Waiting for the Next Act

Orville Schell, the Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society in New York, has been studying and writing about China for more than fifty years. He speaks with Dorinda Elliott about the recent leadership transition, prospects for constitutionalism, dangers of nationalism, need for greater Washington-Beijing cooperation, and this next phase of Chinese history.

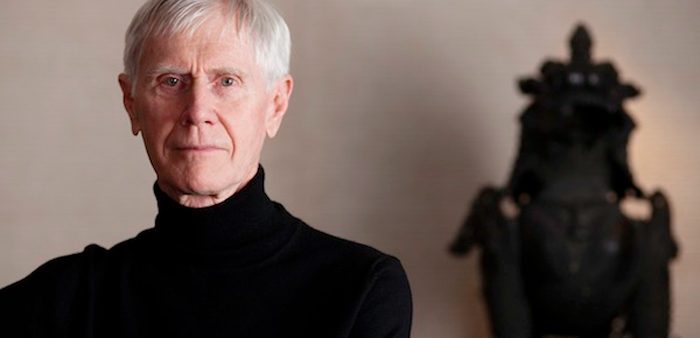

Orville Schell, Asia Society, New York, Jan. 31, 2013. Robert Wright for the Cairo Review

There is hardly any American who knows China as well as Orville Schell. He has been studying the country, visiting it, writing about it, and been fascinated by it, for more than fifty years. He first arrived in Hong Kong, then a British crown colony, in 1961, when China was still an impenetrable, revolutionary nation ruled by Mao Zedong. Even by 1975, when he took his maiden flight into Beijing, China remained, as he would put it, a country lacking advertisements, private cars, fashion magazines, or private property. “There was not a single other aircraft moving on its runways,” he recalled. “It was as silent and dark as a tomb.” The young scholar was able to get a rare glimpse of the isolated country by working for a month at the Communist Party’s model village, Da Zhai.

Schell has been a prolific chronicler of what he considers the “quite epic” accomplishments of the Chinese in the ensuing decades—including the stunning development and modernization that has enabled China to become the world’s second largest economy after the United States. Besides authoring ten books on the country, he has contributed reporting on China to leading newspapers, magazines and broadcast programs, including serving for ten years (1975−85) as a China specialist for the New Yorker. His reporting has earned numerous honors, including an Overseas Press Club Award, an Emmy Award, a George Peabody Award, and an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award.

Random House will publish Schell’s latest book on China in June: Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twenty-First Century. Condé Nast Traveler Global Affairs Editor Dorinda Elliott interviewed Schell on January 14, 2013, at the Asia Society in New York, where he is the Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Chinese with more suggestively liberal tendencies, like former Guangdong Party Secretary Wang Yang, didn’t make it on to the standing committee in the leadership transition last November. How do you view the new Chinese leadership?

ORVILLE SCHELL: You know, the Taoists have always spoken of an un-carved block, and I think that we should look on the new Chinese leadership as being something like that. Both as individuals and as a whole, they are still roughhewn. It’s curious, but it seems that what is required to now get into office in Beijing is not to make yourself distinctive, not to take positions that give out a clear public persona, not to gain popular support, but to be as blank as possible. And, so, it’s really hard to know where this leadership is going to go. Basically, what we’ve had so far, in terms of the leadership defining itself, is very little. We outsiders have engaged in a lot of projections onto them. But, I don’t think anybody knows which projections will end up being correct. It’s quite amazing that this country of such enormous consequence has leaders that have managed to keep themselves so blank. Indeed, it’s truly incredible!

DORINDA ELLIOTT: When [newly elected Communist Party General Secretary] Xi Jinping made his first official trip, to the south, where some liberal economic policies were suggested, lots of people said “Aha! You see, this means he’s a reformer.”

