Why the Subcontinent’s Dynasties Are Falling

Old political dynasties are losing their grip on power as South Asian democracies change.

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi with Pakistani President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his daughter, Benazir Bhutto, Simla, India, July 3, 1972. AP

Nearly seventy years after India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (then part of Pakistan) gained independence, three of the subcontinent’s most prominent political families are in dramatic decline. The Bhuttos of Pakistan, the Gandhis of India, and the Zia-Rahmans of Bangladesh held ruling posts for years, if not decades, but are now at their weakest point since entering politics. Their former voters are increasingly unwillingly to stomach the corruption that has become synonymous with their famous surnames. As democracy in South Asia is maturing, family ties don’t fetch the loyalty they used to.

In their rise to power, these political dynasties followed remarkably similar playbooks. Strong women capitalized on the legacies of their influential (but recently deceased) fathers or husbands to present themselves as a unifying figure at a moment of national transition. Benazir Bhutto led a campaign to restore democracy against Pakistan’s military leader, General Muhammad Zia ul-Haq, in the years after the general’s regime executed her father, former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Indira Gandhi, daughter of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, emerged from a power struggle between the old guard of the Congress Party as a compromise candidate to lead the nation after the sudden death of her father’s successor. And, after the assassination of General Ziaur Rahman, elites from the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) coalesced around his wife, Khaleda Zia.

Building on the legacy of their names won each family decades of extraordinary influence but had a fundamental weakness. These women relied on local power brokers—landowners, businessmen, mob bosses—to subvert the old ruling class (often leaders of the independence fight) and these characters demanded compensation. Upon coming to power, all three families were plagued with endemic corruption, driven partly by political necessity and partly by greed. Bhutto’s husband, Asif Ali Zardari, is infamously nicknamed “Mr. 10 percent” for what he allegedly charged contractors for political favors. Indira Gandhi is widely blamed for introducing wide-scale corruption into India’s politics. Graft was so common in Khaleda Zia’s government that Transparency International named Bangladesh as the world’s most corrupt nation.

The younger generation’s decades of living large has tarnished the public images of these families. Photos of Benazir’s son and heir, Bilawal, partying with several women while at the University of Oxford fixed his playboy image for many. Rahul Gandhi has a similar reputation for being aloof and disconnected from the traditions of average Indians (he is open about having a Spanish girlfriend and his unwillingness to get married). Zia’s son Tarique Rahman is seen as hopelessly corrupt and will likely be immediately arrested if he ever returns home from his self-imposed exile in London while his mother is not prime minister.

These weaknesses contributed to catastrophic losses for all three families at the latest polls. Zardari’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) not only lost power in 2013, but could not even secure second-place in a popular vote. India’s Congress Party suffered its worst-ever defeat in 2014, winning less than 10 percent of seats in India’s lower house. The BNP, crushed in the last fair Bangladeshi election in 2008, decided to boycott the general elections in 2014, leaving none of its lawmakers in parliament.

The three diminished dynasties have rebounded from political loss before, but this time is likely different. South Asia’s policy inertia and tremendous poverty usually means that several years after an election, voters are fed-up with incumbents and ready to reconsider their options. Pakistanis are challenging the performance of the incumbent government, but they now have a strong alternative to the PPP. Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf won more votes than Zardari’s party in the past election and picked up many former PPP districts. The group is led by a political upstart, former cricket star Imran Khan, and has galvanized Pakistan’s educated urban classes. At one rally, he declared, “We will end the politics of dynasty. My sons will never enter politics.”

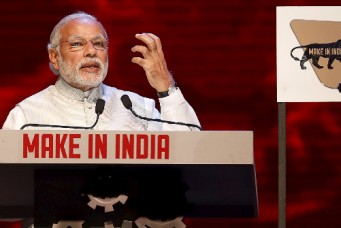

Two years after booting Congress from power, Indians have repeatedly demonstrated that they are glad they did. The party lost four out of five state elections this year, eking out a victory only in tiny Puducherry. Congress responded to this string of defeats by tapping Rahul’s sister, Priyanka, to campaign for them in the “kingmaker” state Uttar Pradesh. It is unclear why this strategy should work given that voters so resoundingly rejected her mother and brother in the last poll. Instead, Indians are turning to regional parties, caste-based movements, and Hindu-nationalist alternatives. At the national level, voters chose the Bharatiya Janata Party which campaigned on an anti-dynasty platform. Party leader and current Prime Minister Narendra Modi has no children.

The exception to this slow evolution is Bangladesh. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, herself the head of a powerful dynasty, has used increasingly authoritarian tactics to undermine her principal rival. After over eight years of being subject to mass arrests, extra-judicial killings, and financial sanction, the Zia-Rahman political network is dramatically diminished. Although most voters in the country are glad to see them go, their decline has more to do with undemocratic pressure than a change in voter sympathies. Unwittingly, Hasina is paving new ground by demonstrating how to extinguish the influence of a rival family through force. Her peers on the subcontinent are watching closely.

When South Asia embraced mass suffrage after independence, it was still a land of princely states filled with illiterate poor. It is little mystery that elites manipulated the poor to ensure power for themselves and their descendants. The unprecedented deterioration of three such families indicates a new direction for politics in the region. Voters, no longer won over by surnames, are demanding choice. These alternate choices are often illiberal, corrupt, and rely on their leader’s populist charisma, but they successfully cater to the demands of a burgeoning educated class. South Asia’s political masters best pay attention.

Faisal Hamid is a reporter-researcher with the Cairo Review.