Egyptian Workers in Jordan Hopeful Despite Syrian Influx

Recent studies examine what effect Syrian refugee workers will have on the migrant labor market in Jordan

Ibrahim Awad (Director, Center for Migration and Refugee Studies, AUC); Ms. Simone Troller Alderisi (Regional Advisor for Migration and Development, Swiss Cooperation Office, Jordan); and Ms. Corinne Henchoz Pignani (Director of Cooperation, Office of International Cooperation, Embassy of Switzerland, Egypt) discuss issues facing Egyptian migrant workers in Jordan at the American University in Cairo’s Oriental Hall, January 22, 2020. Audrey Lodes

Egyptians have a 40-year history of working in Jordan, mainly in the service, agriculture, and construction industries. Aided by bilateral agreements between the two countries, minimal entry requirements, and expanded job opportunities, as of 2017 there are an estimated 1,150,000 Egyptian migrants in Jordan (Arab Republic of Egypt Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) 2017). While migration networks have been firmly established between the two countries, the influx of over one million Syrian refugees to Jordan since 2011 has created new market realities. The Jordanian government has committed to providing 200,000 jobs to these Syrian refugees, many of whom work in the same labor sectors, leaving open the question of how this affects Egyptian migrant workers.

“Jordan is the second-most popular destination for Egyptian workers in the world, therefore extremely important as an outlet for Egyptian labor and the labor market,” Ibrahim Awad, director of the American University in Cairo’s Center for Migration and Refugee Studies (CMRS), told The Cairo Review.

Ayman Zohry, a Cairo-based migration expert, Salma Abou Hussein, lead researcher at CMRS, and research associate Darah Hashem interviewed and surveyed 501 Egyptian migrant workers in six Jordanian governorates, and upon their return home.

Their research, “The Impact of the Syrian Influx on Egyptian Migrant Workers in Jordan”, which was presented at a one-day conference hosted by CMRS in late January in collaboration with the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swiss Embassy in Cairo, also examined overall working conditions and individual experiences.

Many of the respondents reported harsh working environments, low wages, and unfit living accommodations, but added their belief that Jordanians rely on Egyptians because they possess required market skills and the physical endurance required in the agriculture industry.

Seventy-seven percent of the Egyptian migrant workers in the three labor sectors believe the presence of Syrian workers in Jordan has affected their working opportunities. The highest concentration (94.5 percent) of those who hold this belief work in the agriculture industry, while 96 percent of respondents from all three sectors reported that this is a result of Syrians accepting lower wages than Egyptians for the same jobs. In other words, cheaper labor.

“The idea behind doing these studies is not just to assess the impact of Syrian workers on Egyptian migrant workers, but to enhance the overall conditions of mobile people in the region. We must first know data; we cannot give a reasonable estimate of numbers because it can be quadruple the official numbers. It is very important to have numbers to make informed decisions,” Zohry told The Cairo Review.

