Doughnut Economics: Living in a Sustainable World

How humanity can transform from traditional growth-first economic policies to a 21st century vision centered around sustainable development.

A protester carries a sign during the “People’s Climate March” in the Manhattan borough of New York September 21, 2014. The international day of action on climate change brought hundreds of thousands of people onto the streets of New York City on Sunday, easily exceeding organizers’ hopes for the largest protest on the issue in history. Carlo Allegri/ Reuters.

As the world enters its final decade leading up to the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), many countries are often set between staying stuck in their economic ways, or transforming to embrace a sustainable future based on sustainable development.

The United Nations explains that development is key to achieving a better quality of life. However, economic and social development, and environmental protection must work hand in hand to ensure sustainable development. However, the world is far from the ideal development standards. According to the UN, 3 in 10 people do not have access to safe drinking water and 6 in 10 people do not have safe sanitation facilities. In terms of food security, the World Food Programme (WFP) said that 135 million people suffer from acute hunger that is due to man-made conflict, such as climate change and economic crises.

And let’s not forget the elephant in the room—the COVID-19 pandemic— and its debilitating effect on unprepared economies and those which weren’t designed to be flexible for such crises.

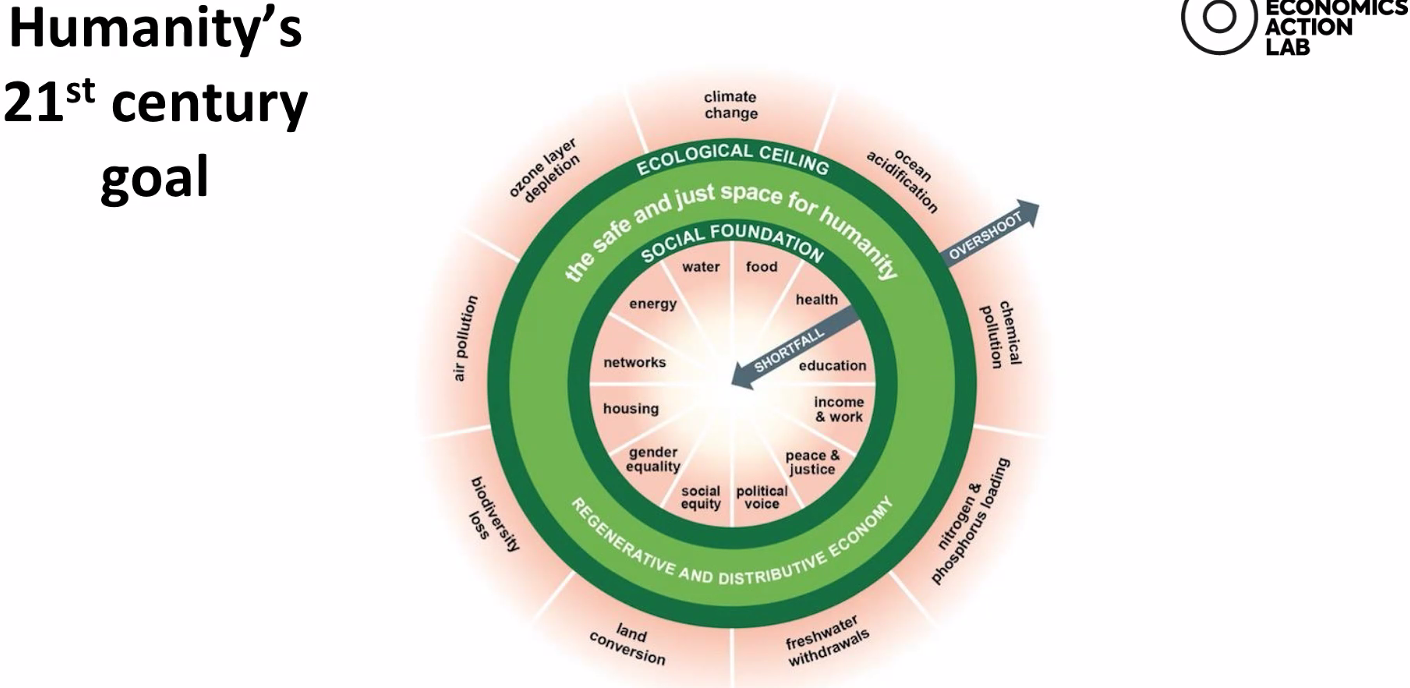

While much of economics is centered around the concept of endless growth, “Doughnut Economics”, which the World Economic Forum (WEF) refers to as the compass for creating “a safe and just 21st century”, puts social, economic and environmental principles at the center of decision-making and public policy enactment.

An internationally best-selling book, “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist” written by Kate Raworth, an economist and co-founder of Doughnut Economics Action Lab at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, and a professor at Amsterdam University of Applied Science, details Doughnut Economics in terms of how this economic theory can be used to meet the needs of the human race; all aligned with the sustainable distribution of resources.

As Doughnut Economics aims to accelerate economic development on the social and economic fronts, Raworth’s book attempts to encompass social foundations with environmental, sustainability, and economic growth. The previously mentioned WEF article details one of her suggestions via the concept of inclusive growth, and early last month, Raworth was featured in the American University in Cairo (AUC)’s Gerhart Center Webinar Series.

In this given time, countries are expected to not only commit to sustainable development, but also to accelerate their progress. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the “successful implementation of the SDGs will require striking a balance between socio-economic progress, sustaining the planet’s resources and ecosystems, and combating climate change.”

