The Future of Work: Between Technology and Inequality

While the future is foggy in light of the pandemic, the importance of technology is real and certain, and the creation of new jobs will pave the way for new global work arrangements.

There was already an ongoing discussion on the “future of work” far before the COVID-19 pandemic plunged the world into a new normal. When the virus hit and every country was forced to navigate new economic, political and social terrains, how people conducted their daily jobs was also affected. While heavy global reliance on technology helped people across all sectors continue some modicum of their work, jobs that could not be continued “online” either forced employees to continue physically working on site, thus risking their health, or were simply lost.

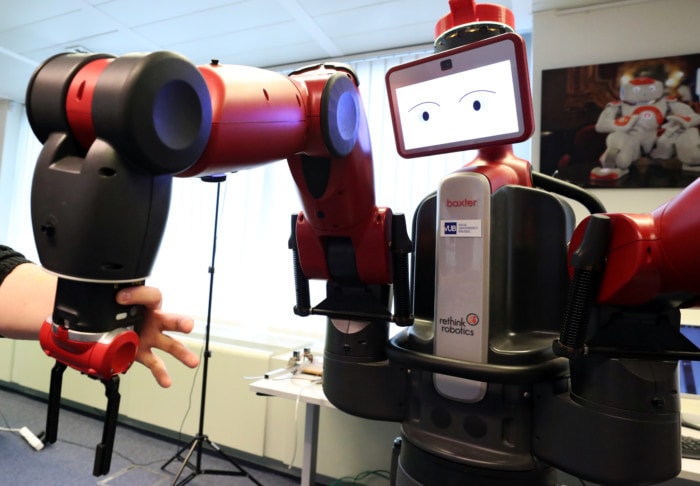

According to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) “The Future of Jobs” 2020 report, the pandemic disrupted labor markets and created a turnaround in technology adoption, job creation and loss. One of the report’s key findings is that the use of technology will accelerate with a “significant rise in interest for encryption, non-humanoid robots and artificial intelligence”.

The WEF report also points out that new jobs will take the market by storm. “We estimate that by 2025, 85 million jobs may be displaced by a shift in the division of labour between humans and machines, while 97 million new roles may emerge that are more adapted to the new division of labour between humans, machines and algorithms,” the report stated. This will be coupled with the need for reskilling labor and increasing jobs that require analytical, problem-solving, and self-management skills.

As part of a session held by the American University in Cairo’s Gerhart Center Webinar Series titled “Decent Jobs and the Future of Work after COVID-19,” Director of the Future of Work(ers) Program in the Ford Foundation Sarita Gupta spoke about the challenges workers face in the current global economy, the growing inequalities, and the impact of digital technology on jobs.

The Narrative on the Future of “Work” Vs. “Workers”

Gupta’s role is to lead a team that oversees efforts to actively pave the way for a better future that positions workers and their well-being at the forefront. “You heard me say the future of “workers”’ not the future of “work” and that is intentional, because at the Ford Foundation, we believe that the future is fundamentally about people. Therefore, we focus on the future of workers and how we can collectively secure a path of shared prosperity and economic security for all workers,” she said.

Gupta also pointed out that when the future of work is being discussed, there is a heavy focus on automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and technology. Inevitably, technology does play a visible role in that, and will continue to play an even greater role as the years go by. However, the conversation is framed around how businesses and employers can use technology to increase efficiency and productivity, and deliver value for consumers and shareholders. Gupta explained that this narrative is often dismissive of those who carry out the work, including low- or middle-wage workers who make the global and local economies function.

And global economies have been severely strained under the pandemic. According to IMF estimates, the global economy shrunk by 4.4 percent in 2020, which is described by the BBC as being far worse than the 1930s Great Depression. According to the article, the only major economy that grew in 2020 was China—by 2.3 percent—and in 2021, the IMF is predicting a global growth of 5.2 percent, led mainly by countries such as India and China.

It is worth noting that Egypt has performed well economically despite the pandemic. “After recording a growth rate of 3.6% in FY 2019/20, growth is projected to reach 2.8% in FY 2020/21, with a modest recovery in all sectors except tourism, as the pandemic continues to disrupt international travel,” according to the IMF.

But in light of all these global challenges, the Ford Foundation’s mission of focusing on modernizing social contracts and labor policies, reimaging capital flows and markets, and fostering responsible innovation and technology, can be a difficult task, especially as the nature of work is rapidly and permanently changing.

The Inevitable Changes to the World of Work

The economic and social disruption of work threatens the long-term livelihoods of millions, stressed Gupta. However, it was well before the pandemic that the “world of work” was already headed in a new direction. Technology, climate change, globalization, and demographic shifts were already leaving unremovable marks on the way people worked, and the way work is structured globally.

The WEF’s “Future of Jobs” report says that by 2025, the number of work hours performed by machines and people will be the same, and this will lead to the creation of new jobs that depend on AI, robotics, software engineering, machine learning, among others.

