The Real Turning Point in Yemen Has Yet to Come

Ali Abdullah Saleh’s death could be the end of the Houthis, or a blessing in disguise. The future course of the Yemeni conflict hinges on whether and how Houthis will prevail without him.

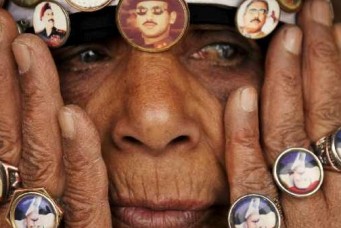

Houthi militants take part in a parade, Sanaa, Yemen, Dec. 19, 2017. Reuters/Khaled Abdullah

Yemen has seen a number of “turning points” throughout its near three-year war. Many of them, however, were not real. The death of former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh after renouncing his alliance with the Houthis in early December seemed to signal two such turning points. Unfortunately, had Saleh dissolved the alliance but remained alive, the potential for this action to notably alter the course of the conflict—and become a true turning point—would have been much higher.

Undoubtedly, Saleh was as an influential figure in Yemeni politics and it is not clear whether one of his sons will be able to sufficiently fill his shoes. For the Saudi-led coalition that has been leading a military intervention in Yemen since March 2015, his death was a major blow. It certainly saw Saleh’s break with the Houthis as a key achievement that could provide them with a viable way to exit Yemen.

It is not clear, however, whether his death was a turning point. This still largely depends on Saleh’s former allies—the Houthis—and how they perceive their strategic and tactical position. On the one hand, the collapse of the alliance impacted Houthi military capabilities and their upper hand position while Saleh’s assassination created an additional enemy from many of his supporters who are adhering to the alliance’s break. On the other hand, the Houthis are not without friends and they continue to receive external backing from Iran.

With Russia, one of the last diplomatic holdouts in Sanaa, recently moving its embassy from to Riyadh due to the “deteriorating security situation” and Saleh’s son promising to destroy the Houthis, the needle seems to point more toward continued conflict than finding a political solution. However, because conflicts are tricky—and Yemen’s is particularly so—it is not impossible that Saleh’s death will, in fact, be a turning point that will help lead to a resolution rather than represent just another reason for the fighting to continue. So what happens next?

The worst case scenario will be to continue pursuing the military option. This will likely result in increased violence and an intensified campaign against the Houthis instead of a politically navigated path forward.

A significant factor here will be Saleh’s successor—his exiled son, Ahmed Ali, appears to be the preferred and likely replacement for his father. His reported release from house arrest in the United Arab Emirates and recent travel to Riyadh suggests that he also has the support of the Saudi-led coalition. It is unclear, however, whether the plan is to back him militarily, utilize his position as Saleh’s replacement to pursue a political solution, or both.

Ali’s reaction to his father’s death reflects the potential for a more hardened response. He vowed to “lead the battle until the last Houthi is thrown out of Yemen,” and blamed Iran. This position echoes that of the Saudi-led coalition, which views the conflict as part of broader efforts to roll back and curtail expanding Iranian influence in the Middle East. Moreover, hidden behind President Donald Trump’s calls to the Saudi government to relieve the humanitarian crisis are indications that the new administration shares the same priority of confronting Iran and similarly sees Yemen as a key theater for doing so. The United States has also joined the Saudis in criticizing Tehran’s support for the Houthis—the Saudi coalition, for example, described the November 4 intercepted missile launch on Riyadh as an “act of war” by Iran while the U.S. Envoy to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, called for Tehran to be held accountable for providing missiles and related know-how to Houthis. Such rhetoric can be used to justify continued conflict.

The possibility of going down this path will increase if the disintegration of the Saleh-Houthi alliance causes the latter to turn further toward Iran as its only remaining ally. Although the group cannot (yet) be considered an Iranian proxy, increased reliance on Tehran could push them closer to this role and, more importantly, contribute to this perception, regardless of its accuracy. As a result, in contrast to the initial hope that Saleh’s abandonment of the Houthis would lead to a solution, his death may simply serve as another reason to continue to militarily address Iranian expansionism by allowing Yemen to remain a theater of conflict for regional rivals.

Houthi capabilities also should not be underestimated: the near three-year conflict demonstrates the group’s staying power despite their numbers and less advanced technology. Russia’s diplomatic withdrawal from Sanaa would also suggest that outside parties see a rise in violence as the likely outcome of recent events.

This is not, however, the only reason why continued conflict is plausible. Reports suggest the Houthis are attempting to re-establish an alliance with Saleh’s party, the General People’s Congress (GPC). This could fracture GPC forces and, if successful, limit Houthi losses in terms of manpower and allies, while also diminishing the strength of any pro-Saudi GPC force headed by Ali. Reported deaths and arrests by Houthis of high-ranking pro-Saleh figures also means the thinning out of GPC leadership, which may represent a Houthi attempt to demonstrate strength in the face of its former ally’s perceived weakness and perhaps even forcibly re-unite the alliance.

But if Houthis fail to salvage their alliance with the GPC and perceive solely Iranian support as insufficient, the best case scenario for them would be to use short-term military successes—the recapture of any lost territory in Sanaa, for example—as a way to improve their bargaining power before agreeing to talks.

This would be key since any plausible political solution is likely to severely undercut their current standing. Their small numbers (while estimates put Zaydi Shia at approximately 25–35 percent of the population, Houthis are only a subset of this group) wouldn’t, for example, justify the large territorial gains or government control they presently enjoy. In other words, while certainly the best case scenario for the Saudi-led coalition and for the Yemeni people, Houthis may not perceive a negotiated resolution as in their own best interests. In addition to historic allegations of being sidelined and discriminated against, they have also on multiple occasions rejected UN Security Council Resolution 2216, which calls for, among other things, Houthi withdrawal from territories they took over.

Even if the Houthis, the internationally recognized Yemeni government, and the Saudi-led coalition all agreed to come to the negotiating table, this would be just a first step with no guarantee of any success, to which the multiple past failed negotiations and ceasefires can attest. Here, too, the extent of Houthi reliance on Iran will come into play, with Yemeni Prime Minister Ahmed Bin Daghr claiming that “Iranian consent” would be necessary to achieve a lasting political solution and Tehran celebrating Saleh’s death as a sign that the Houthis “will ultimately emerge victorious”.

With each side needing a “win,” the biggest loser will continue to be the Yemeni population and the biggest victor Tehran, which at a limited cost has managed to bog down its regional rival in a long and costly conflict where true turning points are few and far between. For the tide to truly turn in the direction of a resolution, one or both parties will need to perceive a military option as no longer viable or even preferable. Whether this will come from broken alliances, increased international pressure, or weariness from a seemingly never-ending war is much less clear.

Miriam Eps heads the global team of analysts at Le Beck International, a Gulf-based security and risk management advisory company. On Twitter: @Miriam411.

Kierat Ranautta-Sambhi is a regional security analyst intern, also at Le Beck International.