ORVILLE SCHELL: I think it hints that he’s a reformer of a kind—of Deng Xiaoping-type of economic reforms, but not the progenitor of other kinds of reform. And also, I think one can interpret Xi’s actions to date as him seeking to go back to the only source of legitimacy that this dynasty has known, namely, back to its grand progenitor, Deng Xiaoping—to gain some new luster by walking back through that piece of history again. That’s why Xi immediately went to Guangdong, just as Deng did in 1992 when he wanted to re-kick start China’s economic reforms after 1989.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Even Hu Jintao having been in office ten years—

ORVILLE SCHELL: Ten years and we hardly know more about him ten years later than we did when he entered—what he actually believes. We can, of course, see what he did, but even that doesn’t tell us very much about what he believed. It tells us what he was able to do. Most people say it was ten lost years and accuse him of being stiff and rigid, and basically a failure. I look at it slightly differently. I mean, during his tenure China had ten pretty good years! Nothing went too wrong!

DORINDA ELLIOTT: There has been tremendous economic growth—

ORVILLE SCHELL: Yes, but put another way, there was no great disruption, and that’s the name of the game, for these guys. It’s “keep things stable.” So I think, in a certain sense, even though personally I don’t think he was a great leader, you have to acknowledge that at worst he prolonged a big bump, and at best, he enabled China to get ten years further down the line, to get developmental foundations more firmly built.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Some Chinese experts are saying China is facing a crisis, that without further reform, its economy just can’t continue to grow, that the “economic miracle” is going to hit a wall. What does that mean?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Well, we’ve been saying for almost three decades, starting in 1989, that this boom can’t cohere and continue. And yet, somehow it has.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Except now there’s domestic pressure, even sort of officially recognized intellectuals are making these statements—

ORVILLE SCHELL: Yes, echoes of pre-1989. I do feel that they have come to the end of something. And I think many people are now feeling a sort of fin de siècle air about things. The question is, of course, what is the next episode of this long drama going to be? Nobody quite knows. But I have to say, this whole progress with China over the past twenty-five years, none of it quite made sense, and yet it happened.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Right!

ORVILLE SCHELL: It just didn’t seem likely. Who among us did not think that the Chinese Communist Party’s days were over in 1989? So, you have to wonder at our abilities at prognostication. I don’t think that Chinese leaders have any great wisdom that we don’t have. And, I think they’ve been incredibly lucky. But, they have evinced kind of an amazing guerilla flexibility. The ability to roll with the punches and to be at once opportunistic and also pragmatic. But how much further can they get on more tinkering? Well, it’s anybody’s guess. But, it seems to me that, at some point, they’re going to have something like an earthquake. Why? Because unrelieved tensions build up on the fault line and inevitably seek release. And then suddenly you get a rupture.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Lots of Chinese economists are saying that China now needs to move away from the state model and so much emphasis on the state-owned sector to promote more private enterprise. But there are so many vested interests, right?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Yes, but it’s frightening to the party to have the state shrink to the point where a tipping point is reached, where the state loses so much musculature that it loses influence. That could happen, if the big state-owned monopolies begin to be challenged.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: So a shift to a more privatized economy could be a scary thing for the leadership?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Yeah. The government loses clout. It loses influence in the resource base and begins to have to contend with too much private power and influence.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: So Americans and Chinese pushing for rapid change should be careful what they wish for?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Always.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: A China that collapses because the central government doesn’t have the financial clout to make things happen is not going to be good for anybody.

ORVILLE SCHELL: In that kind of a new situation, it would no longer have that many critical economic levers in its hands—

DORINDA ELLIOTT: And that’s not good for the United States and it’s not good for anybody.

ORVILLE SCHELL: No. Certainly not if it led to struggle and instability. One thing I’ve really come to appreciate writing this book that I just finished, is that it has never been any Chinese leader’s plan to implement democracy early on in the game. No one has been for that over the last century. Starting with Sun Yat-sen, the plan has always been that China would first have a period of martial law or authoritarian tutelage, followed by a protracted period of guided democracy, and then, only very slowly, reach constitutionalism. And of course the process has ended up taking much longer than Sun. And it was Chiang Kai-shek’s plan. Even, in a way, Mao’s plan. But it is certainly the expressed plan of recent leaders. It was everybody’s plan, and they’ve actually stuck to it!

DORINDA ELLIOTT: What China didn’t have back then is a middle class. So, you now have a middle class that has much greater demands. Can China still get away with the idea of, “We have to do everything for the sake of the nation” as opposed to enjoying life as an individual, which would be the Western perspective? Is the middle class going to be willing to accept that? Or is that willingness to accept authoritarian rule dissipating with modernization?

