Drafting Constitutions

Toward Liberty, Justice, and Human Dignity.

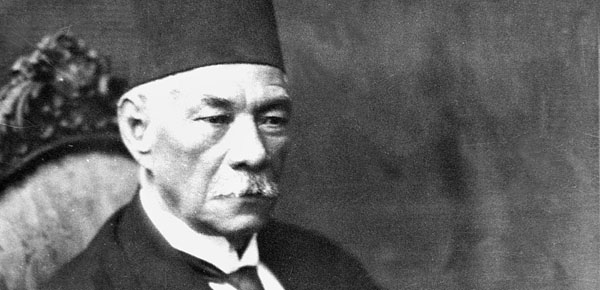

Egyptian independence leader Saad Zaghloul, circa early 1920s. AFP/Getty Images

A TV show recently invited me to talk about the history of Egyptian constitutions, and the lessons we can draw from this history in our efforts to draft a new constitution. I was immediately struck by how little I knew. We were taught nothing about our constitutional rights in civics classes in school, and our history classes stressed the victories of our nation rather than our rights as citizens.

So, I have been struggling to catch up. I learned from a colleague, for example, that the so-called liberal constitution of 1923 had many non-liberal features. It was written in the wake of the popular 1919 revolution, which had been ignited by the British arrest and exiling of independence leader Saad Zaghloul. Many of Egypt’s best legal minds served on its drafting committee, and Zaghloul would become the first prime minister under this constitution. Yet it was also written under the tutelage of an oppressive colonial occupation. The constituent assembly that drafted the constitution discovered that a Consultative Committee for Legislation staffed by British administrators and mandated to “revise” the draft ostensibly on technical grounds only, actually exceeded its mandate. It had tampered both with the text and spirit of the draft, and inserted many clauses that curtailed basic freedoms and rights, most importantly those of free speech and free assembly.

I also learned that the constituent assembly that drafted the 1971 Constitution was stunned to see that the text they had presented to President Anwar Sadat after months of careful preparation had little connection to the one that was eventually presented to the people to vote on in a national referendum. Sadat, victorious from his power struggle against Nasser’s men, had managed to alter the draft, and the final text reflected the expansive presidential powers that he’d won from his enemies—powers he wanted enshrined in the constitution.

Considering these precedents, I fully appreciate this current truly historic moment. Never before have we, the Egyptian people, been given the opportunity to write a constitution following a popular revolution. We have no British occupying power to dictate to us how we should manage our country, nor a tyrant who wants to twist the constitution to protect his privileges.

Our revolution deserves a revolutionary constitution, one that reflects the positive, self-confident mood of the millions who made it happen. We expect our new constituent assembly to enshrine in our constitution the principles that inspired our revolution: liberty, justice, and human dignity. Rights such as free speech, free belief, public assembly, and gender equality, among many others, should be expressly stated in the constitution in a clear, categorical way that is not open for subsequent curtailment by executive fiat or legislative act.

Like all revolutions, ours is a messy one, and we are realizing how much more difficult it is to build a new system than it is to bring down an old one. Moreover, our revolution has not yielded a clear winner. The political scene is suffering from a division among three main camps: the remnants of the old regime, the feloul, who, together with the army and the institutions of the ‘deep state,’ did badly in the parliamentary election, and whose candidate, Ahmed Shafik, lost the presidential election; the Islamists, who won a huge majority in the parliamentary election and whose largest faction, the Muslim Brotherhood, succeeded in winning the presidency for its candidate, Mohammed Morsi; and finally, the revolutionary forces who triggered Egypt’s revolt but whose lack of organizational structure resulted in their losing both the parliamentary and presidential elections.

Each of these three forces has different expectations of the constitution. The remnants of the former regime, most notably the army, managed just a few days before handing over power to the elected president, to insert into the constitution such language as to protect its significant privileges and effectively establish the army above the law and the constitution. The Islamists, for their part, believe deeply that their victory in the parliamentary election gives them a mandate to implement Islamic law. Finally, the revolutionary forces are determined that the coming constitution should defend the ‘civilian’ nature of the state, insisting that the Arabic word for civilian, madaniyya, is symbolically both non-military and non-religious.

Interestingly, the protracted struggle surrounding the formation of the constituent assembly did not reflect this tripartite division—it was merely a bipartite one. The key issue was whether or not the constituent assembly should include elected members of parliament. Given that Islamists had won some 70 percent of parliamentary seats, non-Islamists were anxious that allowing MPs to elect themselves to the constituent assembly would result in an Islamist domination of the constitution-drafting body. There was also the question as to whether or not the Islamists were correct in their argument that winning the parliamentary elections actually gave them a mandate to write the constitution. After the Supreme Constitutional Court dissolved parliament on a legal technicality and the Administrative Court also dissolved the first constituent assembly, Egyptians are currently preoccupied in debating the ideal ratio of Islamists versus non-Islamists in the assembly.

There is no doubt that public concern about the religious leaning of the constituent assembly is an important one. But a more important question surrounds the very nature of the constitution. Should it be a document that merely reflects society as it is? Or should it strive to draw a picture of society as it should be? Should our constitution refer to the values, common beliefs, history, and past struggles of the Egyptian people? Or should it, rather, aspire to a society that we still do not have, to dreams we cherish, to values that we need to inculcate, and to hopes we want to achieve?

Any constitution should strike a balance between the shared values of a people as they are, and their common image of themselves as they wish to be. Accordingly, the question should not be “What is the religious persuasion of the members of the constituent assembly?” but, rather, “Are they simply drafters who translate the shared values of the Egyptian people into constitutional texts, or are they visionaries who can transcend the lowest common denominator and aspire to loftier goals agreed upon by few but dreamed of by many?”

Our revolutionary moment requires us to abandon the “Islamists versus non-Islamists” criterion when thinking of how to form our new constitutional assembly. We should ask whether our new constitution should be written by drafters or by dreamers.

Khaled Fahmy is a professor of history and the chair of the History department at the American University in Cairo. He is the author of several books, most recently Mehmed Ali: From Ottoman Governor to Ruler of Egypt. He has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, andWashington Post, and contributes regularly to the Egypt Independent.