Imagining a New Arab Order

The Arab World is witnessing ideological, sectarian, and ethnic conflicts. A new Arab order will emerge out of these ruins, but it will take time.

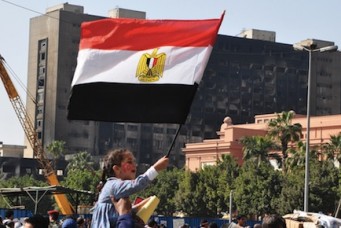

World Map, by Hamza Serafi, Jeddah, January 23, 2012. Susan Baaghil/Reuters/Corbis

The Arab World is witnessing ideological, sectarian, and ethnic conflicts. The region has not experienced such polarizations in at least a century. As governments are no longer serving as arbiters among competing interest groups, the state has lost legitimacy. Violence is on the rise across the region. Politics have become highly militarized, and state-sponsored killing is a common phenomenon. Several countries have turned into mere spoils of war that various factions are fighting over, with utter disregard for citizens’ futures. The incentive of groups to stick together has been dramatically decreased.

A new Arab order will emerge out of these ruins, but it will take time. In the medium term, some countries will be consumed by internal conflicts. Central authority has already been lost in Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Kuwait and Lebanon face acute strains on their social fabrics. Algeria will soon confront turbulence; the looming death of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika will give way to a power struggle. Others will be divided into sub-regions that gradually detach themselves from the Arab World (for example, South Sudan and Kurdistan). New statelets will forge links to Africa and Asia. As a result, the Arab World will shrink.

There is a dearth of solutions to these crises. The administrations of large Arab countries have adopted a paternalistic style of governance. Saudi Arabia, in particular, has anchored its legitimacy through assuming the role of provider, effectively buying off the middle class. Their religious allies assert the concepts of “the general will” and “obedience to the ruler.” These strategies will backfire. As oil prices drop—likely stabilizing at much lower levels than the past decade—massive social welfare programs will prove unsustainable. More importantly, this paternalism antagonizes large segments of youth who are more educated, economically independent, socially entrepreneurial, and globally aware than any previous generation of Arabs.

Regimes learned the wrong lessons from the uprisings. Arab states have perfected their dominance of television stations. In the Middle East, this is the most powerful medium for mass communication given dismal illiteracy rates that exceed 40 percent. The political elite has mastered the atmospherics of statements that influence public opinion. But there is no content. With a few exceptions—such as the energy-reforms in Egypt and the regionalization drive in Morocco—there is an alarming lack of ideas about how to tackle the Arab World’s social, economic, and political problems.

Especially startling is that regimes are sidestepping the biggest issue: lack of competitiveness in the local and global marketplace. A significant percentage of the 180 million Arabs under 35 years of age are hardly suited for today’s job market. Putting aside multinational companies, many Arab youths are increasingly unemployable in their countries’ private sector. As states face the impossibility of providing for destitute populations, the majority of young Arabs will be temporary workers in cyclical industries, such as construction and tourism. Incomes will freeze as prices rise, and many countries will increasingly be reliant on market forces for energy and food, and potentially water. Substantial groups of young Arabs—especially among the well-educated—feel trapped by their governments’ lack of imagination.

Similarly, the opposition has failed to put forward new ideas or policies. The parties of the previous half century—whether liberal, nationalist, socialist, or centrist—perpetuate tired rhetoric. Aged figures with questionable credibility continue to lead opposition parties across the region.

Anger will swell. Expect another round of mass demonstrations in various parts of the Arab World, even in countries that seem stable today. Sections of the middle class will join forces with the poor and frustrated. This is already leading many Arab activists to explore new parameters for challenging regimes. As most of the 2011 uprisings have failed, several Arab youth groups believe that peaceful mobilizations will not affect the transformative change they seek. Some have already acquiesced to the idea of using violence against entrenched powers. This is one of the key factors fuelling the confrontations we are seeing in parts of North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. Militarized activism, coupled with the states’ militarized exercise of power, will result in the spilling of much more blood.

Amid these developments, four things have been lost. First, most Arab states have wasted the opportunity to undergo peaceful transitions. Evolving gradually—expanding what has been familiar—is no longer a choice. Now, governments must explore unchartered and dangerous transformations. Second, the Arab World has lost much of its societal and institutional expertise, which was accumulated over the past decades. It is a monumental loss. A brain drain has resulted from the descent into civil wars, the dramatic rise in violence, and the disconnect between states and their youth. Third, the most ethnically and religiously heterogeneous Arab societies, notably in the eastern Mediterranean, have forgone any chance of peaceful coexistence, at least in the short to medium term. Finally, in several parts of the Arab World, the state’s moral authority has simply crumbled.

We have been here before. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman and Mamluke authorities lost their grasp of power as their citizens faced with European modernity for the first time. The elite and the upper middle-class were shocked by the gap between them—the deficits of their means and knowledge—and that of the West. Modernization projects altered the economic and social structures of Arab societies. The reforms that Sultan Selim I and later Mahmoud III had introduced in Turkey in the mid-nineteenth century shifted the Ottomans’ focus from the Arab World to Europe. Political voids appeared in Algeria, Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, Egypt, Greater Syria, and Tunisia. Social tensions came to the fore and erupted into bloody confrontations, notably the 1860’s civil war in Mount Lebanon between the Christian Maronites and Muslim Druze.