“With respect to new technologies, AI, automation, and robotics will create new jobs. The question is whether or not these jobs will be good-quality jobs that provide people with what they need to live sustainable lives,” said Gupta. She added that while job creation is critical in keeping the economy up and running, the discussion around new jobs is often an “either-or” scenario in the sense that “we either create jobs or create good-quality jobs”. On that point, Gupta said, “We need new jobs, and they need to be good quality jobs”.

It is important to realize that the people who lose their jobs to emerging technologies are those who are least equipped to seize newly created jobs. Another challenge workers are faced with is demographic shifts. “Expanding youth populations in some parts of the world, and aging populations in others, will create new pressures on markets and social security systems,” explained Gupta. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), demographic change has an impact on all countries while related issues such as decreased fertility rates, increased ageing populations, and youth unemployment are among the numerous challenges to job creation and global sustainable development agendas.

Climate change is another key element influencing the future of work. The International Labor Organization (ILO) states that climate change will have profound impacts on employment across many economic sectors due to extreme weather conditions, including heat waves, heavy rainfalls, and increases in droughts and natural disasters. Job losses in urban areas will be a result of worker displacement and physical damage to businesses and infrastructures. In rural areas, damage to agricultural crops is also to be predicted.

On the other hand, the move to technology would be a harbinger for positive major changes, ranging from utilizing clean energy to using less paper. “The greening of our economies, as we adopt sustainable practices and clean technologies, will create new jobs. However, other jobs will disappear as countries scale back their carbon-resource-intensive industries,” said Gupta.

Because the world is becoming evermore interconnected, more so due to the pandemic, globalization can also play a key role in creating new jobs, and in spreading the way and structure in which work is shifting across all regions. In many developed countries, the structure of work has shifted away from what has been known as “mega firms” of the past,” added Gupta, explaining that “mega firms” of the past would employ and provide benefits for large workforces across a range of skills and income levels. However, Gupta elaborated this is shifting toward more “nimble firms” that have light footprints in employment. Nimble firms, while being more effective, efficient, and agile in the face of challenges, rely on a “a fluid army of contingent workers,” she said.

Firms are constructing networks, subcontracting, outsourcing, and franchising work to allow them to streamline operations and cut costs, specifically labor costs, by avoiding the responsibility once attached to the standard employment relationship of the past, said Gupta.

Agility Above All: Challenges & Solutions

During her presentation, Gupta referred to the ILO’s 2019 “Future of Work” report, which revealed several interesting statistics including that by 2030, 334 million jobs will need to be created. This is in addition to the 190 million jobs already needed today to address unemployment. Of the 190 million unemployed people, 64.8 million of them are youth.

The statistics also revealed that when it comes to working conditions, 300 million workers live in extreme poverty and 2 billion people make a living through the informal economy. Interestingly, in Egypt, the informal sector represents more than 50 percent of the country’s economy. Government efforts are being made to bring the informal economy into the formal one. This reform, expedited due to the pandemic, would pave the way for financial inclusion, which Gupta believes is a global problem due to the immense concentration of wealth among the “super rich”. This particularly includes eight men who “own as much wealth as half the world’s population.”

An article published by Reuters in 2017 detailing the WEF’s annual meetings in Davos lists the eight individuals as “Bill Gates, Inditex founder Amancio Ortega, veteran investor Warren Buffett, Mexico’s Carlos Slim, Amazon boss Jeff Bezos, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Oracle’s Larry Ellison and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg”. “The concentration of wealth in our global economy will determine how innovative technology is deployed and in whose interest they operate,” said Gupta. While new technology has a great potential to create new wealth, there is no economic law that says the wealth will be well-employed, she added.

Gupta stressed that the problem is not if new technology will eliminate or create jobs, it is rather about who is driving the change, why they are driving, whether there will be accountability for how change will happen, and who will be advantaged and disadvantaged by said change. “The fundamental question we have to address is about power, and those with power suggest an inevitability of inequality,” she said.

The silver lining, however, is that the technology is not an unstoppable force that “happens to us”. Gupta said that people can shape technology in a way that will improve economic security, opportunities, and dignity for all working people. “When navigating new technologies, we have to ask “who benefits?” Does the application of new technology, or shifts in work, speed up the concentration of wealth into the hands of a select few, or does it allow communities to get fair shares of the wealth they are producing?” she asked.

One of the United Nations seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. The global goal here is to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”. This is in line with the ILO’s Commision on the Future of Work. The ILO’s decent work agenda promotes the following four pillars: employment creation, social protection, rights at work, and social dialogue, and these have become critical aspects of the 2030 global agenda. It is through global partnerships that promote ideas such as these, and bringing everyone to the same decision-making table that a better future can be achieved.

Dania El Akkawi is associate editor at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs.

Read More