Trump’s Dangerous Gamble

The consequences of Trump’s short-sighted decision on the Iran Nuclear Pact and an analysis of the JCPOA’s pros and cons.

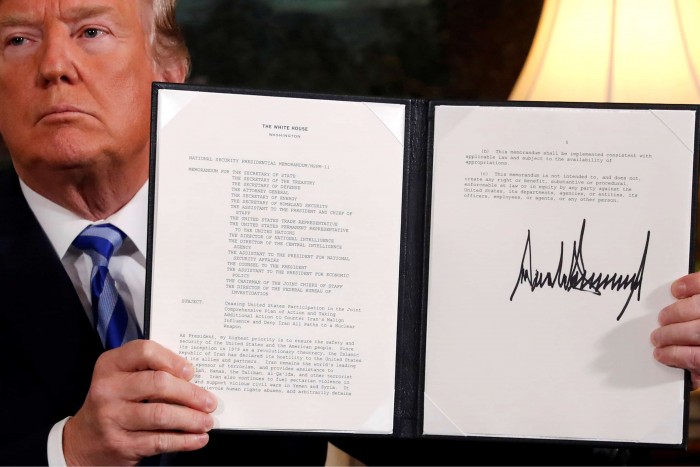

U.S. President Donald Trump holds up a proclamation declaring his intention to withdraw from the JCPOA Iran nuclear agreement after signing it in the Diplomatic Room at the White House in Washington, U.S. May 8, 2018. Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

In what could be the most consequential decision thus far of his chaotic Presidency, Donald Trump has withdrawn the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). There was no compelling reason for this action now, beyond ideology and his unshakable belief that he can “do better” than anyone else when bargaining.

Much that has been written about this decision is informed by the ideological views of the authors. The JCPOA was either a “historic mistake,” which Trump has courageously scrapped in order to protect the region and the world from Iran’s nefarious long-term designs, or the JCPOA was the best deal possible under the circumstances, which promised the region at least a decade of respite from this dangerous issue. Lost in much of this discussion are the facts.

The JCPOA effectively halted Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program. It required Iran to divest itself of 98 percent of its stocks of enriched uranium; dramatically reduce its enrichment activities; permanently disable its plutonium production capability (the “other” route to a bomb besides enriched uranium); and subject itself to the most intensive on-site inspection regime any country has voluntarily accepted in the history of non-proliferation. In return for this, Iran receives relief from economic sanctions.

The JCPOA contains “sunset” clauses, whereby certain provisions will lapse over a period of time, beginning ten years from the date of signature and extending out to twenty-five years from signature. However, what will never be removed, if the deal survives the U.S. departure, are key parts of the agreement, including the verification provisions. So what arguments did Trump and his supporters use to justify their actions?

First and foremost, they pointed out that the deal does nothing to constrain Iran’s missile research, or its regional activities, which are of concern to many (support for the Assad regime, support for terror groups, etc.). This is true; but the JCPOA was not designed to deal with those issues. At the time the JCPOA was negotiated it was decided that the key issue was Iran’s nuclear program and that needed to be contained. There are, in the meantime, other sanctions programs designed to deal with Iran’s missile research and development.

Second, there have been dark murmurings from certain corners that Iran has been cheating. To this point, all of the authorities charged with monitoring the JCPOA are agreed that Iran has lived up to its commitments. The new U.S. Secretary of State supported this view in his recent confirmation hearings. The other signatories to the deal (China, France, Germany, Russia and the UK) are also agreed. Even the deal’s harshest critic, Israel, has not provided proof of cheating, beyond re-hashed allegations which do not stand up to scrutiny. Indeed, many senior Israeli security officials, both serving and retired, have stated that the deal is working and is in Israel’s interests.

Third, the so-called “sunset” clauses have come in for much comment. As noted above, these are only partial and much of the deal is set to remain in effect permanently. Moreover, the clauses that are going to sunset are not due to begin to be lifted for many more years—so there was no urgency in scrapping the JCPOA right now on this score. Even if one believed the sunset clauses were a fatal flaw, they do not begin to become a real issue for several years—more than enough time to work within the agreement to find answers and still retain the ability to leave later if necessary.

One can only conclude that Trump’s actions have little to do with the objective realities of the JCPOA. Instead, his actions appear motivated by a combination of ideology and hubris. The ideology is that Iran’s theocratic regime is simply unacceptable and must be done away with. No deal is therefore possible unless its terms are so far-reaching as to effectively cause Iran to cease to be the country it presently is. The hubris is Trump’s apparently limitless faith in his ability to leverage others to do his bidding.

Of course, it is entirely possible that there is no long-term thinking here. President Trump has shown a penchant for embracing chaos—for throwing all of the balls into the air and counting on his skill as a negotiator to manipulate fast-moving and unpredictable events to his advantage. If that is what he doing, he is taking a big risk.

Perhaps most importantly, Trump’s actions do not simply repudiate Iran; they also repudiate the other signatories to the deal—which include some of America’s closest allies, all of whom counselled, both privately and publicly against leaving the deal—and the entire international non-proliferation system.

Key to the success of Trump’s strategy, to the extent he has one, is the re-imposition of crippling sanctions on Iran. These existed before the JCPOA was signed and were a large part of the reason the negotiation succeeded. It seems unlikely that Trump will be able to put together the international sanctions coalition which existed previously, as many of its key members are those he left in the dust by unilaterally leaving the JCPOA. Trump can use provisions, which enable the United States to penalise those who trade with Iran, but this will only further strain relations with key allies and will not be effective against those immune to such pressures.

Meanwhile, unless the other members of the JCPOA can save the deal, Iran is now free to resume its nuclear activities and is largely outside the shadow of international sanctions. For the hardliners in Tehran, this can only be considered a win. For any other country considering making a deal with the United States on a matter of survival, those who counsel that Washington does not keep its word have been strengthened in their arguments.

For the rest of us, the region and the world have become less predictable, more dangerous places.

Peter Jones is associate professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. He previously held several positions relating to international security matters in the Privy Council Office (the Prime Ministers’ Department) and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs. He has been active, both as an official and as a practitioner of Track II negotiations and discussions relating to Middle East security over twenty-five years.