Egypt’s Democratic Triumph

Mohammed Morsi’s victory over Ahmed Shafik in the Egyptian presidential election is a political triumph for the Muslim Brotherhood, a banned organization for most of the years since the country became a republic in 1953. It is likewise an important victory for Egyptian and Middle East democracy. Having edged perilously close to the brink of political chaos in recent weeks, due to repeated bungling of the transition process, Egypt has taken a very significant stride forward.

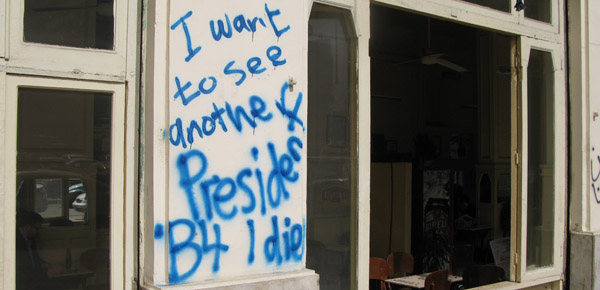

Street graffiti, Cairo, Feb. 22, 2011. Scott MacLeod for the Cairo Review.

Mohammed Morsi’s victory over Ahmed Shafik in the Egyptian presidential election is a political triumph for the Muslim Brotherhood, a banned organization for most of the years since the country became a republic in 1953. It is likewise an important victory for Egyptian and Middle East democracy. Having edged perilously close to the brink of political chaos in recent weeks, due to repeated bungling of the transition process, Egypt has taken a very significant stride forward.

Morsi and his group have earned a substantial role in Egyptian public life. The Muslim Brotherhood has borne the brunt of state repression throughout the regimes of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak. Its leaders and members persevered against difficult odds. They managed to create a strong grassroots movement that provided social services and gave a voice to the voiceless. They provided some hope during long, dark years when Egyptian presidents offered none. In the face of intolerable state violence spanning decades, the Brothers remained tolerant. They eschewed violence and exhibited super human patience.

Thus, for Morsi, a U.S.-educated engineer, and the Brotherhood, the results are a spectacular political achievement, attached with profound symbolism. After 60 years of military rule upholding secular values, Egypt has elected the first civilian president in its history, and its first Islamist president, too. Morsi’s victory is testimony to the Brotherhood’s ability to mobilize Egyptians against a deeply entrenched political system, and to convince Egyptians that its candidate was the most capable of taking the helm after Mubarak’s removal from power. If it rises to its responsibilities, the Brotherhood can be the hope of Egypt and of the Arab Spring.

The reason why Morsi’s win is also a triumph for Egyptian and Arab democracy is because of the critical, historic choice it represents. When Egyptians went to the polls in the June 16-17 runoff election, they were not primarily voting between a military candidate and an Islamist candidate. They were choosing between the past and the future: a continuation of the 60-year-old Egyptian military regime, or a new system built on genuine democratic participation.

Shafik is a man of doubtless abilities, having served as air force commander, minister of civil aviation, and, finally, as Mubarak’s last prime minister. Yet, Shafik’s resume was more a liability than an asset in a country raising thundering demands for change. The millions who chose Shafik wished that his iron fist and close ties to the military could restore stability. His supporters are disappointed by the results, but that is nothing compared to the rage that would have been expressed by millions of Egyptians demanding an end to six decades of military rule if Shafik had won. At worst, the perception of an election stolen by the military might have edged Egypt toward an Algeria scenario; that country experienced a terrible civil war triggered in 1991 when the military abruptly canceled elections Islamists were poised to win.

By contrast, the Morsi victory is the kind of outcome that elections in a democracy are supposed to produce-a winner who finds himself in a political arena that promotes and requires negotiation, compromise, concession and conciliation for the greater good of the nation. During the previous era, when Mubarak regularly received 90 percent of the votes, elections were nothing more than a farcical means of legitimizing the continuation of a state security regime. Any negotiation with other sectors of society- it occurred rarely-was on the regime’s terms. That is what led to the absolute ossification of Egyptian life, and, eventually, a revolution.

Instead, Morsi and the Brotherhood will find themselves in perpetual negotiation with all of Egypt’s players-with the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, Salafists, Coptic Christians, liberals, and even with Shafik and his supporters. The process formally began last week, when Morsi announced the formation of a national political front and proposed the establishment of a national unity government. These moves underline the Brotherhood’s understanding of democratic concepts like consensus building and inclusiveness.

It is clear to most Egyptians that Morsi is doomed to fail if he turns out to be a president who represents only the Brothers. Or, if he thinks the Brotherhood could or should somehow hijack a revolution that involves a wide cross section of Egyptians. Many Egyptians have serious and valid questions about the Brotherhood’s abilities, policies, and intentions-on issues from women’s rights and the role of religion in the state to readiness for foreign investment and other forms of cooperation with outsiders. (Let’s not forget, though, the problems Egyptians had with the former regime that led them to revolt last year-political repression, police torture, corruption, appalling medical care, horrendous education system, the list goes on.)

The importance of representing all Egyptians can’t be lost on Morsi or his group’s strategists. In the parliamentary elections earlier this year, the Brotherhood’s political arm, the Freedom and Justice Party, garnered an impressive 10.1 million votes. In the first round of presidential balloting just five months later, however, Morsi, the Brotherhood candidate, won only 5.7 million-a downward slump indicating strong disillusionment with the Islamists’ performance in office. If we suppose that those 5.7 million voters constitute the Brotherhood’s core of diehard support, then Morsi’s 13.2 million total in the runoff election means that he gained the backing of 7.7 million Egyptians who can easily desert the Brotherhood and vote for an alternative the next time.

Morsi will need all the negotiating and consensus building skills he can muster in the weeks and months ahead. Despite Morsi’s victory-and SCAF’s evident and necessary acquiescence in allowing it to stand-Egypt’s revolution is hardly finished. The ruling generals are showing extreme reluctance to hand over power to elected civilians by July 1 as they once pledged to do. In the midst of the presidential campaigning, SCAF enforced a court ruling dissolving the Islamist-controlled parliament, issued a decree granting the military executive powers and sharply curbing the authority of the new president, and gave itself a central role in approving a new constitution being drafted by a 100-member constituent assembly. Morsi’s challenge is to use his powerful mandate as Egypt’s first popularly elected leader to guide all Egyptians, including the reluctant generals, into a democratic future.

This article originally appeared in the Huffington Post.

Scott MacLeod is managing editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs and is a professor in the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the American University in Cairo