The Problem with Economic Growth as an Ideal

During her talk at AUC, Raworth related that much of twentieth century economics centers on the notion of the “rational economic man”. The rational economic man is a stereotypical male figure who, she explained, stands alone over the world with, “ego in his heart, a calculator in his mind, and nature at his feet… He hates work, he loves luxury and he knows the price of everything.” This male character is the image of twentieth century growth-focused economics and it is a rather dangerous vision, because the more this concept is studied, the more economists begin to value self-interest and market competition over collaboration and development.

Raworth explained that, when she was a student in the 1990s, she was frustrated by the traditional twentieth century economic model which gave primacy to growth of the economy over everything else.

“When I ask students ‘what do you remember as the first diagram you learned in economics?’ The answer is the same wherever I go. It is the supply and demand of the market. This is as if to say that the economy is the market, and that puts price at the center of our vision. Anything that falls outside of price is called an externality”.

Even though the United Kingdom (where Raworth calls home) is one of the richest nations on the planet, politicians and economic advisors there still believe that the answer to all their problems is more economic growth.

“The goal of twentieth century economics is never drawn or made visible, but it underpins every political speech, every economic advice, every journal in newspapers, and it is (about) growth. This is not specifically growth for low income countries that need it, but it is growth for whatever level of development a nation is at; no matter how rich a nation already is,” explained Raworth.

A 21st Century Doughnut Economy

Sustainable development is at the core of Doughnut Economics, in the sense that this school of thought works to create an economic system that goes beyond supply and demand. Raworth explained that the private sector and civil society actors need to put sustainable development at the forefront of public policy, or the repercussions for the world and humanity may be unfixable.

“These ideas of ‘markets first’, rational selfish humanity and endless growth, have profoundly underpinned the situation we find ourselves in. The twenty-first century has multiple crises; a financial meltdown in 2008, climate and ecological breakdowns, and the COVID-19 lockdown that we are all enduring,” she stated.

Raworth stressed that the growth/development-first twentieth century economic theory does not serve current economic conditions or lifestyles. The WEF’s website states that while countries consider growth to be a target, the pandemic has proved that the concept of growth can be reimagined so that employment, basic needs, and sustainability are new economic goals of nations and international organizations.

The COVID-19 pandemic also shows how humanity is interconnected and this interconnection encompasses the sharp inequalities of gender and of race, of wealth and power, of the global north and the global south.

Raworth stressed that the current global crises have emerged due to the systems of endless expansion. Present systems all depend on expansion models across various sectors such as financial systems, energy and industrial systems, all of which consume the Earth’s resources. Coupled with loss of biodiversity and environmental degradation, the growth-first economic system has created the ideal environment for worldwide medical pandemics.

“The Only Doughnut That is Any Good For Us”

Raworth proposed solutions for twenty-first century economics, stating that her concept of an economic donut is meant to be understood as a visual representation of the distribution of resources.

As per the diagram above, the central circle has the 12 social dimensions that cover all of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These are the 17 goals that 193 countries adopted at the UN’s Sustainable Development Summit. The goal is for no one to fall short in the middle of the donut in the empty hole. The hole in the middle is where people do not have the resources they need for food, healthcare, housing, education, transportation, political voice and income.

“At the same time, do not overshoot the outer ring, because that is where we overuse the Earth’s resources in a way that we break down the life-supporting systems of this planet. We cause climate breakdowns, we acidify the oceans, and we break down the web of life, so we need to stay between the boundaries,” she stressed.

“The goal of the donut is to meet the needs of all people within the means of the living planet. I believe all economics should begin here, by setting out our vision and goals. If we do not have a goal, how will we know what success looks like? How will we know what a good policy is?” asked Raworth.

While the image above showcases an ideal global scenario, the reality is that humanity has already “overshot multiple planetary boundaries on climate change, on land conversion, and on biodiversity loss” and many around the world are living in poverty, she said.

All Countries as Developing Countries

Despite the fact that the doughnut figure above represents the globe, most policymaking and government decisions take place within smaller circles, namely the leadership of separate countries. Raworth explained that researchers at the University of Leeds created smaller circles for 150 nations.

While Norway is considered to be at the top of the development index and is arguably also viewed as one of the best places to live in the world, the northern European nation is still overshooting planetary boundaries, as is the case for most high-income nations. On the other hand, Egypt has some shortfalls and some overshoots on planetary boundaries. As per the 2020 Circularity Report, Egypt is considered a “grow country,” which means that the best way to navigate development is through sustainability across all areas, such as infrastructure and transportation.

As the world is categorized into low, middle and high income countries, each of the three sets have different impacts on the environment. Raworth explained that low income nations face the challenge of meeting people’s needs for the first time without overshooting planetary boundaries. Meanwhile, middle income nations need to meet people’s needs fully without overshooting planetary boundaries. In comparison, high income countries must meet everyone’s needs because they can afford to; however, they need to exist within planetary boundaries.

“There is nothing advanced or developed about destroying the life supporting systems of the planet. We are all developing countries because we are all in a process of transformation,” Raworth said.

Intertwining Economics With Ourselves

Raworth explained that the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us that when marketplaces have to physically shut down, people realize the importance of things beyond economic growth, such as households, the government and community workers.

During the pandemic, people have become more aware that they weave in and out of identities everyday. She stated, “We may be public servants, residents, voters, teachers, or protestors. These are all crucial roles to play in relation to the state. We are also parents, children or partners, where we do unpaid caring work, usually ‘women’s work’.”

In bringing Doughnut Economics to life, Raworth concluded that, “We have to recognize that the economy is a social construct; it is embedded in society. Society itself is embedded in the living world.”

Dania El Akkawi is associate editor at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs.

Read More