ORVILLE SCHELL: That’s a very good question. I think that the middle class is very ambivalent. On the one hand, they have needs and demands as they get rich and in certain ways naturally come to want greater freedom and openness. But on the other hand, they want government to protect their interests. After all, they now have interests to protect. And their further interest is in getting even richer. Now at some point, some of them will want a little more than just wealth. But that’s not been that strong an impulse to date. However, the spiritual and the democratic urge—and there’s been a current of tradition for these urges—has flowed through modern Chinese history. But, we in the West have often mistaken that current as being the main one. But I think the main current through this period of history could be better described as the quest for a reinstatement of China to greatness, which has had little to do with democracy. In fact, it has had more to do with authoritarianism.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: China is rising and, finally, is achieving that kind of greatness. At what point can China cast off the burden of the 150 years of humiliation it suffered after the Opium Wars, which keeps making China respond in such a paranoid fashion?

ORVILLE SCHELL: It’s not going to be soon. The amazing thing is how far their ability to cast off their victim culture lags behind their actual accomplishment. They’ve accomplished an enormous amount, and history has changed, but their victim culture is as deep as ever.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: And, perhaps, useful at times of political trouble at home?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Indeed! It’s become a whole way of relating to the world! I think eventually they will overthrow it, but you know, we naively thought in the eighties they would leave it behind, that it was over, that the effects of the unequal treaties were gone, there was a feeling, “Let’s get on with it!” But now, we find that they have brought it back. I think it’s very, very deep. So that’s sort of what this book I just finished is about. How deep the humiliation was and how strong nationalism became as a result.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: A lot of people in the States, indeed, in the West, say that China’s rise is a scary thing, that we should be concerned. Is that view misplaced?

ORVILLE SCHELL: I think it’s fair to say, that historically at least, this search for wealth and power has initially been quite defensive—how can we protect ourselves, how can we keep ourselves from being occupied, invaded, etc.? But I also think that there can be a terrible and sometimes inescapable logic that the oppressed yearn to become the oppressor, as a sign of their ending their own period of agonizing oppression. It’s a very understandable human and national urge. But, it’s a dangerous one.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: What’s the evidence of that in China?

ORVILLE SCHELL: You know, when you’ve been pushed around for a long time, or feel you have been bullied, there’s a powerful instinct to want to give some of those people a shove when your time comes to be on top. Just to show them that you have arrived and things have changed. Some of this sentiment can manifest itself in indirect ways, such as in territorial disputes. And I think we see something of this certainly in China’s current relations to Japan over the Diaoyu Islands and the whole South China Sea fracas with Vietnam. The Philippines and Malaysia were like satellite tribute states, and in the case of Vietnam, a country that has recently beat China in a war. And now it could become payback time.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: So that’s a way to view China’s behavior in the Spratlys and the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, where China has been flexing its muscles aggressively?

ORVILLE SCHELL: I think that it gives these disputes a certain dangerous psychological energy. I don’t know how far China will take it, or whether they’ll be able realize that it isn’t finally in their interest to keep pushing this. But, it is a terrible logic in history that, given the chance, the colonialized want to be the colonizers, or the inferior want to be the superior, the dominated want to be the dominators.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: It’s important to remember too that China is not just one China. So many people in China don’t understand how messed up and confused politics is in the United States. The same thing goes for China, right? It’s a whole bunch of struggling forces and factions.

ORVILLE SCHELL: It’s true now more than ever, because China lacks the solvent of a powerful leader, to say: “Listen up guys, I’m the boss! Here’s what we’re going to do!” So, there is now much more of a fractured power structure with a lot more negotiating between everybody. We aren’t quite able to X-ray it and know for sure how the pieces configure themselves, but we have some vague sense.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: How do you think the United States views China right now? Are U.S.-China relations on a pretty healthy footing?

ORVILLE SCHELL: It’s very manic. And I think actually that China would be smart to understand that it’s as good as it’s going to get, with President Obama, Hillary [Clinton] and [John] Kerry—and it’s pretty good, actually. They’re smart, reasonable people, and they’re not trying to push China around, but they are going to hedge their bets a bit. And, it’s not insane that they should.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: By that you mean the so-called “Asia pivot.”