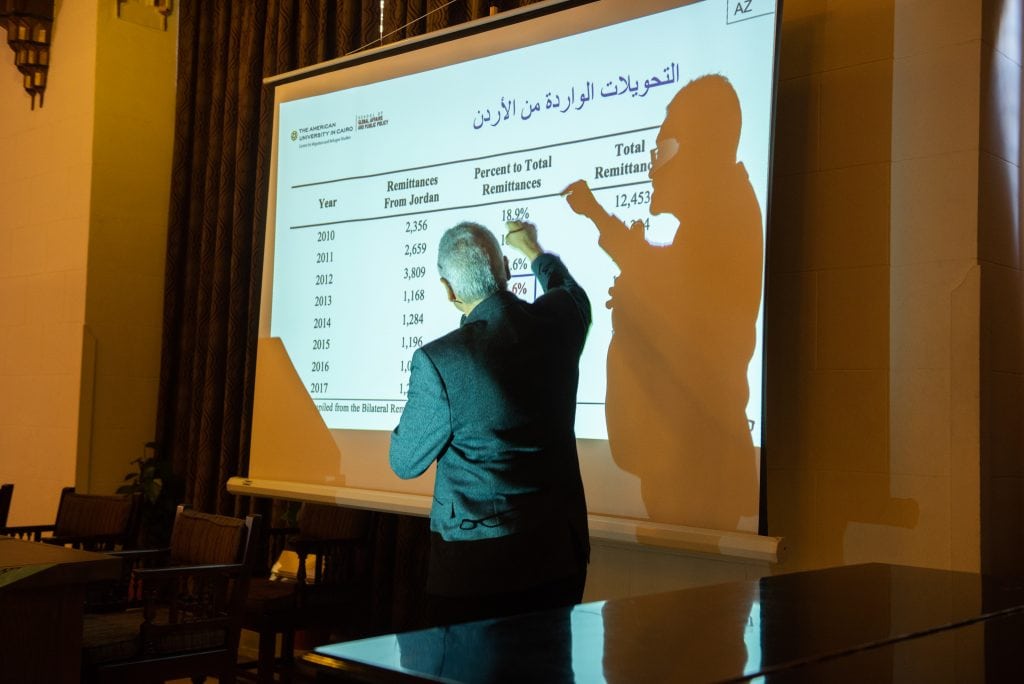

Cairo-based migration expert Ayman Zohry presents findings on Egyptian migrant workers in Jordan, January 22, 2020.

Simone Troller Alderisi, the SDC’s regional advisor on migration and development in the Middle East, said that although Egyptians comprise the largest group of migrants in the country, the large influx of Syrians with work permits may have shifted perceptions of Jordan as an optimal destination for Egyptian migrant workers.

But the current situation is far from bleak. The Zohry study found that competition between Syrians and Egyptians was minimal and heavily dependent on the specific job and sector. Syrians usually work in areas that rely on technical skills, while Egyptians tend to work in industries requiring physical strength like construction and agriculture.

“Egyptian Labour Migration in Jordan” by Dina Abdelfattah, assistant professor at AUC and the chief economist on the study, considered the demographics of Egyptian migrant workers while exploring shifts in supply and demand for their employment.

Abdelfattah believes that understanding the backgrounds of Egyptian migrant workers is crucial for contextualizing their decisions to migrate and key in proposing appropriate policies that will improve labor migration. Abdelfattah found the migrant population to be largely comprised of young, single men from low educational backgrounds seeking temporary work—usually lasting only a chapter in their early lives—in order to save up for financial burdens back home such as supporting a family. She cites an Egyptian migrant worker in Amman, who explains, “First, we as youth aspire to build a future. Second, as you know the situation [in Egypt] does not allow for staying there, saving up, getting married or financially supporting your family.”

Her findings were that working conditions are often poor, echoing the research of her colleagues in the previous study.

“In all sectors, 13 working hours a day are common,” she says.

But Egyptians keep heading to Jordan for work opportunities. Awad says that labor market instability in their home country, the lure of remittances, and the relatively low costs of work permits are the primary factors driving many to seek employment elsewhere, ultimately making Egyptians the largest migrant worker population in the region.

He believes that “[labor migration] relieves heavy pressure on [Egypt’s] domestic labor market and is a crucial source of foreign exchange for its economy.”

Egypt is the world’s fifth-largest recipient of remittances, which are considered the main positive consequence of migration. “If we look at the money that flows between the countries as a result of labor migration, we see that in 2017, according to the World Bank, roughly 1.7 billion dollars have been remitted from Jordan to Egypt,” Alderisi said.

She estimates the average remittances sent by each migrant worker to be between $150 and $300 a month, going primarily to their children and parents.

“We see the benefits these funds bring to health, education, nutrition, and economic development in labor-sending countries,” Alderisi added.

Despite the challenges these workers face, both studies noted the potential positive aspects of migration for both Egyptian workers and the Egyptian economy, in addition to Syrians positively contributing to the workforce in Jordan. For Egyptians, these beneficial outcomes also include skill acquisition and the transfer of knowledge. Zohry’s study showed that about 75 percent of respondents believe they can apply the [skills they acquired in Jordan] when/if they return to Egypt.

Additionally, Syrians in the Jordanian workforce actually present several advantages, especially from the perspective of the local economy. Since 2011, this population is already in-country so the costs of recruitment and expensive work visas are negligible. Syrians also tend to have strong entrepreneurial skills despite, on average, lower levels of education.

Both studies concluded that the migration of Egyptian workers to Jordan will continue. However, the researchers called for regulation and better policies surrounding wages and visas in order to prohibit exploitation and abuse of workers.

The Zohry study suggested setting a minimum wage in Jordan for both nationals and foreigners regardless of refugee or migrant status. This would also close the large gap that exists between minimum wage for Jordanian nationals, and that for migrants and refugees. Another way to level the playing field, specifically between Syrians and Egyptians, would be to set a standard set of requirements regardless of nationality to obtain work permits, medical insurance, and tap into the social security system. Currently, permit costs vary greatly between migrants and refugees, which often leads to unequal treatment.

In order to achieve the recommendations above, Abdelfattah says that there must be more research into these populations, their movement, and labor trends.

Audrey Lodes is an assistant editor and photographer at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. Find her on Twitter at @audreylodes.

Read More