Transitional Justice Elusive in Egypt

Only under a system of accountability, efficiency, and equality will Egypt be able to move forward with its transition. But the demands for transitional justice have consistently been framed in very broad terms, without a clear detailed vision of how they would be applied in Egypt’s specific situation.

Legal experts and casual observers in Egypt were stunned on November 27 when a misdemeanor court in Alexandria found 21 young Egyptian women guilty and sentenced fourteen of them to eleven years in jail. The remaining seven girls (all minors) are to be held in a juvenile correctional facility until further notice. The young women’s crime was gathering in an early morning protest movement, called “7am,” against the overthrow of former president Mohamed Morsi; they were arrested on October 31 on four different charges, including illegal assembly, obstructing roads, and the destruction of public property. The reaction to the ruling exposed Egyptians’ distrust of their judicial system—particularly in light of the judiciary’s perceived political role after the removal of president Morsi. The trial and ruling demonstrate the dire need for a viable transitional justice in Egypt.

The trial triggered condemnations from many prominent figures, such as the left-wing former presidential candidate Hamdeen Sabahi, who called for a presidential pardon. The interim president’s aides have responded with official statements saying that the president would exercise his power to grant amnesty, but that he was legally unable to do so until the judicial ruling becomes final.

Editor’s Note: On December 7, following an international uproar, Alexandria’s Court of Appeals overturned the Misdemeanors Court’s ruling against the 21 demonstrators. Fourteen of the women were sentenced with one year of imprisonment; the seven other defendants, who were under the age of 18, were acquitted.

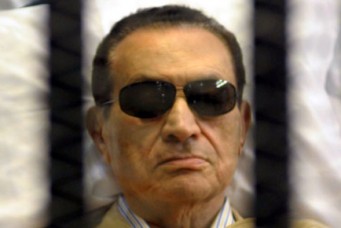

Much of the reason for the public outrage is the harsh sentences for 21 young women on relatively inconsequential charges—which particularly contrast with the light sentences and acquittals of former Mubarak officials and police officers tried for killing demonstrators over the past two and a half years. Those that were found guilty received very little jail time—most infamously, the police officer known as the “eye sniper,” who targeted protesters’ eyes with birdshot, will serve only three years in prison.

The ruling provides an ideal opportunity to think through the transitional justice system needed for Egypt. Since the overthrow of former president Hosni Mubarak’s regime in February 2011, the popular demand for a transitional justice system has been constant. However, the three subsequent regimes (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces led by General Tantawi, then the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohammed Morsi, and finally the regime in power since July 3) have failed to respond. Virtually the only progress has been the appointment of a minister of transitional justice under the current government, but this new position so far has nothing but a title. Furthermore, Article 241 in the draft constitution, completed on December 3, requires the next parliament to pass a transitional justice law. The very fact that the constitution would only now necessitate a transitional justice law illustrates how poorly the successive governments have performed in tackling the issue of transitional justice—whether intentionally or not—because Egypt nearly three years after the January 25 Revolution is still waiting for its grievances to be resolved adequately.

The demands for transitional justice have consistently been framed in very broad terms, without a clear detailed vision of how they would be applied in Egypt’s specific situation. Transitional justice, after all, is not a unified model, and any proposed vision of transitional justice, especially as concerns the trials, needs to start with the creation of a transitional justice supreme commission that has total financial and administrative autonomy and has authority over all matters related to transitional justice. The function of this commission would be to work on the judicial and non-judicial procedures relating to revealing, documenting, and prosecuting crimes and human rights violations committed in Egypt from 1981 (when the Mubarak regime came to power) to the present, in order to right the wrongs done to victims. It would also reform government institutions, build up trust in them, and lay the groundwork for national reconciliation.

There are several mechanisms through which the aforementioned goals could be achieved, including for instance establishing sub-committees with full authority to work on various aspects of the commission’s function—such committees could be formed to document violations, discuss accountability and amnesty, etc. The most crucial component of a Transitional Justice Commission, however, would be a court with sweeping powers to ensure that the trials proceed quickly, efficiently, and with judicial autonomy from both the executive branch and the normal judicial system, given the latter’s serious shortcomings in effectiveness. The power to investigate violations and crimes would be granted to judges who are answerable to the Transitional Justice Courts, avoiding the public prosecutor as part of the normal judiciary.

The hoped-for democratization and progress in social and economic development in Egypt will not happen until the grievances of the recent past and present are resolved for good. Only under a system of accountability, efficiency, and equality will Egypt be able to move forward with its transition.

This article is reprinted with permission from Sada. It can be accessed online at:http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/2013/12/06/transitional-justice-elusive-in-egypt/gvhy

Yussef Auf is an Egyptian judge and a non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Middle East Center. This article was translated from Arabic.