ORVILLE SCHELL: The Americans don’t want to humiliate China, but they’re not going to just say, “Oh, you’re sweet and lovely. We trust you 100 percent. Do whatever you want.” I think they’re smart, realistic people and they’re well aware that when a country is a resurgent power, it sometimes can run off the rails.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: From China’s perspective, of course, it feels like containment. It feels like, “What are you doing in our playground? This is our turf.”

ORVILLE SCHELL: It does. And it’s nothing new! I mean, we’ve been out there since the end of the Second World War! It’s just that we kind of got preoccupied with the Middle East for a while. I think China can make out our Asian presence what they will, and there’s no arguing with someone who has a viewpoint that’s born of an emotion rather than the logic of the situation. They can tease things out of the situation to back up their view of being contained, but it doesn’t make them right. I think the U.S. would far prefer not to have to be wary about China. You know that expression in Chinese to “find bones in an egg”? I think the Chinese do a bit of that. They make the world conform to their view of it. Even though there are technocrats and engineers who believe in science and logic, there’s also a deep emotional fire that still burns within that was born of history. And the Communist Party has tended to excite it and use it, as much as to allay it, and bank it. I think in certain critical ways the Chinese have blown it. You know, in a matter of a few short years, they’ve move from “peaceful rise,” that reassured their neighbors, to a very aggressive forward posture. They’ve completely pissed off everybody. Why do that? Unless it benefits you? I suppose, because you’re getting some charge out of it.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: There’s no logic to what’s going on in the Diaoyu and Spratlys. It’s purely emotional.

ORVILLE SCHELL: It’s not in China’s self-interest, so there has to be some other pay-off, and I think it must be some kind of psychological pay-off—at last, being able to throw their weight around a little.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: And that all plays well domestically in China, right? To look like they are playing tough.

ORVILLE SCHELL: It does. But, you know, Deng Xiaoping on the other hand, he was a very able and strong leader, and he was able to counsel: “Keep your head down and bide your time.” The new leaders have sort of cancelled that admonition, and what they say now is: “Well, that that was then and this is now.”

DORINDA ELLIOTT: If I were sitting in Zhongnanhai [the leadership compound], knowing that there are more than 180,000 protests around China every year, probably more, I’d feel pretty nervous about what’s going on.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Nationalism is a little bit like using that fire retardant foam they spray on airport runways before someone crash lands. That’s the way they experience these protests—as a way to extinguish the possibility of further conflagration. This may seem somewhat counter-intuitive from the outside, because they’ve got actually quite a bit going for them. Their recent accomplishments have been quite epic. And yet, because the government has so few sources of legitimacy, it gets panicked by any kind of unrest. It’s so used to controlling everything, that when some things somewhat get out of control, it kind of overreacts. You look at India. The place is blowing up left and right, every day, and people just view it as part of business-as-usual.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: The social tensions that China experiences these days: excessive taxes to forced land grabs; official brutality, rebellions in the countryside; state-owned enterprise lay-offs; loss of retirement pensions, all leading to protests and riots in the cities; demands for freedom of spiritual beliefs; ethnic-minority demands; and even Hong Kong is becoming obstreperous. And finally, growing concerns about the environment. When I look at a list like this, I think, why hasn’t there been another revolution?

ORVILLE SCHELL: The reason for that is that China’s leaders have managed to make so much economic progress. I mean, look what they’ve done. And, whatever you think of their program, they’ve done it. And, it has transformed the face of China from “sick man of Asia” to superpower. There may still be a lot of problems, but many people now have a much better life. Look at all the damn new urban cities and skylines, look at the transportation systems, look at all the infrastructure they’ve built. Even if the whole thing blows up tomorrow, they’ve laid down a century’s worth of infrastructure. It’s an incredible accomplishment.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: It’s beyond imagination.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Indeed! People may still have a lot of grievances, but there’s still a promise of getting in on the spoils of an expanding universe through further development. And that is a powerful promise for many.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: I finished reading Garlic Ballads by Mo Yan, who just won the Nobel Prize for Literature amid lots of controversy. It describes a brutal life in the countryside. I think it’s important to remember just how bad it is in the villages, and just how, even though it may have not looked like much to us Westerners, life has improved a little bit for these people who moved to the cities. Life is tough, but it’s better than being stuck in a truly feudal environment.

