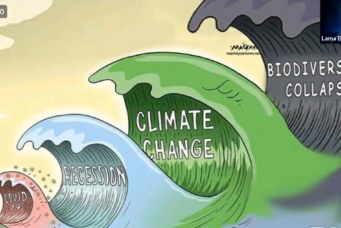

Climate Change: A Global Health Emergency

COP27 Youth Envoy Omnia El Omrani discussed the importance of approaching the climate crisis with human health in mind and co-creating effective policy alongside those most impacted

Source: Africa Europe Foundation

Toward the start of Omnia El Omrani’s emergency medicine internship, Hurricane Irma hit Miami. As a second-year medical student, she saw firsthand the devastating impact of climate crises on public health. El Omrani has since merged her career in medicine with one in climate change leadership, working with organizations such as the International Federation of Medical Students Association, the WHO, and UNICEF, in an effort to keep health at the core of climate change negotiations.

She emphasizes the need for structuring policy not merely in response to political or economic incentives, but in anticipation of an evolving health crisis affecting individuals and communities. This is of particular consequence for the unrepresented victims of climate change – children, adolescents, and women in poor countries – whose health and livelihood bear a disproportionate vulnerability to its consequences.

Last year El Omrani was appointed the first Youth Envoy to the President for COP27, acting as the conduit between youth-led organizations and the government to ensure that the voices of young activists and advocates are taken into account by institutions during the negotiation process.

In light of her expertise at the intersection of medicine and climate change, Cairo Review Assistant Editors Ana Davis and Andre Mikhail discussed with El Omrani youth involvement in COP27, mental health in the climate change era, effective climate policymaking, and the fossil fuel industry’s influence on the health sector.

CR: In the past, you’ve done work on the gap between planetary health and its lack of integration in the medical curriculum. Could you speak on that and how our understanding of planetary health has been impacted by climate change?

OO: One of the things that we worked on is bringing health to the policymaking spaces on climate change, such as COP and other UN spaces. The second thing we worked on, and this is something I was very passionate about, is education of students, especially medical students. So we did for the first time a survey of 2,817 schools across 112 countries to ask students in these universities about their curriculum. In each school the students were asked whether climate change was part of their medical curriculum or not, because we wanted to make the case that students and doctors are not prepared to face a climate emergency, despite how it affects health—and it is the biggest global health threat of the twenty-first century. We discovered that less than 15 percent of them had a mention of climate change in the curriculum. And based on that, we worked on creating a curriculum on climate change for students to work on and its integration globally.

CR: Touching on the curriculum, what are the unconsidered implications for health specifically in the Middle East and Africa as a result of climate change? And how can the resources of the medical field and health professionals be used in service of climate change victims?

OO: I think in the MENA [Middle East and North Africa] region, in terms of climate impacts, what is most important is that we are the driest region in the world. And when we look at the water-scarce countries, there are fifteen of them globally, and twelve of them are in the region. So what we would suffer most from is food and water insecurity, which leads to malnutrition, which leads to acute water stress. And this is one of the biggest challenges that as health care professionals and as doctors, we need to be prepared for, especially in children and adolescents.

The second most important thing is heatwaves and how it leads to acute heat stress, heat strokes, and increasing temperature. Doctors and health care facilities need to be prepared to understand how to diagnose a heat stroke and how to respond to it effectively as quickly as possible, especially because there is a huge rise in mortality related to heat in elderly people above sixty-five that is increasing more than ever before.

And then there’s also the mental health impacts related to heat, but also related to, especially in young climate activists, lack of funds, lack of political action, and a lack of climate urgency. And this leads to anxiety known as eco-anxiety, and stress, and depression, and worry about the future, especially in young people, who also worry about food and water and security. There’s also the terminology related to ecological grief, because now there’s crop failure, so you see—like loss of food—loss of income, but also extreme weather events, such as flooding and wildfires, which is also very common in the MENA region—in the past years in Tunisia, Algeria, Lebanon—the wildfires lead to acute injuries, but also the destruction of houses and schools and universities, and deaths as well.

CR: It seems like mental health isn’t talked about as much as physical health when discussing the health impacts of climate change. Is that somewhat of a new conversation that’s being had?

