing editor at Africa Is a Country. She is a founding coordinator of the Arab Science Journalism Forum. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications including Foreign Policy, Newsweek Middle East, The National, and Stranger’s Guide, among others. She is also the winner of the 2022 Dalton Camp essay prize. On Twitter: @SarahElShaarawi

Read More