Arab Reform and Revolt

Economic reforms are a necessary step, but not enough to save ailing governments.

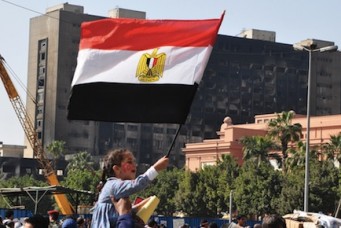

Egyptians scramble to buy government subsidized sugar in Cairo, Oct. 14, 2016. Amr Abdallah Dalsh/Reuters

After years of hesitation, several Arab countries are enacting economic reform measures, typically in conjunction with financial support programs from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The measures entail rapid reduction of energy subsidies, significant increases in electricity and water tariffs, major reductions in the state’s commitment to public pensions, and concerted efforts to make the country’s financials sustainable, which means reducing the recurring need to borrow (locally or internationally) to meet state obligations. The most recent example is Morocco’s full liberalization of petrol prices and Egypt’s floating of the pound and significant reductions of fuel subsidies.

Invariably these measures stir debates—and fears—about the political costs the authorities could pay. Observers speculate about the prospects of social unrest and waves of protests that could threaten the ruling regimes. Egypt’s January 1977 bread riots, when tens of thousands of protestors took to the streets rejecting the increases in the prices of basic goods, prompting the authorities to immediately reverse these price hikes, are usually invoked as a classic example.

Following the 2011 Arab uprisings, most Arab authorities are now versed in how to respond to the first signs of large-scale demonstrations, whether through tactical use of force, media messaging, or infiltration of crowds. But protests are different from political revolts, which could come in the form of demonstrations, unexpected voting patterns, or widespread acts of violence perpetrated by large groups of people.

Irrespective of the form they take, revolts typically do not stem from economic difficulties, but when people feel—for a significant period of time—that the future holds no promise for them, and that economic difficulties will settle in and become the norm and their future will be worse than their present. Revolts come when people feel that their dignity is trampled on. Political rhetoric and media manipulation could assuage that feeling for some time. But as lifestyles deteriorate, aspirations crumble, and large sections of the middle class spend months on months pulling immense effort to barely afford the basic necessities they used to take for granted, their sense of dignity takes a severe blow.

The deterioration of public spaces contributes to the build up of pressure. Universities, professional syndicates, libraries, social and sports clubs, entertainment centers, and even safe areas for ordinary citizens to gather (for example, parks) allow for healthy social interactions, the development of a plurality of ideas and viewpoints, and the subtle but important feeling that individuals relate to the society’s commons, and to the overarching whole that brings all together. These feelings lessen the build up of anger. Such public spaces, and the feelings they engender, have been acutely suffering in most Arab countries for at least two decades.

Religion used to be a hedge against revolts in the Arab World. Largely pious and conservative, Arab societies have, for centuries, relied on religion to soothe and console. Arab political elites have also relied on religious (Islamic and Christian) institutions, which traditionally command colossal reverence, to act as bulwarks of stability against the “peril of unrest and sedition.” But the role of religion in Arab societies, for over a decade now, has been undergoing a subtle but important change. Large sections of young Arabs (the significant majority in all Arab societies) are experimenting with new definitions and understandings of the role of religion in society: as a basis for legitimacy, identity, legislation, and frame of reference. This is coupled with a major dilution in the prestige, reach, and influence of most leading religious institutions across the region.

There is also a sense of injustice prevalent in many Arab societies. In some cases, this is a result of historical situations: certain sects have lesser rights than others or regions were intentionally ignored from investment and development plans. But often injustice is the outcome of corruption and acutely dysfunctional political-economy structures whose function is to perpetuate the conditions through which ruling elites reign. In these situations, people feel that the “system” is not only faulted, but that it is working against them.

These factors take a long time to simmer. When they are ripe they give rise to revolts, whether or not in the form of demonstrations.

Revolts bring together social constituents with different and often opposite objectives, but who share common feelings of exasperation, frustration, and rejection of the order in place. This is conspicuously clear now in the various groups that support the extreme right in Europe, which irrespective of cultural background feel that their economic futures are bleak, sense (or imagine) a considerable change in their social milieu (caused by immigration), and who feel the elites have not only created these conditions they are in, but have gotten away with crashing the system (whether in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008 or the steady but clear decline in European lifestyles in the last decade).

In the Arab World, there is an added factor that could make any coming wave of political revolt much more acute than in Europe. The failure of what used to be called the “Arab Spring” has sapped the will for smooth change from the most promising and socially engaged young Arabs. Political initiative now resides with groups that are much less educated, sophisticated, and intellectual.

In revolts, persuasion loses currency. The loss of respect for the prevailing order, for state institutions, and for the notion of stability, descends segments of society into their most basic elements. This is why revolts trigger raw feelings: whether powerful aspirations for change (which could be constructive), or desires for revenge, and often destruction. The underlying driver here is insecurity, the product of all these feelings about the deteriorating lifestyle, worse off future, and sense of injustice.

It is impossible to predict when will the accumulated pressure give way to the first expression of revolt. Political economists have learned to respect the immense wisdom of the law of unintended consequences. As the leading technologist Andrew Grove once put it (in an entirely different context): “factors accumulate and lead to a strategic inflection.”

From this perspective, economic reforms should not necessarily trigger fears of unrest, because even if they create economic difficulties, they are a momentary factor. Actually, if coupled with serious improvements in political, civil, and human rights, and in governance, such comprehensive reform could defuse negative feelings and convictions that have been accumulating for years. Such comprehensive reform could become the basis for a new, sustainable, and mature state-citizen relationship. This is a reason why theorists of transition (towards advancement and sustainable development) couple economic with political reform. The problem occurs when economic difficulties become another layer of pressure in a construct decaying from anger and anxiety. For if economics is the sole pillar upon which a state builds its new social contract, the new construction won’t withstand the forces of rejection that have been growing for years, and that could come crashing in.

Tarek Osman, a political economist and broadcaster focused on the Arab and Islamic worlds, is the author, most recently, of Islamism: What It Means for the Middle East and the World.