OO: The reason why I moved to the UK is that I started a fellowship on climate change and mental health at Imperial College, because I was very interested in that intersection, and to understand more. What is the evidence out there and what are the solutions? So what we are doing right now for the next year is developing a series of dialogues on the global level and seven regional dialogues to bring in and to build a community of practice of linking the climate change community and the mental health community—the mental health care professionals and advocates together with the climate scientists and leaders and policymakers—in this space to understand how to really respond and to understand what are the mental health impacts of climate change, what are the interventions and the solutions, but also what are the co-benefits of climate action to mental health. For example, when we are working toward creating cleaner air, cleaner cities, more access to green spaces, we’re also increasing mental health and building resilience to the climate change impact on health. But at the same time we need to understand and quantify what are the impacts of climate-related events on mental health.

[Earlier this year], we launched this project that is funded by Wellcome Trust and led by Climate Cares at the Institute of Global Health Innovation. We’re bringing in, to the center of these dialogues, working groups. We have a working group for young people and a working group for people with lived experience and indigenous communities to co-create these dialogues together with the regional partners.

CR: Would you say that there are areas of dependence between the health care and fossil fuel industries?

OO: We saw from the COVID-19 pandemic that our health care systems are weak. They are not resilient to withstand any crises, not the pandemic, nor the climate crisis. But at the same time, we’ve also seen that the healthcare sector as a whole contributes to around 3.5 percent of the global carbon emissions, and this needs to be changed. Health care facilities need to be more environmentally friendly, to use renewable energy resources instead of using fossil fuels, and to also reduce the waste that is coming from the health care facilities, and to really adopt an environment-friendly net zero carbon approach. And this was done here for the first time in the UK where the NHS [National Health Service] committed to being net zero by 2050, and other health care facilities are now doing the same in the United States, in Kenya, and in other countries. In Glasgow, the World Health Organization launched a set of commitments where countries will commit to be climate change resilient and environment friendly, and they had over fifty countries commit to this. So health care facilities can also lead by example as a sector that is in its core promoting and protecting the health of the people; and it should also respond to climate change and not contribute to the carbon emissions that are leading to the climate crisis.

CR: Something you’ve spoken about in the past is the importance of creating climate plans that are “gender sensitive”. Could you explain what this means and how incorporating a gendered perspective can contribute to more transformative climate policy?

OO: In terms of gender, this is very important, because, first of all, understanding what “gender sensitive” means [is vital]. Because when you look at the evidence, women are disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change. When we look at air pollution, for example, more women are killed by air pollution. When you look at climate-related disasters, more women lose their lives during such catastrophic events. At the same time we see how climate change also affects the maternal health services, but also access to sanitary products, especially during menstruation, and all of these different impacts that women are disproportionately affected by.

But at the same time when we look at the representation of women and climate leadership, their presence at events such as COP, and also their presence, or being part of national leadership positions related to the environment and climate change, there’s still more to go. There is a commentary I worked on in terms of how women leadership in climate change and planetary health has been. Yes, there’s yet more to do, especially with very low presence at COP, and so on. And this is why there is a Gender Action Plan that is being implemented right now that is being discussed. This year we have the Global Stocktake process, which means that the UNFCCC is going to assess whether countries are on track in terms of the climate commitments or not: Are they responding to women? Are they responding to young people? Are they integrating the voices of the most vulnerable, especially indigenous communities and local communities in their commitment, and in their climate plans? And this year we’re going to assess that and the outcome is going to influence the next set of national climate plans that countries are going to develop for the next five years.

CR: Moving on to COP27, could you speak to the significance of the COP President appointing a Youth Envoy for the first time, and also talk about what your responsibilities were during COP27?

OO: Every year at COP since 2009, and before that, young people have been attending COP. But they did not have any meaningful way of bringing in their perspective and their calls to action at global leaders who are at COP. So to really bridge the gap between young people and the Presidency, we decided in Egypt to create a position of a Youth Envoy to be the link between the challenges, the demands, and the voices that young people or young leaders have, and the Presidency and the work of the Presidency.

