Regional Conflicts Bleed Into Yemen’s War

Along with Saudi Arabia and Iran, Hezbollah and the U.S. risk being pulled further into Yemen’s civil war.

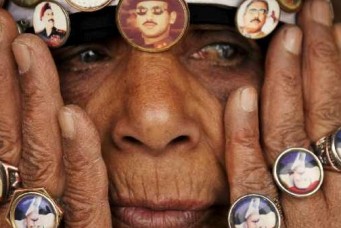

In a speech he gave on the occasion of the tenth of Muharram (Ashura), the leader of the Lebanese organization Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, made a blistering attack on the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for its bombing of a funeral gathering in Sanaa on October 8, and warned his audience that the regional situation was very tense with only military escalation in the air. On Yemen specifically, he said that the world must convince Saudi Arabia that it cannot win this war, as the “noble Yemeni blood would emerge victorious.” He added that not only would the kingdom lose the war but it would also “lose itself in the process.”

Nasrallah, an astute observer of regional politics, is not known for hyperbole nor for empty boasts. His warnings, usually signaling impending action, can in this case be taken to mean steadfastness for his support for the Bashar Al-Assad regime in Syria, stepping up aggressively his support to Yemen’s Houthis, and possibly engaging in covert action against Saudi Arabia.

The region is indeed getting more tense by the day. In Syria, Aleppo is about to be obliterated as the two great powers bicker, exchange accusations, and even threaten one another. The Yemen war grows more intense with the Houthis firing rockets ever more deeply into Saudi Arabia, while U.S. and Iranian naval vessels are circling each other menacingly in the Red Sea and the Gulf. Add to that an American presidential campaign that gets more bizarre and chauvinist by the day, and the signs are all ominous for the Levant and Gulf sub-regions of the broader Middle East.

A sequence of events over the past few months indicate a troubling trend.

In August, the Kuwait peace talks looked promising for a few weeks, but the United Nations envoy gave a break to participants saying he expected them to return with implementation steps of the ideas he had suggested. The government of president Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi was quick to denounce the UN envoy saying that they had not agreed to his proposals and would not therefore be presenting any such steps. Even though the general framework for an agreement has been there for months—specifically, a Houthi withdrawal from the capital in return for a transitional government and a path forward to a more representative cabinet than the current one—the parties have remained stubborn on the sequence of steps required. The Houthis want the transitional government in place before they hand over any heavy weapons and leave Sanaa. Hadi’s government wants Houthis to leave Sanaa before Hadi, as president, convenes a transitional government. This chicken and egg game is likely to hinder any breakthroughs at the meetings now proposed by Oman and endorsed by the U.S. and the UK at a recent meeting between John Kerry and Boris Johnson. The balance of power on the ground remains essentially the same since the early phase of the war last year, with advances by pro-government forces weakened by fissures in the southern front and countered by Houthis crossing the international borders with Saudi Arabia in the north. Each side still hopes to prevail militarily and has therefore been reluctant to offer any real concessions.

The bombing of the funeral gathering in Sanaa was probably the worst death toll in any one incident since the Saudi Arabian air war began eighteen months ago. Denying at first that any of their aircrafts had fired the rockets, the Saudis a week later, and after initiating a multinational inquiry, admitted that indeed it had been their air force, and that it was a “mistake.”

Incredibly, the Saudis declared that their pilot fired based on “faulty information” that the gathering included a large number of Houthi leaders. Blaming Yemeni allies for misdirecting their fire was hard enough to believe. Even more outrageous was the suggestion that a gathering of Houthi leaders—obviously not in the midst of a battle—was considered a legitimate target to bomb.

Needless to say, this elicited cries for revenge not only from Houthi hardliners, but from ordinary Yemeni citizens who lost loved ones in the attack.

Even before this incident, Houthi sympathizers had been calling the air attacks a joint Saudi Arabian-American campaign. The United States, conscious that it was implicated in the international outcry against Saudi Arabia, withdrew from Riyadh most of its military personnel dedicated to supporting the war in Yemen. Nonetheless, the missile attack on the USS Mason, on October 9, was perceived by many as retaliation by the Houthis against the United States, even though the Houthi leadership denied having fired on the ship.

Rockets fired at the USS Mason came at an inopportune time for those in the Houthi camp who believe in ending the war as soon as possible. That the U.S. Navy would fire back is normal enough. The concern is that Washington, which had been considering ending its support to the Saudi Arabian war effort, might now rule out such a change in policy and choose instead to teach Iran—the presumed instigator behind the rocket attacks—a lesson on not threatening the international waterway of Bab El-Mandeb. Iran has now dispatched it own naval vessels to the Red Sea, sending a counter-warning to the U.S. not to engage directly in fighting the Houthis.

The U.S. drone war over Yemen has been detrimental enough, both to Yemeni and to American national interests, seeing that it created more enemies than friends in the country and the region. Active intervention against the Houthis would further devastate the country and ruin any credibility left for U.S. foreign policy.

Finally, if Saudi Arabian, American and Iranian rising involvement in Yemen wasn’t enough to stir the pot, Lebanese Hezbollah and Iraqi Shia militias are also ready, willing and able to jump into the fray. The motivation is obviously there for all parties mentioned above to come to the aid of those they champion inside the country. Lacking an urgently needed diplomatic breakthrough, the worst scenarios may yet come to pass, and the Yemeni people will be the ones who suffer the most for it.

Nabeel Khoury is non-resident senior fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East at the Atlantic Council. He has contributed to the Middle East Journal, Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, International Journal of Middle East Studies, and Middle East Policy. On Twitter:@khoury_nabeel.