ORVILLE SCHELL: True. But, even most of the villages are better than before. It was pretty bad. I mean, if your baseline is the Great Leap Forward, it is far better! I am always amazed when I go out to remote areas like Guizhou, China’s poorest province. It’s still pretty incredible what you find. There are roads and there’s power. The stores are full of goods. Of course, there is also grinding poverty in rural areas. But, it’s materially light years better than before. In these areas the real problem, and this is quite traditional, is the local corruption and local malfeasances in office. It’s pretty extreme in some places. And it’s born of the toxic marriage of the state owning the banks and property. So you get these big land grabs. There’s no private property, no protection. Local officials control property and can get money from the banks, so they take land from peasants for a pittance and make a killing.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: There’s talk of rule of law, but there are no real checks and balances.

ORVILLE SCHELL: When real push comes to shove, for little stuff, the law can work. However, for big things, everybody knows the law is suspended in the interest of the party and the state. And, when corrupt local officials represent both, ordinary people have little recourse to remedies.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Xi Jinping has been pushing the crackdown on corruption. Do you think it will go anywhere?

ORVILLE SCHELL: When you have a system where people are only paid a couple thousand dollars a month at very most, and they have access to all this property and all these bank loans, and they know there’s no way to get things like stock options, it’s an incredible temptation. So, in a certain sense, people are taking what they think they deserve, and then some, by nefarious means. The system is so weird, caught between communism and capitalism. It’s so out of kilter in terms of the norms of the modern world. If you’re working in a state-owned enterprise and you’re making a thousand, max two thousand, dollars a month, and you’re doing deals worth a million dollars, and you could break off a couple of hundred thousand into a foreign bank account, well, you might find it an irresistible temptation.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Like, you’d be an idiot not to do it.

ORVILLE SCHELL: It takes a really moral person, but then you have to ask, toward what honorable end besides their own honor would they be serving? They used to be able to justify such behavior by saying that they were helping the country, building the party, or promoting revolution, whatever. But now, what’s the ethical imperative to be straight? There really isn’t any. People might even consider you a sucker, if you are too upright in this new world where wealth rules.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Is China’s quest for natural resources around the world going to inevitably lead to a conflict with the United States and with the West? How is that going to be resolved?

ORVILLE SCHELL: That doesn’t necessarily have to lead to a conflict, because we’re all sort of in the global market place and in this strange new world where we share so many commons that we actually have a lot of common interest—even though we do not always immediately see it. But, China has a very Victorian notion of sovereignty and national interest. The leaders do not feel they can trust international regimes that encroach on absolute sovereignty. They think: “We need to own the resource we need. We just can’t trust international markets, because they have traditionally been loaded against us. The market might shut us out.” So, they think, we’ll own oil wells in Sudan, copper mines in Afghanistan, other mines in Congo, etc. I think the United States has tried to integrate China into the orderly world market in a somewhat exemplary way. But because of a lot of history, China still distrusts our motives. And so they’re very aggressively moving around the world vacuuming up resources. You can’t fault them for that, actually.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Because they’ve got a big economy they need to keep moving.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Because they’ve got a big economy that needs huge numbers of natural resources from outside of China. And, now that they are wealthy and more powerful, they can do whatever they like. Actually, I think they find this new prerogative quite exhilarating. And, if we Americans don’t want to get into Africa or Latin America, okay, they’ll go. But, of course, there is a danger that they will do so with a sort of muscular bravado that manifests itself in a kind of truculent unilateralism—something in which the U.S. has also excelled. The Chinese look at U.S. behavior and think, “Okay, what’s fair for the goose is fair for the gander.”