So my responsibilities were to listen and to consult the different youth-led organizations, groups, and advocates and activists in this space, and to bring in their demands and the challenges and the solutions that they are proposing directly to the Presidency to then integrate that into the negotiation process. The second thing is to build the capacity of the young delegates that are coming to COP to understand the different entry points and the different technicalities, and to support all their youth-led initiatives, campaigns, and work toward the conference itself. The third thing is to create intergenerational dialogue. So a meaningful space where young experts can come in with the negotiators, the chairs of the country groups, and the ministers, and have a meaningful intergenerational conversation with outcomes that we, as the Presidency, integrate in the outcome decision of COP. And the final thing is to really elevate the voices of young innovators, entrepreneurs, and solution makers, and really change the narrative from young people being seen as victims, but as actors and natural partners to the climate agenda.

CR: What efforts were made at COP27 to center the voices of youth?

OO: So in terms of, first of all, the efforts of the Presidency for youth and the highlights is that for the first time we had a Children and Youth Pavilion, which was a dedicated youth-led space that is made for young people, and led by a steering committee of ten youth-led organizations right at the heart of the negotiation zone or the Blue Zone. It is a space that we had for two weeks, and we had events running from 9 to 6 and 7 PM every day. We had over eighty-eight events taking place at the Pavilion. We had the COP President himself come to the pavilion and speak with the young people, and have these dialogues in a way that was meaningful, but also youth-led at its core.

The second thing is that for the first time we had, during the Children and Youth Day, an education session for children and adolescents where we invited the children to present their work, their efforts, their demands, in a way that was conversational with Ministers of Education to really transform and integrate climate change and school curriculum, and also looking at the climate crisis and the child rights crisis.

The third thing is that we had two round-table discussions. For the first time, we had the young experts on adaptation and mitigation and loss and damage, together with the ministers, the negotiators from the EU, from small state islands, and we also had the chairs of the funding groups of G77 and China, AOSIS. Together in these round table discussions the young leaders were given the floor to speak first and to deliver their demands, and then the outcomes from these round table discussions were all integrated in the COP27 outcome decision, which was adopted by over 170 countries at the end of COP. We also had for the first time the mention of children in the COP outcome decision seven times, and youth were mentioned eleven times. And the dialogue, the pavilion, appointing a youth envoy, were then mandated for the next Presidency to do, so that we make sure that there is a sense of sustainability beyond COP27 in Egypt.

We also had the Conference of Youth (COY) right before COP. We had over 1,000 young people participate at COY. And then the outcome decision, the Global Youth Statement was then presented to the Presidency and then discussed on the Youth Day, so that we also find a way of keeping this beyond just having young people present that statement, but to also discuss it at COP.

CR: Looking forward over the next couple of years, what should top the list of priorities for COP28?

OO: I think it’s amazing that at COP28 there is going to be, first of all, a youth climate envoy or youth climate champion with an amazing team, so that the youth milestones that we did in Egypt are going to be further sustained, and this is very important. And right now there was the project that was launched, which is the International Climate Youth Delegate Program, which is going to fund 100 young people from every single small state island and least developing country to come to COY and to COP28, and the priority would be to really recognize the role of young people in the negotiation—to not just be observers, but to also be co-creating the demands their countries are calling for in the negotiation process.

At COP28, there’s going to be, also for the first time, a Health Day, which is very exciting, and this means that health is going to be recognized more as integral to the climate process when you look at the health impacts, but also the health co-benefits to climate mitigation and adaptation, policies and planning. This also needs to be a priority, because we saw, for example, with COVID-19, which was a health emergency, countries were responding and were mobilizing resources and financing for it. Climate change needs to be the same. It is a health emergency. We need to respond to it with the necessary financing, with the necessary resources, capacity building, but also translating these political commitments and targets into implementation on the ground with a sense of co-creation with the most vulnerable groups, communities, especially young people, and also indigenous people and local communities.

So if I were to choose two priorities, I would first say the meaningful engagement of young people in the climate space. There’s so much more that needs to be done when it comes to that engagement, and how meaningful it would be. And the second thing is to really centralize health at the heart of the climate negotiations to bring in the urgency, but also to bring in that implementation and that sense of climate justice, to make sure that processes like COP are credible and are relevant to what they’re calling on.