The collapse of the old order brought the rise of regional powers. The Albanian political adventurer Mohammed Ali, for instance, took control of the entire Nile valley. The large central Arabian family, the Saudis, revived an old alliance with the conservative Islamic Wahhabi sect; together they asserted control over the Arabian Peninsula. The Moroccan Alawite royal family expanded its rule south toward the Islamic parts of Africa’s west coast. A few decades later, the Hashemites leveraged their descent from the Prophet Mohammed to claim new kingdoms that, for a period of time, dominated the entire eastern Mediterranean. In very different ways, the four dynasties established order through centralizing political and economic power in much of the region.

A second response to the collapse of the old order came from external powers. Britain, France, Italy, and Spain occupied parts of the Arab World. This was another consolidation project, albeit with different objectives and structures.

Today, no regional or external power has the resources to attempt a consolidation project over any sizable part of the Arab World. The rich Gulf dynasties realize their limitations and exert their influence selectively. The Egyptian regime faces acute social and economic challenges, which is why Cairo will look inward in the short to medium term. Algeria and Iraq have the financial resources and demographic gravity to play a regional role; however, the former is consumed by sectarianism, and the latter by a complicated political succession as well as the ghosts of a civil war. Morocco aims to deepen its connections to Europe as well as to evolve as West Africa’s economic, financial, and cultural hub, with limited connections to its Arab neighbors.

Without forward-looking consolidation projects, the Arab World will likely disintegrate. Some countries will drift away from the Arab system; others will be divided along tribal, sectarian, and entrenched loyalties. Many Arab countries will undergo a process of Lebanonization. They will have nominal political systems with tenuous power. Wealthy regions or social groups will isolate themselves economically, while continuing to pay lip service to the central authority. Non-state actors will gradually build capabilities to challenge, and thus deter, the central governments.

Will these patterns of disintegration devastate the Arab World? I would argue that this disintegration will evoke new ideas and ideals.

Arab youths, especially within the middle class, will be most affected by these changes. They are currently marginalized; they are afraid to get caught in increasingly militarized politics; they are also leaderless and poorly organized. Over time, clusters of young Arabs will overcome their fears and organize themselves into powerful political and economic groups. They will seek ways to shape the very notions of stability, economic progress, and social harmony. They will generate new views, socio-political structures, even social contracts.

Amid this forthcoming awakening, two value systems will underpin young Arabs’ thinking. The first will be championed by the religious, drawing on the conservative cultures of large agrarian and desert countries (primarily Egypt, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia). This will propel a new type of Islamism, likely more conservative than that since the 2011 uprisings. Having witnessed the havoc that jihadist groups such as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria have wrought, this Islamist current will be peaceful yet assertive and uncompromising. It will invoke strict Islamic identity and sharia as the only solution for rescuing the Arab World from chaos and disintegration.

Other groups of young Arabs will be inspired by the maritime trading cultures of the Levant, Maghreb, and small Gulf states. This liberal current will distance itself from twentieth-century Arab Islamism as well as from the heritage of Arab nationalism of the past seven decades. Yet, the secularists will also be forceful. They will aim to repeat the Arab liberal experiment of the early twentieth century, but without too many considerations for the sensitivities of their conservative or nationalistic counterparts.

New Islamists and new secularists will make the case for surmounting decay. Both groups will be disillusioned by the regimes that have failed to stem the Arab World’s degeneration.

A war of ideas will ensue. The two sides will try to salvage the Arab World through political activism, working to advance economic reforms and social entrepreneurialism. Both will fail to ascend to their envisaged ideals. Energy and resources will be wasted. But it will be a rich period in Arab history. Because these movements will emerge from a period of disorientation and disintegration, their confrontation will remain political and intellectual. Arab politics will gradually be de-militarized. This will lead to maturity. The two movements will evolve beyond their original forms, mixing and borrowing from each other.

It will be a long, difficult, and costly decade or more. The Arab World will emerge from it smaller and poorer. Yet this long process will be the Arab World’s catharsis. Long-chained demons will finally be released. The result will neither be a Western-style liberal democracy nor a Turkish-style Islamist one. Rather, we will see different blends of the Islamic, secular, and nationalist ideas.

After this cathartic period, there is a strong chance that the secular current will overpower the religious. Among the factors in the former’s favor: Arab demographics; the steady rise of the Arab private sector; social entrepreneurialism; technological changes in communication and exposure to the world; and the slow evolution of the thinking, rhetoric, and way of operations of state institutions in the conservative Arab cultures.

Following this tortuous journey, the Arab World will move slowly towards liberalism. This could put an end to the current plundering of Arab heritage, and to the suicidal reduction of modern Arab history into meaninglessness.

Tarek Osman is the author of the international bestseller Egypt on the Brink.