DORINDA ELLIOTT: What about Taiwan, which seems to have, under President Ma Ying-jeou, moved a lot closer to mainland China?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Yes. Here we have something of a success story. And, I think if China is smart, they’ll just lay off Taiwan, not push it, and just wait. At some point I do believe Taiwan and China will come back together again. When will that be? When China becomes more democratic. And there’s nothing anyone can say or do before then that’s going to make the Taiwanese feel comfortable. So, Beijing should just forget it for now and be pleased with the status quo with everyone making money. You know, they have a relationship that’s now pretty good. They’re trading like crazy. Beijing ought to count its blessings and recognize that the time for betrothal has not come. They are just living together, and they’re not going to get married for a while.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: There’s an assumption there that China is going to somehow become democratic?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Well, Jeffersonian democracy is not going to spring out like Athena from the head of Zeus any time soon. But, I do think China will eventually have to broach the subject of political reform. That will ripen the situation for a closer reintegration with Taiwan. You also have to hand it to China’s leaders. They have been evincing much forward progress, at least in terms of economic reform. And in what they’ve been doing, albeit with some terribly savage train wrecks along the way, preparing for the next stage of their development. They have been laying the precursor stages for the next act of the development drama.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: What do you mean by that?

ORVILLE SCHELL: They are becoming more unified, building better infrastructure, becoming wealthier, developing a middle class, becoming more worldly, and better integrated into the global economy. They’ve even begun to restore some degree of traditional culture that was so savagely attacked during the Cultural Revolution. When the Qing Dynasty fell, they thought they could have a republic in 1912. But, when you look back on that period now, you realize that such a hope was an absolute pipe dream. They simply were not ready. The pre-conditions had not been laid down. But that is no longer true. It’s still going to be very, very hard, but it is much more likely that constitutional government could take root now than forty, fifty, sixty, seventy, eighty, ninety, a hundred years ago. So, in a funny way, I look at China as being kind of right on schedule now—just a very much more protracted schedule than was originally imagined.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Yeah. And as they keep telling us, “We’re a very big country!”

ORVILLE SCHELL: And we’re not ready! And, we have no democratic tradition. And, our people are still poor and backward, etc., etc., etc. But in a certain sense it’s an alibi for the party to remain autocratic. But in another sense, it’s absolutely true.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: It drives me absolutely crazy when Chinese say, to me, “Well, we couldn’t have democracy tomorrow!” That is not even what the pro-democracy activists are calling for. They’re calling for more openness, they’re calling for transparency.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Indeed. As Hu Shi said way back in the 1920s, “The only way to have democracy is to have democracy.” In other words, you learn democracy by practicing democracy. But, it still takes stages.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: They’re talking about a freer media.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Sure. It will come. That’s why I think that right now we’re at the end of something. It’s just that the party doesn’t quite know how to lay down the track for the next phase of China’s transition, without subverting themselves and pushing themselves to the point where they’d be put into the ash heap of history. But, in a certain sense, they have been preparing the country in a lot of very important ways for the next act. I don’t quite know how they get from here to wherever it is they’re going. It’s not clear to me. But, there will be another act! History is not fond of standing still. This is what the new leaders have to figure out.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Deng always said “We’ll grope our way across the stones,” but in some ways it looks like there was a plan.

ORVILLE SCHELL: The plan was “more.” More wealth, more power. And, now that they’ve got “more,” the question is: at what point does this system, as it’s constructed, cease to be able to keep generating even more? They just wanted to get wealthy and powerful. Those are the two characters that just keep recurring throughout modern Chinese history. But having attained these goals in large measure, they’ve got to figure out, what’s the next step? There’s a great paradox that occurs here. It used to be that Chinese reformers thought that if they could get wealthy and powerful, and expel the foreigners, respect would come naturally from the outside world. Then they would no longer be this abject whipping post for the world. But, now that they have gotten wealthy and powerful, they are beginning to find that respect doesn’t necessarily follow simple wealth and power, and they’re somewhat confused. They wonder: “Why the hell don’t you respect us?” And, so what they’re beginning to discover, but still incompletely, is that to win the respect of the world—which is what wealth and power were supposed to gain them—a country must first also treat its own people with respect. And, the party doesn’t quite know how to do that. And they’re frustrated. They came to the end of this Herculean effort to rejuvenate their country, and there are all these rejuvenations, but somehow it still hasn’t done the trick. They finally got a Nobel Peace Prize, but their laureate, Liu Xiaobo, is locked up in jail. People still think Chinese leaders are somehow not respectable, and it makes them completely insane.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Don’t you think there’s a generational thing? Chinese love to say it’s a transitional stage. It’s just hard for me to believe that the next generation does not understand that.

