The World To Be

World experts discuss future global developments such as the rise of Asia, the impact of demographic changes in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, and the role of the Global South in the world.

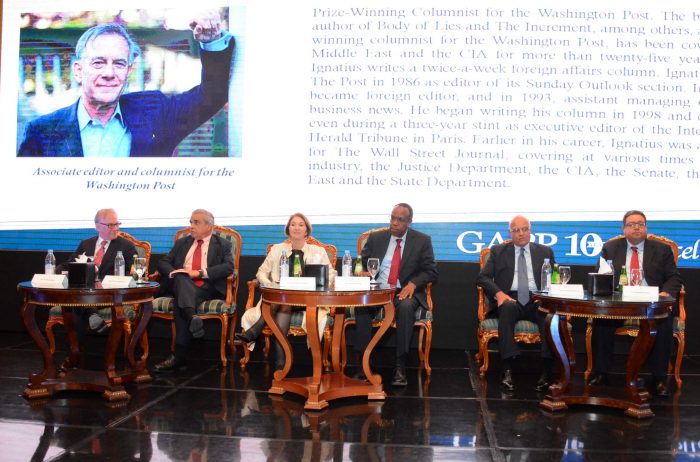

At the tenth anniversary celebration talk of AUC’s School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, Nile Ritz-Carlton, Cairo. March 31. 2019.

On March 31, a slate of distinguished experts from around the world convened at the Nile Ritz-Carlton to celebrate the tenth anniversary of AUC’s School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, and to discuss a deceptively simple question: “Where is the world going?” Moderated by David Ignatius of the Washington Post, the discussion ensued with three key talking points: do Asian economic powerhouses like India and China threaten Western dominance? Will demographic change spur political and economic development in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa? And in the business of re-setting global norms and policies, should the Global South get a seat at the table?

For Singaporean ambassador and professor Kishore Mahbubani, and author of the controversial book Has the West Lost It?: A Provocation, the era of North American and European leadership in the global community is coming to an end. In fact, Western domination only spanned two centuries in recent human history, from the Industrial Revolution starting in the eighteenth century up to modern times. Rapid economic development in India and China, as well as in the other major emerging economies of the “E-7”—Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Indonesia, and Turkey—heralds the dawn of a new power structure. The new order will see the “Western gift” of democracy applied to Eastern civilizations. “The reason that Asia is coming back,” Mahubani said, “is because of gifts from Western Democracies. Asia needs to send the West a big thank-you note.”

American legal scholar and international relations expert Anne-Marie Slaughter, on the other hand, expressed significant doubts about the degree of political, social, and economic integration present within the E-7 grouping. Comparatively, countries which include the world’s largest advanced economies such as Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—otherwise known as the G-7 countries—outdo the “Eastern” countries in those categories. The Princeton University professor argued that the West’s liberal democratic values, rather than upheaving winds of change, will ensure that it continues to dominate the global arena, despite President Donald Trump’s attempt to weaken them.

Both Mahbubani and Slaughter agreed on the authority of Western liberal democratic values and free markets—principles that Slaughter ascribed to ideological “openness.” But rather than just being anchored to a single region, “Western openness” is essentially ideological, meaning that countries as far south as Brazil and as far east as Singapore can potentially be “Western” for example. Slaughter said: “In 2030, or certainly by 2040 or 2050, the dividing line will be between those countries that are open—open to ideas, open to people, open to data. Those countries will be open on the one side, against those that are closed on the other.” This fits with her theory of “collaborative power” that she outlined in a 2011 article for The Atlantic, which goes as follows: cooperation among liberal democracies is more effective and desirable than a unipolar model of international affairs, in which one state or region calls the shots.

Turning to the Global South, George Njenga, executive dean of Strathmore Business School and Ziad Bahaa El Din, founder and managing partner of Thebes Consultancy, expressed hopes for Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. They believed in the momentum and inevitability of change pushed through by demographic shifts that would spur economic and political development in their respective corners of the world. Ngenda and Bahaa El Dine suggested that the Africa and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) regions possess great potential due to their growing populations, which may stimulate regional economies—as long as the southern half of the African continent, which has long been excluded from major global policy decisions (at best) and colonized and enslaved (at worst) is given a seat at the table.

Njenga stressed the importance of regional economic integration and advocated greater collaboration between Sub-Saharan Africa and MENA region, which have traditionally been divided by linguistic, cultural, and political factors. El Din stressed the possibilities latent in Arab youth. As the percentage of young Egyptians continues to grow, political change will inevitably correspond with more liberal, democratic voices. However, rather than a redo of the Arab Spring, he implored Arab youth to participate within pre-existing political structures, including the current government and military, rather than call for an upheaval of MENA’s military-backed regimes.

Indian diplomat Shivshankar Menon posed a final question: if the world is improving, and the world has been brought closer together through the forces of globalization and an increasingly united economy, why are politics becoming nationalistic and divisive? Our smaller world, he argued, has threatened individual identity. Still, the ambassador was optimistic that a more stable, multipolar world could be forged, with a more democratic division of power among regions on the global stage. He joined other panelists in their vision of a world characterized by shared power rather than the clear dominance of particular states.

Finally, at least one potential portrait of the world was illuminated: we may witness challenges to Western hegemony in the spheres of international relations and business; observe the rise of India and China as global political players in addition to economic superpowers; see the implications of demographic shifts in various parts of the developing world, and especially the MENA region and Sub-Saharan Africa in triggering rapid economic growth, improved quality of life, and a marked difference in global political clout. Key to all predictions is a greater spread in the balance of power. Ultimately, in the words of Anne-Marie Slaughter, only one thing is certain: “The great powers of the world are not going to stand by and be run by the victors of World War II forever.” Change is coming.