ORVILLE SCHELL: They are very nationalistic! How many generations have we been waiting for China’s self-confidence to reform? But nationalism born of humiliation is something that sticks to all of them. It’s like genetic material you can’t get off the genome. It keeps re-expressing itself. I think in many ways the people of the eighties were more open.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: That’s definitely true.

ORVILLE SCHELL: And they were somehow less stuck in victim culture than people now, even the young people of today.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: That’s why you can argue that the bloody crackdown on the student movement of 1989 is such a tragic missed opportunity. China was at a crossroads and chose the wrong path.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Even though the 1989 demonstrations could be totally justified in terms of rights, the effect of it was to throw China back into the world over there. They were not only again oppressing themselves, but they were seeing the outside world as savagely oppressing them. It was a terrible throwback to the very syndrome from which they were trying to escape. And, they experienced Western criticism as a new kind of Western exploitation, this time via the media.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: On the environment, I’m reading these reports about Beijing, the air quality index is 750 or something like that, on a scale of 1-500. China’s pollution is extreme, fueled by its need for economic growth. On the other hand, the government has implemented policies and is aware of the problems and is trying to do something.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Over the long haul, I worry less about conventional forms of pollution, like air and water and soil, because actually those you can correct, and we know how to do that. It’s a question of galvanizing the country and spending the money. What I’m more concerned about is energy, carbon emissions, and climate change, which are irremediable and which are going to have a more profound and harmful an effect, not just in China, but on everybody on the planet. And, China will get it worse than the rest of us, because they are more people and it is still quite poor. There are two parallel environmental catastrophes going on simultaneously. The first, we’re very familiar with from the industrial revolution. We screwed up the Hudson River, New York air was wicked, London fog was horrible, the Rhine was a sewer, etc., and then we largely cleaned it up. But this new form of global environmental challenge, which involves climatic changes, is something for which we have no immediate remedy. And it is a direct outgrowth of, not only what we have done in our past, but now of what China is doing presently to industrialize. And, it has all largely grown out of the burning of fossil fuels, especially the burning of coal.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: So where do you see that conversation moving China? Do you think that the need for economic growth is so paramount that it will always prevail?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Because economic development is the major source of the party’s legitimacy, we’re stuck with it. The Chinese leadership is also painfully aware of this problem. But they can’t solve it alone. And with the United States so brain-dead [on climate change], we lack a certain essential leadership. We and they are the ones who should be really collaborating on this. But, for too long the United States utterly and totally abdicated its leadership role. The Chinese don’t always like the Americans bullying and hectoring, even leading. But in this case, I think they would welcome some collaborative American leadership. It’s sort of like a child that is always rebelling against the parent, but when the parent leaves, it gets scary and disorienting.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Let’s be a little bit more specific.

ORVILLE SCHELL: On the question of climate change, the U.S. still has an essential leadership role to play. And, we have not played that role. I think China would actually welcome a stronger partnership here. But, we need to be able to put the necessary resources into it. That would enable us to take the leadership position. The Kyoto Protocol calls for this fund of a hundred billion dollars to help developing nations curb their carbon emissions. Well, it’s not there. I mean, these are very symbolic, but they’re also very real, steps. And, the Chinese notice this absence. The United States has really been paralyzed both at home and internationally. We haven’t signed anything. We are the odd man out. The Germans are spending 1.5 percent of GDP on climate change. Our Congress won’t even recognize climate change. So, how are we going to expect to get together with China on this generational issue? I think they’re willing to do a lot, particularly if there be some kind of a concord on this thing, maybe not setting absolute limits the way Copenhagen was calling for.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: What can they do, if they risk having economic growth slowdown?

ORVILLE SCHELL: They’re going to want to continue growth and to burn coal. But on the other hand, I think they’ll also be willing to pitch in on all kinds of accelerated programs, for renewables, green tech, and all of these other things, which in the long run, could be very meaningful. Four years ago, the Asia Society put together a whole report on this—how a U.S.-China collaboration on climate issues would work. How would they get together to test carbon capture and sequestration? China is the place to do it. It’s cheap, and there are fewer environmental regulations to worry about. That’s how we could jointly experiment on a crucial clean coal technology and scale it up. But, nobody is going to act on it because there’s no money. This is just one example of the kind of things, if there would have been U.S. leadership, that we could and should do with China on a large scale. Alas, the yahoos in Congress would never appropriate money to do an experiment in China, even though it would manifestly benefit both countries, that was cheaper, faster, and more efficient. You never could get support for such a project in this country. So, that’s our curse.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: They’re losing over fifty-eight square miles of grasslands per year because of overgrazing, which to me begs the question on many environmental levels: Is this a matter that the central government just doesn’t have control over the local governments anymore?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Overgrazing is part of it, but I also think a lot of China’s desertification problems have to do with climate changes and changes in rainfall patterns. We don’t really know. I mean, the situation probably varies from place to place, but it isn’t simply a question of land use. In China, the Ministry of Environmental Protection has enormous limits on what it can do. In China the main fault line is between the central ministry, which is very weak, and the provinces, which are the places where policy has to be affected. The central government has very little control over what they actually do in the provinces, what monies they appropriate to affect laws, so there’s a real disconnect. It’s sort of an area where authoritarianism doesn’t work as well as it might. This is where regional power is accrued, but to the harm, I think, of the common wheel. So that’s a real problem.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Will there be positive movement in the rule of law?

ORVILLE SCHELL: I think expanding the rule of law is in a state of some suspension right now. It has sort of gotten to a certain point and it has run into conflict with the party’s instinct to control, and the law’s an independent power center and can sometimes be very threatening. So I think that’s part of the reason we have this feeling that something’s got to change, that things have come up against the end of an evolutionary phase in their present scheme of things. You can identify many, many other fronts where this is also true.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: So Xi Jinping has got to move quickly, consolidate his power, and figure this out?

ORVILLE SCHELL: Hu Jintao was lucky to get out of there before the roof fell in, if it’s going to fall in. Xi Jinping has an incredible challenge ahead of him: somehow, not only to keep China from unraveling, but to keep pushing it forward. And, he must do all this at a time when there’s all of this emphasis on not rocking the boat. Deng Xiaoping rocked the boat. But he had a certain, you know, droit du seigneur. He had greater latitude to do what he wanted. In key ways Xi does not have this mandate.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: Although Xi Jinping has a bit of that feeling about him. I’ve been struck seeing him speak at how confident he seems. He’s not reading from a prepared text, and all that stuff.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Well, we will see what he can get away with. If he did prove to be very bold and forward, it will all make sense we’d say, “Oh, yes, and his father, and this and that.” If he can’t, we’d say, “Alright, it makes sense, he just couldn’t do it. The leadership is now too timid, consensual, and paralyzed.”

DORINDA ELLIOTT: His father, Xi Zhongxun, having been stationed on the east coast, pushed reforms, economic reforms, and export economy, and not only that, but he allegedly came out and criticized the crackdown in 1989. So in theory, his father was a real kind of liberal reformer.

ORVILLE SCHELL: Well, in theory more than “in theory,” Wen Jiabao was with Zhao Ziyang his last night in Tiananmen Square. There are a lot of theories that seem to get trumped by the reality of the power-sharing system. Xi Jinping is like a stem cell. He hasn’t developed yet into any discernible organ, or any discernible tissue. And the amazing thing about Hu Jintao was, ten years later, he hadn’t yet either. But, we do not yet know what Xi Jinping may yet become and what political views he may be able to express and act upon.

DORINDA ELLIOTT: How old do you have to be in China to be allowed to actually be yourself?

ORVILLE SCHELL: That’s why I say, I’ve waited through probably three or four generations with people always telling me, “Wait for the next generation.” The next generation comes and things do change, but what is equally as amazing is what has not changed. Truthfully, I don’t know where things are going. In China, things are always going in opposite directions at the same time. And there is no understanding the place, unless you can embrace such contradictions in your head at the same time.

Dorinda Elliott is the global affairs editor at Condé Nast Traveler. She was a correspondent atNewsweek from 1985 to 2000, serving as bureau chief in Beijing, Moscow, and Hong Kong. She was editor-in-chief of Asiaweek from 2000 to 2001, and an editor-at-large and assistant managing editor at TIME from 2003 to 2006. She was the recipient of an Overseas Press Club award in 1996 and 1997 for her reporting on China.